Many children and adolescents with mental health problems do not seek psychiatric services (

1), and 40 to 75 percent of those who do seek treatment drop out prematurely (

2,

3). Because missed appointments and dropout from treatment create serious problems for both patients and clinics, many attempts have been made to identify factors that predict treatment engagement and follow-through. Some studies have identified characteristics of the child or of the disorder (

4,

5). Others have suggested that family variables, such as poverty, parents' attitudes, and single parenthood, have a role (

1,

2). Some research has identified system factors that influence follow-through, such as the location of the treatment site, appointment delays, and whether reminders are issued (

6,

7,

8).

In a previous study, we examined factors that predicted adults' return for mental health treatment after an initial assessment (

9). The overall rate of return among adults was low: only 46 percent returned for any treatment after their assessment appointment. Being offered a prompt appointment, having more severe illness, having had previous treatment, and being unemployed each predicted return for at least one visit after the initial assessment. In the study reported here, we examined whether similar factors predicted return for treatment among children who presented at the children's mental health treatment clinic in the same community mental health system.

Methods

The charts of all children who were interviewed between August 1995 and July 1996 and whose parents consented to their inclusion in the study were reviewed. The procedures used were similar to those described in a previous report (

9). The setting was a community mental health system in Beaver County, Pennsylvania, a rural county near Pittsburgh. The children were assessed, given diagnoses, and referred for treatment by an experienced clinician using a

DSM diagnostic interview, which is the system's standard procedure. A standard chart review form was developed, and charts for 113 children were reviewed by experienced clinicians who were members of the research team and were not associated with the Beaver County Base Service Unit.

Variables reviewed included demographic information, treatment history, clinical diagnoses, severity of illness, dates of patient contacts, and referral source. We focused on the promptness of treatment (time between the assessment appointment and the first treatment appointment), severity of illness as assessed by the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scale, whether the child had had previous treatment, and the mother's employment status. Possible scores on the GAF range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better functioning. A randomly selected subset of 12 charts was reviewed by a second rater to ensure reliability of the data collection; the overall agreement rate was 99.3 percent. The University of Pittsburgh's institutional review board approved all procedures.

Results

The children in this study were significantly more likely than the adults in our previous study (

9) to return for at least one visit. Of the 113 children, 72 (64 percent) returned for at least one visit. Of 112 adults who presented for care in the adult mental health clinic in the same system, 51 (46 percent) returned for at least one visit (χ

2=7.46, df=1, p<.01).

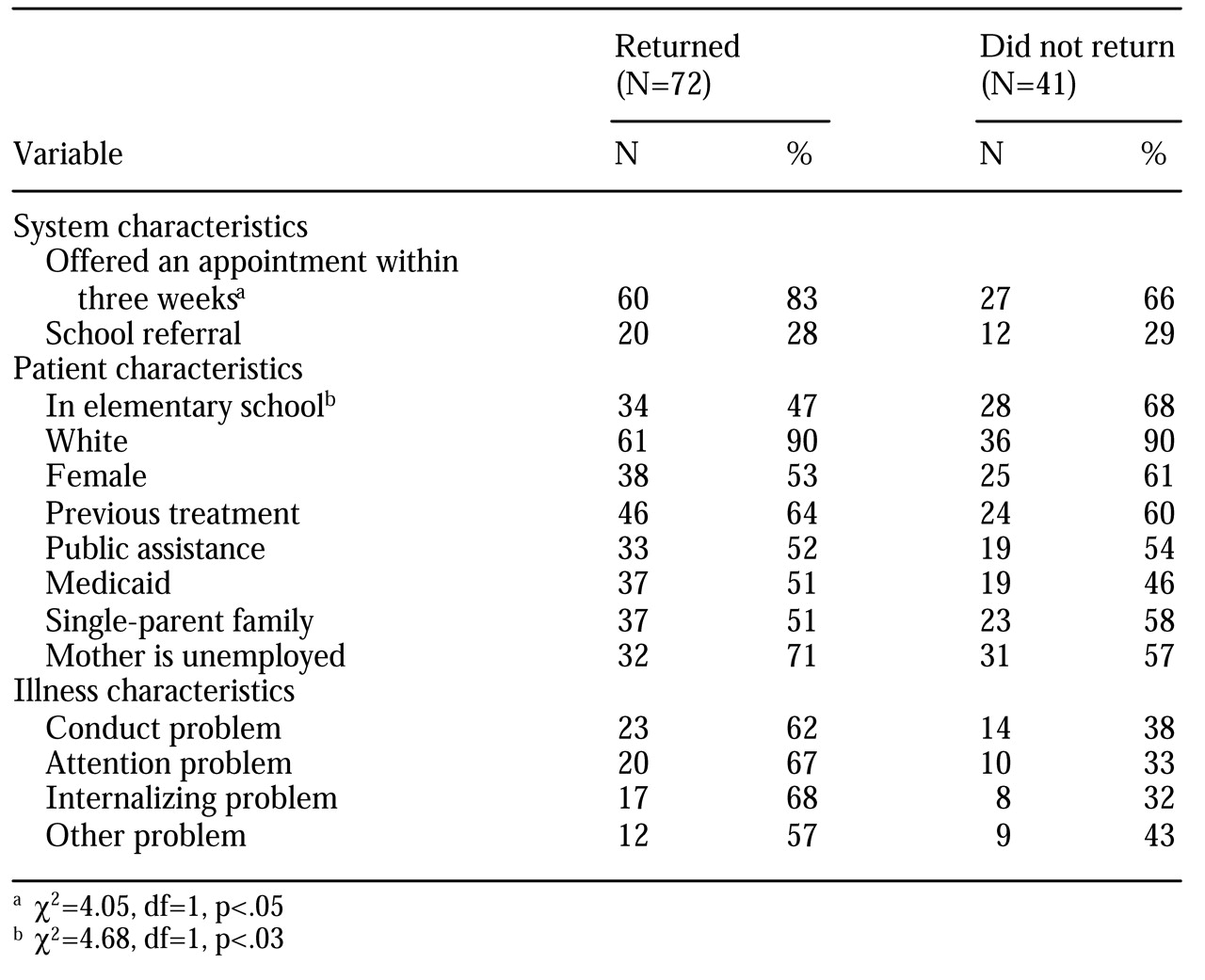

Subsequent analyses focused on factors predicting children's return. We were especially interested in whether characteristics we found to be associated with failure to return among adults would also predict failure to return among children. The comparisons between children who returned for treatment and those who did not are summarized in

Table 1. As the table shows, few of the characteristics predicted whether children would return for treatment.

Exploratory analyses of the effects of delays in the availability of appointments suggested that the likelihood of children's return declined steeply if delays were three weeks or longer. Of 87 children who were offered appointments within three weeks, 60 (69 percent) returned for treatment, whereas only 12 (46 percent) of 26 children who were offered appointments more than three weeks later returned for treatment (χ2=4.05, df=1, p<.05). Thus, similar to our findings with adults, the promptness of scheduled appointments was important. However, a longer delay was tolerated for children than for adults.

Of the demographic characteristics we examined, only the age of the child predicted return for treatment—older children were more likely to return for at least one visit. Thirty-eight (75 percent) of 51 children in the sixth grade or above returned for treatment, compared with only 34 (55 percent) of 62 children who were in the fifth grade or below (χ2=4.68, df=1, p<.03). Unlike the finding for adults, previous treatment did not predict return. Of 70 children who entered treatment, 47 (67 percent) had previously received treatment. Of 40 children who did not return for treatment, 24 (60 percent) had previously received treatment.

Among adults, those who were unemployed were marginally more likely to return for treatment. However, we found that the mother's employment status did not predict whether a child returned for treatment. Among the 45 mothers who were employed, 32 (71 percent) had children who returned for treatment; of the 54 mothers who were not employed, 31 (57 percent) had children who returned.

Also in contrast with adults, GAF scores at the time of presentation did not help in predicting whether children would return. For the children who returned for treatment, the mean± SD GAF score was 46.2±10.3, and for those who did not return, it was 47.5±10.2; the difference was not significant. Similarly, type of diagnosis did not predict which children would return for at least one treatment visit.

Discussion and conclusions

Although this study had some limitations, including our use of a convenience sample and the large number of tests conducted on the data, we found that children were much more likely than adults to return for mental health treatment after an initial assessment appointment in this rural community mental health system. We also found that some factors that appeared to be obstacles to return for treatment among adults did not affect the likelihood of return among children.

A fundamental difference between adults and children who seek mental health care is that children's visits are usually supported by an adult who brings the child to the appointment. It appears that adults may be more likely to tolerate inconvenience and delay when seeking treatment for children in their care than when seeking treatment for themselves. The results of other ongoing studies we are conducting suggest that women who bring their children for care are likely to have undiagnosed mood and anxiety disorders themselves but are unlikely to follow up on mental health referrals to address these problems. Initial interviews with the women in our study supported our impression that they considered their children's mental health needs to be more pressing than their own.

As others have found (

6,

7), the promptness of scheduled appointments predicted return for treatment among children. The rate of return for at least one visit appeared to drop off when the first appointment was more than three weeks after the assessment date. This finding contrasts with adult return rates, which drop off if the first appointment is more than a week after the assessment date. These results clearly highlight the problem for treatment follow-through created by appointment waiting lists. Managed care programs have stated their intention to establish standards that limit the time to the first appointment. However, progress in this area is currently unknown, and time to appointments has been reported as a source of consumer dissatisfaction in some managed care agencies (

10).

The child's age predicted return in our study. Armbruster and Fallon (

2) found that children under five years of age were more likely not to show up for a first appointment. Similarly, we found that younger children were more likely not to return for initial treatment. Children of middle- and high-school age were more likely to return for treatment, possibly because parents may take a child's behavioral problems more seriously as the child gets older, especially if schools are less tolerant of such problems.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant R24-MH-56848 to Dr. Shear, grant R24-MH-056848 to Dr. Anderson, and grant K01-MH-0189 to Dr. Greeno by the National Institutes of Health.