The National Institute of Mental Health estimates that there are between eight and 25 suicide attempts for every completed suicide. The U.S. suicide rate, which remained relatively stable between 1950 and 1990, declined during the past decade. However, it is troubling that there are no national measures of the corollary rate of suicide attempts. Using emergency department admissions for self-inflicted injuries as a partial proxy for suicide attempts, we analyzed data from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS) from 1992 through 1999 (

1). Data on the U.S. suicide rate were obtained from the

National Vital Statistics Reports (

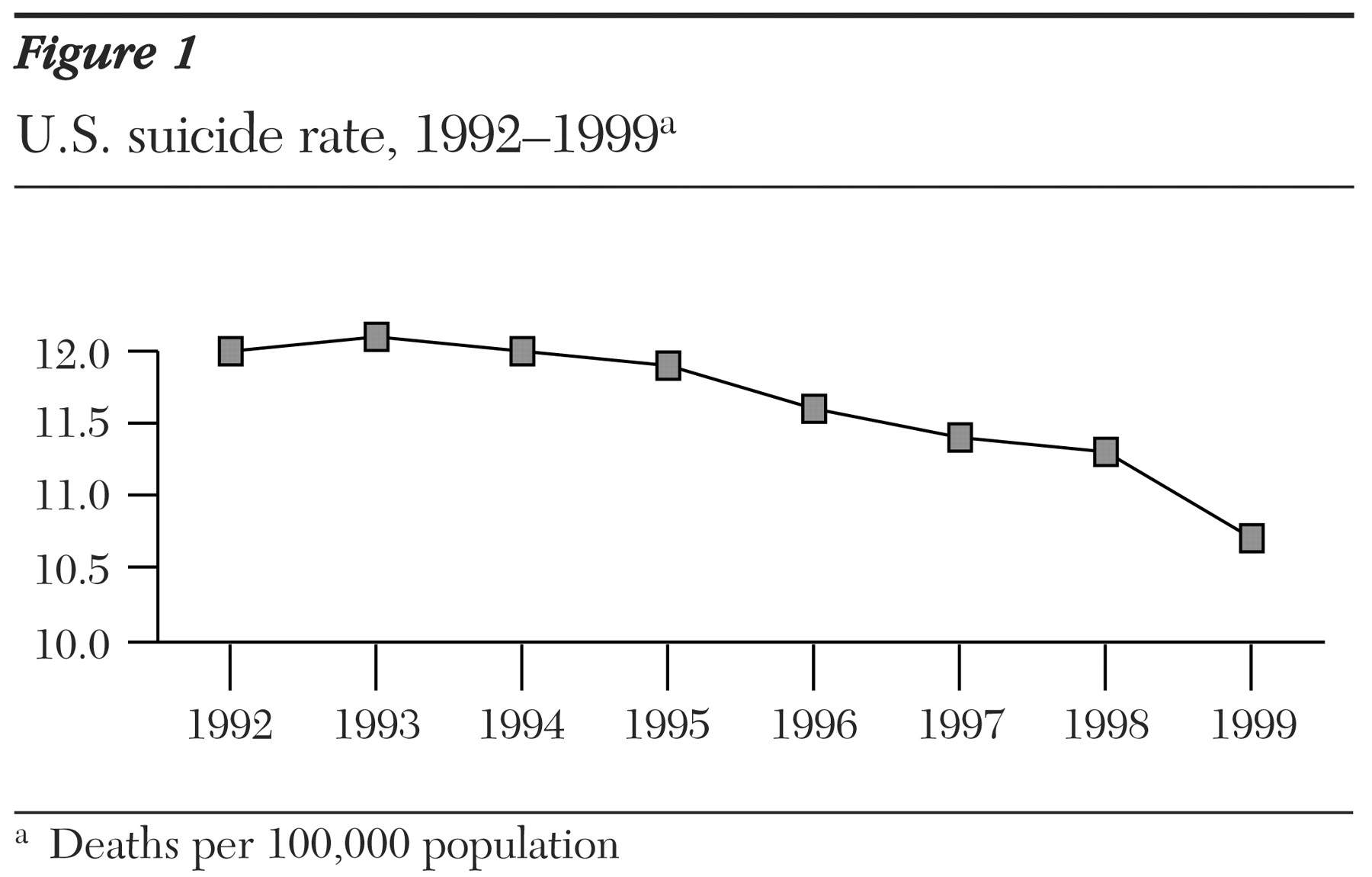

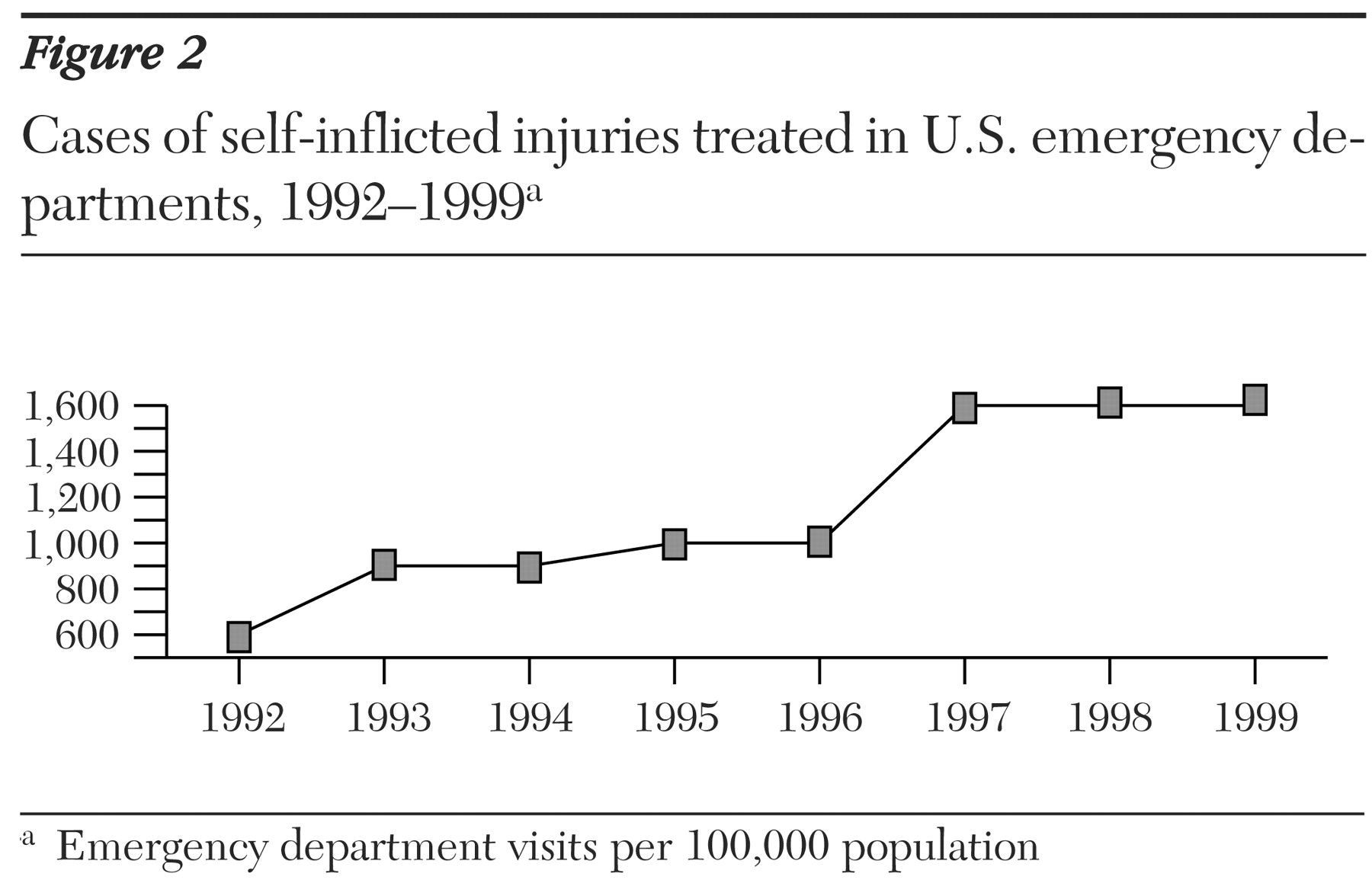

2). Trend data for both these measures are plotted in

Figure 1. Between 1992 and 1999, the number of visits to emergency departments for intentional self-inflicted injuries per 100,000 persons per year more than doubled, from 600 to 1,600 (

3). In contrast, over the same period the suicide rate per 100,000 persons per year dropped slightly, from 12 to 10.7. Thus, trends in the U.S. suicide rate and emergency department admissions for self-inflicted injuries have been moving in opposite directions since 1992.

The question remains whether emergency department admissions for self-inflicted injuries are a reasonable proxy for suicide attempts. In July 2000 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) collaborated with the Consumer Product Safety Commission's National Electronic Injury Surveillance System to create a database that included all types and causes of nonfatal injuries treated in U.S. hospital emergency departments (

4). The CDC analysis indicated that 60 percent of self-inflicted injuries were considered probable suicide attempts, and 10 percent were considered possible attempts; in the remaining 30 percent of cases, information about the patient's intent was unclear or not recorded. Thus it appears that a majority of individuals with self-inflicted injuries who were seen in emergency departments had made a suicide attempt.

The increasing number of emergency department admissions for self-inflicted injuries in the U.S. may reflect an increase in actual suicide attempts. Alternatively, it may be attributable to greater access to care, decreasing stigma about mental illness, and increased awareness among emergency department clinicians of suicidal risk behaviors.

Explanations for the divergence of rates may include the reduced lethality of suicide methods—for example, tricyclic antidepressants are now less frequently prescribed—and the improved quality of emergency response services and emergency care.