Smoking and hazardous alcohol use are common among primary care populations and result in preventable morbidity, mortality, and loss of quality of life. Because brief interventions can reduce tobacco use (

1,

2) and hazardous drinking (

3,

4), routine screening and subsequent counseling for smoking and hazardous or problem alcohol use are recommended (

5,

6). Some agencies also support screening and intervention for other drug abuse in primary care (

7,

8). However, women may be less likely than men to receive substance use counseling from their primary care physicians (

9,

10).

Little is known about the prevalence of substance abuse among women patients in the Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system, although rates of substance abuse among non-VA women patient populations are generally higher than among women in the general population (

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17). Two studies of women VA patients reported higher rates of smoking than among women in general populations and women who were not veterans (

18,

19). The published studies of screening prevalence rates of problem drinking among women VA patients either have used screening tests known to be relatively insensitive in relation to women (

20,

21) or have not used the standard scoring for the TWEAK (

22).

A better understanding of the prevalence of substance abuse among women seeking care at VA medical centers and the identification of subgroups of this population at high risk for substance abuse will aid in the development and implementation of effective screening and intervention programs. This report describes the prevalence of past-year substance abuse (cigarette smoking, hazardous and problem drinking, and other drug abuse) as measured by brief, gender-appropriate screening instruments in a sample of women VA patients. Rates of substance abuse in subgroups based on age and on psychiatric screening tests are also presented.

Methods

Participants and setting

In 1998, VA Puget Sound Health Care System women's health research surveys were mailed to women who had received health care from the system between October 1, 1996, and January 1, 1998, and had a known address within the Puget Sound area. Women who had inaccurate addresses or were severely disabled were not eligible. The 16-page survey included items assessing health history and behaviors, history of preventive screening, mental health, and patient satisfaction. This report is based on cross-sectional analyses of the responses. The University of Washington institutional review board approved this project, and a cover letter with the survey stated that completion of the survey was an indication of consent to participate.

Measures

Demographic characteristics. Survey responses were not anonymous. Demographic data for respondents and nonrespondents were extracted from VA administrative databases, except age and highest educational level, both obtained from the survey.

Substance abuse. The comprehensive category of substance abuse refers here to use of a substance that may place a person at risk for negative consequences. Criteria for hazardous and problem drinking are included below. Any cigarette smoking or drug use was considered hazardous and therefore abuse.

Cigarette smoking. Survey respondents described their cigarette smoking status as "never," "current smoker," or "past smoker—quit." Smokers who reported quitting within the past year and current smokers were considered past-year smokers.

Hazardous drinking. The first three questions from the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) (

23) were used to measure past-year consumption levels. The AUDIT's first two questions were followed by a gender-specific version of the third question, asking "How often in the past year have you had four or more drinks on one occasion?" The gender-specific component is the use of four or more drinks as the criterion for binge drinking (

24,

25,

26,

27). A report of having four or more drinks on one occasion or seven or more drinks per week (standard AUDIT response options) was considered past-year hazardous alcohol use (

28).

Problem drinking. Women who reported any past-year drinking and screened positive on the five-item TWEAK screening questionnaire (

29) were considered to be problem drinkers.

The TWEAK questionnaire was included because of its higher sensitivity in identifying problem drinking among women (

21). The "high" version of the tolerance question was used: "How many drinks does it take before you begin to feel the first effects of alcohol?" The standard tolerance threshold of three or more drinks was used (

30). Any response but "never" was considered a positive response for the remaining four TWEAK questions. We used standard TWEAK scoring for a total possible score of 7 points. A positive screen was defined as a TWEAK score of 2 or more (

29).

Other drug abuse. The Two-Item Conjoint Screening questionnaire (

31), a validated screening test for current drug and alcohol abuse with a sensitivity of 76.4 percent for women (

32), was modified to ask only about drug abuse, because we already had validated screening measures for alcohol use. For either question, a response of "Yes, during the past year" was considered positive (

32). Information about specific substances used was not collected.

Mental health symptoms. The validated Patient Health Questionnaire (

33) was used to screen for current major depression, panic disorder, and eating disorders. Symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) were assessed with the PTSD Checklist (

34), which assesses symptoms of PTSD but does not assess specific trauma exposure. A PTSD Checklist cutoff score of 38 indicated a positive screen for PTSD, because this scoring threshold performed optimally in our interview validation study in a female VA population (

35).

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used for demographic and clinical characteristics and for screening prevalence rates. Chi square and t test analyses were used to compare survey respondents with eligible nonrespondents to assess response bias. Bivariate logistic regression was used to estimate the age-adjusted odds of screening positive for each category of hazardous substance use (smoking, hazardous drinking, problem drinking, and other drug abuse) given a positive screening test for any psychiatric condition. All analyses were conducted with SPSS for Windows (

36).

Results

Of the 1,935 eligible women veterans, 1,257 (65 percent) returned surveys with complete substance use data.

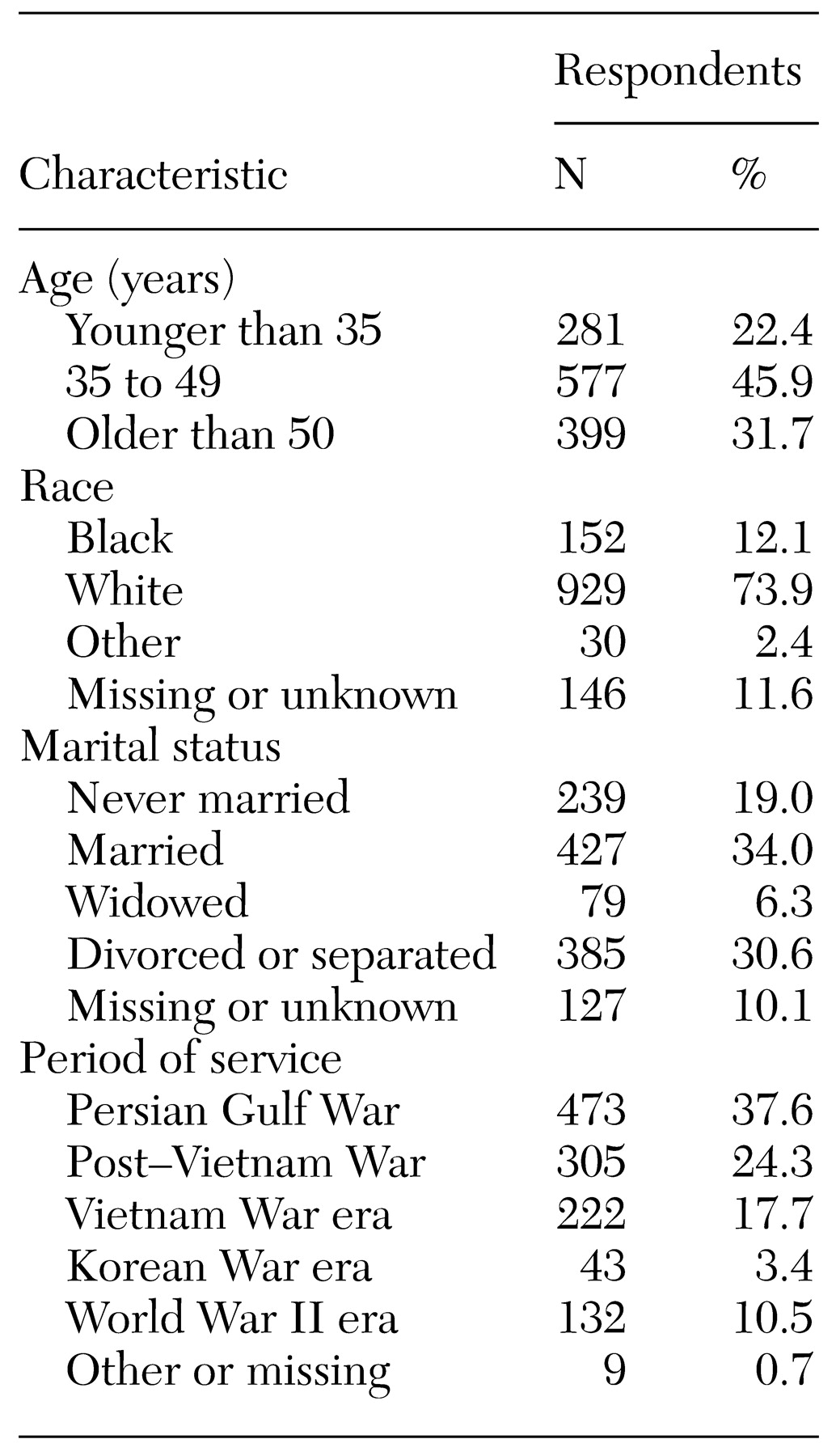

Table 1 shows demographic information; the majority reported at least some college attendance (N=1,077; 86 percent). Compared with eligible nonrespondents, survey respondents were more likely to be white (χ

2=10.23, df=3, p=.017 ) and at least 50 years old (χ

2=15.24, df=2, p=.002). No significant group differences were observed for marital status or period of military service.

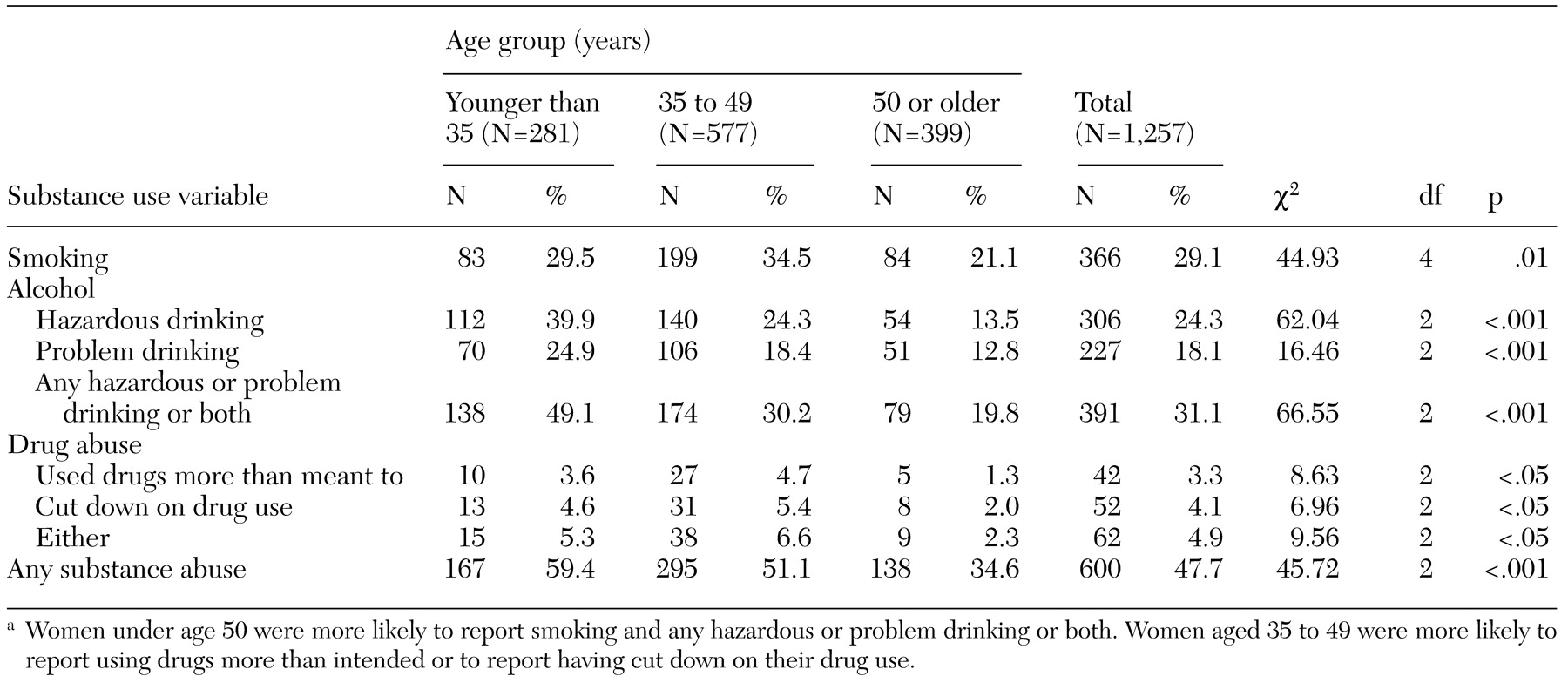

Of the respondents, 600 (almost 48 percent) screened positive for at least one type of substance abuse, as shown in

Table 2. Whereas 305 (99.7 percent) of the hazardous drinkers reported drinking four or more drinks on one occasion (binge drinking), only 50 (16.7 percent) reported drinking seven or more drinks a week, and all but one of the 50 also reported binge drinking.

Women who reported smoking (N=366) were at increased risk for hazardous drinking, problem drinking, or both (N=185, or 50.5 percent of reported smokers) compared with reported nonsmokers (N=862) at risk for these types of drinking (N=235, or 27.3 percent of reported nonsmokers; χ2=63.10, df=2, p<.001).

Conversely, women who reported any drinking (N=782) were at increased risk of smoking (N=257, or 32.9 percent of reported drinkers) compared with reported nondrinkers (N=458) at risk of smoking (N=107, or 23.4 percent of nondrinkers; χ2=312.30, df=4, p<.001).

Women who reported any drinking (N=782) were also more likely to screen positive for other drug abuse (N=50, or 6.4 percent of reported drinkers) than were reported nondrinkers (N=11, or 2.4 percent of reported nondrinkers; χ2=9.85, df=2, p=.007). Of the 600 women who screened positive for any substance abuse, 408 (68 percent) screened positive for only one substance area the three assessed (smoking, alcohol use, and drug use), 165 (27 percent) screened positive for two substance areas, and 27 (4.5 percent) screened positive for abuse in all three substance areas.

In general, women under age 50 years had significantly higher rates of smoking, hazardous or problem drinking and other drug abuse than did women 50 and older (

Table 2). Women aged 35 to 49 years were significantly more likely than other women to report using drugs more than intended in the past year or to report having cut down on their drug use in the past year.

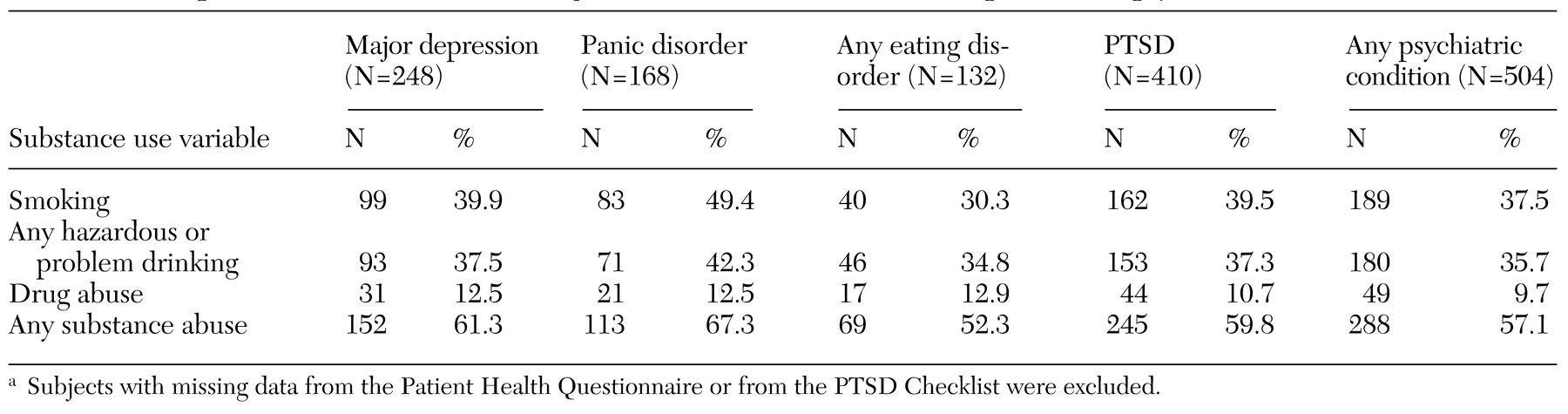

As shown in

Table 3, a total of 504 respondents (40.1 percent) screened positive for any psychiatric condition (major depression, panic disorder, any eating disorder, or PTSD), and these women had higher rates of substance abuse than did those who screened negative.

Age-adjusted logistic regression suggested that women who screened positive for any psychiatric condition had increased odds of past-year smoking (odds ratio [OR]=1.79; 95 percent confidence interval [CI]= 1.39 to 2.30), problem drinking (OR=1.36; CI=1.01 to 1.82), and other drug abuse (OR=5.63; CI=3.01 to 10.53) but did not have increased odds of past-year hazardous drinking.

As shown in

Table 3, of the patients who screened positive for any psychiatric condition (N=588), 288 (57.1 percent) also screened positive for any substance abuse. The screening prevalence rate for any psychiatric condition increased from 33 percent among women without substance abuse to 44 percent among those with one substance of abuse and to 57 percent in those with multiple substances of abuse (χ

2=44.68, df=3, p<.001).

Discussion

This study of the screening prevalence of past-year substance abuse and psychiatric comorbidity among 1,257 women VA patients found relatively high rates of smoking (29.1 percent), hazardous or problem drinking (31.1 percent), and other drug abuse (4.9 percent). Among women younger than 35 years, hazardous drinking, problem drinking, or both were more common than smoking or drug abuse, whereas among women over 35, smoking was most common. Women under 50 and women who screened positive for any psychiatric condition were at increased risk for substance abuse.

Given prevalence rates ranging from 22 percent to 28.4 percent for past-year smoking among women in the general population (

37,

38), women veterans are at comparable risk for smoking and thus for smoking-related illnesses (

19).

Screening prevalence rates for past-year hazardous drinking, problem drinking, or both were higher in this study than in previous studies of female patients, both within and outside the VA (

11,

12,

13,

15,

16,

17). The higher prevalence of such drinking in this study probably reflects several differences from previous studies of female VA patients. Primarily, previous studies have used the CAGE, the MAST, or variations of these (

11,

20) or a nonstandard scoring for the TWEAK alcohol screening questionnaire (

22). We screened for both hazardous and problem drinking and used a gender-specific screening question for binge drinking (

27) and the standard scoring on the TWEAK questionnaire (

26). We believe this study is a more accurate reflection of the prevalence of at-risk drinking among women veterans, given the low sensitivity of alcohol screening tests used in previous studies.

Almost 5 percent of participants in this study (N=62) reported past-year drug abuse, a result consistent with previous findings in other women VA patient populations (

39). Women who reported past-year drinking or screened positive for any current psychiatric condition were more likely to screen positive for drug abuse.

Of all respondents, 504 (40 percent) screened positive for at least one psychiatric condition; of these 504 respondents, 81 percent screened positive for PTSD, and 57 percent also screened positive for any substance abuse in the past year. The rate of comorbidity for substance abuse and PTSD (59.8 percent) is consistent both with previous samples of women VA patients (53.5 percent) (

40) and with nonveteran women samples (30 percent to 59 percent) (

41,

42,

43).

Some limitations of this study should be noted. Because data were based on brief, self-administered screening tests rather than diagnostic interviews and were from a sample at one VA facility, they may not be generalizable to other populations of women, veteran or nonveteran. Because respondents were older than nonrespondents, substance abuse rates may have been underestimated, given that younger women are more likely to report substance abuse. Another possible response bias is the exclusion of women who did not have a known address or who were severely disabled. If these women had higher rates of substance abuse, the prevalence rates reported here may be underestimates.

One strength of this project was that these screening tests were chosen for their suitability for women and allowed us to survey 65 percent of the eligible female population, therefore decreasing potential nonresponse bias. Furthermore, our findings are taken from a relatively large population-based survey and may be applicable to the increasing population of women treated at VA medical centers. Finally, most studies of substance abuse examined rates of smoking, drinking, or drug abuse separately; we examined rates of all three, including problem drinking, as well as their relationships to age and to screening positive for psychiatric conditions.

This study found that women VA patients, especially those under age 50 and those who screen positive for psychiatric conditions, have relatively high rates of substance abuse. The rate of concurrent substance abuse and other behavioral health conditions adds significantly to the burden of assessment and management of these conditions for clinicians in a variety of settings. Although some patients may be appropriately referred to specialized addiction treatment services, others will not be appropriate for or will not accept referral to these services. Our findings suggest a need to integrate substance abuse expertise into all levels of VA health programs for women, including both primary care and mental health clinics.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant GEN-97-022 from the health services research and development service of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Bradley is currently supported by grant K23AA00313 from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and is a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Generalist Physician Faculty Scholar.