The challenges of fostering wider use of empirically validated treatments in clinical settings revolve around a number of critical issues: generalizability (Will this treatment work with different practitioners, patients, and settings?), implementation (What kinds of training and what kinds of trainers are necessary for what kinds of clinicians to learn a new technique?), cost-effectiveness (Compared with the costs of learning and implementing this treatment, what are the savings, particularly in comparison to existing methods?), and marketing (How acceptable is a new treatment to both clinicians, patients, and payers outside research settings?)

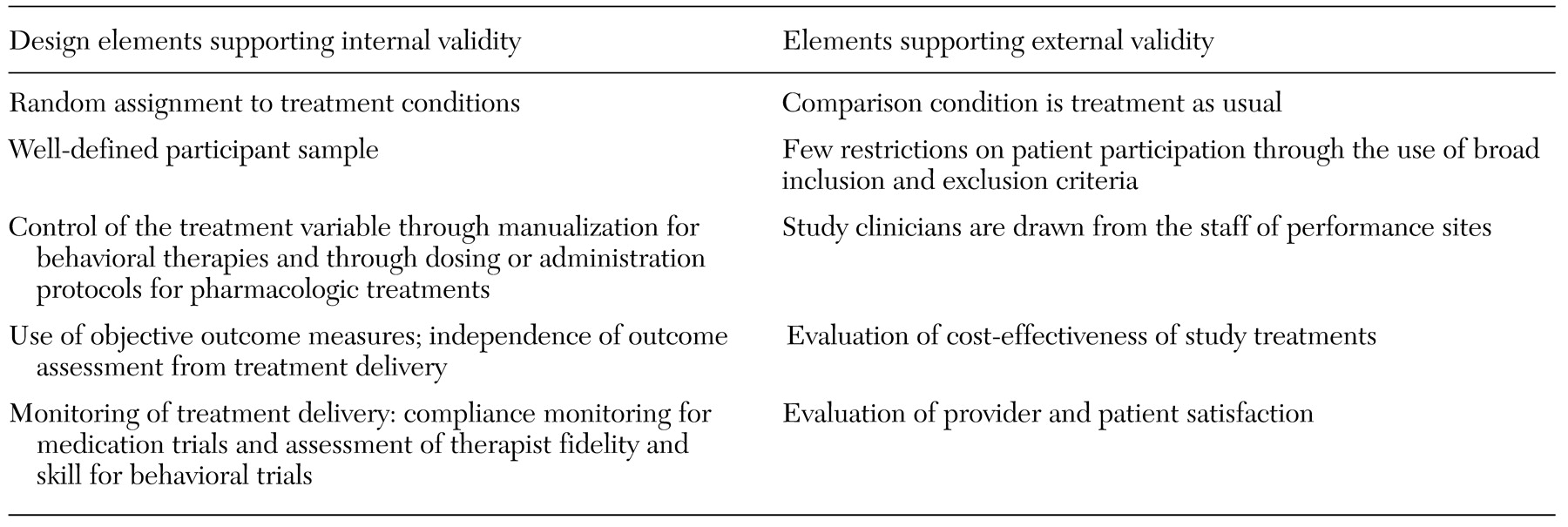

Elements of efficacy trials to be retained

In a hybrid model, it is critical that scientific rigor be preserved through the use of design features that protect crucial aspects of internal validity. These features include random assignment of patients to treatments, blind delivery of treatments, blind assessment of outcomes, intention-to-treat analyses, use of objective outcome measures, definition and monitoring of treatments delivered, specialized training of providers in delivering study treatments, and evaluation of the integrity of study treatments (for example, assessment of compliance in medication trials and evaluation of treatment fidelity in behavioral trials).

Although these features add to the cost and complexity of clinical trials, the disadvantages of omitting them are numerous and consequential. For example, lack of randomization to treatment conditions means that a study loses the ability to address fundamental questions, such as whether the experimental treatment was more effective than standard treatment and whether the level of change associated with the experimental treatment was meaningful. Most important, however, is that studies that do not randomly assign participants to a condition lose the ability to rule out numerous alternative explanations for findings, such as maturation, history, and measurement effects. Borkovec and colleagues (

47) have noted that failure to protect these vital aspects of internal validity renders generalizability issues moot.

Moreover, for most empirically validated treatments for substance abuse, only a handful of supporting clinical trials may exist. Thus, even as effectiveness studies are undertaken, it will be essential to continue to conduct randomized controlled comparisons, because there are few true reference conditions in substance abuse treatment against which to evaluate the efficacy of novel approaches. For example, in the treatment of opioid dependence, methadone maintenance most resembles a standard "reference" treatment. However, largely due to variability in the clinical context in which it is delivered, outcomes for methadone maintenance are highly variable (

11,

48).

In addition, control conditions in efficacy trials are generally designed to evaluate highly focused research questions—for example, whether a given medication is more effective than a placebo that controls for expectations of improvement or whether a given behavioral therapy is more effective than a minimal discussion condition. Thus control conditions that are typically used in efficacy research rarely resemble treatment as delivered in clinical practice and thus do not address issues of interest to clinicians and policy makers—for example, whether adding a novel treatment enhances outcomes compared with treatment as usual.

Effectiveness elements to be retained

To expand the range of issues addressed in efficacy research, we propose a hybrid model in which the above design elements are retained while additional effectiveness components are added.

Enhanced diversity in patients and settings. Few single-site trials are designed or sufficiently powered to allow meaningful analysis of sources of variability in outcome due to variables such as ethnicity, gender, severity, or psychiatric comorbidity. Diversity may be enhanced by using a number of strategies, such as conducting clinical trials in community-based programs and multiple geographic settings, using less restrictive inclusion and exclusion criteria, reducing barriers to participation (for example, not restricting protocols to English-speaking participants or not requiring participants to undergo very lengthy assessment batteries), and allowing some variation in treatment implementation across sites.

Such strategies will greatly enhance our knowledge about the robustness of various treatments. For example, it will be extremely useful to know if treatment A is effective among persons with both alcohol and cocaine abuse but not those with both depression and cocaine abuse. Similarly, it is of great importance to know whether an innovative treatment is effective when implemented by a broad range of clinicians, as opposed to just those with advanced degrees.

Enhancing diversity in study populations typically requires multiple single-site replication studies or larger multisite trials. However, Klein and Smith (

49) have noted that even community-based replications or multisite trials may have limited generalizability. That is, simply because a study is conducted in a community-based setting does not mean that its results are generalizable to all other community settings.

Attention to training issues. If clinicians are to implement empirically validated treatments, effective training is essential. Although pharmaceutical companies widely disseminate information about new pharmacologic approaches to physicians, many community-based treatment programs have no or few affiliated medical personnel to implement these treatments (

50).

Similarly, although methods for training clinicians in manual-guided therapies for clinical efficacy trials are well established (

51,

52,

53), such methods have largely been accepted on the basis of face validity (

54,

55,

56). It is not known whether standard methods of training therapists will be feasible or effective when applied to real-world clinicians. Training in clinical efficacy trials is usually geared toward highly trained and experienced clinicians. Thus trainers may assume basic familiarity with underlying principles of the treatment. However, clinicians who work in community-based drug abuse settings have varied educational backgrounds (

4). Thus standard training methods for clinical trials—which encompass brief review of a treatment manual, watching a few videotaped vignettes, and participating in a few role-playing exercises—may be insufficient for many drug abuse counselors.

If we are to learn what kind of training is needed by various types of clinicians to effectively implement scientifically validated treatments, empirical studies of training methods are needed. Focused evaluations of training methods may be integrated into large stage III hybrid studies in which, for example, the pilot or startup phase might be seen as providing a vehicle for systematically evaluating the effectiveness of various training methods with a variety of types of clinicians and settings. That is, clinicians could be randomly assigned to different training methods, such as low-intensity versus high-intensity training, and their adherence and competence in implementing treatments could be evaluated.

Evaluation of cost-effectiveness. Almost all novel therapies come with some added cost, either the cost of the treatment itself or training costs. Because the added cost of empirically validated treatments has typically not been a component of efficacy studies, researchers have had little basis on which to convince program leaders or policy makers that the efforts and costs entailed in introducing new treatments are justified.

The value of integrating cost-effectiveness analyses into clinical trials—even those that occur early during the course of a treatment's evaluation—is suggested by several recent studies that have demonstrated cost savings and benefits associated with adding enhancements to standard approaches to substance abuse treatment (

57,

58,

59,

60,

61). When cost savings for innovative treatments are demonstrated, providers and third-party payers are likely to be much more interested in supporting the adoption of these treatments into standard care.

Assessment of patient and provider satisfaction. In recent years, increasing emphasis has been placed on client preference and patient satisfaction as indicators of a treatment's utility and value (

62,

63,

64,

65). Indicators of patient satisfaction are important in determining whether a new approach would add value to a program by making it more attractive to patients. Inclusion of satisfaction measures that address patients' global judgments of satisfaction and improvement, supplemented by more specific feedback on their reactions to individual components of innovative treatments—for example, content, duration, intensity, and therapist (

66)—will be invaluable in evaluating the success of novel treatments in community settings. Greater satisfaction of clinicians with the nature of the interventions they provide to their patients may be important in reducing staff turnover in community programs, in which the rate of turnover is as high as 15 to 50 percent annually (

13,

67).