Children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) use more medical services and have associated costs that are approximately twice those of other children (

1,

2,

3,

4). Children with ADHD also have significantly more pharmacy fills and mental health and primary care visits (

3). The costs associated with ADHD are comparable to those associated with asthma (

1,

2).

Less is known about service use and costs associated with other childhood psychiatric disorders. In one study, symptoms of depression and substance abuse were associated with an increase in the average number of pediatric outpatient visits among adolescents (

5). Guevara and colleagues (

3) reported that children with ADHD and a coexisting psychiatric disorder incurred substantially higher costs than those with ADHD alone, but the impact of other psychiatric disorders per se was not examined. Although some studies have found that children with ADHD use more mental health and social services than other children (

6), this may not be true of all children with psychiatric disorders (

7).

The aim of this study was to determine which psychiatric disorders of childhood are associated with greater service use and costs. Medicaid data were used to compare service use and expenditures between youths with various psychiatric diagnoses and those without a diagnosis.

Methods

The sample comprised all 76,662 children between the ages of three and 15 years on July 1, 1994, who received Medicaid-reimbursed physician or psychiatric services from fiscal years 1993 through 1996 in Philadelphia. Demographic characteristics were obtained from the Medicaid files. Service use and expenditure data were derived from Medicaid paid claims. Data were not available for some diagnostic procedures. Because no copayment is associated with Medicaid, reimbursements accurately reflect expenditures. Expenditures were aggregated over the three-year period.

Diagnoses were assigned if two or more claims were associated with that

ICD-9 code over the course of the study. Diagnostic codes were truncated at three digits because of concerns about reliability. Diagnostic categories were limited to the five most prevalent in the sample: 309 (adjustment disorder), 314 (attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder), 313 (oppositional defiant disorder), 312 (conduct disorder), and a combination of codes 296 (major depressive disorder) and 311 (depression not otherwise specified), for which previous research has shown poor discriminant validity among children and few differential consequences (

8), including service use (

9). These categories included 94 percent of all children with a psychiatric diagnosis.

Chronic physical conditions, identified from the literature (

10), were assigned if an individual had two or more claims for diabetes, sickle cell anemia, cerebral palsy, seizures, trisomy, cancer, immunocompromised status, autoimmune disease, major organ disease, mental retardation, congenital anomaly, asthma, or congenital heart disease. Time on welfare was measured by using welfare eligibility files.

Three analytic strategies, discussed elsewhere (

11), were used. We used linear regression, because the arithmetic—as opposed to the geometric—mean is a more accurate measure of system expenditures. The large sample also made the analyses relatively robust to violations of normality.

Additional analyses were conducted with a two-step log transformation of expenditures. The resulting geometric mean may not be as useful for system planning in that the geometric mean multiplied by the number of children usually underestimates system expenditures. However, it normalizes the data, reduces the effect of outliers, and provides an opportunity for comparison with other studies (

3,

4). The median total expenditures associated with each psychiatric diagnosis were calculated to provide an estimate that reduces the influence of outliers and allows for comparison with other studies (

1,

4).

Adjusted arithmetic and geometric mean expenditures for total and ambulatory care were estimated by using linear regression. The odds of hospitalization and emergency department use were estimated by using binary logistic regression. Linear regression was then used to estimate arithmetic and geometric mean expenditures among children who used that particular service. The odds of mental health service use were calculated for children who had received any psychiatric diagnosis. Adjusted mean expenditures were then calculated for those who had used mental health services. Median expenditures were also calculated for each service category.

Results

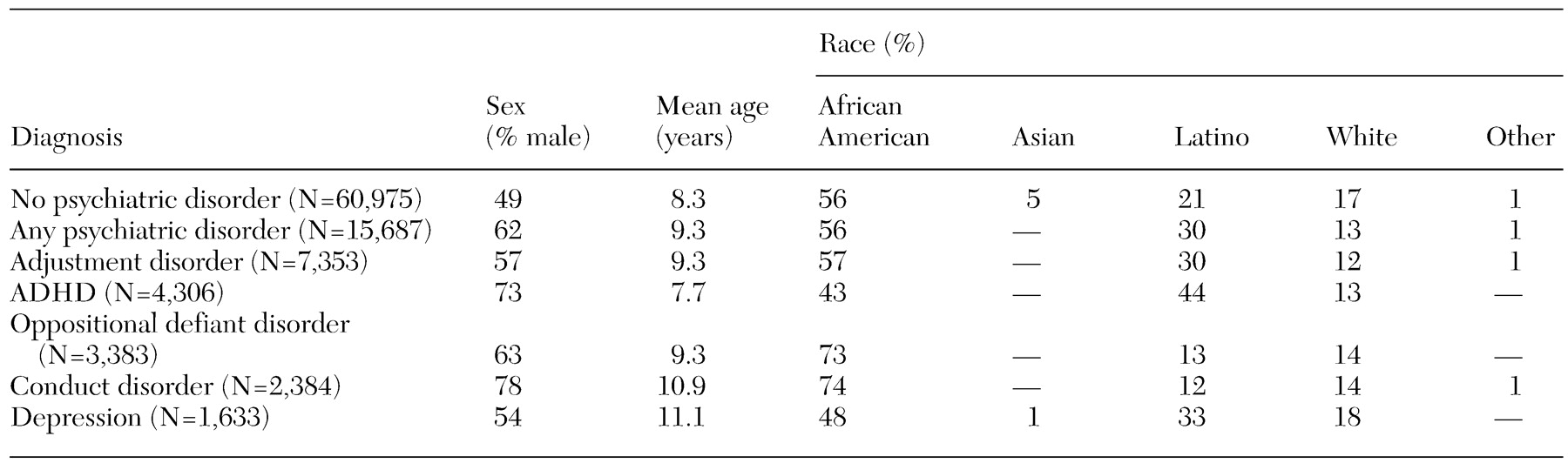

Boys constituted approximately half of the sample. The average age of the children was 8.5 years. A little over 55 percent of the sample was African American, 23.2 percent was Latino, 16.8 percent was white, 3.8 percent was Asian, and 1 percent was "other." The children were welfare recipients for an average of 31.5 of 36 months. Of the children in the sample, 20.5 percent had a psychiatric diagnosis (ICD-9 codes 290 to 319). Adjustment disorder was the most common diagnosis (9.6 percent), followed by ADHD (5.6 percent), oppositional defiant disorder (4.4 percent), conduct disorder (3.1 percent), and depression (2.1 percent).

Characteristics of the sample by diagnosis are summarized in

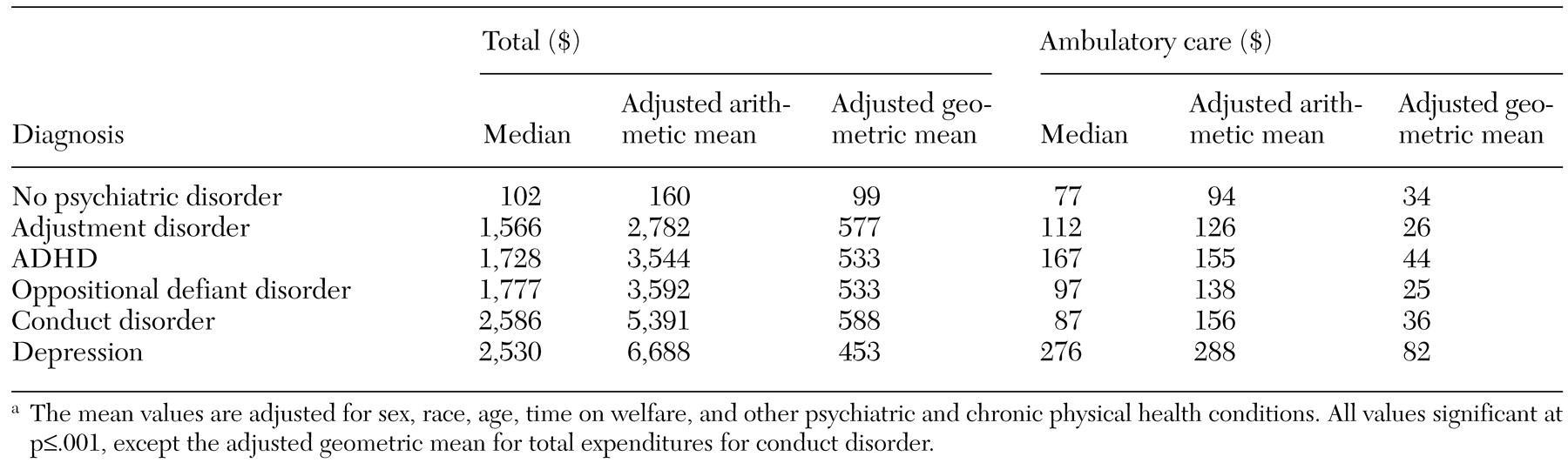

Table 1, adjusted total and ambulatory care expenditures are presented in

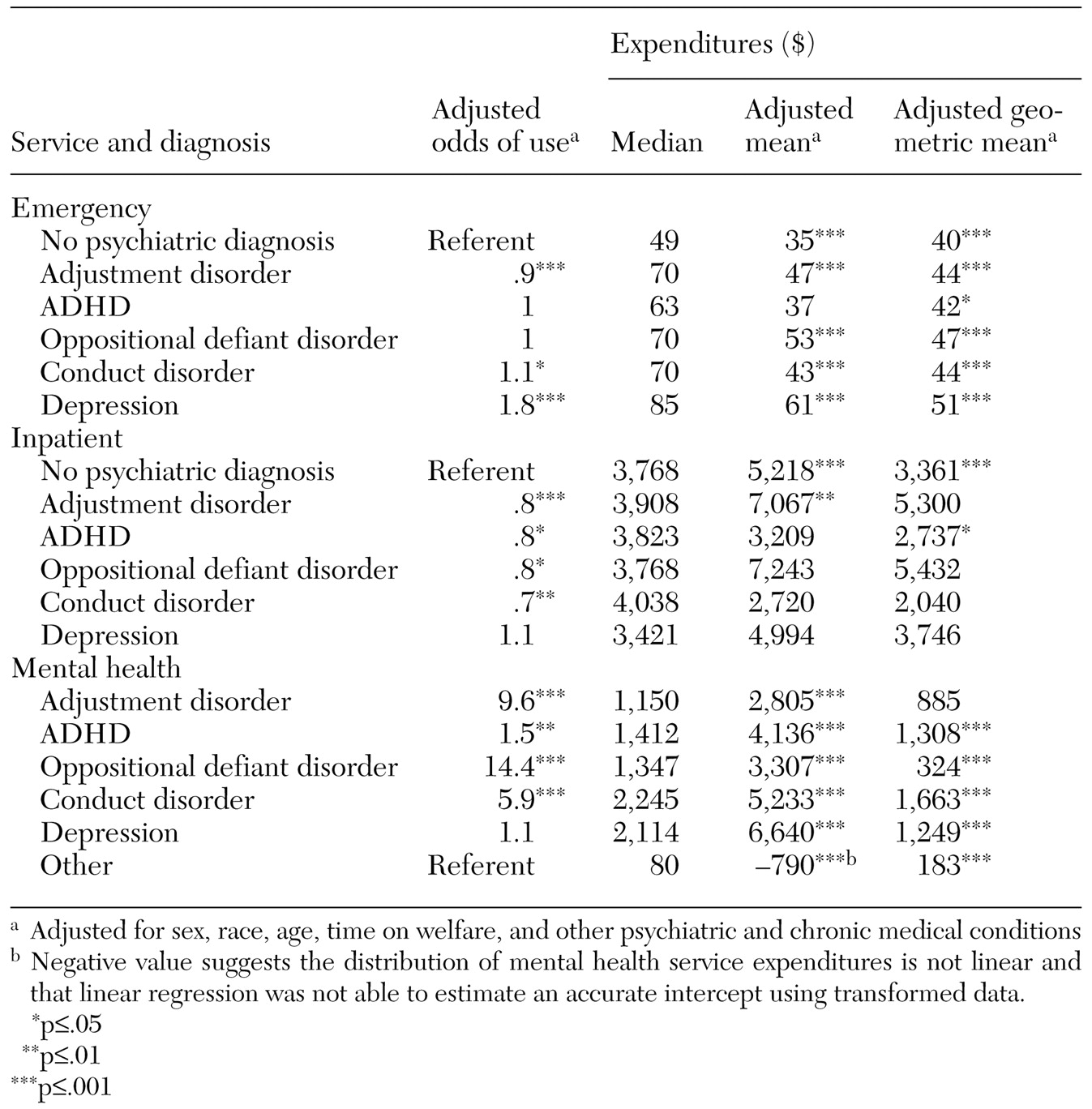

Table 2, and odds of use of emergency services, inpatient services, and mental health services and associated expenditures among children who used such services are in

Table 3.

Discussion and conclusions

Our results are similar to those of previous studies in terms of the proportion of children using mental health services (

3) and the proportion with ADHD (

1,

2,

3,

4). As in these other studies, total expenditures were much higher for children with ADHD than for other children. Like Guevara and colleagues (

3), we found that the bulk of total expenditures for these children was associated with mental health care. We extended the work of previous studies by examining the effect of a diagnosis of other prevalent psychiatric disorders and by adjusting for the presence of a number of chronic physical conditions. We found that the presence of any psychiatric disorder was associated with increased costs and that depression and conduct disorder were associated with the highest total costs.

The study had some limitations. Expenditures often include expenses and margins that may not reflect the true costs of services. However, it is likely that the expenditure estimates presented here underestimated true costs, because Medicaid rates during this period were inadequate to cover total related costs (

12), and the data do not reflect other sources of medical expenditures. Another limitation concerns the validity of diagnoses. The two-claims method has been used previously to identify the presence of psychiatric disorders and has been validated to determine the presence of serious mental illness among adults (

13), but it has not been validated for use with children. Finally, our data came from a single location with a population of low socioeconomic status. The findings may not be generalizable, although the results may be easily replicated with other administrative data sets.

These results have several important implications. Although previous studies have found that children with ADHD use more services and have higher associated costs (

1,

2,

3,

4), this study is the first to report a similar finding for children with other disorders. Of particular interest, children with depression were more likely to use emergency and ambulatory care services and to have higher expenditures associated with almost every type of service. These results are similar to those reported for adults, among whom depressive symptoms are associated with greater use of physical and mental health services (

14).

Depression is associated with many chronic physical health conditions that are associated with high costs (

15). However, our analyses controlled for many conditions, suggesting that there were other reasons for increased costs. Whatever the explanation, pediatric providers should be attentive to both physical and psychiatric complaints often associated with depression.