Participants and setting

The study participants were 54 women with

DSM-IV diagnoses of either schizophrenia (33 of 54, or 61 percent) or schizoaffective disorder (21 of 54, or 39 percent) and current illicit-drug abuse or dependence (past three months). All women were receiving outpatient mental health treatment at inner-city community-based clinics affiliated with the University of Maryland (N=51) or the Veterans Administration Medical Center (N=3) in Baltimore and were stable psychiatrically. The mean±SD positive-symptom clinical rating from the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (

17) (range, 0, not at all, to 7, extreme) was 2.54±.71, and the negative-symptom rating was 2.52±.7. The additional eligibility criteria included an age range of 18 to 65 years. Exclusion criteria were mental retardation and a documented history of seizure disorder or head trauma with loss of consciousness. Baseline data for the 54 women were collected from March 1999 to June 2002 for a longitudinal study of trauma among women with schizophrenia and substance use disorders.

The mean±SD age of the women was 40.6±6.8 years. The women had completed a mean of 10.9±2 years of school. Of the total sample, 50 (92 percent) were African American, 37 (69 percent) had never been married, 47 (87 percent) met criteria for either illicit-drug abuse or dependence, and eight (14 percent) met criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence only. Forty-two percent of the participants met criteria for both illicit-drug abuse or dependence and an alcohol use disorder. As the primary drug of abuse, 45 (84 percent) of the women who used drugs reported cocaine, six (11 percent) cannabinoids, and two (4 percent) opioids.

Medical charts were reviewed to determine preliminary eligibility for the study. Therapists of eligible patients were then asked whether patients were sufficiently psychiatrically stable to provide informed consent. All potential participants took part in a standardized informed-consent process with trained recruiters. Individuals were read the informed-consent document and were then asked questions about the study requirements and the risks and benefits of study participation to determine whether they clearly understood what was being asked of them. Women who were unable to answer these routine questions were reread the consent document and asked again, and women unable to understand the study requirements were excluded. All assessments and procedures were reviewed and approved by the university and the VA Maryland Health Care System institutional review board.

Assessment measures

Each participant was administered a four-hour assessment battery over a two-day period. All research interviewers were women who had master's or doctoral degrees. The first author trained the clinical interviewers with reading materials, training tapes, and live supervision. Interviewers approved for beginning the assessments attended weekly group supervision sessions where videotaped assessments were reviewed and discussed. Ongoing interrater reliability was maintained by obtaining consensus on ratings of symptom intensity and severity as well as diagnosis for randomly selected study participants during weekly supervision sessions.

Diagnosis and symptom assessment. Information about current symptoms and psychiatric history was obtained with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (

18). To evaluate diagnoses of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and substance use disorders, the SCID was used, as well as all available information for the patient—the patient's self-report, medical records, and information from treatment providers. The interrater reliability rating (kappa) for the SCID diagnoses (psychiatric disorders and substance abuse or dependence), based on ratings of 21 randomly selected cases, was greater than .80. Patients for whom diagnoses were uncertain were considered ineligible to participate. This group included all patients whose psychotic symptoms were judged to be substance induced.

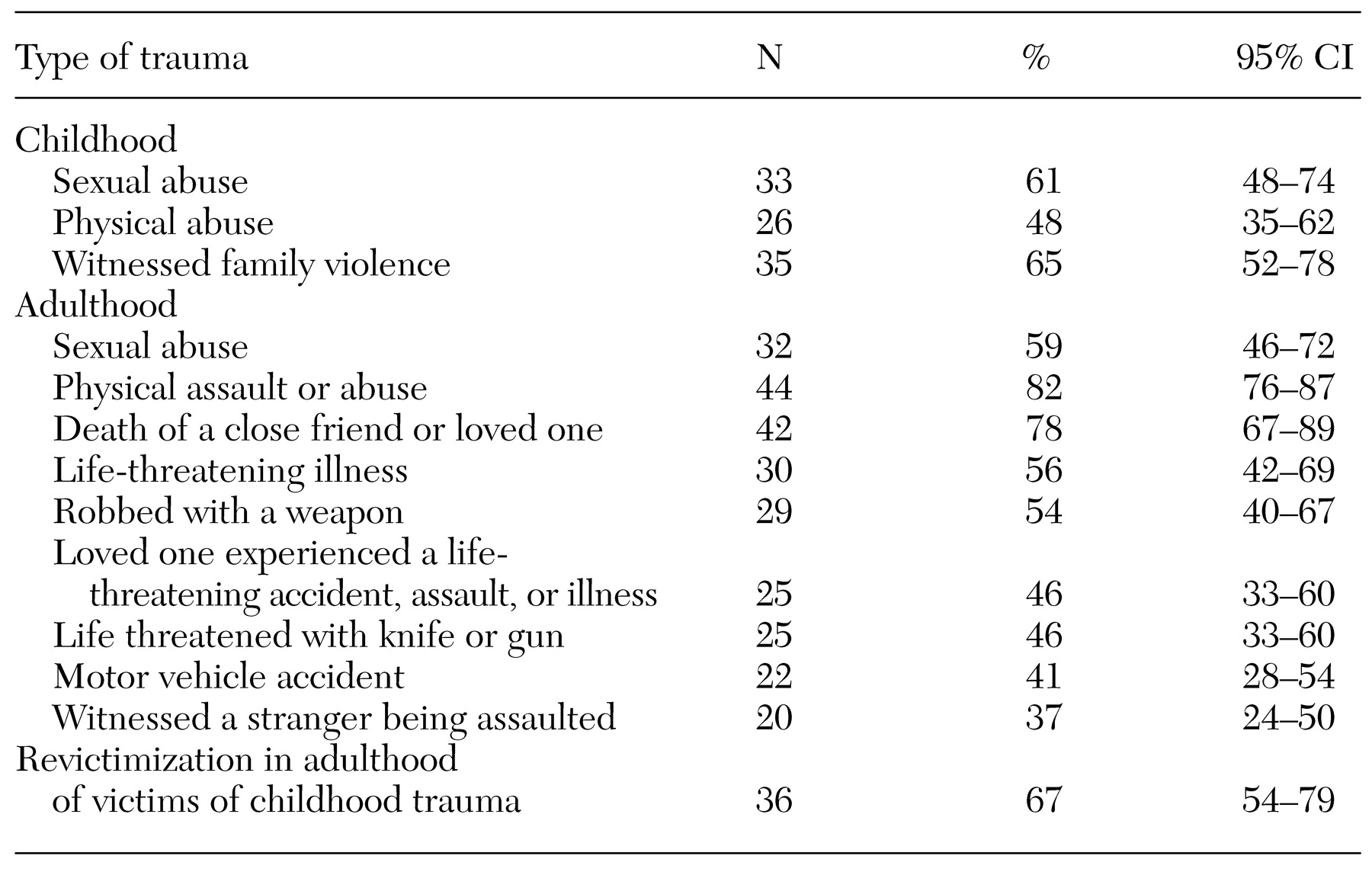

Lifetime trauma history assessment. Lifetime trauma history was assessed with the Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire (TLEQ) (

19). This instrument covers a range of commonly assessed childhood and adulthood events. The interview assesses both exposure to the event and individuals' subjective reaction to the event. Assessing subjective reaction—for example, self-reported feelings of terror, horror, or threat to life—is necessary for determining whether the event can be considered a

DSM-IV criterion A event for PTSD.

Evidence indicates that the reliability over time of self-reports of trauma by women with substance use disorders and schizophrenia is quite satisfactory. Fourteen participants in our study were administered the TLEQ at baseline and then again seven to 10 days later. Kappa coefficients were calculated to determine agreement for the presence or absence of adult sexual and physical abuse as well as for the number of traumatic events reported. A kappa of .85 was obtained for adult sexual victimization, .60 for adult physical victimization, and .76 for the total number of lifetime traumatic events reported. Other studies have demonstrated good reliability for the reports of sexual and physical abuse by people with serious mental illnesses (

20,

21; unpublished paper, Gearon JS, Bellack AS, Tenhula W, 2003).

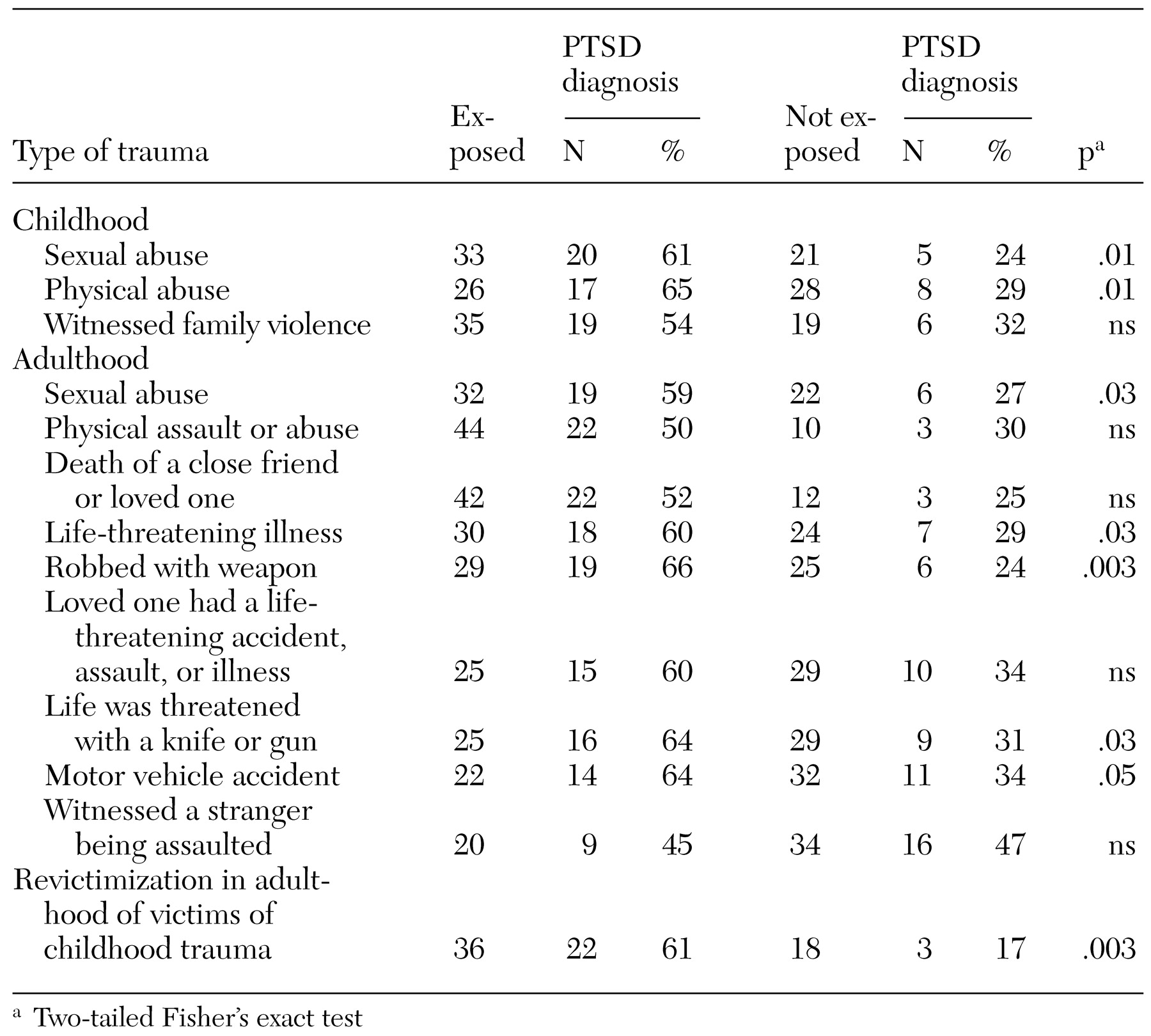

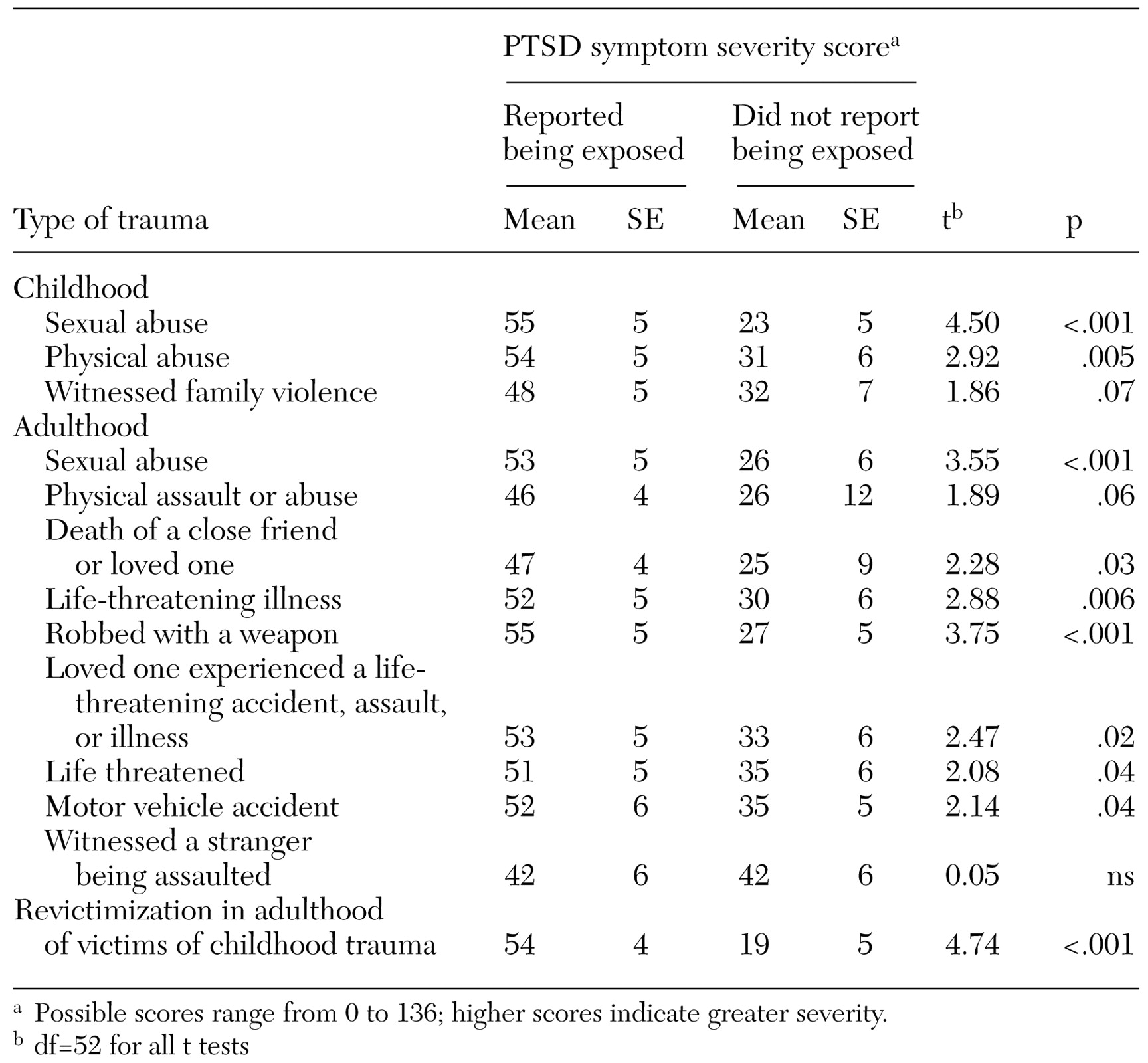

Assessment of posttraumatic stress disorder. The Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) (

22) is a clinician-administered interview that measures PTSD diagnostic criteria. The CAPS was developed to enhance the validity and reliability of PTSD diagnoses. Each of the 17

DSM-IV PTSD symptoms is rated on a scale of 0, low, to 4, high, for both frequency and intensity. PTSD symptom severity is computed by summing the frequency and intensity scores for the 17 items. The PTSD diagnosis was established by using the recommended cutoff of total severity of symptoms: 45 or higher (

23). This cutoff criterion was selected to enable us to compare our findings with those observed in previous studies: Meuser and colleagues' (

6) preliminary study of PTSD and trauma among patients with serious mental illness, as well as several existing studies of PTSD among substance-abusing women from the general community (

9,

10,

11) that used screening criteria or self-report instruments.

The CAPS offers a more rigorous and valid approach for estimating the prevalence of PTSD than does a brief screening or a self-report instrument, because it is an interview relying on clinical judgment. The interview also provides explicit anchors and behavioral referents for guiding ratings, which gives it reliability and validity above and beyond that of other instruments assessing PTSD.

The CAPS was adapted for use with patients with schizophrenia by making symptom descriptions more concrete and by providing more behaviorally specific examples. For example,

DSM-IV criterion C1, "efforts to avoid thoughts, feelings, or conversation associated with the trauma," is assessed with multiple questions, including these: "Have you tried not to talk to people (like your therapist, case manager, psychiatrist, friends, or family) about the event? Is it hard to talk about it now? Are you trying to push away thoughts or feelings about the event right now?" On the basis of Kessler's recommendation (

12), and because the majority of women with schizophrenia have experienced multiple traumatic events, questions about intrusion and avoidance that are typically asked in reference to a particular traumatic event were asked with respect to the range of traumatic experiences the participants reported.

Interrater reliability for our PTSD interviewers was excellent: intraclass coefficients for the symptom clusters and total severity of symptoms ranged from .97 to .99 for a subsample of eight participants, five of whom had a current diagnosis of PTSD. The level of agreement between interviewers in PTSD diagnosis, as indicated by the kappa coefficient, .90, was excellent as well.

Indexes of internal consistency suggest that the CAPS is internally stable and reliable. Coefficient alphas indicate that criteria in each of the three symptom clusters—for example, reexperiencing, avoidance, and arousal—and the total severity of symptom scores represent unified constructs. For our study participants, alpha was .91 for reexperiencing, .82 for avoidance, .86 for arousal, and .76 for the total severity of PTSD symptoms. The CAPS total symptom severity score and the three-symptom cluster scores appear to be reliable over time as well. Intraclass coefficients calculated at baseline and then again seven to ten days later for 14 participants were all satisfactory: reexperiencing, .62; avoidance, .80; arousal, .79; and total severity, .85.