The delivery of mental health services changed substantially during the 1990s in the United States, largely through cost-driven reductions in inpatient care. In the private sector, for example, the use of inpatient services has declined by about a third in recent years (

1,

2,

3,

4). Major transformations have also occurred in the public sector (

5,

6) and are well documented for the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) mental health care system (

7). Between fiscal years 1994 and 1997, the VA eliminated 5,987 mental health beds nationally, nearly 45 percent of the 1994 total of 13,571 beds (

8).

Despite increasing pressures to reduce inpatient services and bed capacity, studies that have evaluated the consequences of recent changes in the mental health system are limited. Studies of the impact of Medicaid managed care on clinical outcomes have been initiated (

9); some of these reported worse outcomes (

10), but others did not (

11,

12). However, none of these studies focused on the effects of large-scale bed closures. Several studies of the impact of bed closures and other efforts to curtail mental health inpatient costs in the VA system have recently been published and have shown little or no association with outcomes such as cross-system use of psychiatric services (

13,

14), rates of incarceration (

15), and reduced treatment effectiveness for posttraumatic stress disorder (

16). Although the studies have focused on veterans with severe mental illness, many of whom require brief, episodic inpatient care, they have not specifically examined the effects of bed closures on the most vulnerable inpatients—those who have been hospitalized for an extended period, such as a year or more.

Recent studies of non-VA state hospital downsizings and closings have focused to a greater extent on long-stay populations and have reported improvements in level of functioning and quality of life (

17,

18) but not full community integration (

19) after discharge. Although these studies provide important evidence that even persons hospitalized for prolonged periods can do well after discharge, they are somewhat limited in that they typically reflect the closing of a single facility rather than more systemwide changes. In addition, studies of the process of deinstitutionalizing state psychiatric patients have often focused on the results of legal mandates or consent decrees through which funds have been specifically set aside to enhance community-based services and to monitor outcomes (

20,

21,

22). Moreover, these case studies, which have evaluated a particular state's efforts to reduce inpatient care, have not shed light on the potential impact that more naturalistic, ongoing changes in a mental health system might have on different cohorts of long-stay patients over time.

In the study reported here, we used national VA administrative data to identify and prospectively follow up three cohorts of long-stay inpatients, defined as those who had been hospitalized for at least a year. Spanning a period of accelerated change in the VA mental health system, the data for the three cohorts were drawn from the early, middle, and late 1990s, respectively. We were interested in determining whether the proportion of long-stay patients being discharged from inpatient units increased over time and whether there were any changes in discharge destination among the patients who were discharged. In addition, we sought to determine whether there were substantial changes in three-year mortality rates across cohorts and in the extent to which discharged patients continued to have contact with the VA system after discharge.

Methods

Subjects and procedures

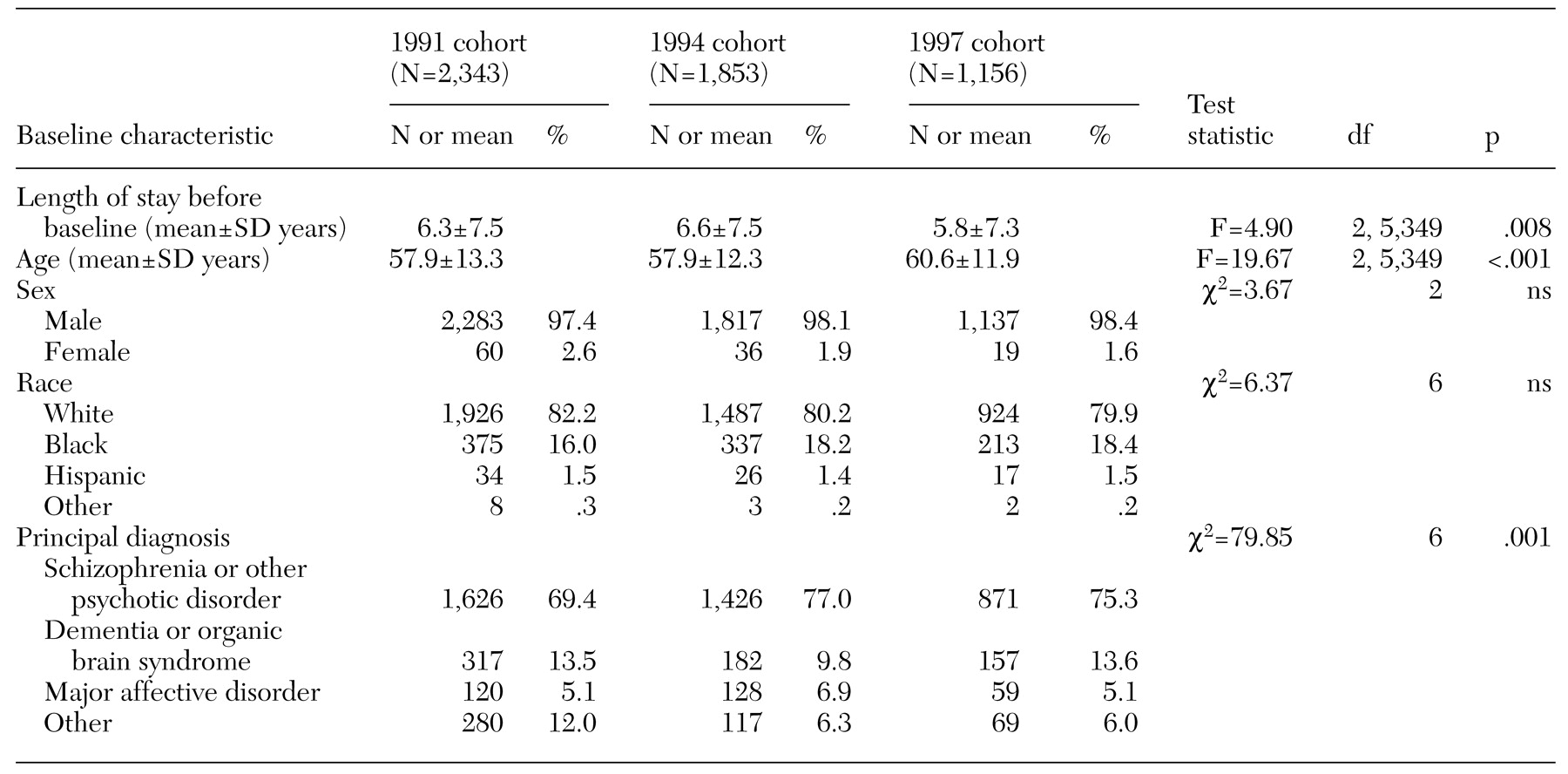

An annual census is conducted of all current VA inpatients at the end of every fiscal year (September 30). For each inpatient, an administrative record is generated that includes data on factors such as demographic characteristics (for example, age, sex, and race), date of admission, bed section, and principal diagnosis. We used census files from fiscal years 1991, 1994, and 1997 to identify and describe three cohorts of long-stay patients, defined as inpatients occupying psychiatric or substance abuse beds who had a length of stay of at least one year at the end of the fiscal year. The years 1991 and 1994 were selected because they correspond to periods before and at the start of, respectively, accelerated bed closures in the VA system; 1997 was chosen because the process of closing beds was well under way at that time (

8).

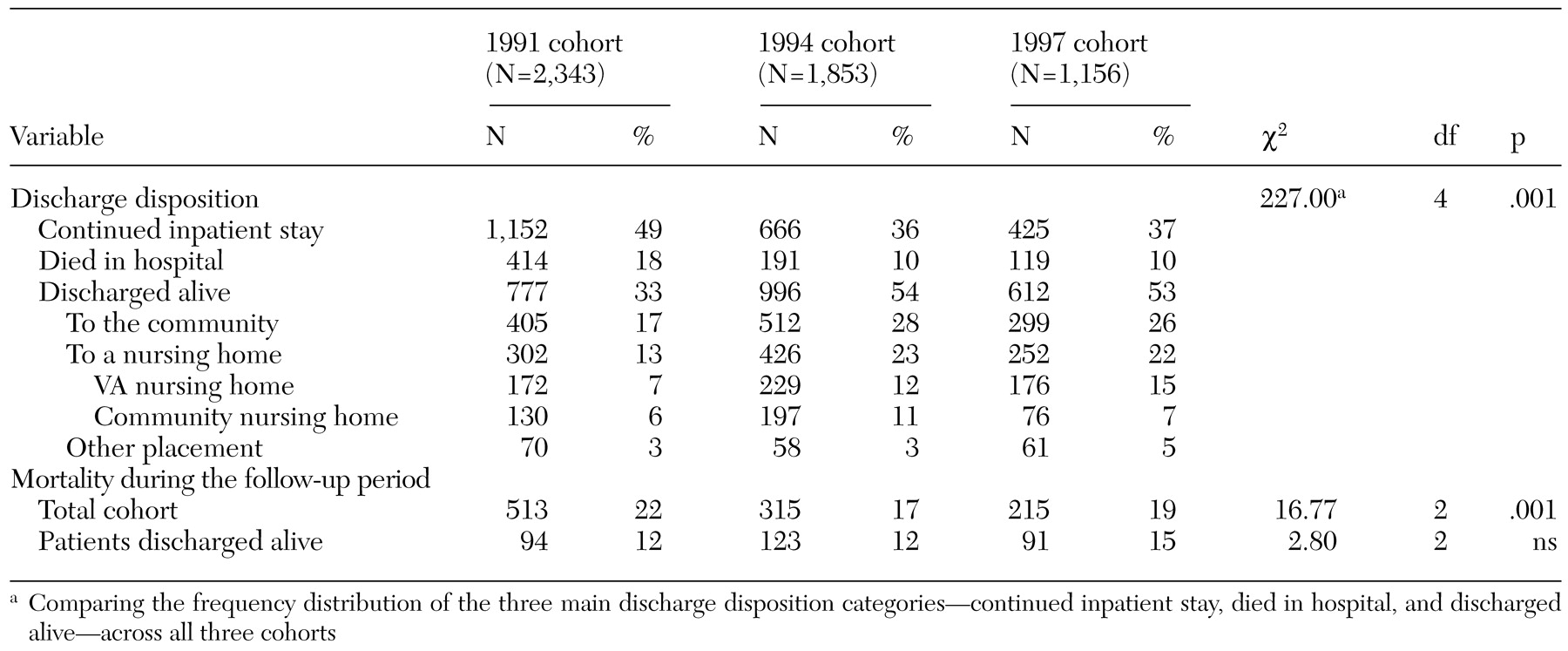

For patients in each cohort, we determined the discharge disposition and vital status over a three-year follow-up period, ending on September 30 of 1994, 1997, and 2000 for the three cohorts, respectively. Discharge disposition was determined by using census files from subsequent years as well as the VA Patient Treatment File, a national discharge abstract database that documents all discharges from VA inpatient facilities. We categorized patients' discharge disposition as one of the following: discharged to the community, discharged to a VA nursing home, discharged to a community nursing home, other placement (for example, a halfway house or a boarding house), died in the hospital, or continued as an inpatient. Because many long-stay patients were discharged from the hospital only to be readmitted shortly thereafter, we considered readmissions that occurred within 30 days to be continuations of the index inpatient stay. Thus, for the purposes of this study, long-stay patients had to be out of a VA hospital for more than 30 days in order to be considered successfully discharged.

In addition to documenting trends in discharge disposition, we examined differences in overall mortality among the three cohorts. For each cohort, we calculated the three-year mortality rate for all patients as well as the specific mortality rate for those who were discharged alive. Data on inhospital deaths obtained from the Patient Treatment File were supplemented with mortality data from the VA's Beneficiary Identification and Records Locator Subsystem (BIRLS), a computerized database of deceased veterans who have received VA death benefits. In terms of completeness of mortality ascertainment in the veteran population, the BIRLS has been shown to be comparable to alternatives such as the National Death Index (

23) and records of the Social Security Administration (

24).

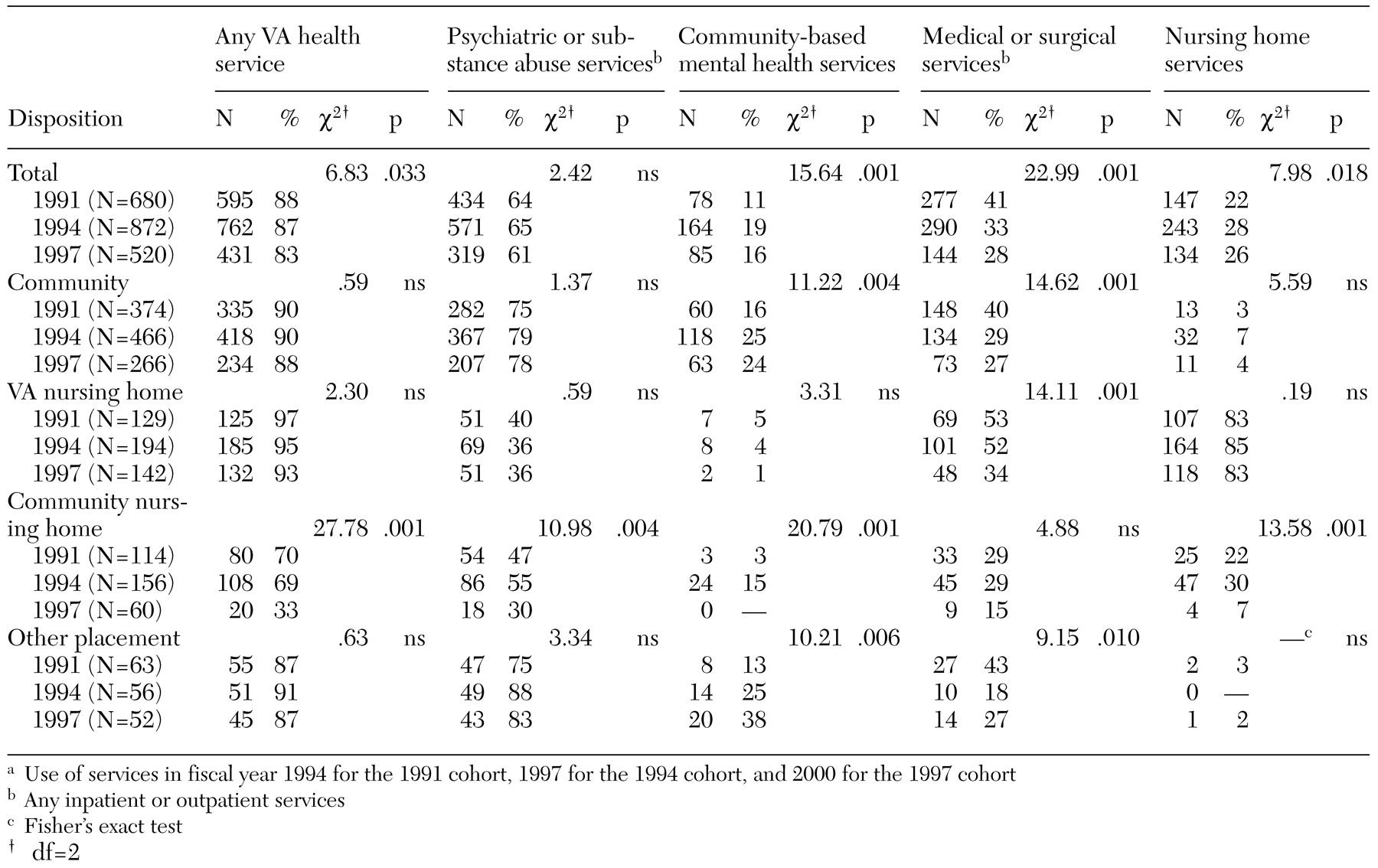

Finally, to gauge the extent to which patients who were discharged to different settings in the three cohorts remained connected with VA health services, we used administrative workload data to determine use of services during the third year after baseline (fiscal year 1994, 1997, and 2000, respectively, for the three cohorts). Specifically, we determined whether discharged patients who survived the follow-up period received any inpatient or outpatient psychiatric or substance abuse services, community-based mental health services (for example, VA community residential care and intensive case management), inpatient or outpatient medical or surgical services, nursing home services, or any of these VA health services.

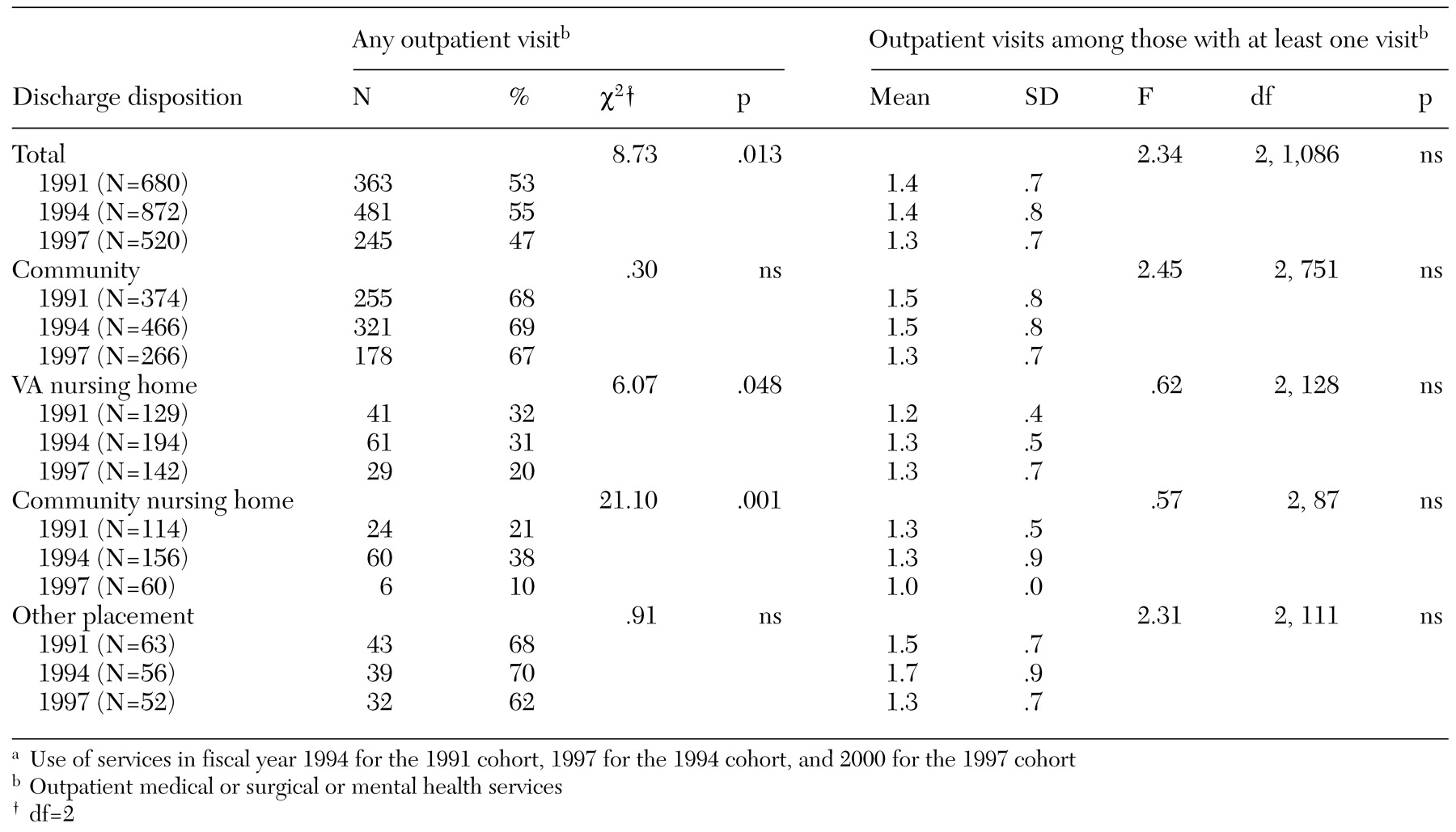

Among patients who made at least one outpatient visit, we also determined the mean number of visits in order to gauge the intensity of service use. Service use data were obtained from computerized national workload files, including the Patient Treatment File, the Outpatient Care File, and the Extended Care File, which, taken together, document all episodes of VA care.

This study was approved by the institutional review board of the VA Connecticut Healthcare System.

Data analysis

Differences in baseline characteristics, discharge disposition, mortality rates, and service use across the three cohorts were compared by using analysis of variance F tests for continuous variables and chi square tests for categorical variables. All analyses were performed with SAS version 6.12 (

25).

Discussion

During the mid-1990s, the Veterans Health Administration was restructured into a more decentralized system of 22 semiautonomous Veterans Integrated Service Networks serving geographically defined populations (

26). As part of the restructuring process, administrative directives and financial incentives were used to transform the VA health care system from one focused on acute inpatient care and medical specialization to one grounded in outpatient and primary care.

Between fiscal years 1995 and 2000, the number of veterans receiving inpatient mental health care decreased by 38.5 percent (from 123,217 to 75,745), whereas the number receiving outpatient mental health care increased by 23.2 percent (from 545,004 to 671,368); this change in mental health service delivery was associated with a 24.9 percent reduction in per patient cost (from $3,560 to $2,673) (

8). It was within this context of rapid and substantial service system changes that we sought to examine recent trends in discharge disposition, mortality, and service use among VA long-stay psychiatric patients—an especially vulnerable subgroup of mental health service users.

We found that, nationally, the number of occupied long-stay beds decreased by 50 percent between the end of fiscal year 1991 and 1997. Over time, there were significant changes in the principal diagnoses and discharge dispositions of long-stay patients. However, among patients who were discharged, no substantial differences were noted in either mortality rates or overall use of VA services across the three cohorts.

Compared with the 1991 cohort, the 1994 and 1997 cohorts included a significantly higher proportion of patients with a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia or another psychotic disorder. To some extent, this shift may reflect the greater likelihood of discharge among inpatients who have less severe psychiatric disorders and retention of those with behavioral problems and tendencies that would complicate subsequent placement (

27). Fisher and colleagues (

28) found that 69 percent of long-stay patients in Massachusetts state hospitals had exhibited a significant problematic behavior—for example, committed physical assault or had violent episodes—in the previous 30 days.

Between the 1991 and the 1994 cohorts, there was also a significant shift in readmission and discharge disposition. Discharge was attempted but unsuccessful (readmission within 30 days) for a greater proportion of patients in the 1994 cohort than in the 1991 cohort. Nevertheless, more than half of the patients in the 1994 cohort were discharged from the hospital for more than 30 days by the end of the three-year follow-up period, compared with a third of the patients in the 1991 cohort.

With the accelerated pace of VA bed closures well under way, the pattern of readmission and discharge disposition was nearly identical in the 1994 and 1997 cohorts. An exception was an apparent shift away from placement in community nursing homes in favor of VA nursing homes. It is not clear from these data what motivated this change. However, it is possible that a serial discharge process is in effect, such that patients are first discharged to a VA nursing home for a relatively short stay and then transferred to a community facility.

A notable finding of this study was that, among patients who were discharged, no significant change was noted in mortality rates during the three-year follow-up period across the three cohorts. This finding is consistent with those of studies that showed little or no adverse impact of VA bed closures on other outcomes, including rates of incarceration (

15) and cross-system use of state psychiatric services (

13,

14). As these earlier studies have indicated, many VA facilities coupled inpatient bed closures with increased expenditures on outpatient and community care. The expansion of outpatient capacity in conjunction with inpatient downsizing may reduce the risk of adverse outcomes.

Among surviving patients who were discharged, the overall use of any VA health services in the third year after baseline was high in all three cohorts—more than 80 percent—suggesting that a majority of patients remained at least somewhat connected with the VA system. The patients who were discharged to community nursing homes were the least likely to receive any follow-up care. Data on the use of non-VA services were not available, so we do not know the extent to which these and other patients may have substituted services in other health care settings for VA care. This limitation of the data is particularly striking given the low intensity of use of VA outpatient services in the three cohorts.

It is also unclear why the use of VA services declined so dramatically among patients who were discharged to community nursing homes in the 1997 cohort compared with those in the other two cohorts. Although it is possible that this finding reflects an idiosyncrasy of the small sample, future studies should seek to examine the reasons for and potential implications of this decline in connectedness with VA services.

Several limitations of this study deserve comment. First, as is often the case in record-linkage studies of this kind, the database merges were based on a single personal identifier—Social Security number—and some matches may have been missed because of miscoding. Second, the validity of the administrative data we used is unknown. However, the general validity of VA administrative data has previously been demonstrated (

29). Third, mortality and service use are somewhat blunt measures of patient outcome. Information was not available on outcomes such as clinical status, quality of life, and functioning after discharge. Such data are costly to collect and are rarely gathered before the implementation of major service system changes, thereby making follow-up comparisons difficult to perform. However, in case studies in which these kinds of data have been collected, the results have been encouraging in terms of demonstrating improvements in level of functioning and quality of life (

17,

18).

Fourth, data were not available on comorbid medical conditions, which potentially limits the interpretation of mortality estimates. Finally, because some patients belonged to more than one cohort, the three groups were not entirely independent. Thus computed chi square and F statistics were overestimated, and, accordingly, p values were underestimated. Nevertheless, even if one were to use a more conservative alpha level to test significance—for example, p<.01—similar conclusions would be drawn.