Methods

The study was conducted in the general internal medicine clinic (GIMC) of the Seattle VA Medical Center. The GIMC is organized into four groups of providers to which providers and their patient panels are assigned in an unsystematic manner (

33). At the start of the study period—January 1998 to March 1999—GIMC staff included 19 attending physicians, 38 residents, ten fellows, and 22 nurse practitioners. The clinic was supported by one full-time-equivalent (FTE) psychiatry resident, one clinical psychologist, one clinical psychology intern, four social workers, and two social work interns. Two of the four provider groups were randomly assigned to the collaborative care intervention and two to consult-liaison care.

We used several methods to locate eligible patients, including referral from two ongoing, unrelated studies (

34,

35); a prevention survey conducted at the clinic; and referral by primary care providers. After initial screening, each prospective participant was given a computer-assisted structured interview to assess the severity of depression, current and past use of medication or therapy, health status, current and past alcohol use, symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), history of mental illness, and barriers to care. Assessment of depression and anxiety symptoms was based on the PRIME-MD (

36), with additional questions taken from the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (

4). The interview was administered by an experienced psychology technician in person or by telephone.

Of 1,125 patients who were screened, 732 completed the assessment interview. Of these, 500 who had a current major depressive episode, dysthymia, or both were eligible to participate in the study. We limited the exclusion criteria to the extent possible in order to maximize the generalizability of the results and included patients receiving ongoing intensive treatment for depression, patients requiring treatment for substance abuse or PTSD before initiating depression treatment, and patients with acute suicidality, psychosis, or another condition requiring immediate treatment. The study enrolled 354 patients who consented to participate, 168 of whom were assigned to the collaborative care group and 186 to the consult-liaison care group. All procedures were approved by the human subjects committee of the University of Washington.

Clinical outcomes were assessed through telephone interviews three and nine months after enrollment. Follow-up assessments were completed for 146 patients (87 percent) in the collaborative care group and 164 (88 percent) in the consult-liaison group. There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between respondents and nonrespondents. These interviews included repeat administration of a 20-item depression scale extracted from the Symptom Checklist-90 (SCL-90) (

37)—the primary outcome measure—and other measures not presented here.

The collaborative care program was a multifaceted intervention that included diagnosis and treatment, patient education, and patient support and progress evaluation. The collaborative care team consisted of a clinical psychologist, a psychiatrist, a social worker, and a psychology technician. The team met weekly to develop treatment plans and conduct six- and 12-week progress evaluations. Treatment plans were developed on the basis of the VA's major depression guideline, taking into account current and previous treatment and patients' preferences. The team communicated with primary care providers by using electronic progress notes and tracked receipt and acknowledgement of notes and follow-up. If the agreed-upon prescriptions were not written in a timely fashion, the study team contacted the provider to discuss the recommendation.

Depression treatment options were to begin, increase the dosage of, or change the antidepressant medication; add an adjuvant medication; enroll in a cognitive-behavioral therapy group; schedule an appointment with the psychologist or the psychiatrist; or refer the patient to mental health specialty care (

38,

39). Options were selected in a stepwise fashion beginning with the least resource-intensive option. If later evaluations indicated that the option was not effective, a new or stepped-up option was recommended. No limits on specialty care visits were imposed.

The patient education component of the intervention included a videotape (

40) and a workbook, which were mailed to each patient. To evaluate the patients' progress and provide support to the patients, a social work staff member or student telephoned each patient on a regular basis to encourage adherence, address treatment barriers, and assess response to the intervention.

Consult-liaison care represented the traditional model in which the primary care provider was responsible for initiating treatment with consultation from or referral to specialist care as needed. To ensure that this approach was not merely a test of more versus less care, an explicit attempt was made to equate the amount of mental health resources available to each provider group, including the available time of the psychologist and social workers. Psychiatry residents' time was reserved for the consult-liaison provider groups. The supervising psychiatrist participated in the collaborative care intervention but rarely met directly with patients. All providers were notified of the diagnosis. Providers of consult-liaison care were able to refer patients to the psychiatry resident, psychologists, or social workers who were physically present in the GIMC. Patients with more complicated conditions were referred to specialty mental health clinics, facilitated by the study team. For both types of care, the primary care providers received three hours of instruction about assessment and treatment of depression (

41).

On the basis of the approach developed by Lave and colleagues (

24) and modified by Simon and colleagues (

25), SCL depression scores from baseline and follow-up assessments were used to calculate the number of depression-free days during the nine-month follow-up period. This method uses depression severity data from two consecutive outcome assessments to estimate the severity of depression for each day during the interval by linear interpolation. Days for which the SCL depression score was .5 or less were considered depression free. Days for which the SCL depression score was 2.0 or greater were considered fully symptomatic. Days with intermediate severity scores were assigned a value between depression free and fully symptomatic by linear interpolation—for example, a day with an SCL score of 1.25 would be considered 50 percent depression free. Calculation of depression-free days was limited to participants who completed all follow-up assessments.

Data on the use of VA care in the nine-month follow-up period were obtained from the local VA data warehouse, including outpatient visits, inpatient admissions, and outpatient prescriptions filled. We categorized visits as primary care visits, mental health specialty visits, or other treatment visits on the basis of clinic identifiers. Mental health specialty visits included visits to mental health, PTSD, or substance abuse clinics. A primary care depression visit was defined as a primary care visit with an ICD-9 code of 296.2, 296.3, 298.0, 300.4, 309.1, or 311, regardless of primary or secondary diagnosis.

Costs of care for the nine-month study period were estimated on the basis of national average cost estimates from the Cost Distribution Report (CDR), the VA's cost accounting system (

42). The CDR provides an average cost per visit in a specific clinic. The cost estimates included direct and indirect costs and were adjusted to year 2000 dollars by using the medical component of the consumer price index. The intervention costs that were not reflected in the utilization data—that is, team meetings and follow-up patient telephone calls—were estimated by sampling staff activity records and computing average cost on the basis of event duration by using actual input costs, such as labor, fringe benefits, and overhead costs. On average, team meetings lasted 56 minutes, involved discussion of 13 patients, and cost $403. Three follow-up calls were scheduled during the acute phase of treatment and five during the maintenance phase. Completed follow-up calls took 24 minutes—including preparation, unsuccessful attempts to call, and documentation—and cost $15 on average.

Our primary cost analysis was depression treatment cost, which included estimated costs during the nine-month period for all primary care depression visits, outpatient mental health specialty visits, antidepressant prescriptions, and the intervention program (for patients receiving collaborative care). In a secondary analysis, we considered total outpatient costs and total costs (inpatient and outpatient). However, the sample was not sufficiently large to provide statistical power to detect even moderate differences in total costs (

43).

Confidence intervals (CIs) for depression-free days and cost measures were estimated by bootstrapping with 1,000 replications (

44,

45,

46). Adjusted differences between collaborative care and consult-liaison care were estimated by using regression models with bootstrap interval estimates. All analyses were adjusted for baseline characteristics, including age, gender, race, marital status, living situation (whether the patient was living alone), previous depression, SCL depression score, Chronic Disease Score (

47,

48), and the logarithm of cost in the previous year. All models were also adjusted for interclustering correlation at the provider level by using Huber's estimator from a robust regression (

49,

50). All cost and utilization comparisons included the full study sample. The cost-effectiveness analysis included patients who completed all follow-up assessments.

Results

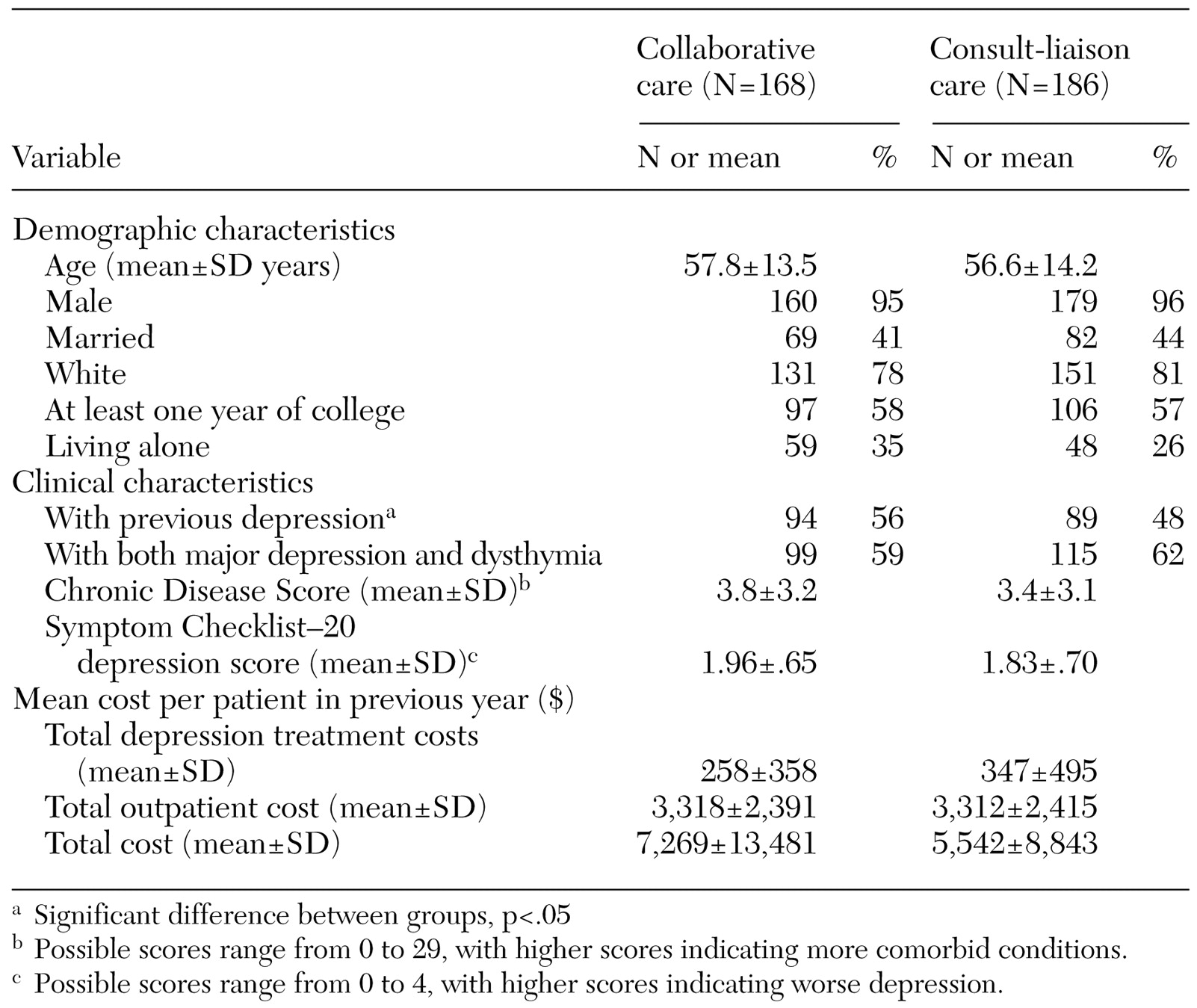

Baseline characteristics of the study participants are summarized in

Table 1. No significant differences between groups were noted in baseline demographic characteristics, SCL depression scores, or costs during the year before enrollment, except that the patients receiving collaborative care were more likely to have had previous depressive episodes than patients receiving consult-liaison care (56 percent compared with 48 percent, p<.05). The number of depression-free days in the nine-month follow-up period was calculated as the areas under the curves—that is, the proportion of depression-free days multiplied by follow-up time interval. By this measure, the mean±SD number of depression-free days was 112.7± 81.1 for the collaborative care group and 107.3±75.6 for the consult-liaison care group in the nine-month period. The proportion of depression free days in the collaborative care and consult-liaison groups, respectively, was 37 percent versus 36 percent at baseline, 43 percent versus 36 percent at three months, and 42 percent versus 41 percent at nine months. After baseline characteristics were adjusted for, the difference between the two groups was 14.6 days (p=.059, 95 percent CI=−.5 to 29.6).

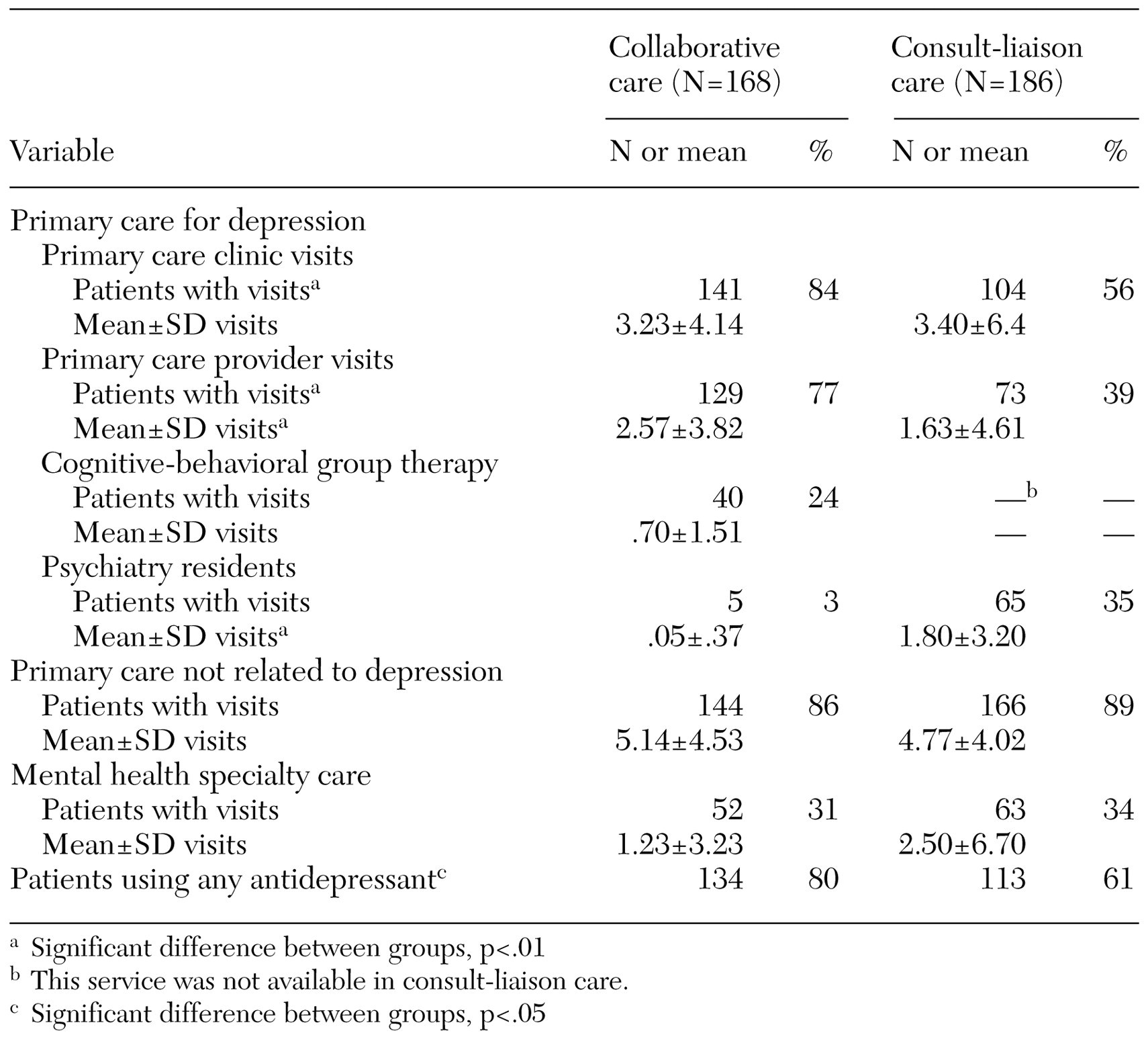

Use of VA aftercare in the nine-month follow-up period is shown in

Table 2. Compared with patients receiving consult-liaison care, those receiving collaborative care were significantly more likely to have a primary care depression visit (84 percent compared with 56 percent) and to be given a prescription for an antidepressant (80 percent compared with 61 percent). No significant differences were noted in the number of primary care visits, use of primary care for nondepression care, or use of mental health specialty services.

The utilization pattern reflects the study interventions. Patients in the collaborative care group were more likely to visit a primary care provider for depression treatment than those in the consult-liaison group (77 percent compared with 39), with significantly more visits per patient (2.57±3.82 compared with 1.63± 4.61). Twenty-four percent of the patients in the collaborative care group received cognitive-behavioral therapy. By intervention design, the patients who received collaborative care were less likely to be referred to GIMC psychiatrists than those in consult-liaison care (3 percent compared with 35 percent), with significantly fewer mean visits per patient (.05±.37 compared with 1.80±2.50).

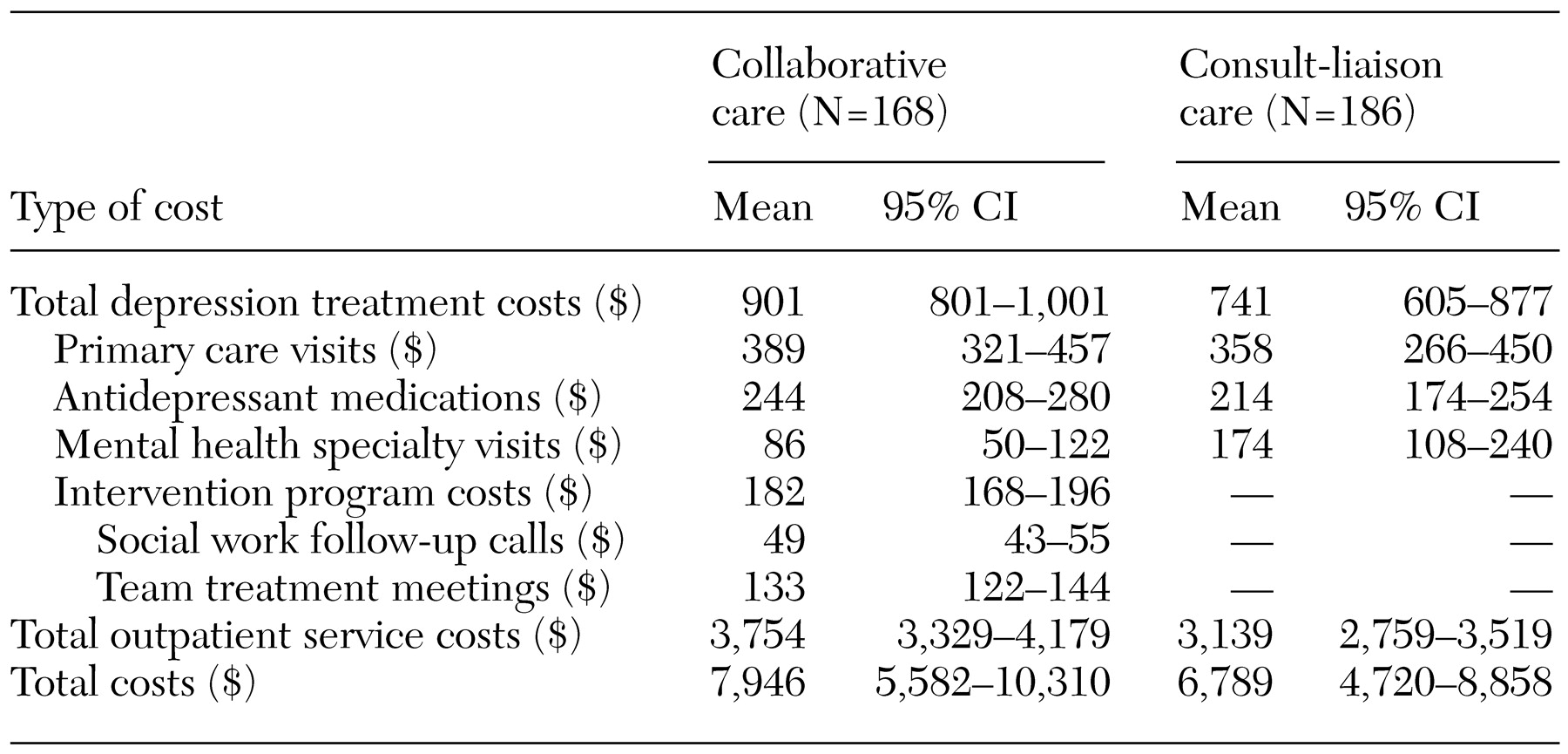

Table 3 shows the cost of care per patient for the nine-month follow-up period. The costs of depression treatment were approximately $160 higher for the collaborative care group, primarily because of the cost of intervention program ($182). The estimated cost for mental health specialty visits was greater for the consult-liaison care group than for the collaborative care group ($174 compared with $86). Greater differences between the two groups were found in broader categories of costs (a $615 difference in outpatient costs and a $1,257 difference in total cost). CIs increased as the cost category broadened, reducing the precision of the latter cost estimates.

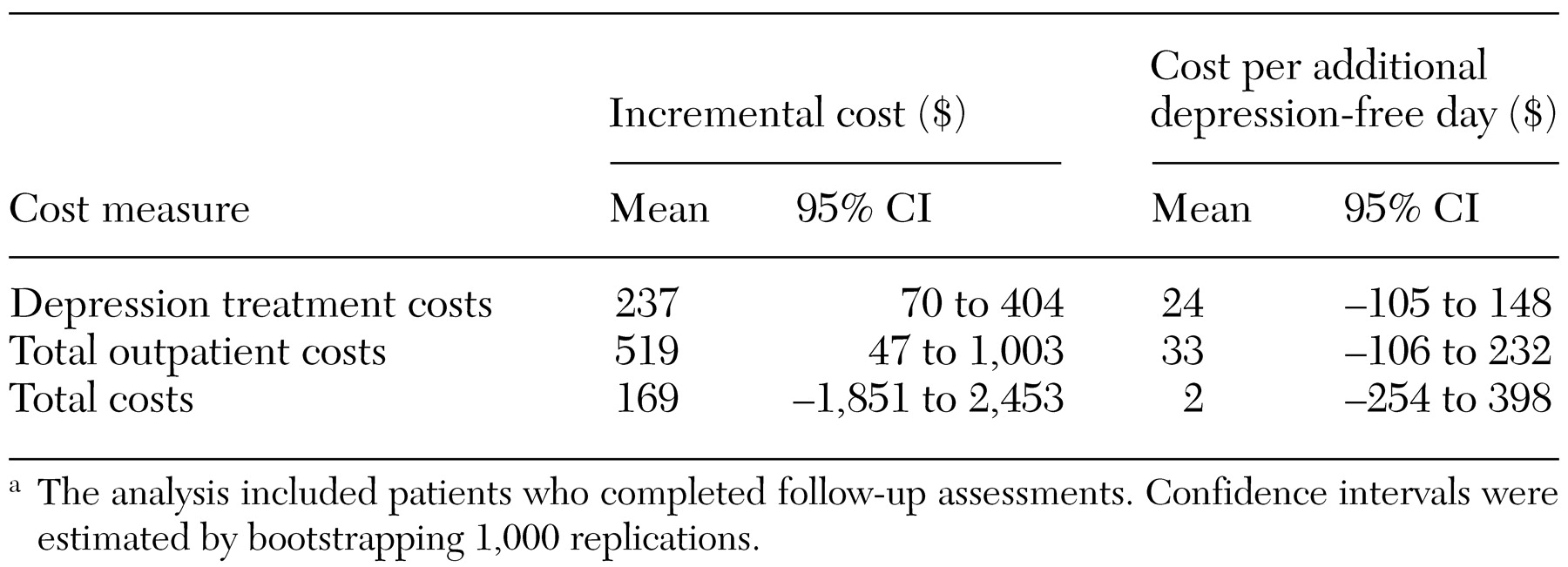

Adjusted incremental cost and cost-effectiveness of the intervention are shown in

Table 4. On average, the adjusted incremental cost of collaborative care was $237 for depression treatment costs (CI=$70 to $404) and $519 for total outpatient costs (CI=$47 to $519). For total cost, the adjusted incremental cost was considerably smaller ($169). For total outpatient cost and total cost, we could not conclude a finding of cost offset (negative incremental cost).

When only depression treatment costs were considered, the additional cost per depression-free day was approximately $24. On the basis of cost-effectiveness ratios for depression treatment costs, total outpatient costs, and total cost, we could not conclude a finding of absolute cost savings (negative incremental cost per depression-free day), because their CIs included zero. The wide CIs reflect the uncertainty in estimates of both incremental effectiveness and incremental cost.

Our final analysis examined the likelihood that either collaborative care or consult-liaison care would demonstrate both greater effectiveness and lower cost—in the jargon of cost-effectiveness, that one of the approaches would be "dominant." For depression treatment costs, consult-liaison care was found to have both greater effectiveness and lower cost only 34 times in 1,000 bootstrap replications, indicating a 3.4 percent probability that consult-liaison care would be dominant over collaborative care. We did not observe dominance of the collaborative care intervention in 1,000 replications. The results show a 96.6 percent probability that the collaborative care intervention would be associated with both increased cost and increased effectiveness.

Discussion and conclusions

We found that a collaborative care model designed to improve depression treatment in a veteran primary care population was associated with modest increases in time free of depression and in treatment costs over the nine-month study period. However, the difference in the number of depression-free days between groups was not statistically significant. This result was similar to the findings for a collaborative care model for depression relapse prevention for chronically depressed patients, who were more comparable in illness severity to our study patients (

28). The relapse-prevention program demonstrated 13.9 additional depression-free days (not significant), with an incremental cost of $273 for outpatient depression treatment cost in a 12-month period.

Our results are consistent with those of other depression treatment interventions in primary care, which suggests that additional resources are needed to achieve better outcomes for patients with major depression (

23,

25,

26,

27,

28). We did not find any cost-offset effect—that is, improved depression treatment was not associated with lower total outpatient care costs (

23,

25,

26,

27,

28). Instead, we estimated an average increment of $519 in total outpatient costs for collaborative care.

This intervention was developed on the basis of the availability of treatment resources in VA primary care clinics, including team treatment meetings, brief follow-up telephone calls, and cognitive-behavioral therapy. This intervention was less resource-intensive than Katon's models, which required either additional psychiatrist or psychologist visits during the treatment period (

16,

18). Furthermore, Katon's studies were conducted in a managed care network with a considerably different patient population. The patients in our study had a number of characteristics that predict difficulties with treatment, such as older age, male gender, less education, a higher rate of unemployment, and more chronic illness and comorbid psychiatric illness. Our findings demonstrate that even in a population that is very difficult to treat, systematically reorganizing the delivery of mental health services by using a collaborative care model enables more patients with depression to be treated in primary care with a modest incremental cost.

This evaluation was not intended to assess the cost-effectiveness of collaborative care compared with a control group of patients receiving no treatment for depression. The consult-liaison care provided to the patients in this study involved a fairly high level of mental health services. Thus our results imply that better communication and coordination between mental health and primary care providers can increase the number of patients treated, even in a primary care setting already providing a broad range of mental health services. Collaborative care may have larger effects when introduced in a system that has fewer mental health resources already in place.

The relatively low cost of telephone follow-up ($15 per call and $49 per patient) was due to the use of adjunctive clinical personnel to conduct this task. In the early stage of the intervention, the calls were made by GIMC social workers. Because of lack of system resources as the social workers' caseload and range of duties increased over time, the telephone calls were later made by students supervised by social workers. Experience with this study and other studies suggest that staff performing this care management function need telephone assessment and triage skills but do not need to be psychotherapists or prescribers (

31,

51). Our experience also implies that a successful adoption of population-based treatment care management through telephone follow-up will require identification of the appropriate clinic staff to perform this function and integration of this activity with other duties.

This study had several limitations. First, our results, based on a single site with existing mental health integration in primary care, may not be generalizable to other primary care settings. Second, this study did not include utilization and cost data for services obtained outside the VA. Third, the VA cost accounting method provides an average cost per clinic visit, which does not capture variation in outpatient cost across visits with different intensities of care. Finally, our calculation of depression-fee days was based on the SCL depression scale rather than the Hamilton Depression Scale used in previous studies.

Comparing these findings with those for other interventions requires use of a common measure of effectiveness, such as cost per quality-adjusted life year (QALY). The literature suggests that depression reduces the value of a life-year by .2 to .4 QALYs (

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57). On the basis of this range of conversion, our estimate of $23.50 per additional depression-free day would be equal to an estimated $21,444 to $42,838 per additional QALY for depression treatment costs, which was comparable to Katon's stepped collaborative care and relapse-prevention models (

25,

28). These results, consistent with those of other studies, compare favorably with those for a wide range of preventive and therapeutic services (

58,

59).