In the United States, the rates of hepatitis C infection differ by gender: 2.5 percent for men compared with 1.2 percent for women (

1). Among persons with severe mental illness, hepatitis C rates are higher and also differ by gender: 19.6 percent for men and 9.8 percent for women (

2). The gender differences in infection rates among persons with severe mental illness may reflect differences in patterns of risk behaviors or in the risk associated with a given behavior. However, few studies have examined gender differences in risk behaviors for hepatitis C infection, and none have examined these issues among persons with severe mental illness.

Understanding gender differences in risks and rates of hepatitis C infection among persons with severe mental illness may help clarify the role of sexual transmission. A study of HIV risks among persons with severe mental illness found female gender to be predictive of high-risk sexual behaviors (

3). The literature suggests that the hepatitis C virus may be spread sexually but less efficiently than HIV or hepatitis B. Although reports are mixed, estimates of sexual transmission of hepatitis C range from zero in some cohorts to 23 percent in high-risk cohorts (

4,

5,

6,

7). In one study, the rate of hepatitis C transmission from infected persons to their spouses (non-injection drug users) was 6 percent (

8). Another study reported evidence of sexual transmission of hepatitis C among women with or at risk of HIV infection (

9). A third study did not find evidence of sexual transmission of hepatitis C (

5).

In a large multisite study of infectious diseases among persons with severe mental illness, we investigated gender differences in the constellation of risk behaviors associated with hepatitis C infection and sought to answer three questions. First, does the prevalence of hepatitis C risk behaviors differ by gender? Second, does gender influence the risk of hepatitis C associated with a given behavior? Finally, do gender differences in hepatitis C risk behaviors account for the differences in hepatitis C infection rates between men and women?

Methods

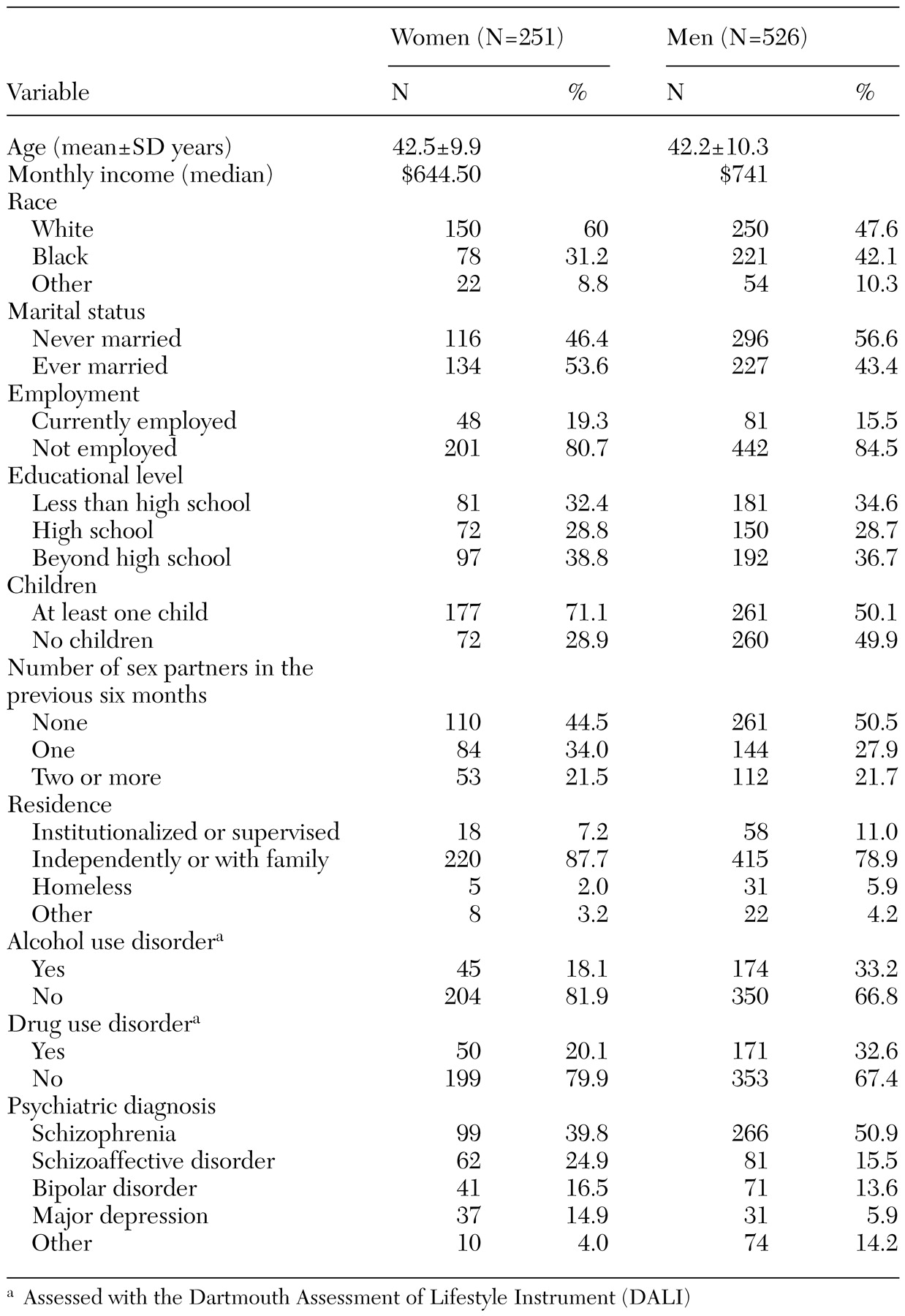

We performed a secondary analysis of data from a large multisite investigation of risk behaviors and sexually transmitted diseases among women and men with severe mental illness, described in the other articles in this special section of this issue of

Psychiatric Services (

10). We recruited 969 participants from five sites between June 1997 and December 1998. We excluded 192 participants at one site (Duke) who did not test positive for hepatitis C, which left a sample of 777. A detailed description of the sampling and data collection methods is provided elsewhere (

2).

We used the AIDS Risk Inventory (ARI) (

11) to assess risk behaviors that may be associated with hepatitis C infection. We assessed comorbid substance use disorders with the Dartmouth Assessment of Lifestyle Instrument (DALI), a sensitive and reliable measure for substance use disorders among persons with severe mental illness (

12). We tested for serum antibodies to hepatitis C with the Abbott enzyme immunoassay kit (

2).

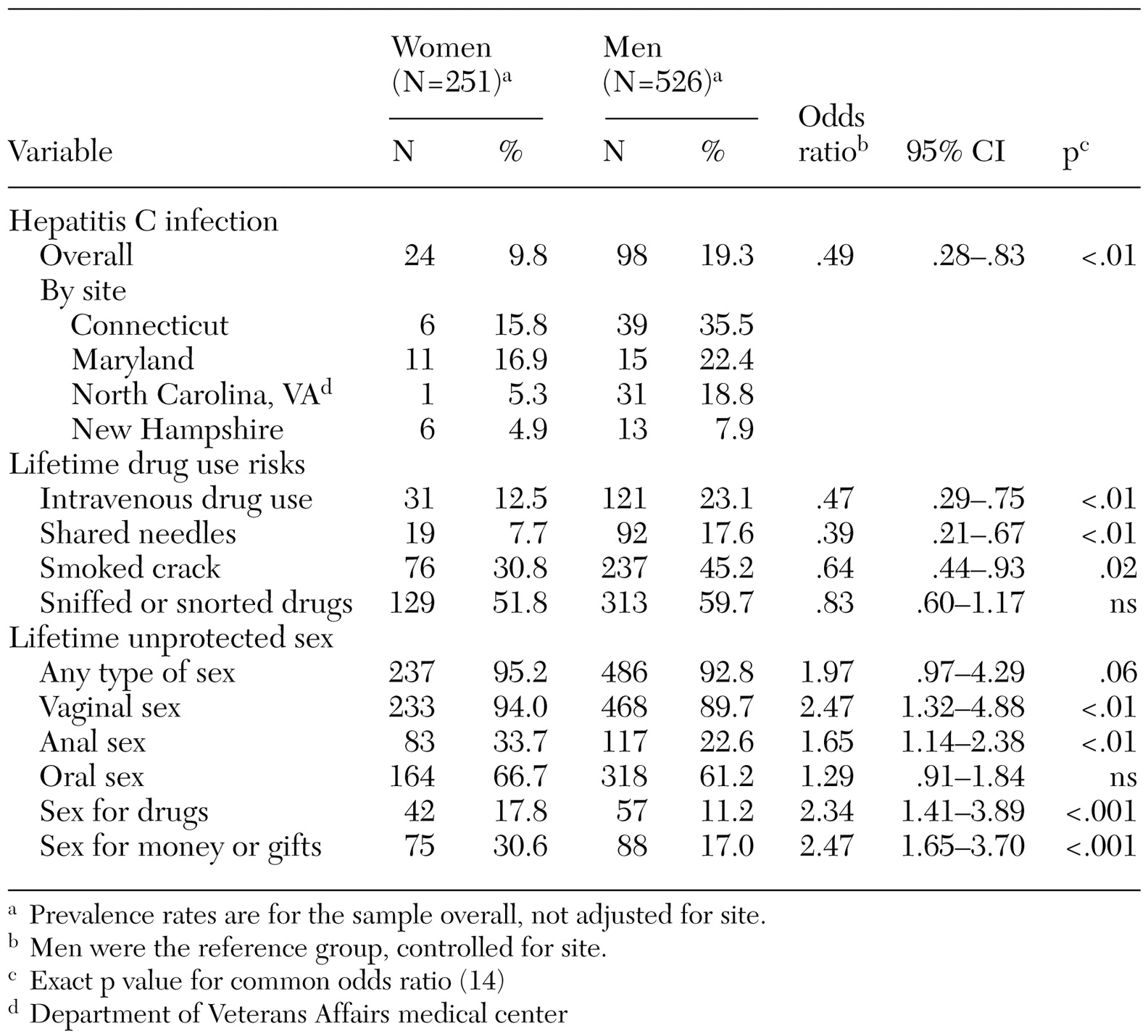

The primary outcome variable was hepatitis C serostatus. The primary independent variable was gender. The other key variables were lifetime risk behaviors, including drug risks, such as injection drug use and needle sharing, and sex risks, such as unprotected sex in exchange for money or drugs.

We stratified analyses by site because of the variability in demographic characteristics, recruitment, and sampling strategies. We assessed associations between gender and demographic variables with the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel, Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney, and Cochran-Armitage trend tests, depending on the distribution of the demographic variable. We assessed the bivariate relationships between risk and hepatitis C serostatus, risk and gender, and risk and hepatitis C serostatus for each gender. Common odds ratios (ORs) for each specified bivariate association were tested for homogeneity by the Zelen test for homogeneity of odds ratio (

13). If the test for homogeneous ratio was not rejected, a common OR was calculated by the exact inference method using StatXact software (

14). If the test for homogeneous odds ratio was rejected, an OR for each site was calculated and tested for significance within each site. Analyses used the SAS version 6.12 and the StatXact packages.

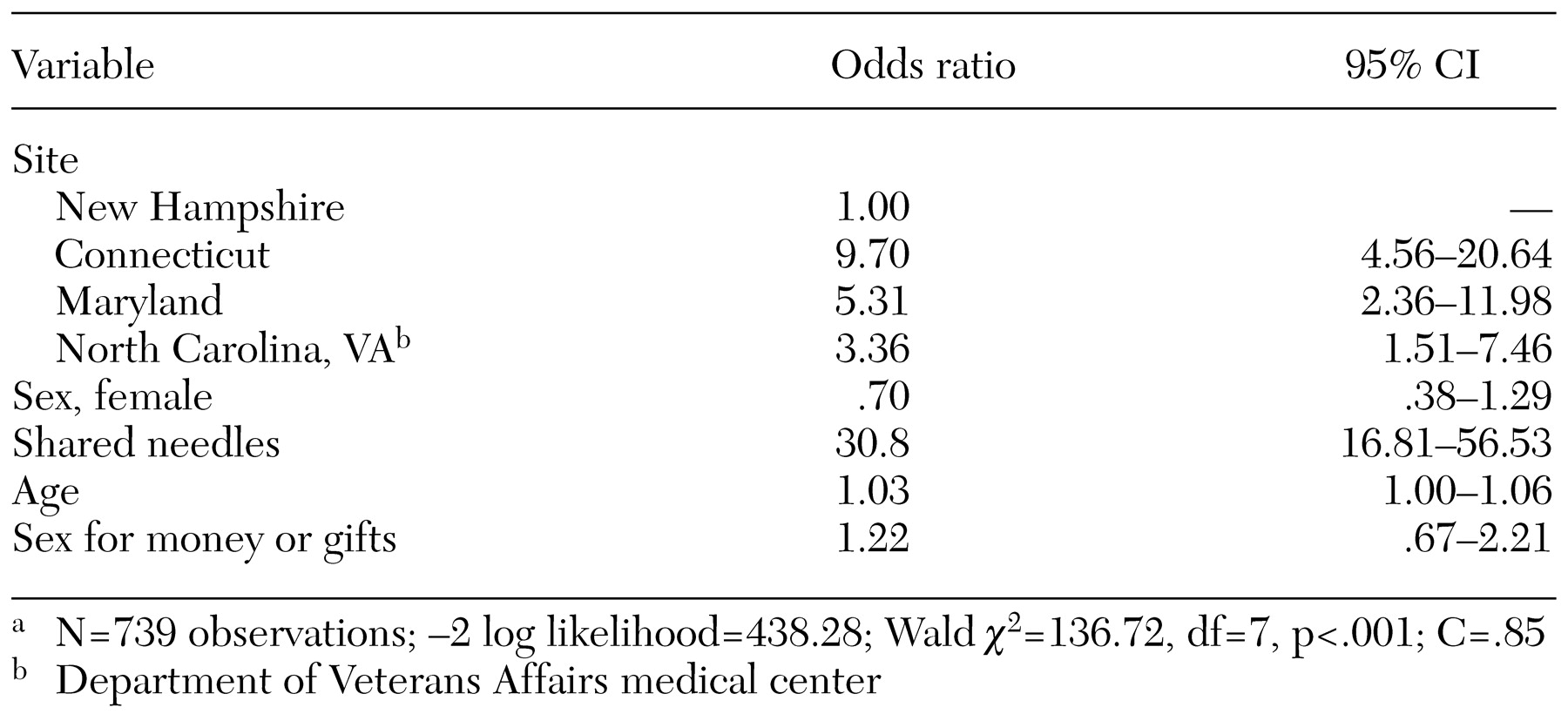

After assessing bivariate relationships, we performed a multiple logistic regression analysis, adjusting for site. Variables in the model were selected on the basis of their relative importance in the domains of drug- and sex-related risk behaviors and their relevance to research questions. We used casewise deletion to handle missing data in all statistical tests.

Discussion and conclusions

This is the first study to examine gender differences in behavioral risks and the relationship of these differences to the very high rates of hepatitis C reported for men and women with severe mental illness (

2). In addition to the twofold rates of hepatitis C among men compared with women, we also found significant gender differences in patterns of hepatitis C risk behavior. Women had significantly more sexual risk behaviors than did men, whereas men had significantly more drug-related risk behaviors than did women. Overall, our data show striking gender differences in patterns and types of risk behaviors. Our data suggest that gender may modify some of the sexual risks, but the high risk of hepatitis C associated with drug use behaviors appear similar for men and women.

Male gender did not contribute independently to the risk of hepatitis C infection, whereas site, age, and needle sharing were significantly related to hepatitis C serostatus. The higher rates of hepatitis C among men can be explained primarily by lifetime exposure to injection drug use—specifically, needle sharing. The gender differences in drug risks that we observed have been reported for other populations. The findings of higher lifetime rates of illicit drug use and substance use disorders among men than among women are consistent across studies (

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21). Our analysis confirms the importance of drug-related risks, particularly needle sharing, as a component of risk for hepatitis C for both genders. Osher and colleagues (

15) provide a focused analysis of the importance and complexity of drug risks in hepatitis C transmission. The site-specific effect we observed differs from that observed by Osher and colleagues in part because of differences in the inclusion criteria.

We also observed significant gender differences in sexual risk behaviors. Compared with men, women had significantly more lifetime unprotected sex risks, including vaginal sex, anal sex, sex in exchange for drugs, and sex in exchange for money or gifts. These sexual risks do not appear to play a major role in hepatitis C transmission. However, given that there were only 24 hepatitis C-positive women in the sample, we were unable to model risks separately by gender. When we examined the specific risks in hepatitis C-positive participants who did not use needles, the suggestion of a cumulative role for multiple sexual risk factors emerged. Our results are consistent with other reports of gender differences in the rates of HIV sexual risks (

3). For example, one study of injection drug users noted that women had higher sexual risks than did men and that they engaged in behaviors that protected their partners more often than themselves (

22).

Because of the high baseline rates of sex-related risk behaviors and gender differences in patterns of risk, we were able to evaluate the relationship of sex risks to hepatitis C serostatus and compare these risks between men and women. In the bivariate analysis, several sexual risks were significantly associated with hepatitis C serostatus. These associations suggest that gender may modify several of these sexual risks. However, in the logistic regression model, sexual risk behaviors did not contribute independently to the risk of hepatitis C infection. Our results are consistent with those of a study that evaluated patients at a sexually transmitted diseases clinic (

5). The authors of that study concluded that sexual risks do not play a major role in hepatitis C transmission, although that sample was primarily male.

The results of other studies support a more prominent role of sexual transmission of hepatitis C among women (

9,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27). One study found evidence for sexual transmission of hepatitis C among HIV-infected or at-risk women in Chicago (

9). In that study, injection drug use was the strongest predictor of hepatitis C infection among women, as it was in ours, but sexual risks—history of gonorrhea or sex with an injection-drug-using partner—were also independently associated with hepatitis C infection. Another study of injection drug use among men found that 10 percent of the men's women partners (non-injection-drug users) were infected with the hepatitis C virus, suggesting that sexual transmission of hepatitis C from infected men to their female partners may occur and that women partners of men who inject drugs are at risk (

24).

Blood-to-blood contact is important for hepatitis C transmission, and there appears to be convergent evidence for sexual transmission. It has been theorized that menstruation, anal sex, and concurrent sexually transmitted diseases are all hepatitis C risk factors for women (

25,

26). This theory is especially salient for women with severe mental illness, who have high rates of sexual risk behaviors. Although sex was not the prominent mode of hepatitis C transmission in our study sample, the high rates of sexual risks that we observed among women with severe mental illness are of concern. Gender appears to modify the risk conveyed by some sexual risk behaviors. For example, for women but not men, lifetime unprotected anal sex did convey a risk of hepatitis C transmission in the stratified bivariate analysis. This gender difference may be related to which partner is receptive during anal sex. However, we did not query to obtain this information. Sexual risk behaviors are also associated with a high risk of HIV, hepatitis B, and other sexually transmitted diseases. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines on hepatitis C risk reduction recommend condom use to persons at risk of sexually transmitted diseases (

27).

Our study had several limitations. Whereas injection drug use was the single most important risk factor predicting hepatitis C seropositivity, the actual role of high-risk sex behaviors could not be ascertained in our cross-sectional study. Furthermore, there were sampling differences across sites, although we controlled for these differences in our analysis. Given the cross-sectional study design, we were able to draw correlational inferences only. Respondents may resist disclosing socially stigmatized high-risk behaviors in a personal interview. To address this possibility, our research group is currently assessing the validity of computer-assisted risk interviews among persons with severe mental illness.

Our study raises several important clinical issues for mental health care providers. First, men and women with severe mental illness have a high risk of hepatitis C. Because significant gender differences in hepatitis C risk behaviors exist, different assessment and education strategies for men and women that target the highest domains of risk may be warranted. Thus provider interventions can be informed by knowledge of hepatitis C risks and gender differences in patterns of risk.

Hepatitis C issues for women and their partners have been reviewed elsewhere (

28), and several points are especially relevant to women with severe mental illness. Our risk data suggest that spending more time educating women about sexual risk reduction may be indicated—for example, role-playing to minimize sexual risks. Other clinical issues for women with severe mental illness who are infected with the hepatitis C virus include the risks of vertical transmission (4 percent to 18 percent) and breastfeeding (probably low risk) (

29,

30). The rate of depression is twice as high among women and is a relative contraindication to hepatitis C treatment with alpha interferon. Although there have been case reports of treating hepatitis C-infected persons with a history of depression, more treatment studies need to be done (

31).

Adequate clinical time is warranted for assessing drug and alcohol risks among men with severe mental illness. Given the compelling data on risk of lifetime injection drug use and the high rates of this risk behavior among men with severe mental illness, it is also important that mental health clinicians understand and assess these risks. Further, alcohol dependence—also common among men with severe mental illness—is known to promote the progression of hepatitis C-related liver disease. Although both depression and alcohol abuse are relative contraindications to hepatitis C retroviral treatment with alpha interferon, the research in this area is minimal. A final point is that many men and women with severe mental illness take multiple medications, some of which are hepatically metabolized. The clinical implications of this for hepatitis C-infected persons—liver function and progression of liver disease—need to be evaluated.