We begin with the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's recommendations for key services for addressing the problem of elevated risk for hepatitis (

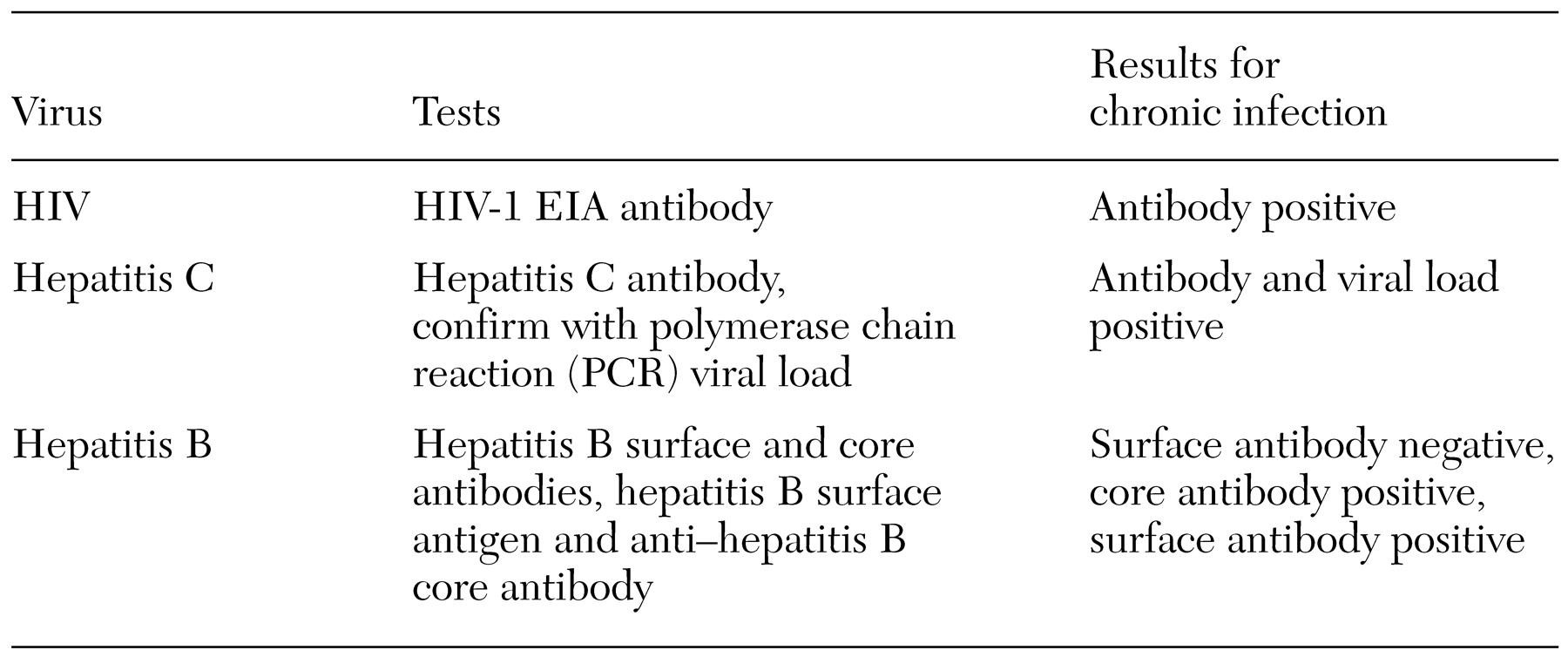

6,

7,

8,

9). These recommendations are to screen for substance use and sexual risk behaviors; to test for HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C infection; to immunize against hepatitis A and B; to provide risk-reduction counseling and substance abuse treatment; and to refer and support infected clients for medical assessment and treatment. Last we discuss the need to integrate mental health care with substance abuse treatment and with general medical care.

Immunization

Safe and effective vaccines can prevent infection with both hepatitis B and hepatitis A, which can cause fulminant hepatitis among persons infected with hepatitis B or C. Currently no vaccine exists to prevent hepatitis C or HIV infection. The vaccines for hepatitis A and B can be delivered together in one injection (

19,

20). For full immunity, three doses of the combined vaccine administered over six months are recommended. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that anyone who engages in unsafe sex or risky drug use should receive the vaccines.

If a client subsequently tests positive for hepatitis B, completing the vaccination series for hepatitis B is unnecessary. However, the vaccine series for hepatitis A should be completed, and there is no medical contraindication to completing the combined hepatitis A and B vaccine series. Persons who test positive for HIV or hepatitis C should complete the vaccination series for both hepatitis A and hepatitis B. Those who test negative for all infectious diseases but engage in risk behaviors should still complete the immunization series.

Experts believe that drug users in the general population are difficult to vaccinate because they are hard to access, and studies of adherence to vaccination among intravenous drug users have had mixed results (

21,

22). However, experience with patients who have severe mental illnesses suggests that compliance with vaccination is more likely to be achieved if immunization is integrated with standard case management and offered on-site at the usual source of care for these clients. An investigation currently under way in New Hampshire shows that a trained community mental health nurse can effectively provide education, draw blood to test for infectious diseases, and immunize against hepatitis during a single half-hour visit to a mental health center (

23).

Risk reduction

Risk reduction refers both to helping persons who are at risk but not yet infected to reduce risk behaviors and helping those who are infected to reduce behaviors that endanger others. Empirically tested, effective approaches to risk reduction for infectious diseases usually include four to six sessions of counseling to provide information, enhance self-management skills, enhance self-efficacy, and develop social supports and reinforcement for behavior change (

24). Cognitive-behavioral HIV risk-reduction groups have been developed or adapted specifically for persons with severe mental illness and have demonstrated efficacy in controlled clinical trials (

25,

26,

27,

28). It is important to note that most existing interventions do not target drug-risk behaviors and are therefore not likely to have an impact on the more prevalent problem of hepatitis C, which is most commonly spread through drug-risk behaviors. Integrated treatment for co-occurring substance use disorders and mental illness may be a more direct intervention to reduce the risk of hepatitis C.

Given the current evidence, mental health clinicians should begin by providing clients with individual counseling to help them develop motivation and skills to reduce HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C risk behaviors. Understanding the dangers of these infectious diseases may help clients become interested in learning how to avoid using drugs, but information alone is usually not enough. Studies of integrated treatment for dual diagnoses (severe mental illness and a comorbid substance use disorder) show that clients are more likely to change drug use behaviors if they find safe housing, have relationships with clean and sober friends, engage in meaningful daytime activities, and receive regular counseling and case management (

29,

30).

Medical evaluation and treatment

If a client tests positive for one of these blood-borne infectious diseases, the client needs to be referred for medical evaluation by a medical specialist or specialty team. Treatment of HIV infection is now recommended for nearly all infected persons. Treatment of hepatitis C and hepatitis B with medication may be recommended for persons with a moderately severe infection as assessed by examination, laboratory tests, and, in some cases, liver biopsy. Infected persons, even if they are not receiving treatment, should be followed yearly by a medical specialist.

HIV treatment. Antiretroviral treatment of patients infected with HIV is a rapidly evolving field. Many aspects of antiretroviral therapy have been incorporated into treatment guidelines (

31) used by HIV specialists.

Highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) is now recommended for patients who are symptomatic from HIV infection or whose laboratory examinations indicate a compromised immune system (for example, CD-4 counts). Typical first-line HAART regimens include three antiviral medications. The primary goal is to completely suppress viral replication, resulting in reduction of HIV viral load in serum to undetectable levels over a period of months. The second goal is subsequent immune restoration as the CD-4 count increases over a period of months to years. The most important predictor of long-term efficacy with HAART is the patient's adherence to the prescribed regimen.

Treatment of hepatitis B or C. The standard of care for the antiviral treatment of hepatitis B and hepatitis C—both whom to treat and with what medication regimen—is rapidly changing. The current standard for the treatment of hepatitis B infection is with either subcutaneous alpha-interferon or oral lamivudine over six to 12 months. The current standard for the treatment of hepatitis C is the pegylated version of alpha-interferon, administered as a weekly subcutaneous injection, in combination with ribavirin, administered orally in tablet form twice a day. This treatment is currently the most effective—approximately 50 percent of patients experience eradication of all virus (30 percent to 70 percent, depending on patient and viral characteristics) (

32,

33,

34).

The most common adverse events observed with interferon include fever, nausea, and injection-site reaction; the most severe are blood dyscrasias. The side effects are more likely to occur with high dosages of medication and longer duration of treatment, and they resolve rapidly when the medication is discontinued. Patients are more likely to respond to treatment if their liver disease is less severe, they have lower amounts of virus in their blood, they abstain from alcohol, and they are infected with viral subtypes other than hepatitis C subtype 1b.

Adverse effects. Clinicians have been reluctant to prescribe interferon to persons with severe mental illness and hepatitis B or C infection because of concerns about potential psychiatric and cognitive side effects (depression and memory loss) as well as questions about the ability of these patients to withstand other common side effects, including flu-like symptoms, fatigue, and malaise (

35). Currently, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends treatment for clients with severe mental illness if their illness is stabilized or in full remission (

36).

Studies of the use of antiviral medications among persons with psychiatric disorders have had mixed results regarding the prevalence and tolerance of psychiatric side effects (

37,

38,

39). Antidepressants, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclics, effectively prevent interferon-related depression and cognitive slowing in many cases but have not been studied among persons with severe mental illness (

40). However, the feasibility and safety of treating these clients with antiviral medications such as interferon in the context of careful symptom monitoring have been demonstrated (

41). Hauser and colleagues (

40) reported that they achieved high rates of hepatitis treatment adherence in a psychiatrically impaired group by using a more assertive approach to psychiatric management, including optimization of psychiatric treatment before initiating interferon, close monitoring, and adjustment of psychiatric medication to address the psychiatric side effects of antiviral medications.

Medication interactions. Prescribers of psychotropic medications need to be aware of the potential for interactions between medications used to treat infectious diseases and those used to treat psychiatric illness. The interactions of concern for treating persons who are taking medication for HIV are summarized in the recent American Psychiatric Association's Practice Guidelines for Treatment of Patients with HIV/AIDS (

42). Clinicians should refer to the APA guidelines at www.psych.org/clin_res/hivaids32001.cfm. Guidelines are also summarized elsewhere (

43).

Treatment adherence. Persons with dual disorders can be difficult to engage and retain in treatment (

44,

45,

46) and may have difficulty with medication adherence (

47). However, Walkup and colleagues (

48) found that HIV-infected persons with schizophrenia and affective psychoses were as likely to be enrolled in treatment with HIV antiretrovirals as other HIV-infected persons and were adherent to antiretrovirals for longer periods than those without schizophrenia. Given that HIV treatment is as complex and burdensome as treatment for hepatitis C infection, the results of this study suggest that persons with severe mental illness should be able to participate in hepatitis treatment.

Financing. Given the high cost of illness burden and treatment of hepatitis B and C, hepatitis screening and vaccination programs for high-risk groups make sense (

49) and are recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (

50). Persons with severe mental illness are usually entitled to and have Medicaid insurance, which can pay for tests and vaccinations, which cost approximately $80 and $90, respectively. No studies of cost-effectiveness of screening and testing have been published for persons with severe mental illness, but given the high rates of hepatitis, prevention programs could be cost-effective compared with the cost of care and treatment of persons who develop chronic hepatitis. Although treatment of hepatitis C infection with medications is costly, treatment of the illness and its complications over the longer term is also costly. Studies that model treatment of persons with hepatitis C in the general population by using interferon-alpha alone and in combination with ribavirin indicate that the treatment is cost-effective from a societal perspective (

51,

52).