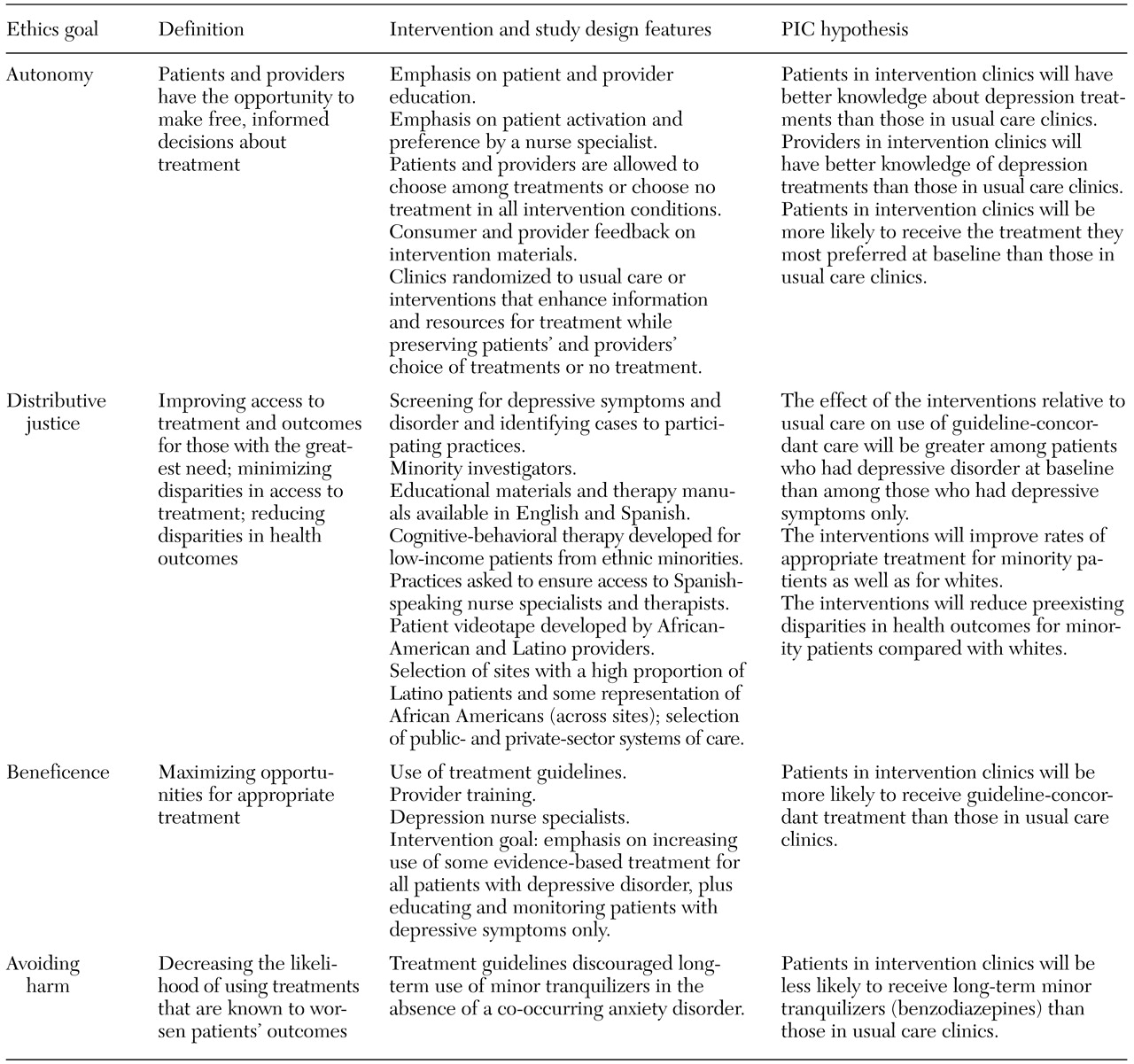

The four ethics goals, the intervention and study design modifications, and key hypotheses are outlined in

Table 1. Ethics outcome measures and summaries of published findings are shown in

Table 2. Below we briefly describe the study framework and highlight key points from the two tables.

Autonomy and respect for persons

The concept of autonomy, or self-rule, is often applied narrowly in medicine to a single encounter in which a patient gives adequately informed consent—or refusal—free from paternalistic interference. This emphasis on noninterference ignores the advocacy efforts by providers that may be needed to ensure exercise of autonomy by populations whose self-advocacy is limited—for example, because of cognitive deficits during depression. Furthermore, a broader conception of respect for autonomy is needed to respond to patients' needs, not only the need to give informed consent at one moment in time but also the need to receive types of treatment that promote their own life goals over time (

34,

35).

We approached autonomy from a systems perspective. Patients' options depend on physicians' knowledge and attitudes, and findings from focus groups suggested that some managed care physicians tended not to offer psychotherapy, because they perceived it as less effective and less accessible than medication. We therefore thought that optimal practice culture should educate both physicians and patients to support alternative, effective treatments (different evidence-based medications and psychotherapies) and ongoing access to information about their costs and benefits.

Interventions. The interventions for the autonomy goal were designed to facilitate informed choice and genuine treatment options over time for patients and clinicians: patients and clinicians had full choice over treatment (including the option of no treatment), and practices could modify the interventions to fit their priorities and resources. The nurse specialists, through their communication activities and education toolkits for patients, enabled informed choice over time. Clinician training materials also encouraged attention to patients' preferences (

Table 1).

Study design and measures. The interventions randomly assigned clinics to information and resources that encouraged appropriate care rather than to treatments. To measure patients' treatment preferences and patients' and providers' knowledge, survey items were added at baseline and at six-month patient follow-up and 18-month provider follow-up.

Hypotheses and findings. We hypothesized that the interventions would improve patients' and providers' knowledge about treatment and increase the proportion of patients receiving the treatment that they initially preferred (

Table 1). The intervention involving therapy was associated with a significant increase in patients' knowledge (t=2, df=998, p=.05; a similar trend was observed for the pooled interventions (p=.056). (These are previously unreported results.) In addition, the results showed that the combined quality improvement interventions improved clinicians' knowledge about counseling and tended to improve overall knowledge (

36). Furthermore, the interventions increased the proportion of patients at six and 12 months who received the treatment that they had preferred at baseline, relative to the patients who received usual care (

37).

Distributive justice

Our working assumption was that explicit attention to justice is needed in designing quality improvement interventions, because individuals from underserved ethnic minority groups are likely to face ongoing societal barriers when attempting to obtain better care. Furthermore, interventions based on practice guidelines that have been formulated for the average patient may lead to insufficient attention being given to the particular needs of the sickest or more complex patients, such as those with suicidal ideation.

PIC's approach to the distributive justice goal was influenced by the work of Rawls (

38). From this perspective, it is unfair to allow people to be saddled with disadvantages that are not the result of their own choices and that prevent them from meeting their basic needs when such an outcome is preventable. Thus far, thinkers such as Daniels (

39) have applied Rawlsian ideas to health care by using a definition of need based on severity of illness and functional limitations. We expand this conception to include a focus on disparities that reflect historical and current disadvantage (

17,

40).

Intervention. Practice administrators were encouraged to develop methods to facilitate access, particularly to psychotherapy, among patients from ethnic minority groups. When available, quality improvement components were selected that had been evaluated among low-income minority patients—for example, cognitive-behavioral therapy (

41,

42). Examples of modifications made by the practices include increasing the number of bilingual nurses or therapists, having therapy sessions in primary care settings, or conducting therapy by telephone. The expert leader, intervention staff, and clinician training materials included suggestions for addressing needs of sicker and more complex patients. The therapy intervention included a form of cognitive-behavioral therapy (four sessions) that was tailored to patients with minor depression. Practice therapists preferred having something to offer such patients. This modification was based on evidence that cognitive-behavioral therapy in minor depression may reduce symptoms of depression (

43) and that individual components of cognitive-behavioral therapy may be as effective as full cognitive-behavioral therapy (

44).

Study design and measures. PIC included a large number of Latino persons (primarily Mexican Americans), who constituted about a third of the sample, and included one public-sector organization with uninsured patients. The costs of modifying study materials for Spanish-speaking patients were equivalent to about half the (marginal) implementation costs of adding one site to the study, or $100,000. All surveys were field tested in Spanish and English, type fonts were enlarged for elderly patients, telephone assistance was available, and patients with hearing or other impairments could participate through in-person interviews in a location of their choice. The study included patients who at baseline had had current depressive symptoms and depressive disorder within the previous 12 months as well as those who had had current depressive symptoms without disorder within the previous 12 months. These patients were included to determine how practices prioritized the care of sicker patients and because the interventions were designed to facilitate management of a group of patients who were at high risk of developing depressive disorder, which included tracking patients who had symptoms only to watch for early evidence of disorder and to initiate treatment. No special measures were necessary to examine these outcomes.

Hypotheses and findings. We formulated three hypotheses about equity goals, which are listed in

Table 1. First, we hypothesized that the benefits of quality improvement, in terms of improved quality of care and outcomes, would extend to and include Latinos and African Americans. We found that quality of care improved in all ethnic groups, with a greater gain in clinical outcomes in the first follow-up year under quality improvement for these minority groups relative to white persons. Benefits in the area of employment were significant among whites; a similar trend was found among the minority groups, but the statistical power to detect this effect was low, and the finding was not significant (

45).

The second hypothesis was that the interventions would reduce disparities in health outcomes between white patients and patients from ethnic minority groups (

17). We found that under usual care, African-American and Latino persons had worse outcomes than white persons in the first year but that this disparity was reduced for participants in clinics with the quality improvement initiatives (

45).

Our third hypothesis was that the quality improvement interventions would be associated with greater improvements in quality of care among sicker patients who initially had depressive disorder than among patients who had only depressive symptoms. We found that in the first six months, the effects of the intervention on quality of care and health outcomes were stronger among patients who had had depressive disorder for the previous year at baseline than among those who had depressive symptoms without disorder. However, by the 12-month follow-up, the effects associated with the quality improvement interventions were comparable. Thus sicker patients initially were given higher priority for treatments. After the first six months, more equal outcome effects by baseline disorder status could reflect greater initial improvement among persons with a disorder and progression to a disorder among some of the patients who initially had only symptoms.

Beneficence

Beneficence refers to the positive duty of fiduciaries to benefit each person whom they are entrusted to serve and to the utilitarian goal of optimizing outcomes for a population (

46). The former use of beneficence reflects an individual client perspective that may resonate with practice goals of individual clinicians but that is easy to overlook when such programs are implemented in the context of practice strategies to contain rising costs. In this respect, the latter use of beneficence in reference populations is likely to be the perspective that guides outcome goals related to quality improvement at the practice administrator level. The study focused on improving average outcomes while expanding benefits to specific vulnerable populations but respected the right of practices to serve patients according to their cultural norms and resources. From an ethics perspective, this approach represents a compromise. However, it facilitated a separate scientific study goal of evaluating the impact of quality improvement interventions as naturalistically implemented by practices.

Interventions. For the beneficence goal, the interventions provided information and resources to facilitate the recognition and assessment of depression and to increase appropriate treatment (

31,

32).

Hypotheses and findings. As we hypothesized, the interventions were associated with improvements in quality of care and mental-health-related outcomes and with an increase in the proportion of patients who were employed (

33). Improved health outcomes persisted into the second follow-up year for patients in the therapy intervention, and benefits in the area of employment continued into the second year for both interventions. Higher use of antidepressant medication continued into the second follow-up year for patients who received the medication intervention (

47,

48,

49,

50).

Avoiding harm

Nonmaleficence is neither absolute nor independent of beneficence. Many medical procedures involve minor harm in producing larger benefits. Furthermore, interventions that aim to maximize cost-effectiveness may conflict with interventions that seek to protect each individual patient from harm. We did not face this conflict in PIC, because our interventions sought to reduce harm by reducing the use of minor tranquilizers in the absence of comorbid anxiety, and this was also expected to improve cost-effectiveness (

5,

15).

Intervention features. Our quality improvement manual for clinicians specifically recommended avoidance of long-term minor tranquilizers in the absence of comorbid anxiety disorder. In the medication intervention, the nurse specialist reinforced this recommendation through follow-up (

Table 2).

Study design and measures. No special modifications were necessary other than collecting information about the long-term use of minor tranquilizers in each follow-up survey and assessing comorbid anxiety at baseline.

Hypothesis and findings. As we hypothesized, the medication intervention tended to be associated with lower use of long-term minor tranquilizers, especially at two years, compared with the therapy intervention and usual care (

49).