Recent advances in medicine have greatly improved our capacity to treat major depressive disorder with drugs that are safer and more effective. The dramatic increase in new information and in the number of available antidepressants in the past decade have created a need to provide psychiatrists and primary care physicians with timely access to information about these new drugs (

1,

2). Because treatment guidelines can improve patient outcomes, methods for expanding the use of guidelines represent an important step in improving depression care. Extensive evidence has highlighted the difficulties encountered in implementing paper-and-pencil guidelines and algorithms. Fortunately, many studies have shown that these constraints can be overcome through the use of computerized systems, resulting in improved physician use and patient outcomes (

3).

In 1999 health care experts from Europe and the United States met to confront the well-documented challenges to the implementation of guidelines and to identify strategies for improvement. They recommended a multifaceted approach to improving care—in particular, designing systems that facilitate change rather than attempting to impose change on physicians' behavior (

4).

One approach is to design practice guidelines that can be incorporated into the workflow as an integral part of operations in the form of computerized decision support systems. A growing body of research indicates that physicians' use and adherence to guidelines are improved when the guidelines are furnished in a computerized format (

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11). Computerized decision support systems and computer information systems currently being used in medicine have indeed been associated with improved outcomes.

In recognition of the fact that optimal treatment of depression has been difficult to accomplish, we developed a computerized prompting and decision support system (

12). In this article we briefly discuss methods previously used to enhance the use of evidence-based treatment and information technology in medical practice in general and illustrate our prototype for use by psychiatrists and primary care physicians in the treatment of depression.

Benefits of computerized decision support systems

In the following sections we discuss the benefits of some of the decision support systems designed to address specific areas of patient care.

Diagnosis

A recent study by Rollman and colleagues (

13) examined the results of an electronic medical record (EMR) system in a primary care setting that provided electronic feedback to physicians in the diagnosis of depression. Primary care physicians who agreed with the diagnosis provided by the EMR feedback (65 percent of 186 physicians) were more likely to document the diagnosis of depression, to start the patient on antidepressant therapy, or to provide a referral to a mental health specialist. According to these authors, the EMR offered a way to disseminate current clinical practice guidelines and to direct the use of clinical practice guidelines by primary care physicians. However, in a later study, Rollman and associates (

14) found that this EMR was not associated with improved patient outcomes.

Treatment decision support

Computerized decision support systems have been shown to be particularly useful for the purposes of prescribing medication, which is the most common intervention in medicine (

15). This usefulness has been illustrated in studies showing improved anticoagulation therapy (

16,

17,

18,

19), improved antibiotic use and reduced adverse drug events (

20,

21,

22), and improved dosing (

7,

23). For example, a meta-analysis of computer support by Walton and colleagues (

23) showed a reduction in the time to reach therapeutic control (even when total drug use was unchanged) and a lower incidence of negative side effects when a computerized system was used.

Other benefits

Several studies have indicated that computerized decision support systems are useful in other aspects of health care delivery. These areas include follow-up and preventive care (

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29), computerized physician order entry and adverse drug events (

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35), and electronic documentation and information retrieval (

36).

Comprehensive systems and guideline support

Most computerized decision support systems are unidecisional tools—for example, a system that guides the timing of diagnostic tests, such as Pap smears. Some of these tools do provide assistance with treatment decisions—for example, providing advice on medication use and preventive care. A computerized decision support system that is likely to enhance clinical care for depression must incorporate and include a majority of such aspects of care into one system, providing more complete support to physicians in practice.

Tierney and colleagues (

10) have strongly suggested that computerized decision support systems should be designed to be comprehensive, not mere unidimensional tools. These authors state that guidelines need to account for comorbid conditions, concurrent drug therapy, the timing of most interventions, and follow-up. We developed a program that incorporates all the elements discussed above, because we recognized the importance of these elements (

36,

37).

CompTMAP

The computerized decision support system developed at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, called CompTMAP (after the Texas Medication Algorithm Project guidelines and algorithms), is a computerized treatment algorithm for the treatment of depression and other psychiatric illnesses and is designed for use by both psychiatrists and primary care physicians. The TMAP was a large-scale study designed to determine the clinical and economic value of using medication algorithms in combination with clinical support and a patient-family educational package in the pharmacologic management of patients with one of three major mental disorders—schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder—each compared with treatment as usual in the public mental health sector (

12).

Patients who were treated for major depressive disorder in the TMAP had better outcomes than those who received treatment as usual (

12). However, problems related to dosage, visit duration, and visit frequency were identified. In general, dosages of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors were in the range recommended by the algorithm, but oral dosages of the tricyclic antidepressants nefazodone, venlafaxine, and bupropion were lower than recommended by the algorithm. Visit frequency was less than recommended—the time between visits was close to three weeks rather than the one week recommended to ensure optimal dosage adjustments, symptom and side effect monitoring, patient education, and retention. Implementation of the algorithm was also accomplished with the help of a clinical coordinator at each of the clinics, which involved additional costs.

To address these key implementation issues, CompTMAP provides all the prompts necessary to implement the algorithm without the need for additional personnel, such as a clinical coordinator as required in the TMAP. The computerized algorithm makes it simple to follow the suggested dosage schedules and tactical recommendations by displaying the recommended dosage and treatment options for the appropriate week in treatment. All patient information, medication information, medication dosages, next appointments, and progress notes are recorded electronically and are readily accessible. Physicians using the program are given a recommended timeframe during which the patients return, which is based on the patient's stage in the algorithm. An advantage of CompTMAP is that feedback is ongoing and is available during clinic visits rather than only before or after the visits.

Features of CompTMAP

CompTMAP provides decision support in diagnosis, appropriate treatment choices, and follow-up and preventive care as well as access to physician order entry, alert systems, electronic documentation, and information retrieval.

Diagnosis

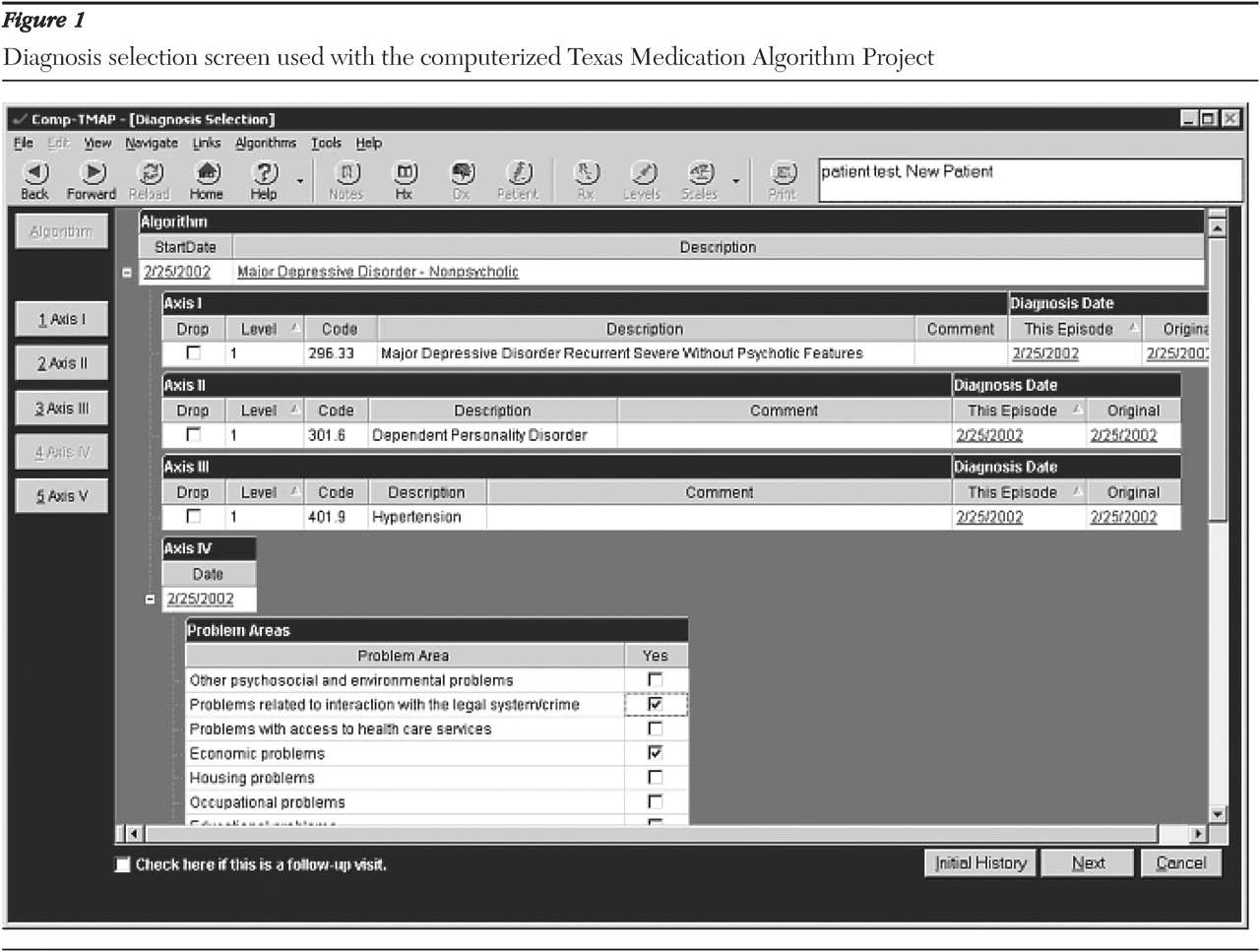

CompTMAP provides a list of major psychiatric diagnoses as categorized in

DSM-IV, as can be seen in

Figure 1. It also provides a link to the American Psychiatric Association practice guidelines that provide information about how to perform a diagnostic evaluation, although it does not provide an expert diagnostic system. The system does provide more than 15 measurement tools that can be used to help clinicians monitor symptoms and functional status over time.

Treatment decision support

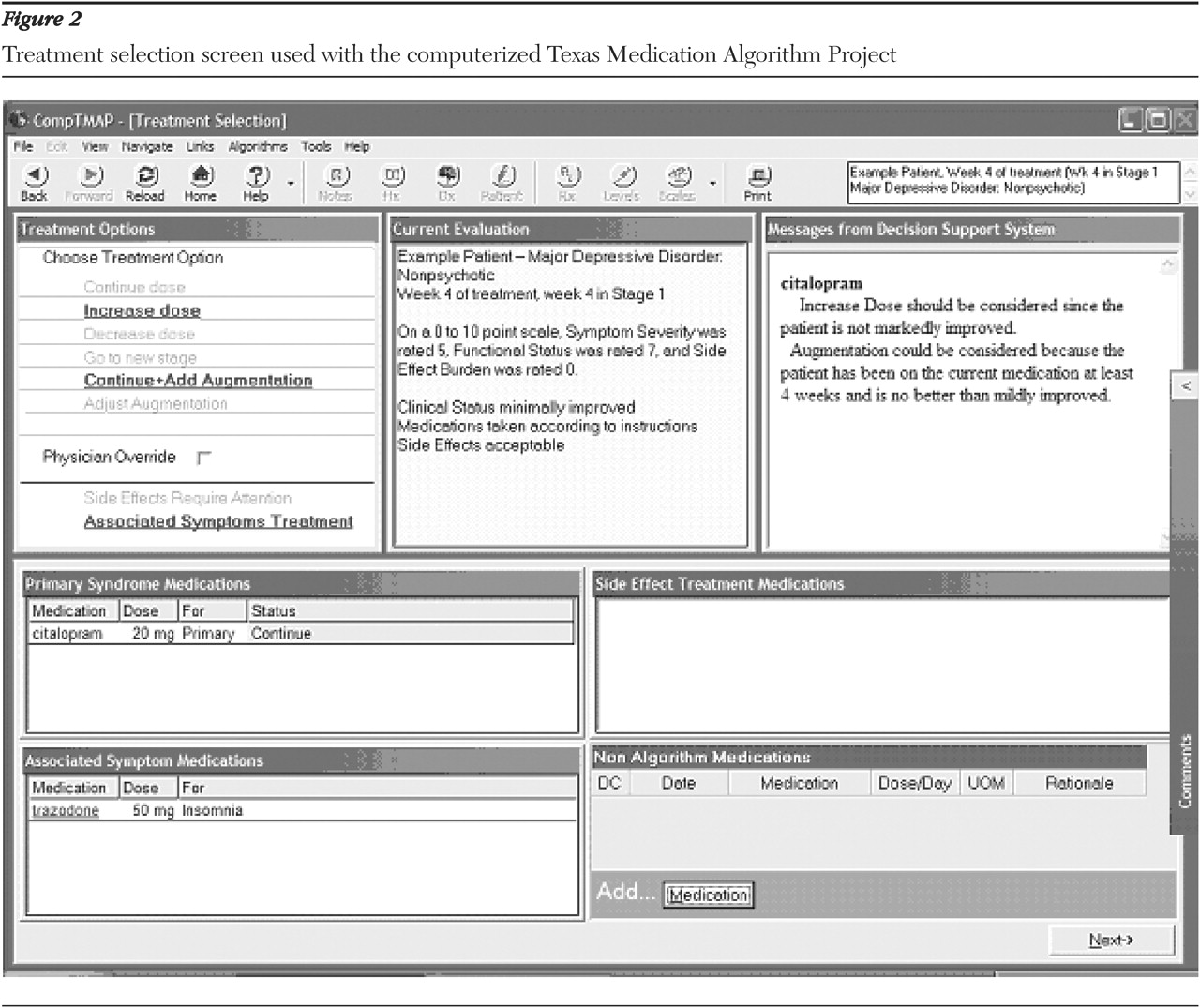

The physician obtains clinical decision support by using CompTMAP to analyze pertinent information about the patient's current clinical condition that has been entered by the physician at each visit. The patient information is integrated with the rules of the program, which are based on expert knowledge. The required information necessary for the analysis is based on three aspects of the patient's current status: compliance, response to treatment in terms of symptoms and function, and the burden of side effects. Once this information is entered, the "rules engine" of the software is invoked.

The rules engine analyzes the new information about the patient that the physician has entered, along with several other pieces of information, such as how long the patient has been receiving the current treatment, the amount of time at that dosage, and blood concentrations of the medication, if applicable. After analyzing the information, CompTMAP offers the appropriate treatment options, including dosage options, an example of which can be seen in

Figure 2. The program provides the physician with suggestions for treating with the primary and augmenting medications and also provides treatment choices for associated symptoms and side effects. Explanations and suggestions are provided in a decision support window on the same screen on which the treatment options are displayed (

Figure 2).

To ensure physician autonomy, the physician can deviate from the recommendations at any time by clicking the physician override box and providing his or her rationale for overriding the recommendation. All possible options are then enabled, and the physician can make his or her selection.

Follow-up and preventive care

CompTMAP provides reminders to physicians through screen prompts to ensure that important considerations are not overlooked. For example, if a physician prescribes a mood stabilizer, such as lithium, or some other medication that requires close monitoring of blood drug concentrations, he or she is prompted to order blood tests for that medication. The program can also recommend and display the number of weeks in which the patient should return for a visit on the basis of the patient's status and stage in the algorithm.

Physician order entry and error prevention

The physician initially chooses the psychotropic medications and dosages from pull-down menus on the treatment selection screen (

Figure 2). The selected medications then appear on the prescription screen along with the suggested route and frequency of administration. The physician can choose to adjust the frequency and type by writing specific instructions in the comments section. A prescription can be generated.

Adverse drug event alert systems

When medication errors are made, CompTMAP displays a warning box. For example, if a physician tries to order two benzodiazepines, the physician is notified that he or she has ordered two medications from the same family of medications. For medications that require blood monitoring before the dosage can safely be increased, the physician is notified that a blood reading is necessary. If a physician tries to order two medications that should not be administered together or that require caution if they are administered together, the physician is notified of the potential problem.

Documentation, record keeping, and information retrieval

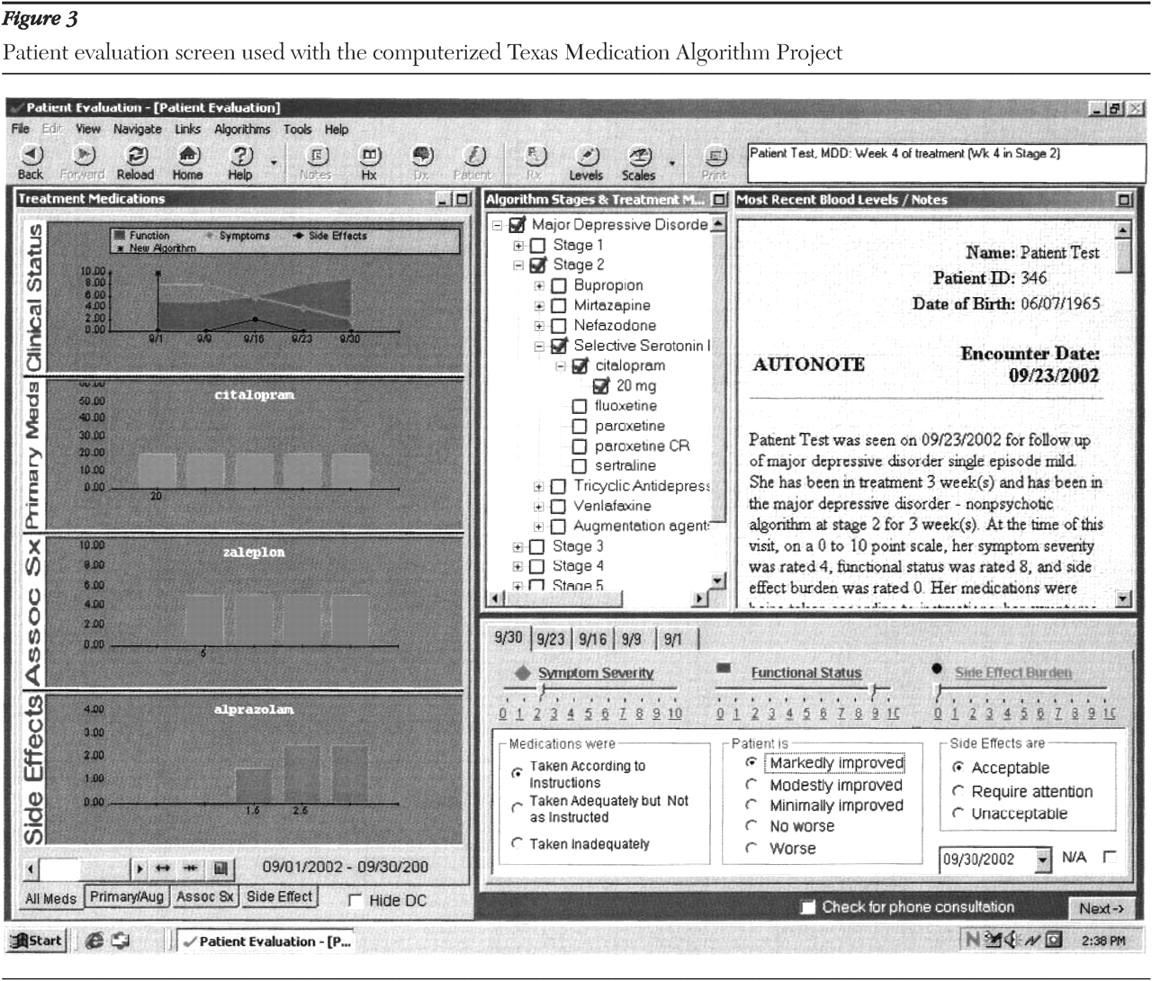

All entries are automatically stored, providing electronic documentation and record keeping. Thus the physician has ready access to complete patient information. Clinical status and prescription history are presented in easy-to-read graphs for each visit, as can be seen in

Figure 3. Additional information, such as patients' demographic characteristics, blood drug concentrations, symptom rating scale scores, and complete progress notes, is also accessible by clicking on the toolbar at the top of the screen in any section of the application.

Automatic physician notes are created and recorded as a by-product of the physician's actions during a visit without the need for the physician to type any information. Additional notes can be written as necessary. The patient's progress is recorded throughout the course of care as progress notes and is also displayed graphically to show severity of symptoms, functional status, and side effect burden over time (

Figure 3). The medication choices are also recorded in the progress notes, under prescription history, and graphically. The patient's demographic characteristics, history, physician ratings, mental status examination results, symptom scale scores, and blood drug concentrations are a part of the record. A pull-down list of CPT codes and billing processing is also available to assist in billing.

The program can be integrated into currently used clinic systems, can be interfaced to another computer application, can be used to import and export data and files, can provide online access to a main database, and can link to useful Web sites.

CompTMAP testing and physician use

CompTMAP has gone through extensive testing to ensure accuracy and reliability. Phase 1 of testing began after the computer programmers, under the guidance of the project development team, had finished entering the initial data and rules into the application and released the introductory version. This phase included testing of the program by all the professionals who worked on the project.

Phase 2 of testing involved a three-step process. Phase 2A testers were first introduced to the application and trained on its use. This select group comprised physicians and pharmacists who were considered experts in their fields and in the TMAP algorithms. The group was asked to create "test" patients, whom they entered at various stages of the algorithm and at different critical decision points in the stage with various assessments of response, adherence to medications, and side effect burden. Phase 2B involved entering actual patient chart data into CompTMAP. TMAP data were entered for 80 patients, as were chart data for 80 currently active patients in two different centers of the Texas Department of Mental Health and Mental Retardation.

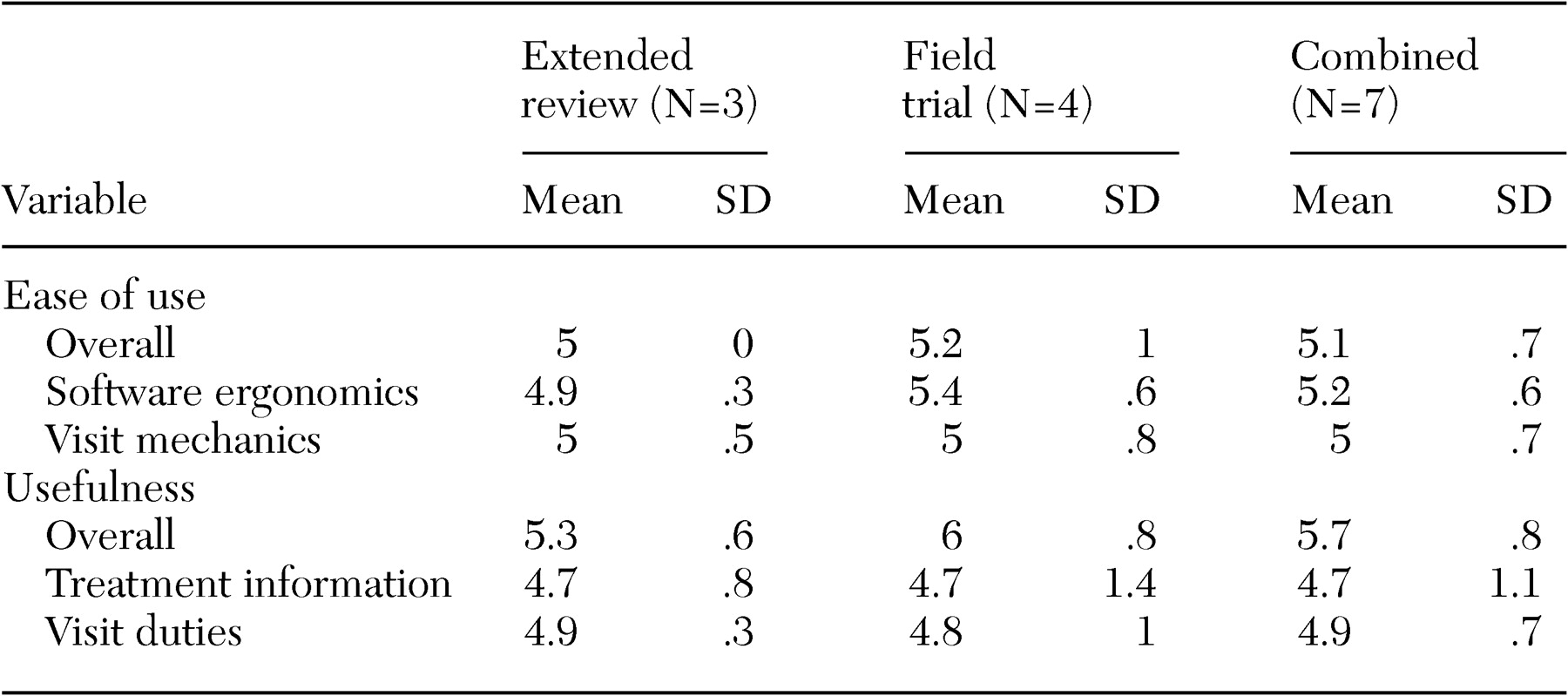

Phase 2C, the initial field-testing of CompTMAP, involved implementation of the program at two Texas public health sector sites. The first test included three psychiatrists who conducted an extended review of CompTMAP on three laptop computers. After they had been trained, these psychiatrists were allowed to use the system for two to three weeks with their patients. The second test included four psychiatrists in a field trial (at the second site). The second group then used CompTMAP with patients for four to six weeks. All seven psychiatrists were asked to complete an ease-of-use survey and a usefulness survey (

38). The psychiatrists in the field trial group reported using the software with ten to 14 patients each and for about two to four hours per week.

The Ease of Use Survey (

38) consists of 12 items that can be summarized as three scores: a global impression (one item: How easy was the software program to use?), software ergonomics (six items—for example, How easy was it for you to find what you were looking for on the screen? and How easy is it to correct mistakes?), and visit mechanics (five items—for example, How easy was the software program to use in the presence of patients? and How easy was the software program to use with your daily workflow?). All items were rated on 7-point scales, with 1 indicating not at all easy to use and 7 indicating very easy to use.

The 13 items of the Usefulness Survey (

38) can also be summarized as three scores: a global impression (one item: Overall, how useful was the software program?), treatment information (five items—for example, Did you find the treatment recommendation useful?), and visit duties (seven items—for example, How useful was the software in the prescribing of medication?). All items were rated on 7-point scales, with 1 indicating not useful at all to 7 indicating very useful.

The results of the surveys are presented in

Table 1 for both the extended review and the field trial. Although this sample was insufficient for statistical tests, all ratings were above the midpoint on the scales, indicating a positive response to CompTMAP. In general, the responses related to longer-term use (the field trial sample) were better than those related to shorter-term use (the extended review).

Conclusions

Although extensive evidence has highlighted the difficulties encountered in implementing paper-and-pencil practice guidelines and algorithms, many studies have shown that computerized systems have the potential to overcome these constraints, resulting in improved physician use and patient outcomes (

3). Depression guidelines provided in a comprehensive computerized format that can be integrated into psychiatric and primary care settings can remain a part of the process of care.

We plan to implement the computerized system in the primary care setting and in the public sector to determine factors such as the time it takes to use the system, workflow issues, accessibility issues, and patient response and outcomes. These questions are being evaluated in subsequent studies, including our ongoing effectiveness trial. We acknowledge that there are barriers to acceptance beyond a computer system's ability to be integrated into a complex organizational environment; a main barrier is physician acceptance. Barriers to acceptance of computerized programs by physicians can include physicians' knowledge of and attitudes toward computers in general. However, time constraints and the real-world usability of the program also play a role. Accordingly, recommendations from physicians who have used the program in clinical settings have been and will continue to be incorporated into the program.

CompTMAP is part of a new era of comprehensive computerized decision support systems that take advantage of advances in automation, providing more complete clinical support to physicians in clinical practice. Such advances hold the promise of enhancing quality of care for depression. These comprehensive tools have the potential to simplify and improve record keeping and to bring the most current medical treatment research to physicians in a form that they can use in their practice.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded in part through grant RO1-MH-06406201A2 (MHT) from the National Institute of Mental Health. The authors acknowledge the support of Mental Health Connections, a partnership between Dallas County Mental Health and Mental Retardation (MHMR); the department of psychiatry of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas, which receives funding from the Texas State Legislature and the Dallas County Hospital District; and the National Alliance for Research in Schizophrenia and Depression (MHT). The authors also thank the members of the CompTMAP team at Clinical Information Services: Preston Park, B.S., M.C.S.D., Michael Goodloe, M.B.A., Anne McClelland, B.S., Elizabeth Schindler, B.B.S., Hua Liang, Ph.D., Shan Sheely, B.S., Jenny Liou, B.S., Jin Fan, M.D., Jimmy Bryant, B.S., and Jay Marrow, D.V.M.