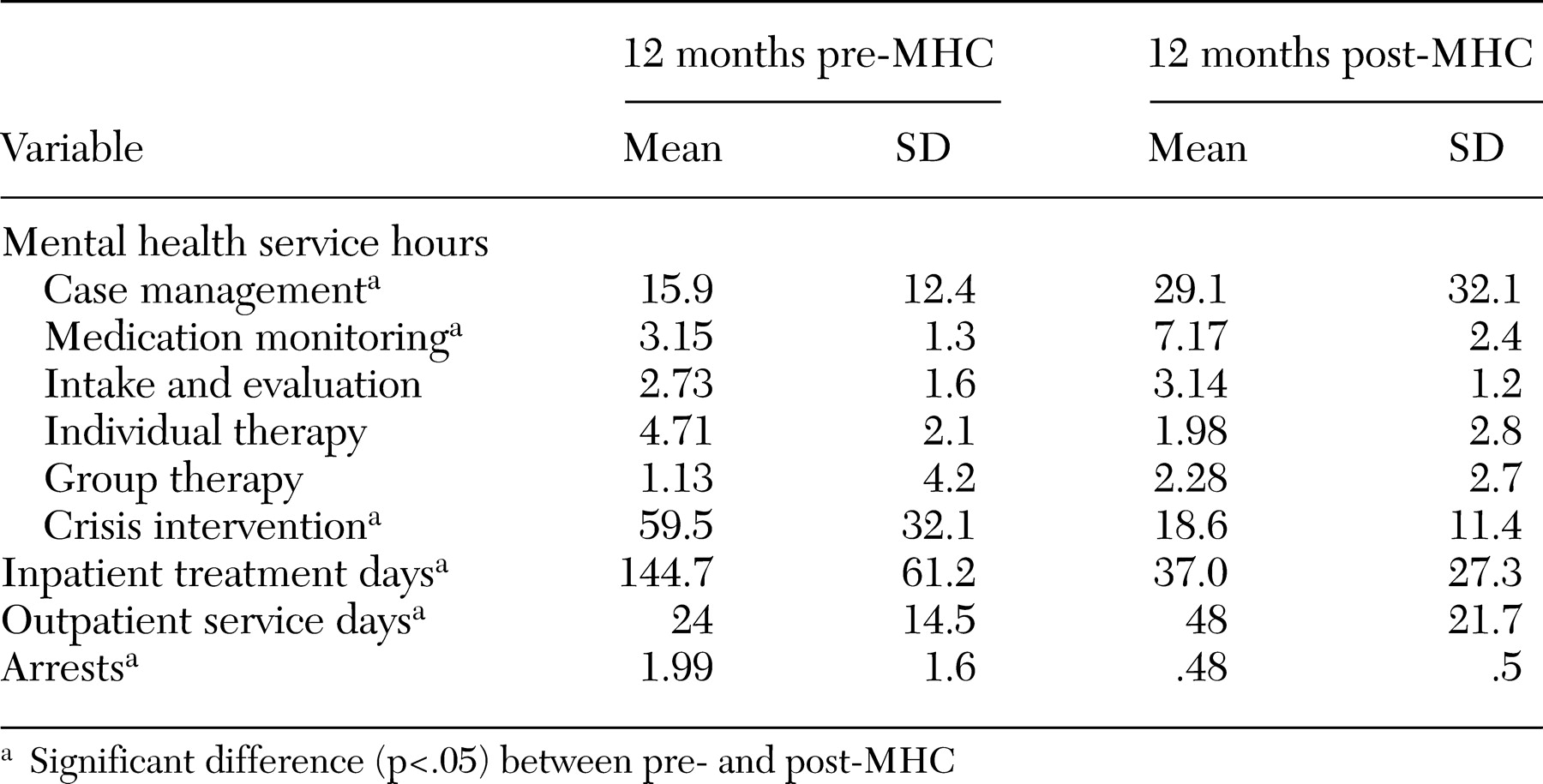

The goal of the study reported here was to address both the question of recidivism and mental health service linkage for the Clark County MHC. Specifically, the study addressed the following questions about the effectiveness of the MHC: Did MHC clients receive more comprehensive mental health services 12 months postenrollment in the MHC compared with 12 months preenrollment? Was recidivism reduced for MHC participants 12 months postenrollment compared with 12 months preenrollment? Were any client or program characteristics associated with recidivism?

To address these questions, a secondary analysis of use of mental health services and jail data for all MHC clients who were enrolled in the program since its inception in April 2000 through April 2003 was conducted. We used a 12-month pre-post comparison design to determine whether MHC participants experienced reduced rearrest rates for new offenses 12 months postenrollment in the MHC compared with 12 months preenrollment. We also examined whether MHC clients experienced fewer rearrests for probation violations postenrollment.

Methods

The Clark County Mental Health Court

The MHC in Clark County has been in operation since April 2000. In October 2001, a grant from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration funded a comprehensive study of the MHC program. The Clark County MHC shares a number of common attributes with other MHCs around the country as cited by Goldkamp and Irons-Gyunn (

1): Participation in the MHC is voluntary. There is a requirement that the defendant consent to participation. Screening and referral of defendants are completed within the first 24 hours after arrest to expedite release from jail and link to appropriate treatment. The MHC operates as a problem-solving court under the philosophy of therapeutic jurisprudence. All MHC cases are handled on a single court docket in which clients appear at regularly scheduled hearings before the MHC judge. Finally, all cases are judicially supervised to ensure compliance with structured community-based mental health treatment. A detailed description of the specific operational procedures of the Clark County MHC has been provided by Judge Randal Fritzler, the presiding judge over the MHC in Vancouver, Washington (

5).

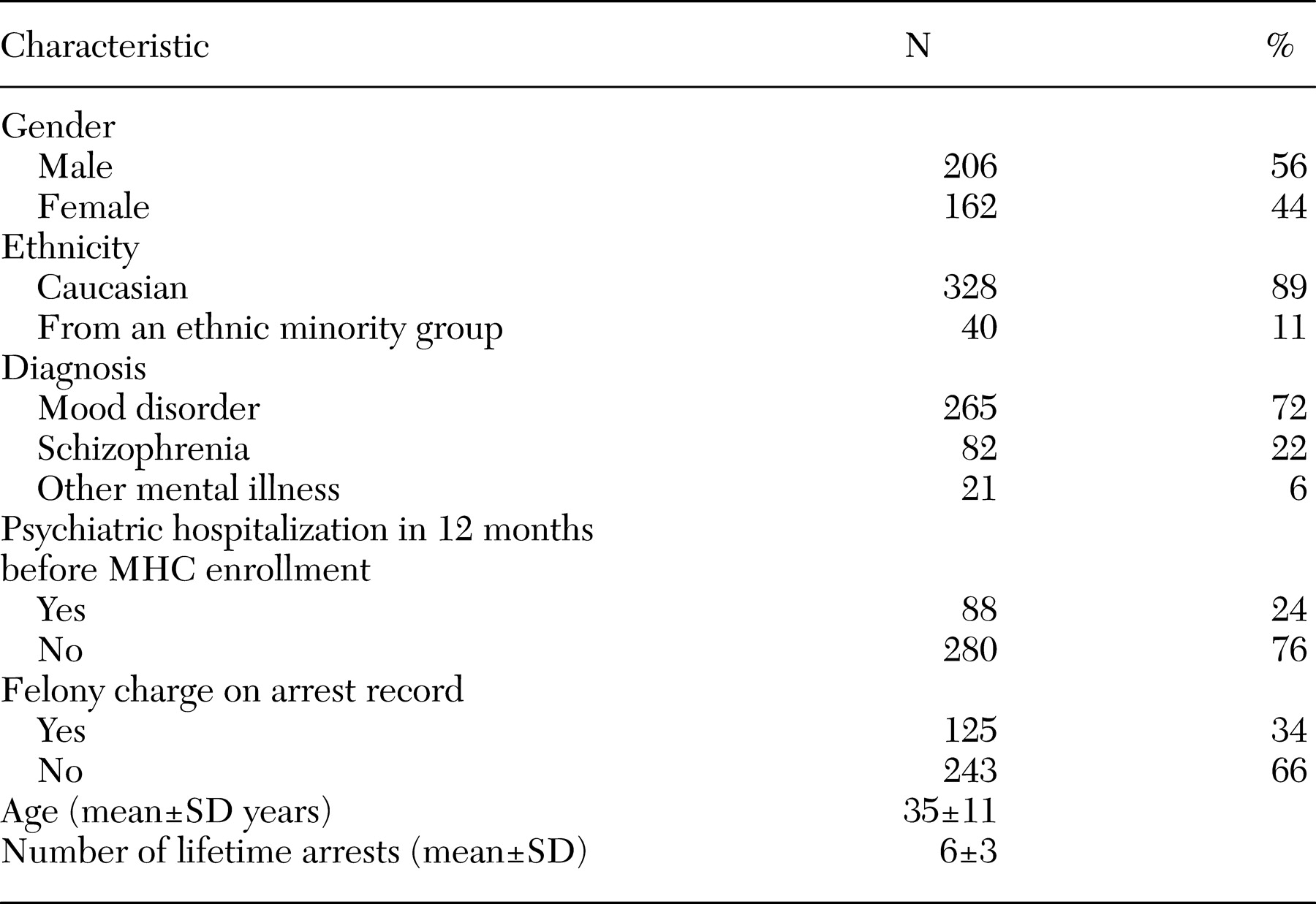

Participants

The Clark County MHC enrolled 368 mentally ill offenders between April 2000 and April 2003. The sampling frame consisted of all misdemeanants arrested and residing in Clark County, Washington. Those who met the following eligibility criteria were enrolled in the MHC: were 18 years of age or older; had been charged with a misdemeanor or a gross misdemeanor (or a felony charge that was successfully pled down to a misdemeanor); had a DSM-IV axis I diagnosis of major mental illness (schizophrenia, major affective disorder, or other diagnoses with psychotic symptoms); were able and willing to make a voluntary choice to have the case disposed in the Clark County MHC; did not have a developmental disability (for example, an IQ below 70); and did not have only an axis II personality disorder. All study procedures were approved by Portland State University's human subjects research review board.

Enrollment procedures

Mentally ill offenders entered the MHC either through a jail triage process or through a referral from the criminal justice system. In both cases, three Clark County MHC coordinators were responsible for verifying the eligibility of potential clients on the basis of the criteria detailed above. The MHC coordinators were master's-level qualified mental health professionals who had been trained to conduct mental health and drug and alcohol assessments. After the MHC assessment, MHC coordinators provided a description of the MHC program to eligible offenders and explained the post-plea nature of the court (clients must plead guilty to their charges, which are expunged upon graduation from the MHC). The MHC was initially offered on a pre-plea basis (clients could enroll in the MHC in lieu of sentencing). The program became a post-plea program in October 2001.

The client was then left to make his or her decision about enrollment before being arraigned. After enrollment, each client was referred to appropriate mental health services by his or her court coordinator, usually within 24 hours. Both the court coordinators and mental health service providers supervised clients on an ongoing basis throughout their participation in the MHC program.

Data collection

Arrest data. Booking data were provided by the Clark County Department of Community Services and Corrections for all individuals enrolled in the MHC. The corrections management information system (MIS) tracks all charges brought against an offender on the date that he or she is booked, the court case number, and the status of the offense. From these data, the number of arrests, the type of crime, the class of crime (felony versus misdemeanor), and probation variables were created.

Mental health service utilization data. Mental health services data were provided by the Clark County Regional Services Network (RSN) for all MHC clients. Variables included DSM-IV diagnosis, drug and alcohol assessment information, and mental health service use. Service use data were tracked by the RSN through daily activity logs in which service providers recorded the type of service activity, units (in 15-minute increments), and location of services provided for all clients each workday. The type of activities tracked included assessment, case management, medication management, crisis-related services, intake, employment, other outpatient services, inpatient services, and day step-down diversion from the hospital. RSN data were acquired for all MHC clients for 12 months before enrollment in the MHC and 12 months postenrollment.

For clients to be included in this study, at least 365 days since enrollment in the MHC must have accrued, so that recidivism could be measured for each participant 365 days postenrollment in the MHC compared with 365 days preenrollment. Of the 368 clients who participated in this study, 69 had successfully graduated, 222 had terminated from the project without graduation, and 77 were still enrolled in the MHC program. However, all 368 had at least 365 days past initial enrollment in the MHC. Of the 222 terminated clients, 116 (32 percent) were terminated from the MHC for noncompliance with requirements, 75 (20 percent) opted out of the program, 24 (7 percent) were transferred to another court (either a substance abuse court or a domestic violence court) because of the prevalence of domestic violence or substance abuse issues, and seven (2 percent) moved out of the district. The average number of days enrolled in the MHC for the 222 terminated clients was 161, compared with 382 days for the graduates. For the 77 enrolled clients, the average number of days in the program was 409. All clients had 365 "follow-up" days postenrollment.

Data analysis. For the purpose of our analysis, variables were conceptualized in terms of five blocks: demographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, use of mental health services, criminal history, and MHC participation. The demographic variables were age, gender, and ethnicity (white versus not white). Clinical characteristics were dummy coded into diagnosis of schizophrenia or affective disorders and were compared with other mental health disorders. Previous psychiatric inpatient treatment and alcohol or drug treatment were used as dichotomous variables. Mental health service use variables were hours of mental health service use in the 12 months before enrollment in the MHC and in the first 12 months postenrollment. Criminal history variables were the number of times booked one year preenrollment in the MHC and the highest class of crime (misdemeanor or felony) for any arrest in the past 12 months.

One-sample t tests were used to examine changes in the number of arrests and hours of mental health services used 12 months preenrollment in the MHC and 12 months postenrollment. Multivariate prediction models were fitted by using logistic regression to examine predictors of rearrest for new offenses at 12 months. Effect size was assessed with odds ratios. Statistical significance of the affect was assessed with the Wald chi square statistic. SAS was used for the statistical analyses.

Discussion

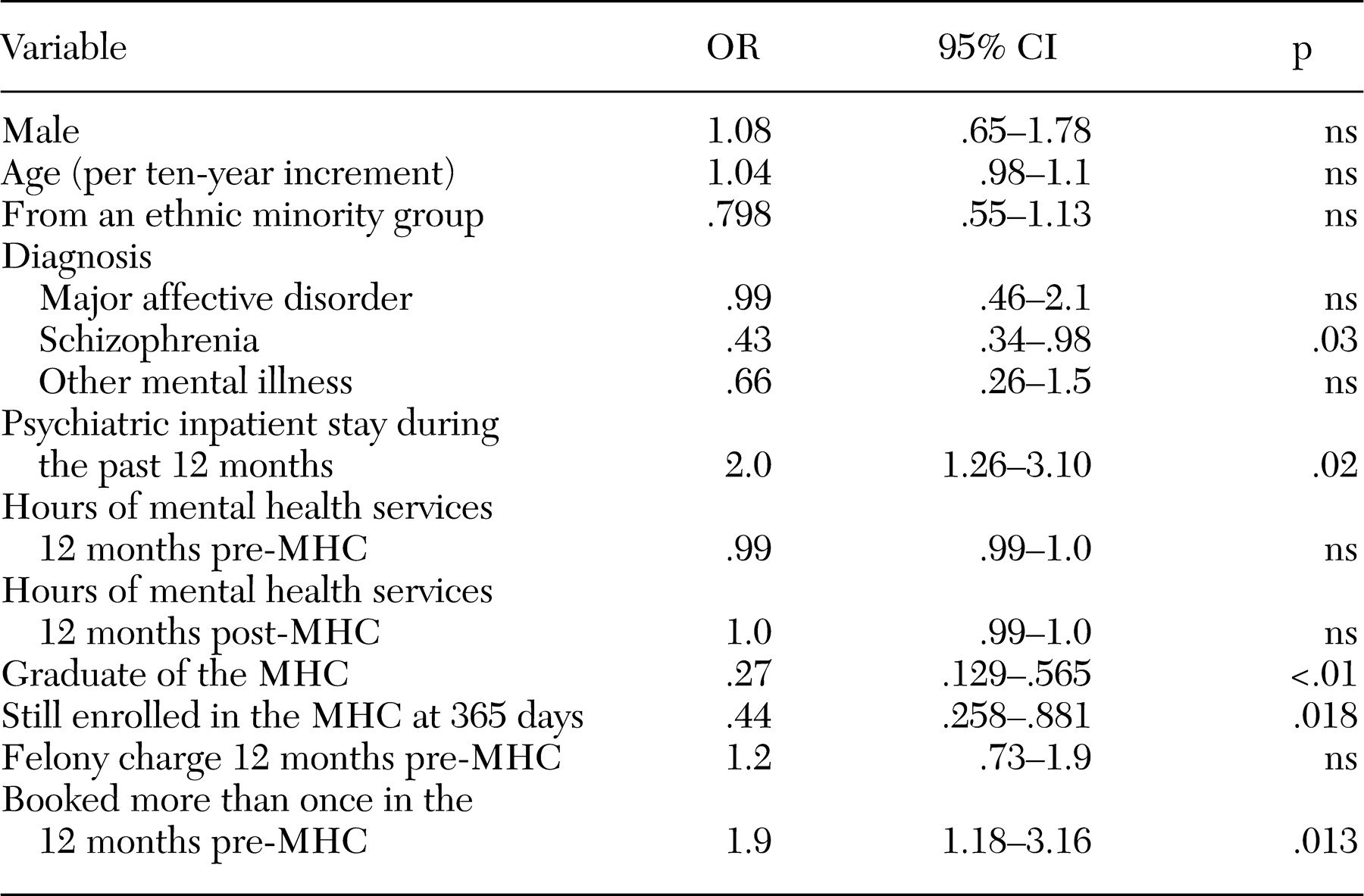

The findings of this study indicate that the MHC helps break the cycle of the repeat offender. The overall crime rate for MHC participants was reduced 400 percent one year after enrollment in the MHC compared with one year before. In addition, MHC participation was associated with a 62 percent reduction in rearrest for probation violations.

The most significant factor in determining the success of MHC participants was graduation status. MHC clients who did not graduate were 3.7 times as likely to reoffend compared with those who did graduate. It is noteworthy that the link between graduation status and rearrest remained significant after we controlled for diagnosis, prior arrest history, mental health treatment, and clients' demographic characteristics and suggests that MHC participation significantly affects the rearrest behavior of mentally ill offenders.

However, an unexpected finding was that increased intensity of mental health services measured by hours of service was not significantly associated with rearrest. A limitation of this study is that we did not have measures of key qualitative aspects of the court. However, exploratory qualitative data were collected from a subsample of 55 consumers that suggested that relationships developed between the MHC coordinator, the judge, and the consumer were critical to clients' success. In addition, at the system level, the MHC represents extensive interagency service coordination between the mental health, adult corrections, and the local consumer advocacy agency. With this cooperation, the agencies were able to reach a common consensus of how therapeutic jurisprudence would best serve mentally ill offenders in Clark County. It is likely that these qualitative aspects of the MHC contributed to reduced rearrest among MHC clients. In a future paper we intend to explore qualitative components of the MHC (client relationships and interagency collaboration). As in previous research (

6), clinical characteristics did not play a role in increasing rearrest for new criminal charges.

In another study that examined recidivism among persons with mental illness, Solomon and colleagues (

7) found that increased incarceration rates were associated with increased intensive case management. They argued that increased monitoring of behavior associated with intensive case management resulted in mental health care providers' contacting probation and parole officers about noncompliance that may in fact have initiated incarceration. However, in the study by Solomon and colleagues, there was not an MHC in operation with the explicit goal of working together to keep mentally ill offenders out of jail.

Another limitation is that it is unclear what aspect of graduation status led to reduced rearrest. It is likely that clients who opted in to the MHC and stayed for the 12 to 14 months required to graduate were more motivated to make life changes and were thus more open to high levels of supervision and intensity of services provided than those who refused participation, did not comply with MHC requirements, or opted out. Motivation to change as well as other explanatory variables that remained uncontrolled in our analysis may account for some of the association between rearrest and graduation status.

To determine whether graduation status was simply a proxy measure for time in the MHC, a separate model (not presented here) was run, in which number of days in the MHC was substituted for the two MHC status variables (graduated and still in the MHC at 365 days compared with terminated clients). However, number of days in the MHC was not found to be a significant predictor of rearrest.

We chose to include the index arrest (the conviction that brought offenders before the MHC) in the total number of arrests during the 12-month preenrollment period. We believed that, given the history of involvement with the criminal justice system in this sample, it would be arbitrary to exclude the index arrest. The average number of lifetime arrests for this sample was six (as recorded in the Clark County Department of Corrections MIS database), the number of arrests 12 months before the MHC was 1.99, and the number 24 months before the MHC was 2.4, including the index arrest. However, it could be argued that including the index arrest created an artificially inflated pre-mean in that the prearrest number must be at least one to be eligible for the MHC. A more conservative estimate would result by excluding the index arrest, which would result in a pre-mean of .99, which, compared with the post-mean of .48, still demonstrates a significant reduction in arrests (paired t=5.9, df=367, p<.001).

The past two years has seen a great deal of debate among Clark County MHC stakeholders about whether to expand the MHC to include persons with felony charges. Although the index offense for this population of 368 mentally ill offenders had to be a misdemeanor for the person to qualify for the MHC, 34 percent had prior felony charges on their records. Those with prior felony arrests were not more likely to reoffend than misdemeanants, indicating that the MHC may have a positive impact on recidivism rates if it is expanded to include those with felony offenses.

More outcome studies are needed to determine the effectiveness of MHCs. To truly assess the effectiveness of MHCs, randomized trials comparing clients served by an MHC with a control group are needed. Future research could also examine the relative effectiveness of the features of existing MHCs, such as the degree of interaction and service coordination between mental health services and the court processes, pre-plea versus post-plea enrollment criteria, felony versus misdemeanor courts, use of sanctions and threat of sanctions on client outcomes, and the role and relationship between the judge and clients.

Steadman and colleagues (

8) have stated that, in addition to future outcomes research, there is a need for a common structured model or set of operational criteria for defining an MHC. Two presiding judges of MHCs, Judge Ginger Lerner-Wren of Broward County and Judge Fritzler of Clark County, are working on documenting the key components and innovative features of MHCs (

9).