The co-occurrence of mental and substance use disorders is prevalent, costly, and a service priority for state mental health and substance abuse agencies (

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6). States are increasingly being asked to provide evidence-based services to persons with dual diagnoses and their families (

7,

8). These dual diagnosis clients include those who have serious mental illness and a substance use disorder as well as those who have an affective or anxiety disorder who do not meet formal criteria for a serious mental illness and who typically enter treatment through the substance abuse treatment system rather than the mental health system (

9,

10). Both clinicians and program administrators look to treatment guidelines and other reviews of the empirical evidence to help them decide what services to implement. Policy makers use treatment guidelines to hold the service system accountable for providing evidence-based care.

In this article we review and evaluate the literature and guidelines on care for individuals with a co-occurring affective or anxiety and substance use disorder. Our objective is to describe how standard treatment practices should be modified when delivered to persons with co-occurring disorders. We identify specific clinical recommendations and the evidence supporting each recommendation. We also discuss the comprehensiveness of the recommendations, identify gaps, and point out how some of the recommendations conflict. We hope that this paper will serve as a document that will be useful to clinicians and program administrators as well as state mental health and substance abuse agencies who want to achieve better outcomes for persons with co-occurring disorders by increasing access to and improving the delivery of evidence-based care.

Methods

We conducted MEDLINE and PsycINFO computerized searches of the English-language literature for the period 1990-2002, using the search terms "guideline*," "treatment," "algorithm," "protocol," and "parameter" plus each of the following key words: "major depression," "depression," "dysthymia," "generalized anxiety disorder," "panic disorder," "manic depression," "PTSD," "bipolar disorder," "substance*," "drug*," "alcohol," "opiate*," "cocaine," and "marijuana." We searched separately for the key words "dual diagnosis," "coexisting," "co-occurring," and "comorbid," along with the key words "substance*," "mental health," and "psych*." We supplemented these articles with searches of the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1990 to 2002) and with articles that were sent to us by experts in the field to review. Web sites for the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration were queried for each of the search strings: "treatment guidelines," "coexisting," "co-occurring," or "dual diagnosis." Bibliographies of selected papers were hand searched for additional articles. From these searches a total of 219 articles were found, of which 127 were selected for review.

Article titles and abstracts were reviewed to determine inclusion eligibility. All practice guidelines and treatment algorithms pertaining to specific affective and anxiety disorders and to substance abuse were included, as were review articles and government-sponsored consensus documents on the treatment of co-occurring disorders. Articles were excluded if they reported on results of a single program evaluation, if they did not pertain to persons with affective or anxiety disorders and substance use, or if they did not include adults.

The articles we included were abstracted into recommendation tables, which were checked and rereviewed by the research team for clarity and placement of the recommendation in the table. We abstracted the original text of the recommendation to capture important specifications and noted the populations and settings to which the recommendation applied. The tables also summarized the level of evidence behind each recommendation on the basis of four categories: recommendation supported by the results of randomized outcome studies, results of studies with quasi-experimental designs, case studies, and expert opinion. In cases in which the guideline or review article did not give enough detail on the target population or level of evidence, we went back to the original articles cited in the review.

Results and discussion

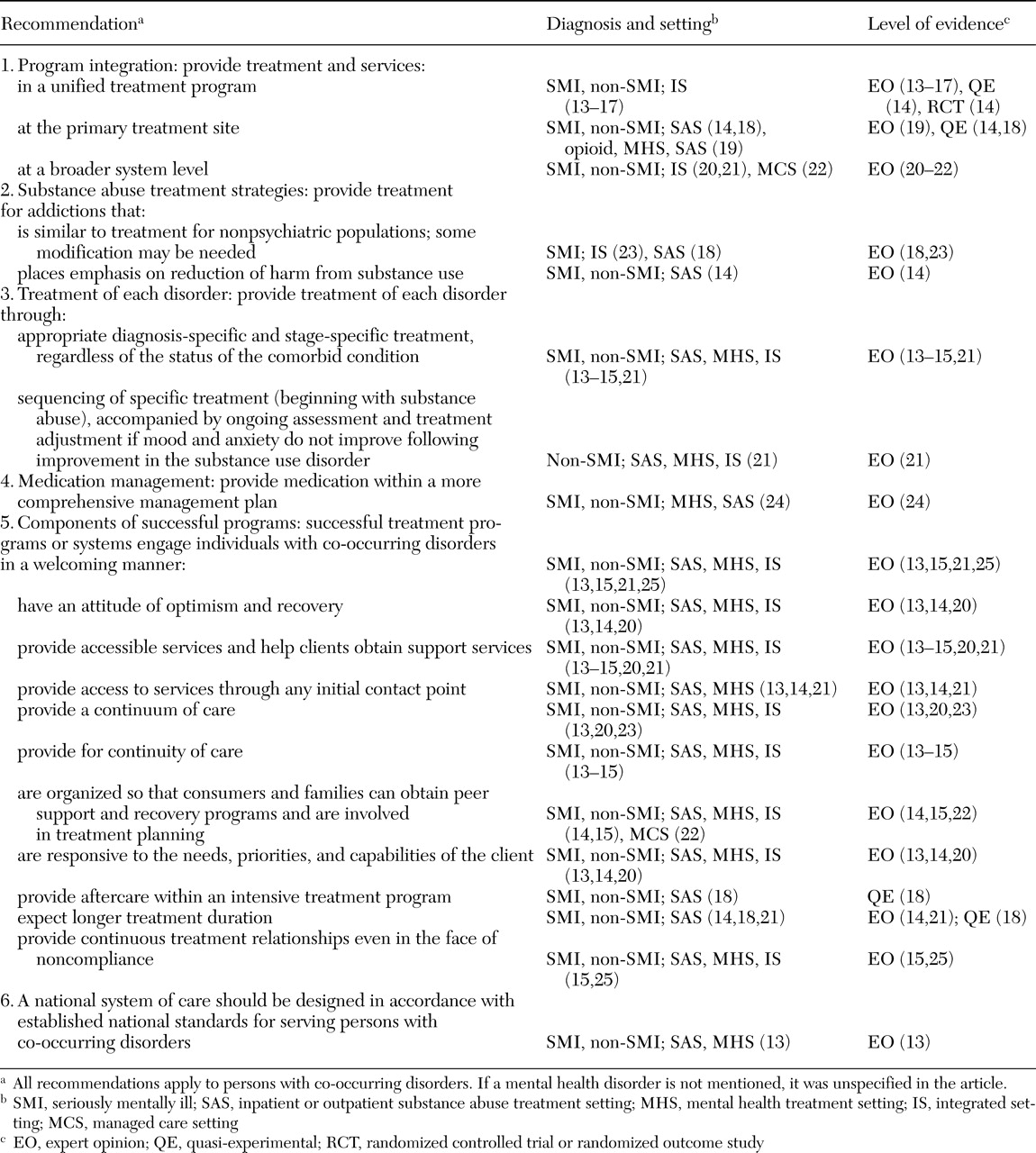

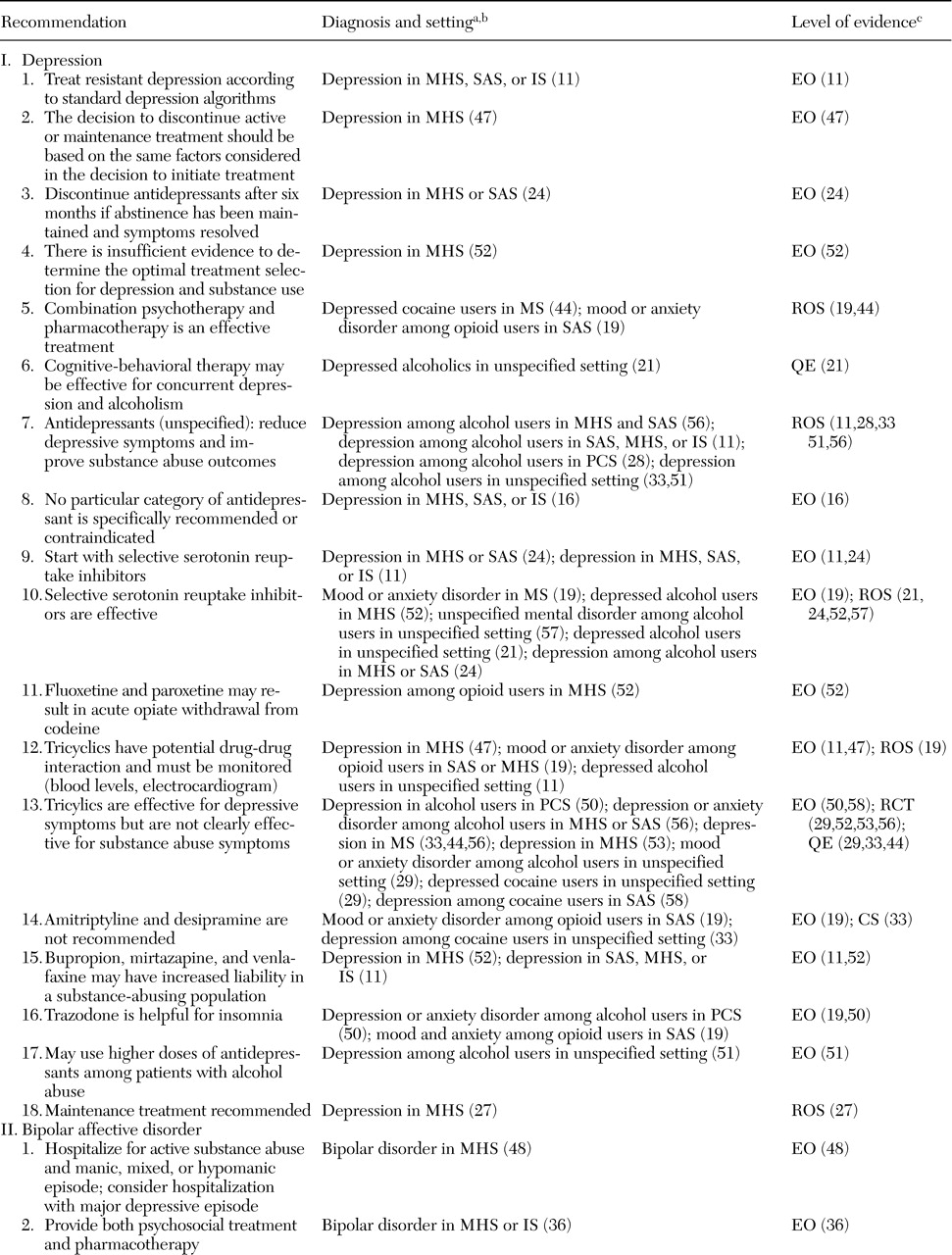

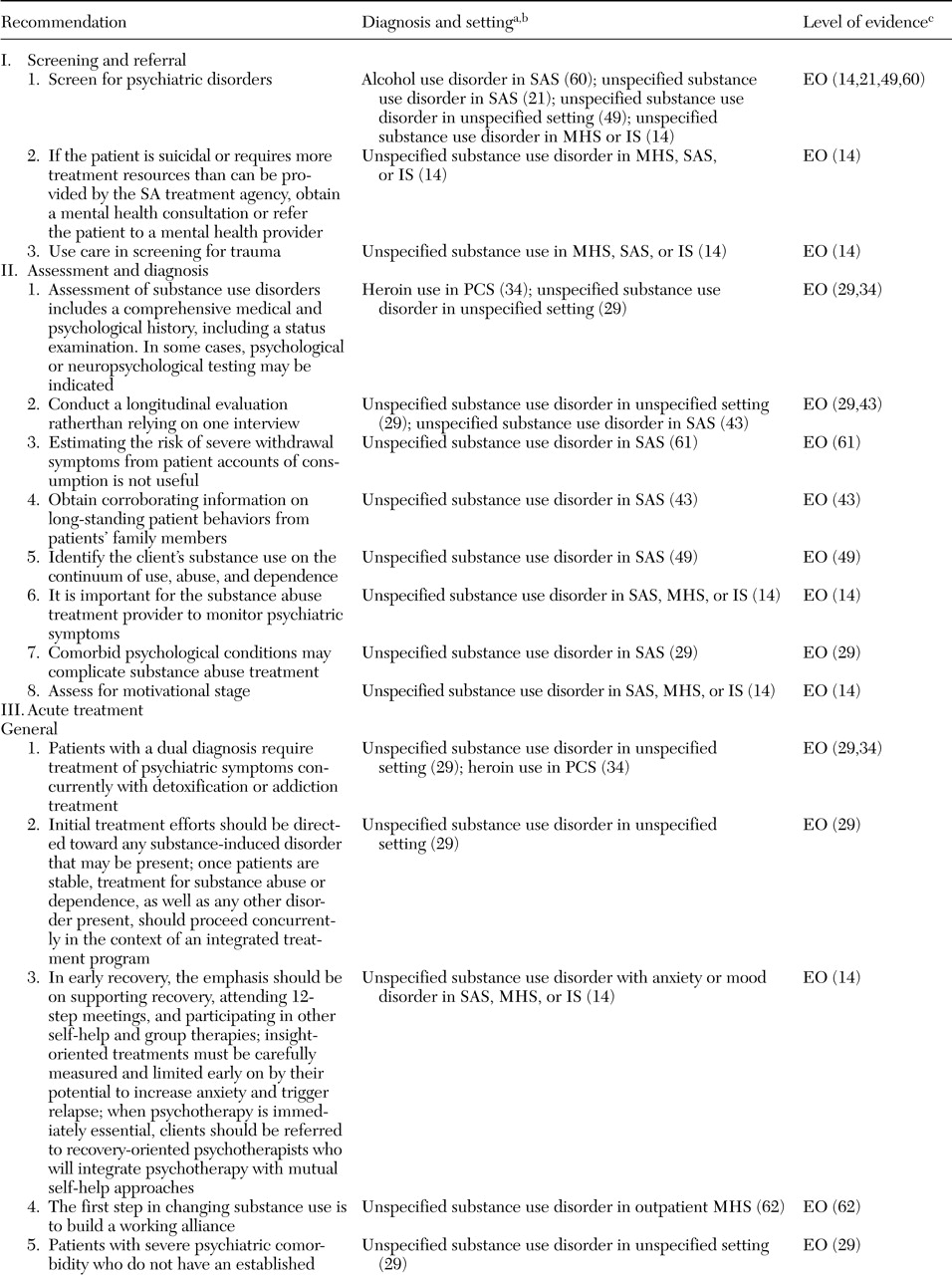

We grouped similar recommendations into three categories: program and system-level recommendations (

Table 1), general (

Table 2) and diagnosis-specific (

Table 3) mental health treatment recommendations, and substance abuse treatment recommendations (

Tables 4 and

5) (

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64). Recommendations concerning clinical care for a mental health disorder were assigned to the mental health treatment recommendations category, and those concerning care for substance abuse were assigned to the substance abuse treatment category, regardless of the treatment setting or whether it was the disorder for which the patient was in treatment.

Table 1 shows program and system-level recommendations for co-occurring disorders. Almost all of the six recommendations are supported only by expert opinion and include many precepts widely held by the field. The recommendations include integration of treatment and services, treatment provision for each disorder, and a list of successful treatment program components. A majority of the 35 recommendations in

Table 2 are supported solely by expert opinion (N=25). Only five of the recommendations are supported by the highest level of empirical rigor, a randomized outcome study, of which three involve pharmacologic intervention. The 62 recommendations in

Table 3 include some recommendations that are common to people without co-occurring disorders and some that are unique to this population. Thirty-eight of the 62 recommendations in

Table 3 are supported only by expert opinion. Thirty-two of the 36 general substance abuse recommendations included in

Table 4 are supported by expert opinion. Stronger empirical evidence is offered for some of the recommendations involving psychosocial intervention. As can be seen in

Table 5, only ten recommendations were found for specific substance use disorders (alcohol, cocaine, and opioid use); however, eight of these recommendations are supported by strong empirical evidence. Many of these recommendations involve pharmacologic intervention.

This article reviews treatment recommendations for co-occurring affective or anxiety and substance use disorders and specifies the level of evidence in support of each recommendation. We include recommendations that are in conflict to highlight where the field has not yet reached consensus or where empirical evidence is lacking. To our knowledge, this is the first review of treatment recommendations that specifically focuses on individuals with a co-occurring affective or anxiety and substance use disorder and that includes the level of evidence behind each recommendation.

Over the past several decades treatment for co-occurring disorders has undergone a broad shift in approach, from treating substance abuse before providing mental health care to providing simultaneous treatment for each disorder, regardless of the status of the comorbid condition (

13,

14,

15,

16,

1721). This shift appears to be driven by at least two factors. Although mental disorders may be the direct result of substance abuse, epidemiologic data indicate that most mental disorders temporally precede substance abuse, which suggests that they are two independent disorders and that the substance abuse is exacerbating rather than causing the mental disorder (

2,

4). A second factor has been the growing recognition that treatment approaches that focus on treating the substance abuse first have not been successful because substance use disorders tend to be episodic and recurrent. It is simply not feasible to expect acute treatment of substance use disorders to result in sustained recovery and thereby pave the way for a simpler approach to treating the mental disorder. Concurrently, there has been an increasing emphasis on psychopharmacology for the treatment of mental disorders, a shift that parallels changes occurring in the treatment of mental disorders among persons who do not have a substance use disorder.

Many treatment recommendations are supported by broad consensus. All diagnosis-specific guidelines recommend that clinicians screen for the presence of a comorbid condition. Similarly, it is broadly believed to be important to conduct a longitudinal evaluation and obtain corroborating diagnostic information from the client's friends and family. It is also recommended that clients be evaluated as to whether they have a substance-induced mental disorder or a separate axis I disorder that is causing the psychiatric symptoms and that they be educated about the side effects of medications and be given information about when they should expect symptoms to improve. All guidelines and reviews for co-occurring disorders recommend some form of "integrated" treatment.

Key issues identified by the review Recommendations lack specificity. Despite broad agreement, recommendations for the treatment of co-occurring disorders often are not specific enough to guide clinical care. For example, the intervals at which screening should occur and the instruments that should be used are not clear. Also unspecified is the level of workforce competency needed for various treatment tasks. There is no guidance on which of the competing treatments are optimal, and for which clients. This lack of clinical specificity is important, because it means that it is difficult for clinicians and administrators to implement the recommendations.

The definition of "integrated" treatment is particularly problematic. Some authors consider integrated treatment to be a unified treatment program, in which staff is cross-trained and both mental health and substance abuse treatment providers share the same treatment chart and treatment plan. (

13,

14,

15,

16,

17). Others consider co-location of mental health and substance abuse services or the provision of both types of service at the primary treatment site to be integrated treatment (

14,

18,

19). Still others consider integrated treatment to be the integration of services at a broader system level through interorganizational linkages and referrals (

20,

21,

22). The lack of a common definition or operational taxonomy that specifies the different types of integrated treatment makes it difficult for public and private payers to evaluate the appropriateness of treatments and to compare alternative approaches.

Recommendations lag behind current practices. Most recommendations that have specificity are for acute pharmacotherapy, but even specific recommendations lag behind current clinical practice. Many studies have evaluated the use of tricyclic antidepressants for populations with co-occurring disorders; fewer studies have looked at the use of newer antidepressants (

65). Yet tricyclics are rarely prescribed now that newer agents are available, so treatment recommendations concerning them are of little relevance.

Some recommendations reflect disagreement about important details. Although the use of psychotropic medication for mental illness is encouraged, experts disagree as to whether it is necessary to wait for abstinence before pharmacotherapy is started (

11,

14,

20,

25,

29,

33,

41,

42,

50). This disagreement does not vary by the specific substances being abused or by the type of mental illness. Although abstinence is the ultimate goal of substance abuse treatment for co-occurring disorders, the relative importance of harm reduction as an interim goal is unclear. These important questions are yet to be resolved.

Recommendations in diagnosis-specific guidelines do not specifically apply to persons with co-occurring disorders. Although most diagnosis-specific guidelines contain a small section documenting the importance of co-occurring disorders, diagnosis-specific guidelines are often silent as to whether the specific treatment recommendations apply to co-occurring disorders (

29,

30,

3139,

47). Thus there is no evidence for important treatment questions such as how long psychotropic medication should continue once symptoms have remitted, whether and for how long maintenance treatment for substance use or mental disorders is recommended, and whether methadone is efficacious for individuals with opiate addiction who have co-occurring disorders. In the absence of evidence, the presumption is that clinicians should use the same guidelines to treat persons with co-occurring disorders as they use to treat those with a single disorder.

Empirical evidence is lacking for most recommendations. Perhaps the most important issue revealed by our review is that empirical evidence is lacking for most recommendations. Of particular importance is the lack of evidence for the recommendation to treat patients with co-occurring disorders in integrated treatment settings, the need for specialist assessment, and the sequencing of substance abuse and mental health treatment. Most recommendations are supported by expert opinion, and there are few randomized—or even quasi-experimental—designs. When empirical evidence exists, it is usually diagnosis and setting specific, yet the recommendations we found in conducting this review are framed in more general terms. In addition, many recommendations are not easily evaluated for efficacy, such as the recommendation that successful treatment programs be welcoming and accessible and convey an attitude of optimism and recovery.

Some recommendations are supported by empirical evidence, including the recommendation to screen for substance abuse (

27) and the effectiveness of specific treatments for depression and anxiety disorders (

11,

19,

21,

24,

27,

28,

2932,

33,

36,

41,

4446,

49,

50,

51,

5256,

57) and for substance abuse (

21,

28,

29,

41,

4452,

58,

63,

64).