The report of the President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health has renewed attention to programs designed to reduce unnecessary institutionalization and promote community living. Spending for different types of care provides one important indicator of states' support of such programs. Traditionally, the primary source of such information has been from the budgets of state mental health agencies. In fiscal year 2002 two-thirds of spending by state mental health agencies went to community mental health services, with 30 percent going to state mental hospitals (

1).

Increasingly though, such budget data provide only a partial picture of states' mental health spending. For example, mental health agency data do not usually include spending by other agencies or spending for mental health services provided by nonspecialty providers.

A broader picture of total spending by states on mental health services can be derived from estimates of national spending for mental health and substance abuse services (

2). One feature of these estimates is the calculation of payment for mental health services by major payer categories. Two of these categories—Medicaid and other state and local government funding—make up most of the spending for mental health services that states and localities administer.

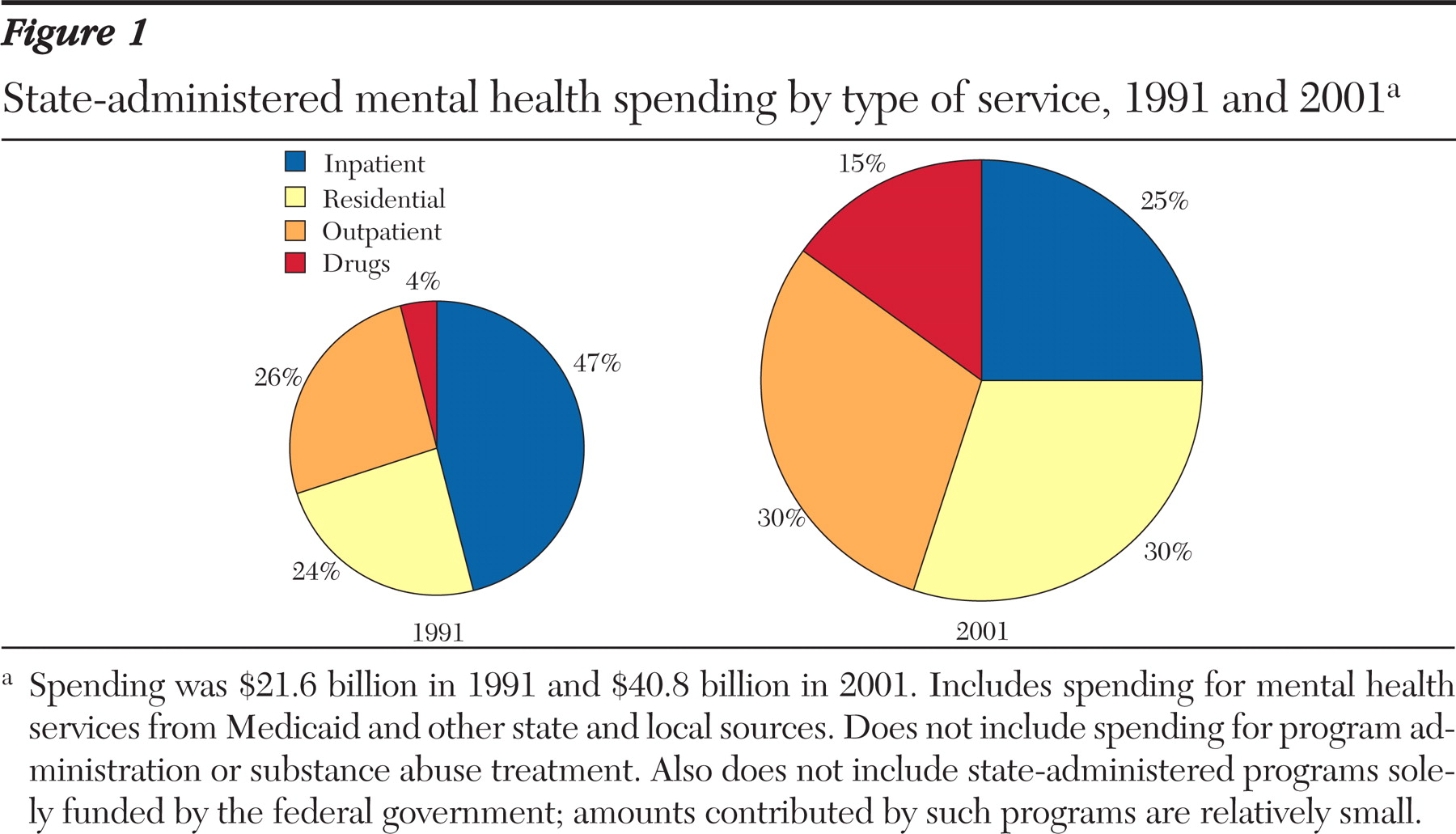

The estimates show spending by type of provider, such as general hospitals, and by type of service—inpatient, outpatient, residential, or prescription drugs. This type of calculation provides a different perspective on spending, because many providers, such as hospitals, deliver multiple types of services.

Figure 1 shows the change in the distribution of state-administered spending for mental health services for 1991 and 2001, by type of service. The changes illustrated here are consistent with those reported by state mental health agencies, in that both show a major decline in the proportion of spending going to inpatient care. However, this decline was due to dramatic increases in other categories while spending for inpatient care remained about the same.

These results suggest that the totality of changes in state-administered spending for mental health services is somewhat more complicated than a change in emphasis from inpatient to community services. Although the percentage of spending going to inpatient care declined, the amount remained quite stable. The amount for outpatient care increased considerably, but the percentage increased only modestly. Larger proportional and absolute increases went for retail psychotropic drugs and residential care. Furthermore, although the combined percentage for inpatient care and residential care decreased, these two types of services still accounted for more than half of state-administered spending for mental health services in 2001.