Depression is a common chronic illness with unique attributes that may hinder implementation of quality improvement in primary care. Compared with physical diseases, mental illnesses are associated with greater stigma and are frequently underrecognized in primary care (

1,

2,

3). Treatment adherence is problematic, with up to a third of patients discontinuing medications after one month (

4). Other challenges to treating depression in primary care include time-constrained patient visits, difficulty coordinating care with mental health specialists, limited reimbursement for evidence-based depression treatments, and limitations in practice structure to accommodate depression care (

5,

6), particularly for practices that serve disadvantaged populations.

Our descriptive and formative evaluation of quality improvement processes by 17 diverse organizations that participated in the Depression Breakthrough Series collaborative, a 13-month initiative applying principles from the Chronic Care Model to improve depression care (

16,

17), was guided by the literatures on diffusion of innovations and social psychological influences on behavior (

18,

19,

20). This literature emphasizes the role of contextual factors (for example, group norms, organizational infrastructure, and availability of resources) and social psychological processes (for example, perceived trade-offs between benefits and barriers) (

21,

22) in enabling or constraining systemic change in health care organizations. Because quality improvement initiatives represent a process of organizational change that occurs over time, we studied initial adoption of innovations as well as whether they persist and become institutionalized in routine practice (

22).

This study addressed the critical gap in the health care literature by considering multiple dimensions of implementation "success." We examined in detail the process of implementing and maintaining change to understand how teams adopt innovative and evidence-based practices for depression care. We specifically focused on three research questions. First, which features of the Depression Breakthrough Series were successfully implemented? Second, what barriers and facilitators did quality improvement teams experience during implementation? Third, how were contextual factors, barriers, and facilitators associated with successful implementation, maintenance, and spread of changes in depression care?

Results

Intercoder agreement

Two evaluation team members independently coded the change activities from senior leader reports (

26) and the other five measures (successes, maintenance, spread, barriers, and facilitators) from the telephone interviews. Initial reliability between coders, based on kappa coefficients, ranged from .52 for facilitators to .80 for spread. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

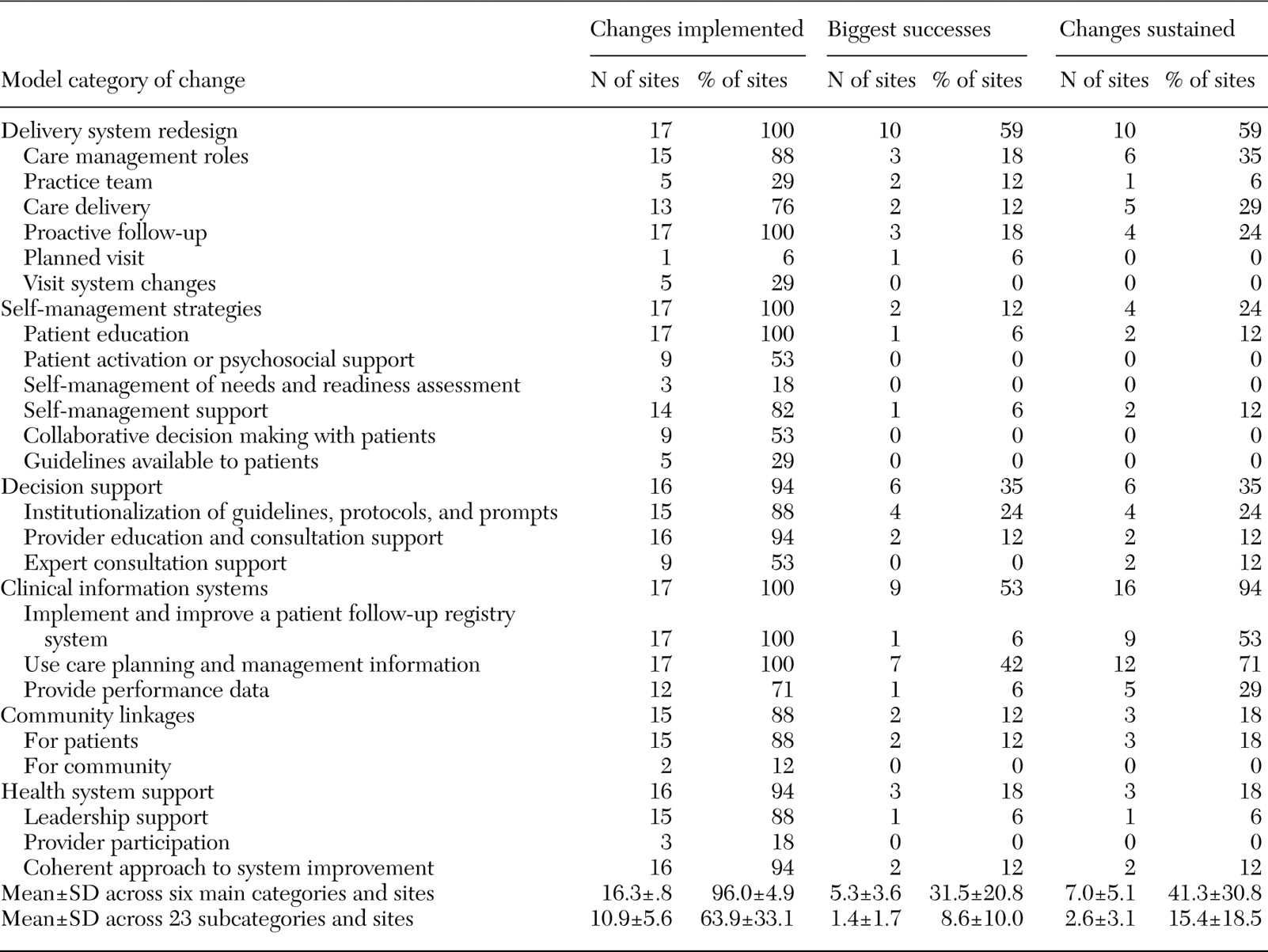

Changes implemented

All 17 sites made changes to their delivery systems, self-management strategies, and information systems (

Table 2); all sites reported some proactive follow-up, patient education, improvements in follow-up through use of a patient registry (required by the collaborative), and use of data from information systems for care management. All but two sites made changes in decision support, community linkages, and health system support.

Self-rated successes

Slightly more than half the sites made changes to delivery system redesign (ten sites, or 59 percent) and information systems (nine sites, or 53 percent) that were "big successes." Although all sites reported changes to improve patient education, and the vast majority tried to improve self-management support (14 sites, or 82 percent), only one site reported a "success" in these areas. Only one site (6 percent) reported no successes, three sites (18 percent) reported success in only one category (delivery system redesign or decision support), four sites (24 percent) reported success in three categories, and nine sites (53 percent) reported success in two categories.

Changes sustained

More sites sustained change in information systems than in any other category (16 sites, or 94 percent). Twelve sites (71 percent) sustained changes to improve the use of care planning and management information, nine (53 percent) to implement or improve patient follow-up by using a depression registry, and five (29 percent) to provide performance data by using information systems. Ten sites (59 percent) reported sustaining delivery system redesign, including care management roles, care delivery, and proactive follow-up.

Spread of collaborative efforts

Fifteen sites (88 percent) reported some form of spread (

Table 3), most commonly to other providers or patient groups within the same location (13 sites, or 76 percent), followed by spread to other disease categories or conditions—including joining other collaboratives (eight sites, or 47 percent)—and then to other clinics in the same organization (seven sites, or 41 percent). Only two sites (12 percent) reported spread to other organizations within the community.

Facilitators and barriers to change

Across all sites, organization or site-specific attributes (for example, clinic structure and location) and leadership support were the most frequently reported facilitators to implementing improvements (11 sites, or 65 percent, for both) (

Table 3). Having appropriate staff and effective team characteristics were other commonly reported facilitators (seven sites, or 41 percent, for both). The most common barriers to success included staff resistance to changes (mostly on the part of primary care providers), difficulty with IT or technical systems (both reported by 13 sites, or 76 percent of sites), time constraints (12 sites, or 71 percent), difficulty finding appropriate staff (11 sites, or 65 percent), and retaining staff (11 sites, or 65 percent, for both).

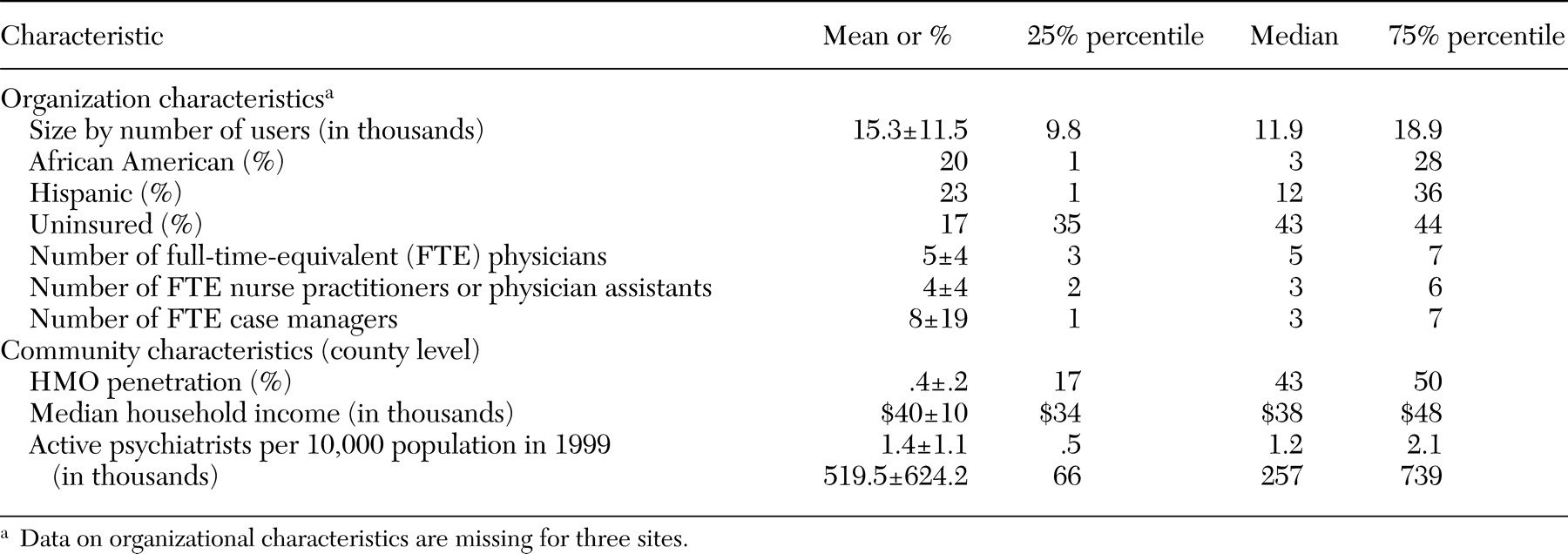

Contextual characteristics and implementation

We observed significant positive correlations (data not shown) for the total number of changes among sites (N=17) in communities with higher median household incomes (r=.51, p=.04) and with more psychiatrists (r=.55, p=.02). For big successes, we observed a significant negative association for sites with more uninsured persons (r=.-60, p=.02). No site characteristics were associated with maintenance or spreading of changes. Sites in communities with more Hispanic clients (r=.50, p=.08) and more uninsured persons (r=.61, p=.03) reported more facilitators (mean±SD=3.6±1.8), and sites with more nonphysicians per 10,000 population reported more barriers (5.7±2.2, r=.56, p=.04).

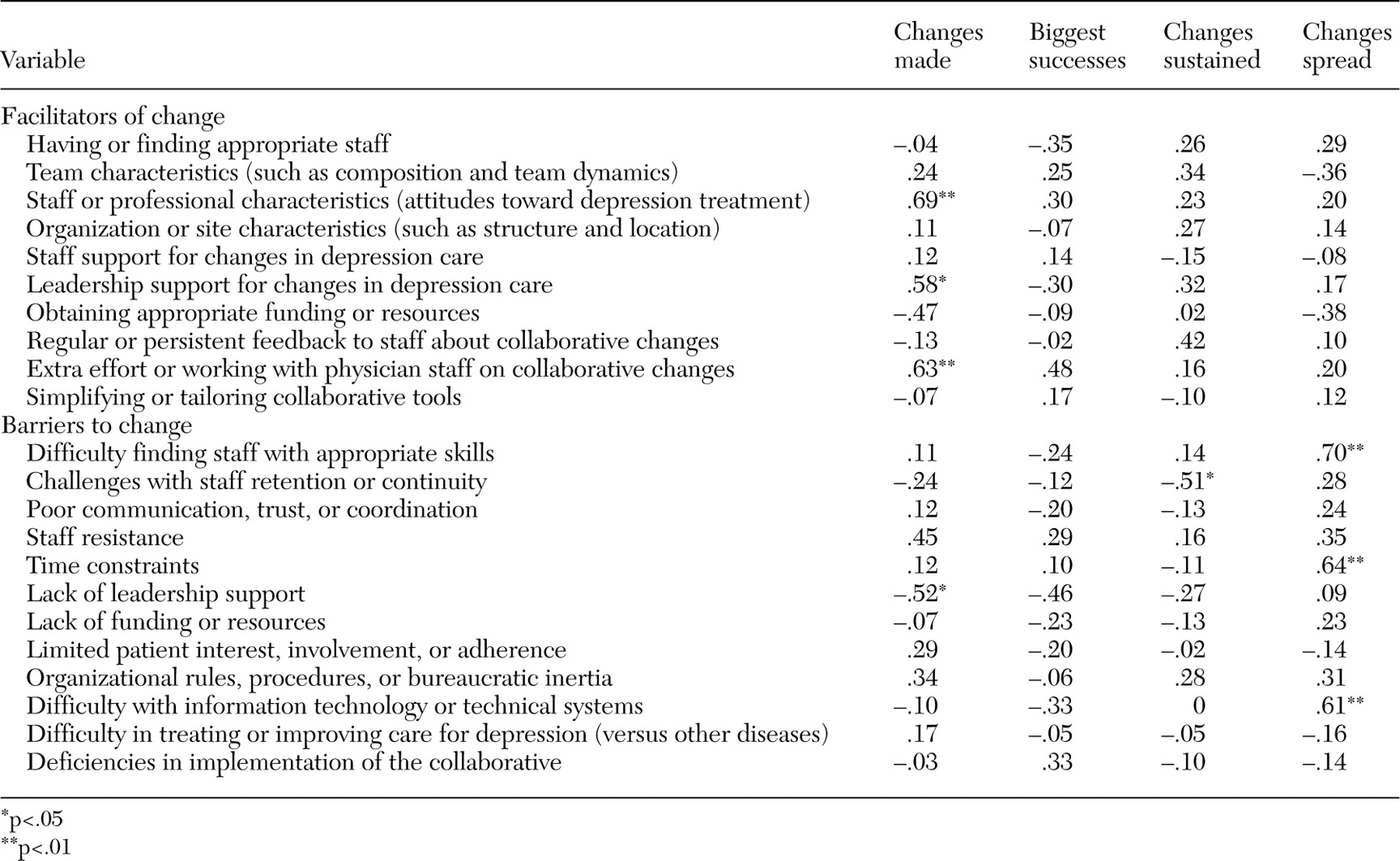

Barriers and facilitators of implementation

Among facilitators, staff characteristics (for example, staff attitudes toward depression treatment, leadership support, and efforts made to work with physicians) were positively associated with change (r=.69, .58, and .63, respectively) (

Table 4), and successfully obtaining resources was negatively associated with change (r=-.47, p=.06). The staff resistance barrier was positively correlated with change (r=.45, p=.07), and lack of leadership support was negatively associated with change (r=-.52, p=03).

Only one facilitator (extra efforts made to work with physician staff) and one barrier (lack of leadership support) trended toward significant associations with the number of perceived big successes (r=.48 and -.46, respectively) (

Table 4).

For maintenance, a positive trend was observed for association between regular feedback to staff about collaborative changes and changes sustained (r=.42, p=09), and staff retention barriers were negatively associated with less change maintenance (r=-.51, p=.03).

No facilitators were significantly associated with spread. However, perceived barriers—including difficulty finding and keeping the right staff (r=.70, p=.002), time constraints (r=.64, p=.006), and IT problems (r=.61, p=.009)—were positively associated with spread.

Network analysis

Network analysis using NetDraw (

29) displays the raw data to illustrate the complexity of important relationships—for example, how different changes sustained (

Table 2) were linked to unique sets of barriers (

Table 3) across sites. This approach allows a third variable, such as a client characteristic, to be added. [A figure illustrating these links is available in the online version of this article at ps.psychiatryonline.org.]

Implementation costs

We estimated the average cost of participating in the collaborative and implementing quality improvement at $118,000 per site, ranging from $30,000 to $252,000 (SD=$72,000). The large variation across sites was attributable mainly to the number of pilot patients (r=.49) and the number of physicians actively involved in the collaborative (r=.81). The mean cost per patient was $879 (only $375 at sites with 300 or more pilot patients). Nursing staff generally accounted for the largest share of costs, and physicians accounted for about 20 percent of labor hours.

Discussion

We found significant and enduring changes to improve care for depression in a variety of primary care practices that participated in the Depression Breakthrough Series Collaborative. Teams made improvements despite the many challenges associated with delivering depression care, particularly in the underserved areas in which participating clinics were located, which suggests that even sites that serve many minority clients benefited from the quality improvement effort (

29).

Moreover, changes were made at a relatively low cost that was commensurate with rates found in other cost-effectiveness studies (

30). Although it is known that quality improvement interventions with multifaceted teams that use evidence-based practices can have positive effects on care for depression and its outcomes (

8,

9), we know little about how the complex process unfolds at the team and practice levels. To address this gap we have described the types of changes that teams made and explored characteristics that are linked with successful implementation, maintenance, and spread of improvements for depression.

Our data suggest some lessons for using collaborative approaches to improve depression in primary care settings. First, although some changes were adopted by all the teams (proactive follow-up, patient education, patient registry systems, and care planning), other types of changes were not (provider participation and patient activation). This pattern suggests that future collaboratives teach how to obtain this fruit at the top of the tree.

Implementation of change was consistent with the guidance provided by the collaborative faculty, who emphasized the role of care managers (for example, redesign of the delivery system) and patient registries (for example, information systems). These areas are critical, but the uneven emphasis on certain categories of change is inconsistent with the model's objective of achieving success across all six categories.

Quality improvement efforts are more likely to be maintained over time if they involve input from all relevant parties, especially top management. Furthermore, teams that may not have had buy-in at all three levels (patients, clinicians, or other organizations) faced additional challenges to comprehensive change. Rubenstein and colleagues (

7) found that teams reported support from organizational leadership to be an important facilitator for successful quality improvement in depression care. Similarly, in this study, the only barrier that significantly affected perceived success was poor leadership support. For example, although one organization faced severe financial limitations, the chief executive officer's strong advocacy for the depression program and support through "in-kind" resources was critical in the survival and effectiveness of the collaborative team. In another organization, changes were implemented mainly after the end of the collaborative, when a more sympathetic leader was hired. Consistent with the finding of Goldman and colleagues (

31), these results suggest that implementation of evidence-based services requires having appropriate incentives in place and the ability to overcome systemic barriers.

We also found that smaller clinics were more likely to sustain change over time. In a smaller practice, a quality improvement project may be more visible and easier to manage by a few dedicated individuals. By contrast, such efforts may be susceptible to dilution in larger systems of care, or there may be other competing quality improvement efforts. Another explanation is the relative ease of reaching critical mass through training investments in smaller organizations to sustain team efforts.

Sites that were particularly successful at implementing and sustaining changes were less likely to spread those changes. This finding may be related to the need to institutionalize changes in the initial setting before extending them. Also, as noted above, many sites that were successful at sustaining changes were smaller, which may reflect less need, pressure, or even opportunity to spread, if all or most of the site was included in the initial implementation.

The finding that sites that spread innovations to other patient groups or locations reported more barriers could become manifest as barriers emerge or become apparent (when the scope of changes begins to affect wider portions of the care system). In contrast, change efforts that remain limited in scope or depth would encounter few points of resistance. Thus an increased elicitation of barriers may in fact be a corollary to success, at least in terms of spread. Alternatively, in certain sites with fewer initial changes, expansion of change activities after the collaborative period may signify delayed implementation rather than actual spread. This possibility could also partially explain the negative correlation between having obtained adequate resources and the amount of change reported during the collaborative.

Some specific challenges identified by participants included language barriers that made hiring and retaining qualified staff daunting in sites with larger Hispanic populations. Moreover, the qualitative descriptions of implementation process from the interviews emphasized the interrelatedness of barriers—for example, trouble developing workable computerized systems was frequently blamed on lack of appropriately skilled staff as well as on difficulty arranging dedicated staff for updating and managing depression registries (often manual or incompletely automated). In turn, difficulty with registries was noted to limit spread. Likewise, the strategy of devoting extra effort to get physician staff to accept and implement changes (by nearly a third of the sample) occurred only at sites that also reported staff resistance and was accompanied by more change activity. This pattern suggests that such a concerted and persistent approach with physicians proved effective in the face of substantial staff resistance.

Although this study has extended research on quality improvement by assessing success of implementation in detail over many dimensions and across more sites than is typical in such research, the analyses had several limitations. First, although a sample of 17 sites is large for such studies, its statistical power is limited to detecting significant site-level differences. Consequently, several hypothesized and plausible correlations, although high, were not significant. Furthermore, the sample of organizations was heavily weighted toward public-sector community clinics that serve predominantly disadvantaged populations and, although geographically diverse, might preclude generalization of findings to all primary care practices. This study was also restricted to self-reported data, which could be subject to inaccurate retrospective recall and even optimistic bias, particularly regarding spread, because team leaders may lack full knowledge of the actual degree of implementation beyond their site. Finally, the inability to collect enough patient-level outcome data for participants in this particular collaborative prevented us from relating implementation success to the health and functioning of individuals who were receiving care.

Nonetheless, our findings suggest that a number of changes, such as the use of care planning and management information, may be relatively easy to implement and sustain, whereas other changes, such as provider participation and patient activation, although equally important, are more difficult. Unlike for diabetes care, few organizations reported success in the area of self-management of depression. In general, the review of barriers and facilitators suggests that quality improvement for depression may require extra attention or resources, or different strategies with clinicians to successfully implement participatory practice changes and activate patients (

32), because staff attitudes are an important factor in implementing change efforts (

33).