In Canada and other parts of the world, psychiatric services for persons with mental retardation, as defined in

DSM-IV-TR, were once provided through institutions. In the 1970s, plans to downsize and close these institutions were initiated, and, since then, persons with mental retardation have been directed to the generic mental health system for their psychiatric needs (

1). Little information is available about how patients with both mental retardation and a psychiatric disorder differ from those who do not have intellectual impairments in terms of their demographic characteristics, symptom profile, and clinical needs. Such information is critical to delivering effective mental health services to these patients (

2).

A small number of studies have compared persons with and without co-occurring mental retardation who are receiving psychiatric services (

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8). These studies have shown that the patients with mental retardation are typically younger, are more likely to live in dependent living settings (with family or in group homes), and are less likely to be married or have children. With regard to symptom profile, they tend to have higher rates of comorbid medical conditions, more problems with aggression, and lower rates of substance abuse compared with other patients. In terms of aggression, patients with mental retardation have been reported to display more assaultive behavior and to receive more chemical and physical seclusion and restraint than other patients (

4,

6,

9,

10).

Lohrer and associates (

6) and Saeed and colleagues (

4) reported a longer stay for inpatients who had both mental retardation and a psychiatric diagnosis than for patients who did not have mental retardation. Several researchers have commented on the intensive clinical needs of this patient group and the high level of care required if they are to be supported outside the hospital (

4,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15). However, no studies have directly compared the level of services required by patients who have mental retardation and a comorbid psychiatric illness with the levels required by other groups of patients.

The study reported here compared the clinical profile and service needs of patients with both mental retardation and a psychiatric diagnosis with those of other patients receiving tertiary-level mental health care in Ontario. The goals of the study were to determine the prevalence of co-occurring mental retardation within the tertiary care psychiatric hospital system, to examine the patient characteristics and symptom profile of the group with both mental retardation and a psychiatric diagnosis compared with those of other patients receiving tertiary mental health care, and to calculate and compare the recommended level of care for those with and without mental retardation.

Discussion

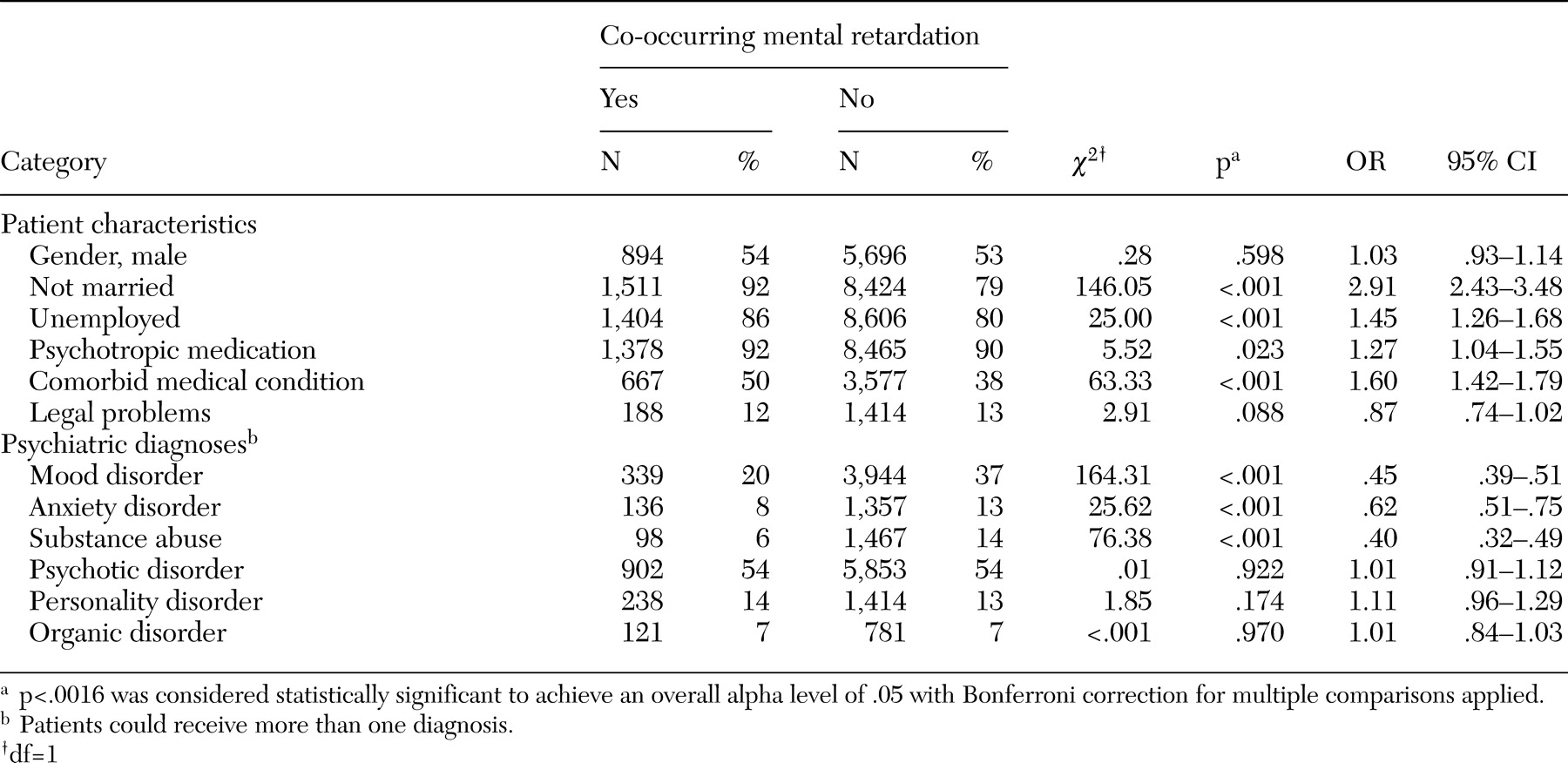

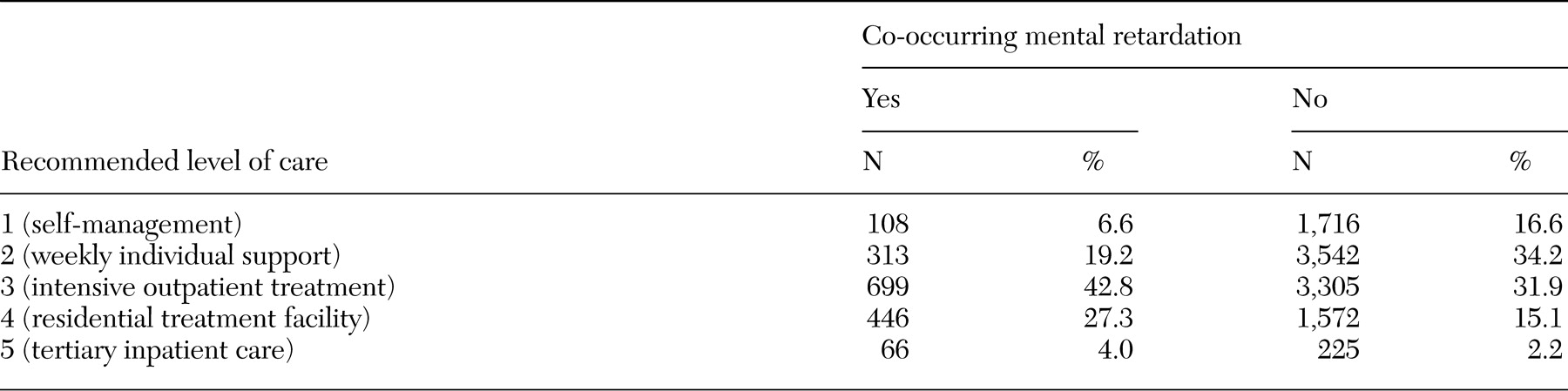

This study was conducted to determine the patient characteristics and clinical needs of persons with both mental retardation and a psychiatric diagnosis who were currently being served by the tertiary care psychiatric hospital system in Ontario. The results of the study provide important information for those planning services for this population. As many as one in eight individuals (13.4 percent) served by the tertiary mental health care system in Ontario have co-occurring mental retardation. Patients with both diagnoses differed from patients who did not have mental retardation with regard to demographic characteristics and tended to have a more severe diagnostic and symptom profile, a greater lack of resources, and a higher recommended level of care. Despite their more severe profiles, only a small percentage of patients with co-occurring mental retardation were rated as requiring long-term inpatient care (level 5). A majority were rated as requiring either intensive outpatient support (level 3) or residential treatment (level 4).

In terms of patient profiles, patients who had both mental retardation and a psychiatric diagnosis were more likely to be single, to be unemployed, to have comorbid medical conditions, and to have a longer stay than patients who did not have mental retardation. This presentation matches the profile reported by Saeed and associates (

4), Hurley and colleagues (

5), and Lohrer and colleagues (

6) in their studies of patients in acute care settings. The patients with both diagnoses had lower rates of substance abuse, which has been reported elsewhere (

6,

8) and may be partly explained by the fact that persons with mental retardation have limited access to substances because of their supervised lifestyle (

25).

The patients with co-occurring mental retardation who were included in the study reported here were found to have lower rates of mood and anxiety disorders than other patients. This finding is inconsistent with the general finding that persons with mental retardation have an increased risk of affective disorders (

26). One explanation for our finding is that clinicians who do not have specialized training can underdiagnose or misdiagnose mood and anxiety disorders among persons with mental retardation (

5,

27). The lower rates may also reflect the fact that individuals with mental retardation and mood or anxiety disorders do not tend to receive the attention of tertiary-level services. Rather, it is those who have challenging behaviors, such as aggression, who receive such services (

28,

29).

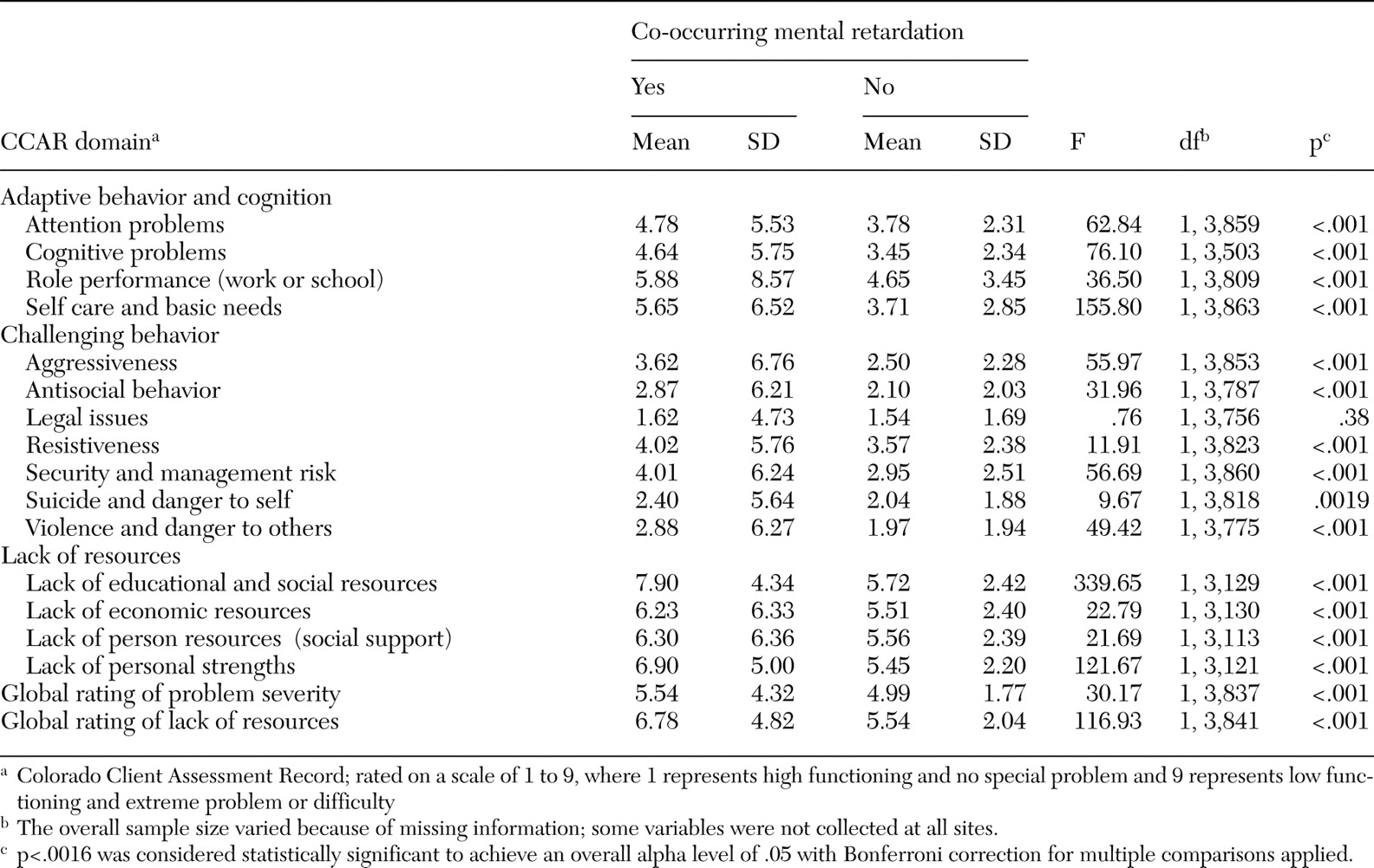

In terms of patient profiles, the results of this study suggest that persons who have both mental retardation and a psychiatric diagnosis are disadvantaged as a result of adaptive behavior and cognitive limitations, challenging or aggressive behavior, and lack of resources. Adaptive limitations (poor attention and cognitive dysfunction) make it more difficult for patients who have co-occurring mental retardation to participate in treatments that have been developed for the "typical" patient (

30,

31). Compounding these functional limitations are problems with aggression to self and to others, referred to in the literature as "challenging behavior." Often, it is this challenging behavior rather than psychiatric symptoms that receives clinical attention (

29,

32) and jeopardizes community placements (

13). Finally, persons with co-occurring mental retardation lack internal and external resources, which makes it difficult for them to obtain appropriate services, to maintain gains made in therapy, and to avoid regressing without extensive professional supports.

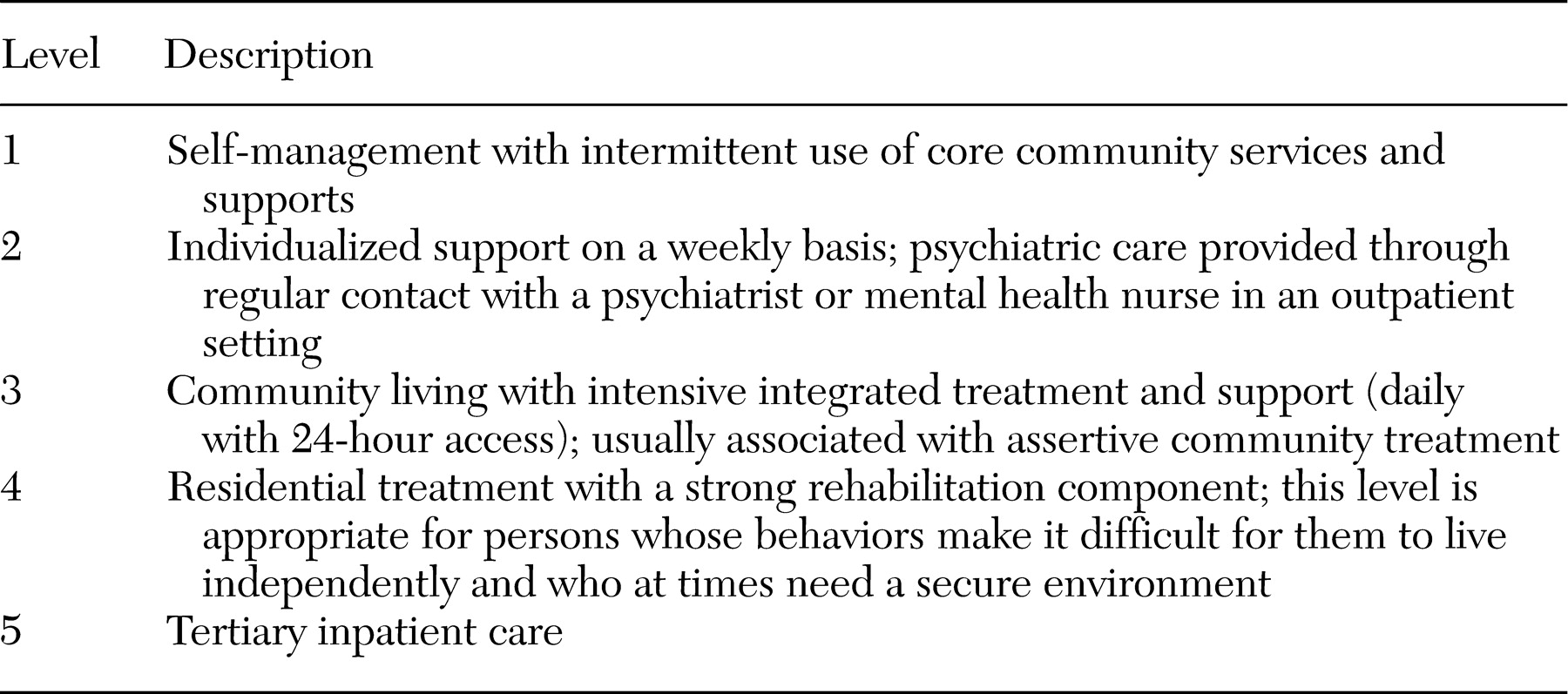

An important finding of this study from a service delivery perspective is that the recommended level of care for patients with co-occurring mental retardation is higher than for other patients. However, only a few patients in this study who had co-occurring mental retardation were deemed to require the highest level of support—inpatient tertiary care (level 5). This finding implies that a large percentage of individuals who were receiving level 5 care at the time of the study were deemed to require a lower recommended level of care. In other words, level 3 and 4 supports would be more appropriate for many of these individuals. Level 4 supports (highly staffed community residences with a strong therapeutic component) and level 3 supports (intensive case management services, such as specialized assertive community treatment teams) have evidenced some benefit for persons with lower functioning (

33,

34,

35). Perhaps the longer stay among patients with co-occurring mental retardation in this study is in part a reflection of the shortage of level 3 and level 4 supports and the reluctance of agencies that provide intensive outpatient services to accept these more challenging, higher-need individuals. This question has been discussed by others in Ontario (

4), the United States (

13), and the United Kingdom (

15).

An important caveat should be kept in mind in the interpretation of this study's findings. In this study, the patients with co-occurring mental retardation were defined as those who had a clinical diagnosis of mental retardation and a psychiatric disorder. Accurate psychiatric assessment of low-functioning individuals requires assessment from a psychiatrist or a psychologist who is specifically trained in making this type of dual diagnosis. Unfortunately, such specialist diagnostic skills have historically been limited in tertiary mental health services. Thus it is likely that a portion of our sample may have appeared clinically to have mental retardation but without correctly meeting

DSM-IV criteria for mental retardation (IQ below 70, adaptive behavior deficits, and onset before age 18) (

11). Similarly, it is likely that a number of patients in the group of patients with both diagnoses had been given a misdiagnosis—for example, psychotic-like behaviors may have led to diagnosis of psychosis when in fact the behaviors were related to another underlying cause (

27,

36).

This study had several limitations, which should be taken into consideration in interpreting its findings. First, data reported here are based on secondary analyses of data developed for another purpose. Issues such as accuracy of diagnoses of mental retardation or developmental disability and psychiatric diagnoses cannot be addressed by using this database, only through further research. Also, numbers reported here are estimates based on inpatients who were sampled on a given census day; not every outpatient was surveyed. Second, findings are based on the subgroup of persons with co-occurring mental retardation who were being served by Ontario's tertiary-level psychiatric hospitals. The study did not address the needs of patients obtaining services outside the tertiary care system or not receiving any services. Third, the findings may be unique to Ontario and not generalizable to other jurisdictions. Only comparable research in other places will address this issue. Finally, the level-of-care algorithm has demonstrated good concurrent validity, yet it is still relatively new and would benefit from further testing, especially in psychiatric populations with complex conditions.