A number of recent studies have documented the prevalence of co-occurring mental disorders among adolescents who are referred to substance abuse treatment (

1,

2). Estimates of the rate of co-occurring disorders for this population have ranged from 60 percent to 80 percent. In these studies, youths with comorbid conditions had greater severity of substance use and often had related problems with family, school, and criminal involvement (

1,

2). These youths were more likely to experience trauma and had less supportive family environments. After receiving substance abuse treatment, these youths were more likely to experience relapse, resume substance use, or engage in illegal behavior. Most researchers studying this population have concluded that better integration of substance abuse treatment and mental health services would improve the quality of care (

3,

4).

Compounding this situation is the lack of health coverage to pay for needed behavioral health services and inadequate public funding to cover treatment for youths who do not have health insurance. About 35 percent of children under the age of 22 years lack private insurance; of these, only a little more than half qualify for Medicaid, leaving an estimated 14 million uninsured (

5).

Medicaid spends approximately $20 billion per year on mental health services and approximately $1 billion for substance abuse treatment. Besides Medicaid, major public funding for substance abuse and mental health treatment programs are two block grants administered by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. In fiscal year 2002 the Substance Abuse Prevention and Treatment block grant funds accounted for 40 percent of state expenditures for substance abuse prevention and treatment, whereas the Center for Mental Health Services block grant funds accounted for only 3 percent of state expenditures for community-based mental health care (

6).

During the 1990s, the state of Oregon took several steps to improve access to medical and behavioral health services. The Oregon Health Plan significantly expanded eligibility and adopted a managed care approach to pay for the expansion. At the same time, the state was shifting non-Medicaid resources away from state hospitals to strengthen the continuum of community-based services. However, these changes were targeted primarily at adults rather than children.

The naturalistic study reported here used administrative data from Oregon to determine whether Medicaid-eligible adolescents who presented for publicly funded substance abuse treatment with co-occurring disorders were more likely to receive mental health services than their uninsured counterparts after group differences and systemic changes over time were controlled for.

Methods

We selected admission records from Oregon's treatment database—the Client Process Monitoring System (CPMS)—for 25,813 adolescents, aged 12 to 17 years, who had been admitted to publicly funded treatment for a substance use disorder from 1994 through 2002. Only youths who lacked private health insurance were included in the sample. Access to administrative data for this study was given institutional review board approval and was covered by data sharing agreements with state agencies.

We categorized the youths as either Medicaid-eligible or non-Medicaid-eligible on the basis of their Medicaid eligibility during the month they were admitted to substance abuse treatment. As expected, the groups differed significantly on four of the demographic characteristics examined. Medicaid-eligible youths were more likely to be female, nonwhite, younger, and referred by social services agencies compared with non- Medicaid-eligible youths. The differences, although small to moderate, were highly significant (p<.001) because the sample was large.

To control for the differences between the Medicaid- and non-Medicaid-eligible groups, we applied propensity score analysis (

7,

8). Logistic regression predicted Medicaid eligibility from characteristics available in the CPMS admission record. The resulting propensity score assessed the probability of being Medicaid eligible given all observed covariates. This score was used as a covariate in the subsequent analysis to predict use of mental health services.

Because the CPMS admission record lacked a direct measure of mental health functioning, we developed and validated a mental health need index by using a prospective sample of 125 Medicaid-eligible adolescents who had been interviewed as part of a previous study (

9) when they entered substance abuse treatment between June 1998 and January 2000. In the validation analysis, CPMS variables were used to predict Youth Self Report (YSR) (

10) scores. The YSR syndrome scales map well to clinical diagnoses, and scores are predictive of proximal indicators of need for mental health treatment, including past use of services. The resulting regression equation was applied to the full adolescent sample as a proxy for need.

Logistic regression was used to predict use of mental health services during the same calendar year in which an adolescent was first admitted to substance abuse treatment. The propensity score and need index were entered to control for differences in selection into Medicaid and differences in need for mental health services. Medicaid eligibility, year of admission, and Medicaid-by-year interaction variables were entered in the second block.

To examine subgroup differences more closely, we conducted separate logistic regressions for the Medicaid- and non-Medicaid-eligible groups, using the full set of predictors. [An expanded methods section is available in the online version of this brief report at ps.psychiatryonline.org.]

Results

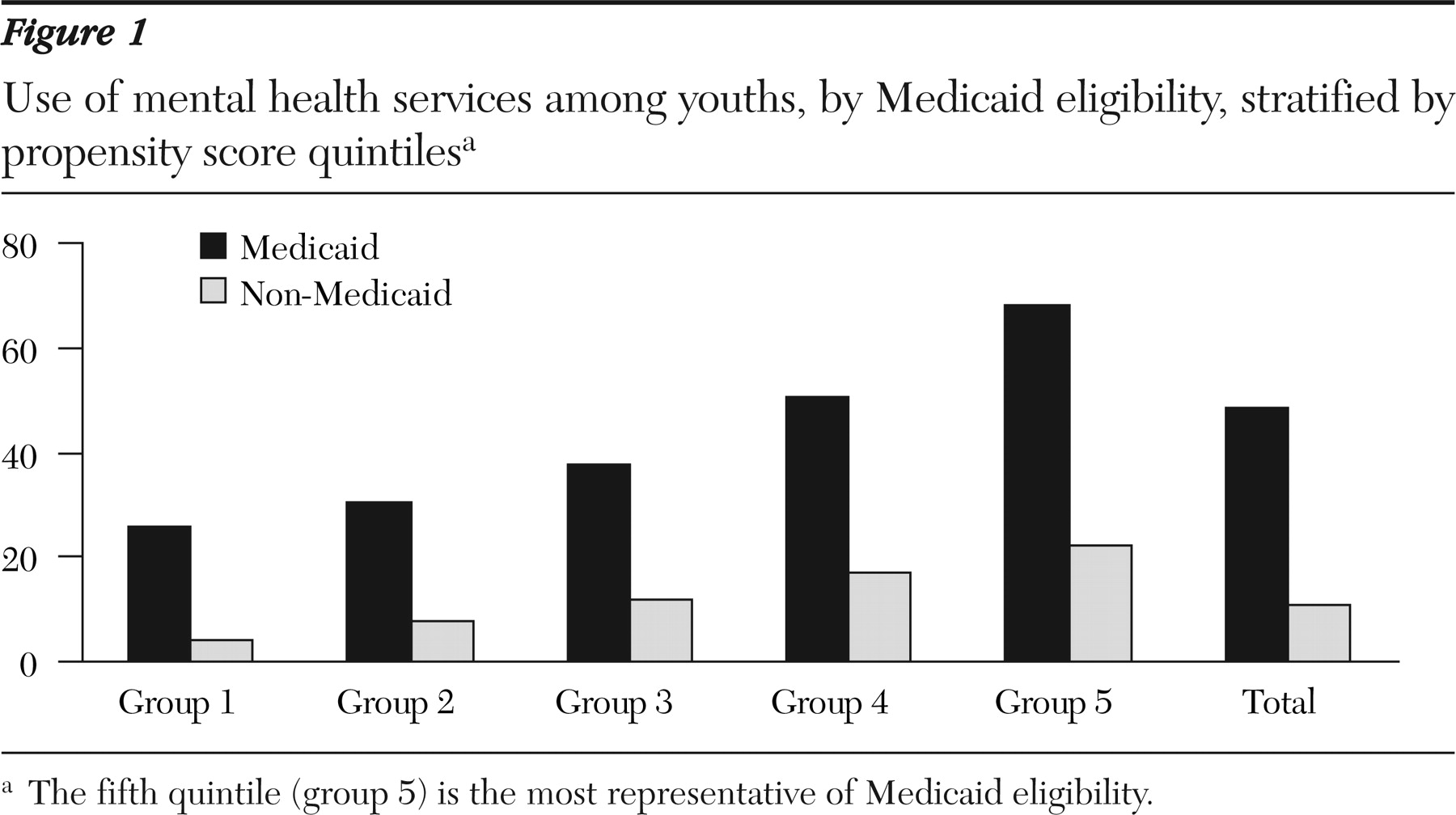

About 42 percent of the Medicaid-eligible youths received at least one mental health service in the same year that they were admitted to substance abuse treatment, whereas only about 8 percent of the non-Medicaid-eligible youths used a mental health service. The dramatically higher utilization rate for Medicaid-eligible youths held up across the entire observation period. In this purely descriptive analysis, we made no adjustment for differences in the characteristics of youths in the two groups. Medicaid-eligible youths had a slightly higher average mental health need index.

Figure 1 shows the relationship between Medicaid coverage and use of mental health services, with group differences and mental health need controlled for. Utilization rates were stratified by propensity score quintile. Youths with high propensity scores—that is, those who were more representative of the Medicaid population—had much higher utilization rates than youths with low propensity scores, regardless of Medicaid eligibility. However, as expected, Medicaid-eligible youths were consistently more likely to gain access to mental health services at all levels of the propensity score compared with non-Medicaid-eligible youths.

To test the relationship illustrated in

Figure 1, a logistic regression was conducted to predict use of mental health services, with the propensity score and mental health need as covariates (χ

2=5,452, df=5, p<.001; Nagelkerke R

2=.29, 81 percent correctly classified). The main effects of interest were Medicaid eligibility and year. Medicaid-eligible youths were nearly five times as likely (odds ratio [OR]=4.8) to use mental health services. Year was also significant, with a 4.4 percent increase in use per year (1994 through 2002). The year-by-Medicaid interaction was not significant.

A sensitivity analysis was conducted to determine whether the estimated effect of Medicaid eligibility was sensitive to potential unmeasured predictors associated with both Medicaid and use of mental health services. Omission of the four strongest predictors only changed the Medicaid odds ratio 3 to 16 percent. Thus the estimate was relatively insensitive to omissions; an unobserved variable would have to be a much stronger predictor than any of the omitted variables to account for the finding.

The subgroup analysis for the Medicaid-eligible group showed that Hispanic and Native-American youths were less likely to use mental health services than white youths (χ2=1,535, df=21, p<.001; R2=.23, 68 percent classified correctly). For the non- Medicaid-eligible group, there was also evidence of lower use among Native Americans than whites but more use among African Americans (χ2=879, df=19, p<.001; R2=.10, 89 percent classified correctly). In both groups, younger adolescents, youths who lived in institutions, youths who had been referred from social service and mental health agencies, and youths who had more years of substance use were more likely to use mental health services. Within the Medicaid group, youths who had disabilities or who were in foster care were more than three times as likely to use mental health services, and females were twice as likely to use mental health services. Within the non-Medicaid-eligible group, youths with an arrest history or with various indicators of more severe substance use were more likely to use mental health services than other youths. [An expanded results section is available in the online version of this brief report at ps.psychiatryonline.org.]

Discussion

The results of this study suggest that Medicaid eligibility was strongly associated with use of mental health services by adolescents who presented for publicly funded substance abuse treatment. Even after we controlled for admission characteristics that predispose youths to need or to seek services, Medicaid-eligible youths were nearly five times as likely as non-Medicaid-eligible youths to use mental health services within a given year. This finding is not surprising given that Medicaid is the primary source of public funding for mental health treatment and persons who lack insurance typically lack the means to pay for these services out of pocket. However, the importance of Medicaid in promoting access to care has generally been overlooked in the literature and has not always been prominent in policy discussions about access. Moreover, even youths who were Medicaid eligible had utilization rates that were far below the estimated prevalence of co-occurring mental health disorders, which suggests a treatment gap for this group as well.

The modest increase in use over the study period for both groups may be due to a combination of factors. Under the Oregon Health Plan there was a large influx of new adult mental health clients. At the same time, the state was deinstitutionalizing services covered by block grant funds. Increasing attention was being given to the issue of co-occurring disorders. However, these changes were gradual and targeted primarily adults.

The subgroup analysis indicated differences in use of mental health services within both groups. Although it is likely that some of the differences reflect greater mental health need that was not captured by the need proxy, the results provide some evidence of disparities for two minority groups and suggest certain pathways to treatment that may facilitate access. These issues deserve more attention.

Observational studies have inherent internal validity problems due to the lack of control for assignment to treatment. Propensity score analysis helps control for group differences but can adjust only for observed covariates and may not have adequately adjusted for selection into Medicaid. Also, a direct measure of mental functioning was lacking.

The sample for this study was drawn from a single state. However, states differ significantly in the structure of community treatment systems, the design of the Medicaid benefit for behavioral health care, and the relationship of Medicaid to other funding streams. Further studies are needed to determine the degree to which these findings generalize to other settings.

Conclusions

Greater access to mental health services for Medicaid youths should be considered in both state policies and research design. States that are considering ways to better serve adolescents with co-occurring disorders would do well to examine ways to promote Medicaid enrollment or expand eligibility. Studies of access and utilization in the public sector should include Medicaid coverage as a key covariate.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by grant R01-DA0-15060 from the National Institute of Drug Abuse and grant 51530 from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.