In their Open Forum in this issue, Watson and colleagues (

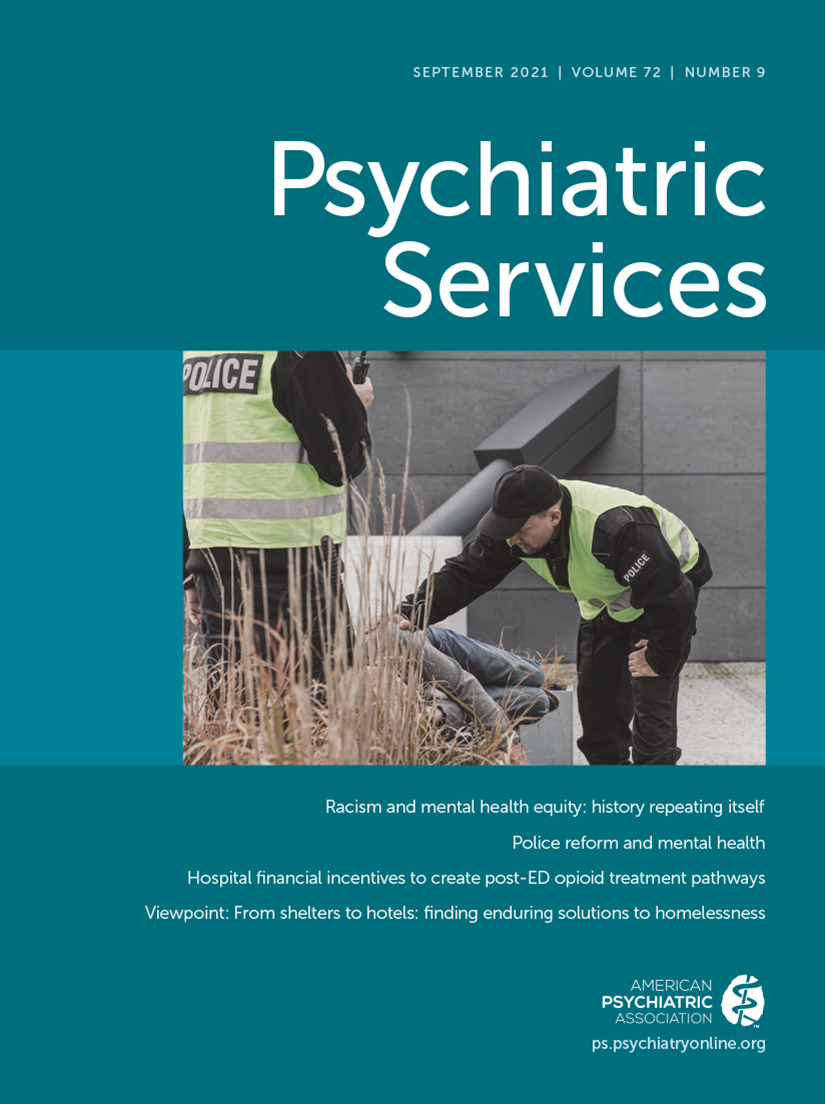

1) outline the circumstances that led to reliance on police as the primary responders to mental health crises, describe crisis intervention team and coresponder models that currently predominate in discussions of improving police response to such crises, and ultimately argue for the importance of shifting response to such crises away from law enforcement. We agree wholeheartedly with the authors’ assessment of the role that mental health professionals can and should play in this aspect of police reform. Also critical is a complementary focus on the well-being of police themselves to assess their capacity to respond appropriately to mental health crises.

When President Obama’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing released its final report in May 2015, the construct of officer wellness and safety was highlighted as an essential pillar of comprehensive U.S. police reform. The report argued that the well-being of police officers “is critical not only to themselves, their colleagues, and their agencies but also to public safety.” In addition to officers’ risk of physical injury and death, the report refers to the mental and emotional injuries that police regularly experience in their profession. Moreover, the report elaborates that beyond the obvious detrimental effects such strains have on officers, if the mental health challenges precipitated by the unique nature of police work are unaddressed, they are likely to have detrimental consequences for the public.

Research on the prevalence of mental health concerns among the law enforcement population is extensive. Officers’ chronic exposure to direct and secondary trauma is known to increase the risk for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, anxiety, substance use, and a host of physiological changes, such as rising cortisol levels and increases in cardiovascular reactivity. Moreover, the ill effects of such stressors on mental health have been documented in the general population. Individuals struggling with repeated exposure to traumatic stress can experience significant cognitive and behavioral changes that affect quality of life and social behaviors. It is surprising, then, that little research has integrated these two bodies of literature to strategically examine the potential, and likely, negative effects of poor mental health among police officers on the quality of their engagement with the public. Moreover, the results of the extant literature in this area have been mixed, pointing to a pressing need for more comprehensive and nuanced studies and theory development.

Policing involves a range of goals, such as crime control, problem solving, relationship building, and, of course, crisis response and diversion. Each of these creates multiple contexts in which officers can exercise discretion. Researchers do not yet know if and how officer mental health may affect decision making in each of these realms. To provide a concrete example, the well-documented elevated prevalence of PTSD among police likely results in a combination of danger-focused cognitions and physiological hyperarousal that could have negative downstream effects on officers’ tactical decision making, ability to engage de-escalation techniques, and reactions to members of the public. It is conceivable that the erratic behavior of an individual in crisis could be perceived as more threatening by an officer experiencing PTSD compared with an officer who is not so affected.

Some may argue that a focus on police officers’ concerns is misplaced. However, even intuitively one understands that the person charged with addressing the range of needs of the public should be healthy—physically and emotionally. We propose that mental health professionals have a key role to play in this aspect of police reform. In addition to pursuing rigorous research on the relationships between officer mental health and the quality of public interactions, there is also the need for developing targeted, evidence-based interventions specific to preserving law enforcement officers’ well-being. Moreover, as police officers are known to underutilize mental health services, barriers to service utilization should be documented, and strategies to dismantle service barriers for law enforcement must be developed and implemented.

Research on police officer mental health and the strategic development and implementation of targeted mental health interventions for U.S. law enforcement have long lagged behind—to the detriment not only of officers but also of the public whom they serve.