Introduction

This paper aims to provide a practical description of delivering method of levels (MOL) therapy for psychosis using case examples to illustrate problem conceptualisation and the process of therapy. Some key theoretical principles for understanding psychosis are outlined along with an overview of what MOL therapy is and what it might look like in everyday clinical practice. The main principles will be outlined, followed by detailed examples of the therapy in application. The language and terminology used throughout this paper may overlap with terms used in other theoretical and therapeutic orientations, but the meanings are likely to reflect somewhat alternative concepts and principles. Some direct references to psychodynamic approaches (PA) and cognitive behaviour therapy for psychosis (CBTp) will be made to help illustrate some potential resemblances and distinctions with MOL. A comparison of some main therapeutic features and concepts across the three approaches is summarised in

Table 1.

Method of Levels is a therapeutic approach based on a direct application of perceptual control theory (PCT), which provides a functional explanation of human behaviour (

Powers, 1960,

1973,

1990,

1998,

2005,

2008). A strength of PCT is that it is a robust scientific theory specifying precise mechanisms of mental functioning, which makes it amenable to direct testing. There is multidisciplinary evidence supporting the theory based on simulations and modelling of human behaviour (e.g.

Marken, 2001;

Powers, 1989,

1999). For the purpose of the current paper, only the key aspects of the theory relevant to understanding psychosis will be referred to (for detailed descriptions, reviews of the theory and evidence see

Marken & Mansell, 2013;

Carey, Mansell, & Tai, 2014; the evidence base is described in

Carey, Carey, Mullan, Spratt, & Spratt, 2009;

Carey & Mullan, 2007,

2008;

Carey, Tai, & Stiles, 2013;

Tai, 2009). Method of levels has been applied transdiagnostically to treat a broad range of psychological problems across different diagnoses. This is advantageous when working with individuals having psychotic experiences because psychosis, though commonly associated with schizophrenia, occurs across a much wider range of diagnoses. Also, people diagnosed with disorders, such as schizophrenia, frequently meet the diagnostic criteria for a number of other disorders as well, such as personality disorders, anxiety disorders, and mood disorders (Buckley, Miller, Lehrer, & Castle, 2009), requiring therapists to be able to work with multiple problems simultaneously.

Perceptual control theory identifies three main principles of human functioning that form the cornerstones of MOL therapy. These principles are control, conflict, and reorganization, and these will be described briefly below in relation to psychosis. The principles direct how psychological distress is conceptualized in MOL, which is always based very much on problems specific to the patient. The principles also guide the process of therapy where the emphasis is on why the therapist is doing what she is doing as opposed to what is being done. Psychodynamic approaches and CBT specify particular techniques and procedures to be routinely implemented during therapy, for example, interpretation in PA, and behavioural experiments in CBT. However, in MOL the emphasis is on the outcome. The means by which this is achieved varies greatly depending on the needs of the patient. As such, it is not possible to describe the application of MOL to psychosis merely as a set of techniques because what the therapist does might appear different depending on the patient with whom she is working. This is illustrated further throughout this paper. If one were to observe what an MOL therapist is doing when working with different patients, a range of therapist behaviours, rather than a distinct set of techniques, would be observed. At times some of what the MOL therapist does bears resemblance to other therapeutic interventions; such as Gestalt therapy, psychodynamic therapies, and CBT and mindfulness approaches, however, any such similarities are not intentional. In this respect, MOL cannot be described as a new therapy, rather, it is the application of PCT principles, which guide the MOL therapist, that are distinct and diverge from other psychological approaches to psychosis. The three PCT principles, outlined below, are always applied consistently when working with any problem, not only psychosis, so that why the therapist behaves as they do should remain transparent and specific.

Control

The fundamental tenet of PCT is that the survival of all living organisms is dependent on being able to control (

Powers, 2008). People control preferred states—for example, how warm we want to feel, how spicy we like our food to taste, or how we would like others to see us. The term “preferred state” could also be used synonymously with terms such as goal, standard, reference, value, or perception; the important point is that all living beings strive to maintain these preferred states. This concept of homeostasis might be more familiar when thinking about biological processes, such as body temperature control (

Carey, Mansell, & Tai, 2014). For example, the preferred state for body temperature is 98.6°F (37°C), and if the outside environment, such as severe cold weather, were to affect the person, that individual would take action to reduce the impact of the environment to maintain temperature control; such as shivering, putting warmer clothes on, going indoors, etc.

People place great importance on having control over behaviours, emotions, thoughts, relationships, or some other area of their life (

Carey, 2008). Loss of control (for example, control over thoughts, the number of hours you want to spend at work, the degree of closeness you perceive yourself to have with family members) can lead to mental health problems (

Powers, 1973; 2005;

Tsey, Whiteside, Deemal, & Gibson, 2003;

Tsey, 2008). The importance of control for mental health is not a new idea (e.g. Fiske & Taylor, 1991; Thompson & Spacapan, 1991). For example, central to psychodynamic theory is the concept of preferred self-regulated states, for which psychological defenses are a mechanism by which these are maintained (

Freud, 2010). Control specifically within psychosis is also well documented. Thought control strategies are also an important component within CBT for psychosis (e.g. Morrison & Wells, 2000). Loss of interpersonal control is a developmental factor in fomenting psychosis (

Ballon, Kaur, Marks, & Cadenhead, 2007;

Berry, Barrowclough, & Wearden, 2008;

Pinkham, Penn, Perkins, Graham, & Siegel, 2007), and lack of control over life events is a common precursor (

Bentall & Fernyhough, 2008) and a consequence of psychosis (e.g.

Birchwood, Mason, MacMillan, & Healy, 1993). Control of one’s life as a goal or outcome is an essential part of recovery from psychosis (

Gumley & Schwannauer, 2006). However, throughout the literature, it is implied that what people seek to control is their behaviour, and in line with this, targets within therapy commonly focus on behavioral change; for example, managing aggression or increasing activity levels or improving social skills and assertiveness. Contrary to this, PCT specifies that people do not directly control their behavioral output but control their perceptual experiences (input). Research based on simulation and modelling has demonstrated this (e.g.

Marken, 2001;

Powers, 2008). The term “perceptual experience” refers to an individual’s experience of the world and in PCT, a person’s perception is his objective reality. For a simple, everyday illustration, imagine driving a car to work. Even though the journey is the same each day, the driving behavior

must be different each time, depending on what is going on in the roadway. If one were to control

behaviors, such as turning the steering wheel in the same way, lifting a foot off the gas at precisely the same moment, and applying the brake as done the morning before, one would never reach work and would surely end up in the Emergency Department! Instead, what is controlled is the

perception of how the car is travelling. For example, the sense of being the right distance from other cars, the position on the road, and how fast the care travelling. This idea is a diversion from theories utilized within CBT and psychodynamic approaches, where it is assumed that people use perception to control behavior.

In PCT, responses are aimed at minimizing any disturbance the environment creates on the preferred states individuals are trying to maintain. In other words, control the effect behaviours have on the way the environment is experienced, not the behavior itself. We compare a current experience (perception) to the preferred state and then act to reduce any discrepancy between the two. Discrepancy is experienced as psychological distress. Goal achievement can be considered to have occurred when what is perceived matches the imagined goal. This concept may resemble, in psychodynamic terms, having achieved “perceptual identify” in conformance with a wish or goal.

Within PCT, control is the process of “perceiving, comparing and acting” and is referred to as a

control system, based on negative feedback (

Powers, 2008;

Carey, Mansell & Tai, 2014). We each have countless control systems that are interconnected and organised hierarchically. Lower levels of the hierarchy relate more to specific control processes involving concrete actions—

how we do things—and higher levels consist of personal values and principles—

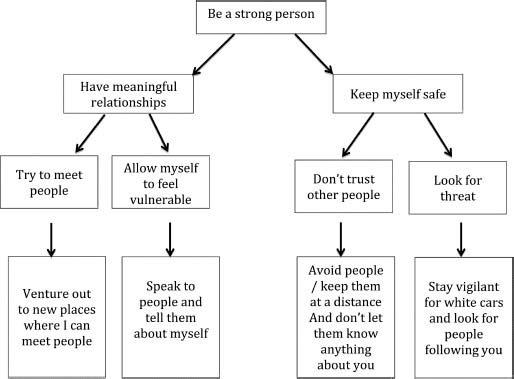

why we do things. For example, a higher level goal such as “to be a good person” (the why), will have many lower level goals and actions (the how) that serve the higher level goal, for example, buying friends gifts, remembering the birthdays of family members, and opening doors for strangers. What might appear as varied or random behavior is a lower-level process at work, which is instrumental for achieving a preferred state. Therefore, we can never really know what someone is really trying to do—what his goal is—by merely observing his behavior. This is particularly important to remember in the context of psychosis, where behavior might appear extreme, erratic, and unintelligible. From a PCT perspective, psychoses and all mental health problems, are part of a continuum with the normal realm of behaviour. In MOL, symptoms of psychosis are understood as functional within the context of an individual’s efforts to control an important goal within his life. Extreme behaviors are more likely when there is extreme discrepancy between a preferred state and a current experience. To use a case example, Ellen had persecutory ideas about people driving white cars. She believed they were following her with malevolent intent. Ellen had a life history of trauma, and two important preferred states (goals) for her were, firstly, to feel safe, but secondly, to be able to strive towards safety without feeling reliant on others. Within the context of her persecutory beliefs, Ellen was engaging in lower level actions of monitoring the presence of white cars and walking past her house to check it was safe before entering. This served the function of bringing her closer to her preferred state of keeping herself safe without relying on other people. The example of Ellen’s problem as a hierarchical control system is illustrated in

Figure 1. Obviously, psychotic experiences like Ellen’s, and associated behaviors, have many negative consequences, and the next section of this paper will address in more detail why these experiences can lead to such extreme distress. The important point here is that psychotic experiences can be understood as part of a normal control process where individuals’ are trying to make their experiences fit with how they want their world to be.

People have numerous preferred states to maintain, and what we consider to be healthy functioning is contingent upon successfully managing to balance these different goals simultaneously (

Carey, 2008b;

Mansell & Carey, 2009). Integral to using MOL when working with people experiencing psychosis is to convey a normalizing approach, whereby symptoms are understood as being a consequence of some other problem in the person’s life and that the mechanisms leading to psychosis are not abnormal. This is consistent with Romme’s and Escher’s cognitive behavioral approach for psychosis (

Romme & Escher, 1994;

Romme, 1998) and in keeping with a psychodynamic perspective whereby seemingly unusual beliefs and behaviours are regarded as meaningful expressions of a psychotic person’s psychic life.

The emphasis within MOL is on identifying and working with a patient’s underlying distress as opposed to their symptoms. Method of Levels aims to do this by increasing a patient’s awareness of his preferred states and assisting the patient in achieving the associated goals to increase a sense of control. Understanding how problems with control arise is, therefore, important to conceptualizing and thus directing what the MOL therapist must do.

Conflict & Reorganization

The mechanisms through which control is lost for people with psychosis are no different to how control is lost for anyone. For example, physical or organic damage may compromise a control system, disrupting the process of comparing a current perception to a preferred state and acting to reduce the discrepancy between the two. Also, situational factors may be so extreme that an individual’s efforts to minimise the environmental disturbances on what he is controlling could be overwhelmed. There is a wealth of evidence, for example, that people with psychosis are more likely to have experienced significantly disrupting life events and were exposed to chronic difficult life circumstances (

Varese, Smeets & Drukker, 2012). However, the most common cause of loss of control is conflict (

Carey & Mullan, 2008;

Carey, 2008;

Powers, 2005). The concept of conflict is not unique to PCT. Bringing sides of conflict that a person is not fully aware of into consciousness is a fundamental goal of psychodynamic interpretation. Also, conflict such as cognitive dissonance (

Festinger, 1962), may be targeted as a source of distress within CBT. From a PCT perspective, every day functioning for any person involves trying to reach countless preferred states, or goals, simultaneously. Conflict between different control systems is inevitable. Perceptual control theory regards the distress and discomfort of a dilemma—or having a difficult decision to make—as something entirely normal and something that anyone can relate to. For example, wanting to accept a much-desired job some distance from home whilst also wanting to spend more time with one’s family, or, wanting to be honest with someone but not wanting to hurt their feelings. Resolution of conflict and re-establishing control usually happens spontaneously through a process of reorganization, which is described in the next section of this paper. However, when conflict remains unresolved, the consequence is chronic loss of control, which can result in mental health problems, including psychosis. Ongoing conflict arises from two or more control systems that are interrelated pursuing incompatible preferred states—so that reduction of discrepancy within one control system increases the discrepancy for the other. For example, the earlier case of Ellen wanting to avoid relying on other people had the impact of bringing her further away from a co-existing preferred state of having meaningful and trusting relationships with others. Ellen experienced ongoing conflict between wanting to achieve a sense of safety, which she strived for by being hypervigilant of potential threat and avoiding it, but also wanting to be able to lead a normal life in which she could go to new places and manage potential threat. She also wanted to feel self-reliant and tried to achieve this by keeping people at a distance; on the other hand she wanted to engage in meaningful relationships without feeling vulnerable. Subsequently, her behaviour fluctuated and appeared to observers as chaotic as she oscillated between preferred states, trying to reach incompatible goals. This resulted in Ellen’s not reaching any of her preferred states, and this loss of control caused considerable her psychological distress. Often people are unaware of both sides of their conflicts. For example, Ellen was aware of her desire to have meaningful relationships in her life, but was less aware of the motivation behind her avoidance of relationships—the avoidance of feeling vulnerable.

Another way of thinking about conflict is in terms of relativity. Particular thoughts, experiences, or feelings are problematic relative to coexisting thoughts, experiences, or feelings.

Carey (2009) suggested that “the value we attribute to a particular thought is

always determined by the way in which it measures up to other thoughts, ideas, goals, and beliefs that we have” (p. 168). For example, if Ellen’s need to feel safe was a preferred state held in isolation, it may not have been distressing. However, the problem arises because she also wants to be able to tolerate feeling vulnerable so that she can pursue relationships and expose herself to situations and activities that could feel more threatening.

Another case example is that of Brigit, who sought help for distressing voices that told her she was to blame for abuse she experienced earlier in her life. For Brigit, an isolated belief that she was to blame for her abuse may have been fairly benign had it not been for the co-existing beliefs and standards she held. Brigit believed she should be able to stand up for herself, to prevent bad things from happening to her, and to see herself as a strong and capable person. This is consistent with evidence that for people who experience hearing voices their distress is often associated with the content of the voices being incongruent with the values to which they adhere, leading to cognitive dissonance. This is thought to contribute to internally generated phenomena that may be misattributed to an external source (

Baker & Morrison, 1998). From a PCT perspective, the degree to which psychotic experiences are problematic or distressing is relative to the preferred states held by an individual.

The psychotic experience is functional for one preferred state but may be problematic and appear dysfunctional in relation to other important preferred states. From this perspective, a paranoid belief, or an unwanted perceptual experience, such as hearing a voice, or a distressing belief, such as “I am worthless,” are not abnormal, but are attempts to bring the individual closer to a preferred state held at a higher level. This is in contrast to techniques in CBTp where specific thoughts and beliefs are targeted as maladaptive and generating alternative ways of thinking are encouraged. Method of Levels therapy aims to help develop awareness of preferred states and different sides of a conflict as a means of generating new potential solutions to balancing preferred states and achieving different goals simultaneously, through a process known as reorganization.

Reorganization as the Mechanism of Therapeutic Change

Perceptual control theory states that when there is a discrepancy between a preferred state and the current state, random trial and error changes are made to the organization of control systems. This results in changes to how behaviour is produced as opposed to what behaviour is produced. This mechanism of change is a basic, innate learning process known as reorganization (

Marken & Carey, 2014). There is no decision-making, planning, or analysis of the pros and cons of the changes that occur as part of reorganization, or the behaviours involved. The process is much less complex and consists of generating a change and monitoring the outcome of that change. Reorganization is incessant, and it continues to generate random changes unless discrepancy reduces, in which case the change remains. Change occurs within a hierarchical system of goals and intentions, as opposed to specific preferred states. As this system interacts with ever-changing environments, the reorganization is likely to be constant. Because the very nature of reorganization is creation of immediate change, the more creative or tangential an idea, the more potential it has to reduce the discrepancy. Therefore, when in distress, people are more likely to experience ideas that appear bizarre, extreme, or out of the ordinary. However, if changes brought about by reorganization are generated too quickly, sufficient monitoring of the effect cannot occur, and control is lost. Similarly, changes that are generated too slowly will be ineffective at restoring control. Problems with the timing of reorganisation could result in action that is incongruent with an individual’s environment and might play an important role in the development of psychosis (

Carey, Mansell, & Tai, 2015).

Powers (2008) outlined that reorganization takes place wherever mental awareness—or consciousness—is focused, and therefore our attention is naturally drawn to areas of discrepancy. From a PCT perspective, what makes any psychotherapy effective in creating therapeutic change is whether it facilitates the mobility of awareness within the hierarchy of interrelated control systems so that reorganization can occur at the right level (

Carey, Kelly, Mansell, & Tai, 2012). The importance of shifting awareness is evident in other therapies, although the methods for achieving this might be somewhat different to MOL. For example, CBTp interventions increasingly focus on mobilizing attention within treatment, for example, mindfulness (

Chadwick, Newman Taylor, & Abba, 2005) or metacognitive training ([MT];

Moritz & Woodward, 2007). Also, in PA, a central part of treatment involves bringing the unconscious into consciousness, whereby conflicting wishes are integrated into current awareness through the therapist’s interpretations (

Freud, 1955).

In PCT, the important part of therapy is considered to be those methods that facilitate a patient having increased control over what is important to them, thus reducing their psychological distress. Any therapeutic technique or strategy can be considered effective if it helps a person sustain attention at the level required for reorganization to take place so that new perspectives, thoughts, insights, beliefs can be generated. Method of Levels focuses exclusively on creating the conditions most likely to help this process occur, which in practice involves the therapist closely following the lead of the patient. If one particular strategy does not work for a patient, the strategy is changed, as opposed to the patient needing to change. There is recognition that what works for one person might not be experienced in the same way by someone else. Subsequently, many elements considered to be important in other therapies, such as structured assessments and history taking, specific methods for alliance building, making interpretations, or giving homework, for example, are not considered as requisite within MOL. Indeed, for some patients, these methods might even “get in the way” of reorganization. For example, it is generally accepted that positive therapeutic alliance is associated with good therapeutic outcome (

Orlinsky et al., 2004). However, the specific behaviours required from the therapist to foster good alliance might vary depending on the individual patient. From a PCT perspective, what is important about the therapeutic alliance is the extent to which the behaviour of the therapist facilitates the patient being able to talk about a problem in a focused way without feeling inhibited. Focusing on a problem in this way is likely to elicit a degree of emotional discomfort for the patient and, as such, some patients could perceive therapeutic alliance as lower in such emotionally challenging sessions, even though the “helpfulness” of the encounter might be rated as high. Therefore, in MOL, specific techniques for directly targeting therapeutic alliance are not employed, but the therapist might directly ask the patient about their experience of the therapeutic process. It is recognized that distress can only be understood from the perspective of the patient, who has the capacity to generate his or her own solutions. Therefore, what is emphasised is creating the conditions required by that individual patient to focus on their problem, through some form of external expression, in order to facilitate reorganization.

Reorganization is not something that one can just make happen in a planned, systematic manner. It is a process that keeps on occurring spontaneously unless a person reaches a point of equilibrium in their life and is able to control the things that are important to them. Method of Levels aims to keep patients focused on their problem long enough to develop awareness of their conflict and generate new perspectives, which can increase the chances of them making changes where required (

Carey, 2011). Each individual’s distress reflects a unique conflict requiring novel and often unpredictable solutions.

For example, Ellen’s conflict of wanting to keep people at a distance to feel less vulnerable while also wanting to have meaningful relationships would be unlikely to resolve by merely choosing one option over the other. In reality, once Ellen was aware of both of these preferred states, she decided there were times when she would be more willing to take calculated risks to develop relationships and other times when she felt it might be more appropriate to keep her distance. She spent some time working out how to balance both goals, and solutions were often situation specific. Her conflict between seeking safety through avoidance and wanting to venture out resembled her conflict around relationships. Ellen was also able to understand some of her psychotic experiences in relation to her conflict. When she asked to describe how her experience of being followed by people in white cars was a problem, she explained how it prevented her from being able to venture out or develop relationships. However, she also became aware of how her experiences also served to keep people at a distance and lead her to seek safety. As Ellen began to find new ways of managing her conflicting preferred states, her experience of being followed began to rescind, which from a PCT perspective reflects reorganization.

The Method of Levels (MOL)

To facilitate reorganisation, MOL aims to help patients express and sustain their focus on a problem area. Focusing needs to be held for long enough to bring into awareness a range of emotions and thoughts about the problem and to shift attention to higher-level goals and values. To achieve this, an MOL therapist has only two goals. The first is to create the conditions whereby a patient is able to talk about a problem (any area of life that is currently not the way he would wish it to be). Method of Levels is not a coercive intervention, and thus depends on the willingness of a patient to talk, even if this is about ambivalence over attending therapy! For example, someone who attends an appointment only because his key worker threatened hospitalization if he did not, may not perceive himself as having a problem needing discussion. He might, however, be willing to discuss the experience of having been given an ultimatum, whether the difference in opinions bothers him or why hospitalization is something he would choose to avoid.

The second goal in MOL is to look out for an indication that a patient has experienced a background thought, as he was discussing a problem, and to draw his attention to this. This is specifically to redirect attention so that his exposure to parts of the problem that would otherwise have only been attended to fleetingly is increased. Emphasis is placed on the way in which the patient thinks about the problem as opposed to drawing out details related to the content of what the person says or other random free associations. If the background thought is not deemed by the patient to be relevant to the problem, it is dismissed. This is very much an experiential process aimed at developing awareness of higher-level goals and conflicts. Potential solutions to problems can be discussed in therapy but are often generated spontaneously and might not necessarily occur during the therapy session, but later. The time taken to resolve conflicts will vary between patients. Logical problem solving and advice are of limited value, and even potentially counterproductive, as it is likely to encourage the person to focus on one side of a conflict rather than developing multiple perspectives. This process of noticing background thoughts might bear resemblance to the process of eliciting multiple cognitions and emotions in CBTp. In PA, the techniques of eliciting free association may look similar. However, in MOL, background thoughts specific to the problem are regarded as instrumental to helping patients manoeuvre their awareness to higher levels, thus increasing chances of reorganization occurring in the right place.

The two goals of MOL therapy may appear simple, although what a therapist does to implement these goals may look considerably different depending on the patient. The three principles of control, conflict, and reorganization are used as a framework in which to understand behaviours that might otherwise be assumed to be part of a psychotic symptom, or of a patient being resistant, non-compliant, or avoidant. For example, Brigit often gave tangential replies to the therapist’s questions and looked away when sensitive topics were raised. Her behaviour may have been considered evidence of thought disorder and also her being avoidant or disengaged. However, Brigit’s preferred states included being able to stop bad things from happening and also being a strong person. Her tangential replies were attempts at providing accounts of times when she had done something she was proud of and her avoidance of eye contact was so the therapist would not see how upset she was and perceive her to be strong. An MOL therapist remains respectful that all people are acting to maintain a preferred state and one cannot know what any single patient is doing by observing his actions. The emphasis is on asking them directly about what they are controlling, as opposed to making interpretations or assumptions.

It is of the upmost importance that a patient feels able to talk openly and honestly about a problem and his immediate experiences, verbalising the stream of conscious thoughts he experience as the thoughts occur. At the start of a session, the therapist begins by asking the patient what he would like to discuss. The therapist might begin simply by asking, “What would you like to talk about today?” “Is there a problem area you would feel able to talk about to today?” It is important that the patient generates the focus of the session. The therapist then works to retain the patient’s attention by asking detailed and curious questions. Frequently, people experiencing psychosis do not want to talk about psychotic symptoms, but other problems, such as getting a job, or finding a relationship, or the fact that they are only at the therapy session because their key worker arranged it. For example, if a patient responded with “I don’t know what I want to talk about,” the therapist might ask “Does it bother you that you don’t know?” or “Is it that you don’t know how to say it?” or even “What is it like not to know?” A vignette Ellen’s case can be used as a further example of how a session might appear:

Therapist: “What would you like to talk about today?”

Ellen: “Well, I’m not quite sure because I don’t really want to talk about things that have happened”

Therapist: “You don’t have to talk about anything that you don’t want to. Would you feel able to tell me why you don’t want to talk about things that have happened?”

Ellen: “Because when I talk about ‘it,’ things just come into my mind.”

Therapist: “OK. Well I don’t have to ask you about “it.” Could you talk about what bothers you about “things” coming into your mind?”

Ellen: “Well, thoughts, images and memories are trying to get into my head. I don’t want to think about that. It’s too scary. I want to push them away and put a lid on them and not have to think about what happened.”

Therapist: “Are you pushing them away and putting a lid on them now as you speak?”

Ellen: “Yes I am pushing them away”

Therapist: “Where are you pushing them away to?”

This excerpt demonstrates how the therapist does not lead Ellen to speak about things she does not wish to but maintains focus on the process of Ellen’s thinking. It is not necessary for Ellen to recall details regarding her past experiences. Instead, the therapist maintains Ellen’s focus on the present-moment experience of past events. The focus is on how Ellen currently thinks about and evaluates these thoughts in the here and now. For example, the therapist might ask, “As you are speaking now are thoughts trying to get into your head?” or “If you push ‘it’ away, what kind of thoughts would be okay to have in your head?” or “When you push the thoughts, how long do they stay away?” If necessary, the patient may choose to use a word or phrase to refer to an experience she did not want to discuss. In the example, Ellen chose to refer to her past traumatic experiences as “It”. The MOL therapist refrained from making assumptions about what the patient was saying and did not offer interpretations. Therefore, the therapist refrained from making comments that would traditionally be considered empathic, such as “that must be difficult for you” because might be inherently assumptive and may stifled Ellen’s discussion of her problem. What is important is that the therapist helps the patient express and focus on current experiences. An MOL therapist utilises, almost exclusively, a curious but sensitive questioning style, speaking at a pace that matches the patient’s, using short, simple, single questions. It is always acknowledged that the therapist cannot know what the patient is experiencing. What the patient says is a form of verbal behaviour that may not divulge much about the internal experience. Therefore, therapist uses terminology generated by the patient and asks what certain words mean. For example, the therapist could have asked “what made you choose the word scary to describe the thoughts?” The focus during therapy is always on the here and now. Patients are encouraged to express immediate experiences in whichever modality they occur, such as visual imagery, or verbal forms. Even when the problem relates to a past event, it is the current evaluation or experience of the problem, in the present, that is significant. Questioning around experiences as they occur is not reliant on memory, recall or any post-hoc analysis of metacognitive processes. As such, this can be a particularly useful approach when working with an individual who has difficulty expressing himself, and appears thought disordered when describing particularly unusual perceptual experience (

Tai, 2009). To promote in-the-moment experiential and evaluative processing, questions can be quite literal. For example, Brigit described how she often worried about what her voices said and tried to “sweep her worries under the carpet the therapist pursued the visual metaphor and asked, “How far under the carpet do you have to sweep them?” Conversations about lumps under carpets might seem bizarre but the aim is to keep a patient focused on the experience long enough to process a range of thoughts and feelings about it.

A patient will have a range of background thoughts as he talks about a problem. There are usually nonverbal signs such as a flicker of a smile, a stutter, pauses mid-sentence, or a change in intonation, that indicate thoughts are momentarily popping into consciousness. In MOL these are known as disruptions, and the therapist asks about these as a means of drawing attention to the background thoughts. For example, the therapist might ask, “Did something occur to you when you just paused?” or “What made you stress the word “push them away”?” While drawing attention to nonverbal behaviours in this way is something that CBT therapists may do, this technique is not used routinely in CBTp. In PA free association and identifying resistance in the free flow of patients’ thoughts, used with the rationale of drawing out deeper level conflicts may appear somewhat similar. From a PCT point of view, background thoughts are used to help develop awareness of higher-level processes, so that as the patient’s awareness moves to preferred states, goals, and values, conflicts are revealed.

If the patient reveals that the disruption is unrelated to the problem being discussed, then the therapist encourages him to continue talking and maintain his focus on the original problem. Sometimes a patient may go off on a tangent, in which case the therapist could ask, “How does that connect to what you were just saying?” While the therapist’s goal is to track how the patient’s thinking evolves and awareness develops, the therapist must keep patient’s attention on the problem as opposed to passively following the discussion off on tangents. In practice, striving to achieve the two goals of MOL requires the therapist to behave rather differently depending on the presentation of the patient. For example, a patient who talks a lot and wanders off topic may require frequent interruption to ask about disruptions, whereas someone who speaks slowly and needs to think over what he says may find that too many questions about disruptions interferes with his reflecting process. The skill of an MOL therapist is in promoting the mobility of a patient’s awareness to the different levels of what he is experiencing without “getting in the way” of the natural fluidity of the thinking process (

Carey, 2005). The MOL Self-Evaluation Form (see Carey & Tai, 2014) provides a scale in which the therapist’s adherence to MOL principles can be assessed.

The following example from Ellen’s therapy provides further illustration of MOL therapy and illustrates asking about background thoughts and redirecting attention to higher levels of awareness:

Therapist: “How does it sound to hear yourself describe all the effort it takes to push thoughts away?”

Ellen: “Well, I …. urrggh [Ellen sighs]”

Therapist: “What made you sigh?”

Ellen: “I just feel helpless. I don’t feel like I’ve got control … and being in control is something I do. It’s absolutely what I do.”

Therapist: “And you are emphasising the word ‘absolutely’?”

Ellen: “Well I have to be in control.”

Therapist: “Why is being in control important?”

Ellen: “I need to be in control so that I can be protected and keep my walls built strong … otherwise someone could hurt me … I’m vulnerable … I can’t be hurt.”

Therapist: “How do you keep your walls strong?”

Ellen: “Well not talking about ‘it’ … and if I’m outside and there’s a car … I see a car parked on my street, then I keep walking past my front door so the people in the car don’t know it’s my house … and … I …” [Ellen looks away].

Therapist: “What crossed your mind just then?”

Ellen: “That it all makes me feel so helpless.”

Therapisty: “The things you are doing to keep your walls strong make you helpless?”

Ellen: “Yes. But I can’t let people know what I’m doing.”

Therapist: “Is that because you said someone can hurt you?”

Ellen: “Yes, I can’t be vulnerable.”

Therapist: “How does it sound to hear yourself put it that way?”

Ellen: “Accurate … I can’t be too vulnerable”

Therapist: “How much vulnerability is too much?”

In this session, Ellen continued to talk about how she found any vulnerability difficult to deal with, and she disclosed her immediate feelings of vulnerability within the therapeutic context and fears about trusting the therapist. She scheduled her next three sessions with approximately three or four 4 weeks between each one, returning when she was particularly distressed about white cars or her beliefs that people were following her and she wanted help. She reported that her sense of vulnerability had increased, although her ability to speak freely with the therapist also increased over that period. Ellen chose to speak more about her desire to develop trusting relationships in her life, which led to her reflecting on the abusive experiences she had as a child and how she had never in her life experienced a trusting relationship. She reported increased awareness of how thinking about her childhood increased her sense of vulnerability and desire to pull away from others. During her fourth session, when speaking about her expectations of others to let her down, Ellen described a “light-bulb” moment; she identified how keeping her distance from others was as important to her as having meaningful relationships. At this point, Ellen scheduled four appointments over a two-week period. She wanted to speak about current situations in her life, and in therapy she described the conflict between wanting to be close to people and wanting to be alone so that she would not feel vulnerable. During this time, her preoccupation with cars and being followed reduced, and she began to engage with family members and friends again. Ellen attended therapy for another six sessions during a four-month period. She spoke about everyday encounters with people that reflected her conflict. The discussion usually centred on problem-solving a specific predicament. In the fourteenth session she described how avoiding white cars and believing she was being followed meant that it was almost impossible for her to meet new people or go out with people she did know. In subsequent sessions she talked very little about feeling she was being followed and reported that this now bothered her less. Ellen then decided to enrol on a college course, and after a total of 18 sessions over 12 months, she felt she no longer required therapy.

Practicalities of Delivering MOL for Psychosis

The structure of MOL therapy maximises the amount of control a patient has within the therapeutic process. In line with the PCT perspective that reorganization is an idiosyncratic process with a time scale that varies vastly between people, appointment scheduling in MOL therapy is flexible. Patients are encouraged to choose the number, frequency, and duration of their appointments. For example, a patient can contact the service to arrange appointments as and when they wish. Many practitioners have concerns that this is not feasible within increasing service restraints regarding resources, or that some patients will fail to engage with services, or high-risk patients may slip through the net. However, flexibility can still be offered within service constraints, so patients might have an upper limit on the number of sessions they have, or limits as to how long the session is and how frequently they can schedule. In reality, there is evidence that patients only attend the appointments they want anyway until they have reached a good enough level of change (Stiles, Barkham, Connell, & Mellor-Clark, 2008). There is a range of evidence to suggest that the number of sessions patients choose to attend is far fewer than therapists expect (e.g.

Boisvert & Faust, 2002). Also, in practice, it has been demonstrated that patient-led appointment scheduling has the potential to be much more efficient than traditional fixed-pattern programmes of treatment (

Carey et al., 2013;

Carey, 2011) and it can be highly suited to people with psychosis and it may increase the likelihood that patients will engage in treatment (

Tai, 2009). Research has demonstrated that patientled appointment scheduling has yielded positive benefits to services, including reduced waiting times, increased access to psychological therapy for more patients, and being highly acceptable to patients (

Carey et al., 2009;

Carey & Mullan, 2007,

2008;

Carey et al., 2013).

The author of the current paper has delivered MOL to patients experiencing psychosis in a range of community and inpatient settings, including acute psychiatric inpatient services and psychiatric intensive inpatient units where the duration of stay was extremely variable. For inpatient settings, 30-minute slots were made available to patients throughout the week by using an open access diary, enabling patients to choose when, how often, and for how long they attended therapy. All inpatients admitted to the service were offered psychological therapy, which could be targeted at any problem of their choice. This was offered in addition to usual psychological components of their care plan. On average, within a 12-month period, more than 50% of admitted patients utilised at least one drop-in session. Patient feedback (verbal and service feedback questionnaires) demonstrated that drop-in therapy was feasible, acceptable to inpatients, and addressed relevant psychological needs. It can be a very efficient use of limited resources. Assessing and monitoring risk within MOL occurs as it would in any usual clinical practice. However, with patient-led appointment scheduling, it would be possible to agree a maximum period of time of no-contact before the therapist contacts the patient. Alternatively, for therapists who are part of a team of professionals working with an individual patient, it might be possible for other team members to monitor risk in order to facilitate a specific therapy component to the patient’s overall care plan. This can be beneficial in instances where mixing psychological therapy with more general aspects of case management can have negative consequences on the overall engagement of a patient.

Training to deliver MOL interventions is usually in the form of accessing treatment manuals (e.g. (

Carey, 2005;

2008a; Mansell et al, 2012;

Carey et al., 2015;), workshop attendance, and supervision. It is highly recommended that supervision includes the use of role-play practice of MOL, feedback on video-taped sessions, and observation of therapy delivered by experienced practitioners. Further information and training resources are available at

www.methodoflevels.com.au and

www.pctweb.org