Patient Extratherapeutic Interpersonal Problems and Response to Psychotherapy for Depression

Abstract

Objectives:

Methods:

Results:

Conclusions:

Highlights

Methods

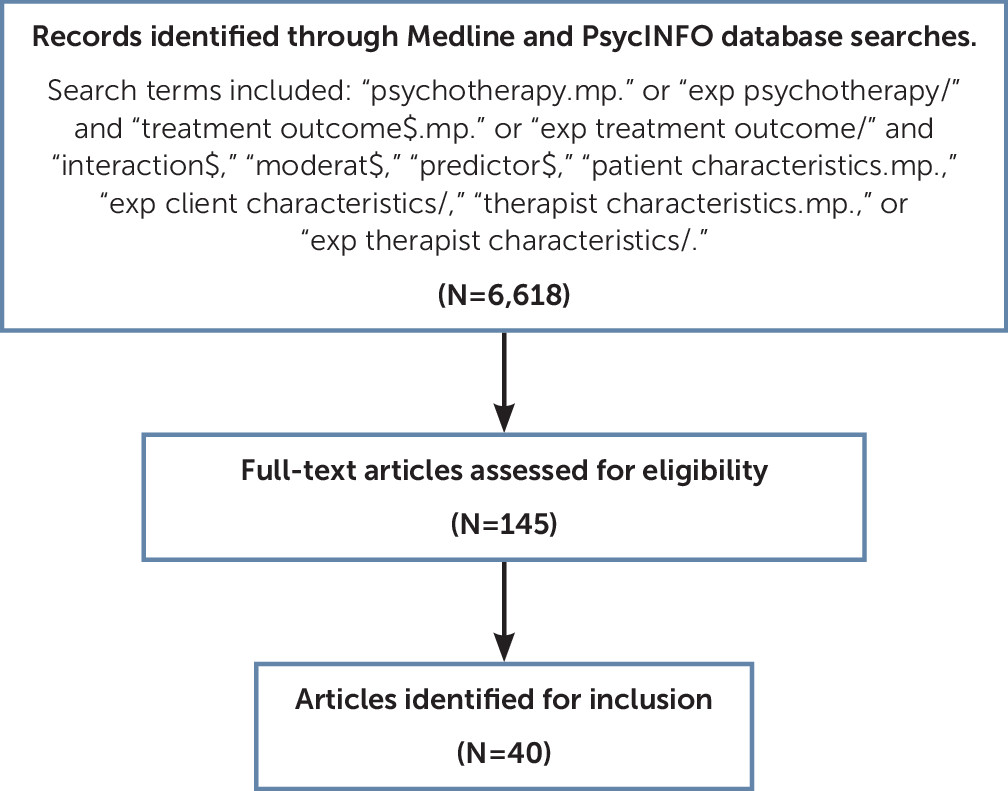

Search Strategy

Inclusion Criteria

Identification of Studies and Abstract Screening

Data Synthesis and Analytic Approach

Results

| Study | Sample | Type of psychotherapy | Depression outcome measure and criteria | Interpersonal predictor | Major findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capacity to engage with others | |||||

| Access to social support | |||||

| Moos and Cronkite, 1999 (29) | 313 patients with major depressive disorder | Unspecified (range of treatments in different outpatient settings) | Remission=DSSI <1 SD above baseline mean of nondepressed control group and no hospitalization for depression | HDL social functioning items | Patients who at baseline reported less time spent with friends were at greater risk of a chronic course of depression following treatment. Specifically, among participants who reported no time spent with friends, 55.4% obtained remission or partial remission from depression compared with 74.9% of those who did spend time with friends (p<.001). |

| Meyers et al., 2002 (30) | 165 patients with major depressive disorder | Unspecified (range of treatments in different outpatient settings) | Remission=HRSD-17 score ≤6 | Duke Social Support and Stress Scale | Social support was not a significant predictor of recovery from depression. |

| Coffman et al., 2007 (31) | 88 patients with major depressive disorder | Cognitive therapy or behavioral activation | Extreme nonresponse=BDI-II ≥31 | Qualitative analysis of session content | Patients experiencing more problems accessing their primary support group (e.g., because of a death in the family, divorce, estrangement, or health problems) were more likely to demonstrate extreme nonresponse to cognitive therapy but not to behavioral activation. Analysis was conducted as part of an assessment of randomization. The effect size for this relationship was not reported. |

| Bernecker et al., 2014 (32) | 95 patients with major depressive disorder | IPT | BDI-II, HRSD-17, GAF | SSQ-B | At a trend-level (p<.10), increase in satisfaction with social support was associated with lower BDI-II. |

| Constantino et al., 2013 (33) | 70 patients with primary diagnosis of major depressive disorder | IPT | Remission=criterion 1: BDI-II ≤14.29 and change in BDI-II ≥8.46 pts from baseline. Criterion 2: BDI-II ≤10. | SSQ6 | Social support was not a significant predictor of remission from depression. |

| Lindfors et al., 2014 (34) | 326 patients with anxiety or mood disorders | Short-term solution-focused therapy, short-term psychodynamic therapy, or long-term psychodynamic therapy | SCL-90-GSI | BISSI | Patients reporting lower levels of pretreatment social support (i.e., network size, satisfaction, and perceived availability of emotional support from friends and family) showed greater symptom reduction (40.0%) in short-term therapy than in long-term therapy (26.3%) at the 12-month follow-up (p value not reported). However, the difference was no longer significant at 24- and 36-month follow-ups. |

| Marital status | |||||

| Meyers et al., 2002 (30) | 165 patients with major depressive disorder | Unspecified (range of treatments in different outpatient settings) | Remission=HRSD-17 score ≤ 6 | Marital status | Patients who were married were more likely to experience early recovery from major depressive disorder (OR=2.4; 95% CI=1.1–5.3; p=.03). |

| Fournier et al., 2009 (35) | 180 patients with major depressive disorder | Cognitive therapy | HRSD-17 | Marital status | Patients who were married or cohabiting had lower depression scores at end of treatment (t=–3.13, df=156, p=.002). Additionally, for married or cohabitating participants, cognitive therapy resulted in lower depression scores following treatment than antidepressant medication (Cohen’s d=1.04+.58 [95% CI], p<.001). |

| Jarrett et al., 2013 (36) | 410 patients with recurrent major depressive disorder | Cognitive therapy | Nonresponse=met DSM-IV criteria for major depressive disorder and/or HRSD-17 >12 | Marital status | Marital status was not predictive of treatment response. |

| Bastos et al., 2017 (37) | 272 patients with moderate depression | Long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy | BDI | Marital status | Marital status was not predictive of treatment response. |

| Lemmens et al., 2016 (38) | 117 patients with depression; 58% met criteria for severe depression (BDI-II ≥29) | Cognitive therapy or IPT | BDI-II | Marital status | Marital status was not predictive of sudden gains that were predictive of treatment response (44.4% of the sudden-gain patients met criteria for remission [BDI-II <9] versus 25.0% of those without sudden gains χ2=4.21, df=1, p=.04). |

| Menchetti et al., 2014 (39) | 287 patients with major depressive disorder (136 received interpersonal counseling, 139 received SSRI) | Interpersonal counseling | Remission=HRSD score ≤7 | Marital status | Unmarried patients were more likely to remit from therapy (73% unmarried vs. 57% married) (p value was not provided). |

| Barber and Muenz, 1996 (40) | 88 patients with major depressive disorder | Cognitive therapy and IPT | BDI-I, HRSD-17 | Marital status | A marital status by treatment interaction existed where IPT was relatively more effective than cognitive therapy with single or separated or divorced patients, whereas cognitive therapy was relatively more effective than IPT with married or cohabiting patients as measured by the HRSD (β=8.10, p=.0021) and on the BDI (β=12.56, p=.0023). |

| De Bolle et al., 2010 (41) | 567 patients with major depressive disorder | Supportive, cognitive-behavioral, and psychodynamic therapy | MADRS | Marital status | Patients who were divorced or separated were more affected by therapeutic alliance (HAQ-I) on outcome than married patients (Cramér’s V=.11; p<0.01). Marital status as a moderator of the effect of therapeutic alliance on outcome was not significant when comparing married patients to widow(er)s or single patients. |

| Capacity to navigate relationships | |||||

| Interpersonal difficulty | |||||

| Meyers et al., 2002 (30) | 165 patients with major depressive disorder | Unspecified (range of treatments in different outpatient settings) | Remission=HRSD-17 score ≤6 | IIP | A higher percentage of patients with interpersonal problems above the cutoff score for personality dysfunction (67.5%) did not recover from major depressive disorder than those with interpersonal problems below the cutoff score for personality dysfunction (32.5%; p=0.03). Patients who recovered from major depressive disorder showed a trend in scoring higher in social functioning (SF-36=53.1) than patients who did not recover (SF-36=43.9; p=0.07). |

| Connolly Gibbons et al., 2003 (42) | 201 patients with major depressive disorder (50%), generalized anxiety disorder (33%), avoidant personality disorder (35%), obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (19%), dysthymia (17%), social phobia (27%), simple phobia (12%), and anxiety disorder not otherwise specified (23%) | Cognitive therapy or psychodynamic (expressive/supportive) therapy | BDI-I | IIP | Greater interpersonal difficulties were associated with greater depression at session 10 (r=0.34, p<0.05). |

| Renner et al., 2012 (43) | 523 patients with recurrent major depressive disorder | Cognitive therapy | Change in HRSD-17 | IIP | Elevated baseline IIP interpersonal distress scores were associated with more symptoms (F=24.82, df=1, 521.12, p<.01) throughout treatment. |

| Jarrett et al., 2013 (36) | 410 patients with recurrent major depressive disorder | Cognitive therapy | Nonresponse=met DSM-IV criteria for major depressive disorder and/or HRSD-17 >12 | SAS-SR, DAS-A, IIP | Patients self-reporting more dissatisfaction with their social roles were less likely to respond to cognitive therapy after the analysis was controlled for pretreatment depression symptoms (OR=.517, 95% CI=.32, .83). Self-report rating of statements related to relationships on DAS-A were not significantly different between responders and nonresponders (F=.09, df=1, 395, p=.77). There was a trend-level difference on interpersonal difficulty based on the IIP mean score between responders and nonresponders, with nonresponders endorsing more interpersonal difficulty (F=3.96, df=1, 404, p=.05). |

| Altenstein-Yamanaka et al., 2017 (44) | 144 patients with major depressive disorder | CBT or exposure-based cognitive therapy for depression | BDI-II, IDS-C, SCL-9 | IIP-32 | Pre-post change in IIP distress was positively associated with pre-post change in BDI-II (r=.181, p=.047) and IDS-C (r=.320; p=.001), but not with pre-post change in SCL-9 (r=.133; p=.145). IIP distress did not predict symptomatic change from termination to follow-up. |

| Denton et al., 2010 (45) | 171 patients with chronic major depressive disorder | Cognitive-behavioral analysis system of psychotherapy | IDS-SR30 <15; equivalent to HRSD <8 | MAS | Patients with dyadic discord at baseline had lower remission rates (34.1%) compared with those without dyadic discord (61.2%) in all three groups (p=0.0004): psychotherapy, medication, combined treatment. |

| Whisman, 2001 (46) | 64 patients with major depressive disorder | CBT and IPT | Change in BDI-I, change in HRSD-17 | MAS | Patients with better pretreatment marital adjustment had lower depression scores at end of treatment (r=0.41, p<0.01) and 6-month follow-up (r=0.27, p<0.05) on the HRSD but not on the BDI. Patients with better posttreatment marital adjustment had significantly better outcomes at 6-month (r=.39, p<.01), 12-month (r=.51, p<.001), and 18-month follow-up (r=.43, p<.001) on the HRSD. Patients with better posttreatment marital adjustment had significantly better outcomes at 12 months on the BDI (r=.43, p<.001) but not at 6 or 18 months. |

| Kung and Elkin, 2000 (47) | 96 patients with major depressive disorder | IPT or CBT | BDI-I and HRSD-17 | MAS modified so scores based on clinical evaluation rather than self-report | Marital adjustment at intake was not a significant predictor of depressive symptoms at termination. Patients with higher marital adjustment at termination and higher marital improvement over the course of treatment showed lower depressive symptoms and improved social functioning at 6-months (Λ=.89, df=1, 71, p=.02), at 12-months (Λ=.66, df=1, 67, p<.001), and 18-month (Λ=.80, df=1, 70, p<.001) follow-up. |

| Bernecker et al., 2014 (32) | 95 patients with major depressive disorder | IPT | BDI-II, HRSD-17, GAF | DAS, IIP | Decrease in dyadic adjustment was related to lower posttreatment depression scores (β=2.028, p=.008, BDI-II self-rated; β=1.474, p=.022, HRSD-17 clinician-rated). At a trend-level (p<.10), decrease in interpersonal problems was associated with lower BDI-II score. |

| Constantino et al., 2013 (33) | 70 patients with primary diagnosis of major depressive disorder | IPT | Remission=criterion 1: BDI-II≤14.29 and change in BDI-II ≥8.46 pts from baseline; criterion 2: BDI-II ≤10 | DAS, IIP | Interpersonal problems and dyadic adjustment were not significantly associated with depression outcomes. |

| Interpersonal style | |||||

| Quilty et al., 2013 (48) | 125 patients with major depressive disorder | CBT or IPT | Change in BDI-II, change in HRSD-17 | IIP-32 | Pretreatment IIP-32 agency and amplitude were associated with decreased change in depression on the HAM-D (r=–.45, p<.01; r=–.29, p<.05) and on the BDI-II (r=–.44, p<.01; r=–.38, p<.01). |

| Altenstein-Yamanaka et al., 2017 (44) | 144 patients with major depressive disorder | CBT or exposure-based cognitive therapy for depression | BDI-II, IDC-S, SCL-9 | IIP, IMI rated by significant other | Changes in IMI dimensions were not associated with any of the pre-post changes in BDI-II, IDS-C or SCL-9 at termination. Increases in IMI agency were significantly associated with lower 3-month follow-up change in BDI-II (r=–.23; p=.03) and SCL-9 (r=–.23; p=.03), but not with change in IDS-C (r=–.14; p=.17). IMI communion, IIP agency, and IIP communion did not have a significant effect on symptom change at termination or follow-up. |

| Renner et al., 2012 (43) | 523 patients with recurrent major depressive disorder | Cognitive therapy | Change in HRSD-17 | IIP | Higher baseline IIP-C agency scores had lower symptom scores in the middle and end of cognitive therapy (F=1.56, df=18, 6,038.06, p=.06). |

| Marquett et al., 2013 (49) | 60 older adults with major depressive disorder, dysthymic disorder, or minor depressive disorder | CBT | Change in BDI-II | Locus of control | Patients self-reporting an external locus of control had a poorer response to treatment (β=2.11, p=.02). However, those who reported a tendency to assign blame for a stressful event to someone else were more likely to benefit from treatment (β=–1.94, p=.02). |

| Capacity to achieve intimacy | |||||

| Attachment security | |||||

| Saatsi et al., 2007 (52) | 110 patients with major depressive disorder | Cognitive therapy | BDI-I or BDI-II | IIP and attachment vignettes combined | Secure patients (adjusted M=9.51, SD=3.24) had significantly lower posttreatment depression scores than avoidant (adjusted M=17.46, SD=1.86, p=.05) and ambivalent (adjusted M=19.66, SD=3.24, p=.05) patients. The effect size for the association between attachment style and outcome was .80. Therapeutic alliance appeared to mediate the relationship between attachment style and outcome. |

| Reis and Grenyer, 2004 (53) | 58 patients with major depressive disorder | Supportive-expressive dynamic therapy | HRSD-17; remission=HRSD score ≤7 | RQ | Patients with a fearful attachment style demonstrated poorer overall treatment response (r=–.31, p<.05). Patients achieving remission reported significantly lower levels of fearful (t=–2.45, p=.02) and preoccupied attachment (t=–2.64, p=.01) at baseline than those who did not remit. Symptom remission was not predicted by dismissive avoidant attachment; however, a trend association in the expected direction between dismissive attachment and treatment response late in therapy was found (β=–.26, p=.08). |

| Constantino et al., 2013 (33) | 70 patients with primary diagnosis of major depressive disorder | IPT | Remission=criterion 1: BDI-II ≤14.29 and change in BDI-II ≥8.46 pts from baseline; criterion 2: BDI-II ≤10 | RSQ, ECR | Pretreatment score on fearful attachment (on RSQ only) was found to be the best predictor of depression remission (criterion 1: χ2=7.172, p<.01; criterion 2: χ2=7.792, p<.01). Patients with lower pretreatment fearful scores (<3.75) were more likely to remit (criterion 1: 81% [26/32]; criterion 2: 80% [16/20]) than patients with higher pretreatment scores (≥3.75) (criterion 1: 44% [8/18], criterion 2: 40% [12/30]). Other attachment styles were not predictive of outcome. |

| Cyranowski et al., 2002 (54) | 162 women with recurrent major depressive disorder | IPT | HRSD-17 <7 for 3 consecutive weeks during first 24 weeks of treatment | RQ | Attachment group categorization did not distinguish between patients who did or did not remit with IPT treatment; however, there was a positive association between high fearful avoidant attachment ratings and longer time to clinical stabilization among patients who achieved remission with IPT (r=.32, p<.01). High secure attachment ratings showed a trend toward shorter time to stabilization among patients achieving remission with IPT (r=–.19, p<0.08). |

| Bernecker et al., 2014 (32) | 95 patients with major depressive disorder | IPT | BDI-II, HRSD-17, GAF | ECR | At a trend-level (p<.10), decrease in attachment avoidance was associated with higher GAF. Changes in attachment anxiety were not significantly related to depression outcomes. |

| Barber and Muenz, 1996 (40) | 88 patients with major depressive disorder | Cognitive therapy and IPT | BDI-I, HRSD-17 | PAF | Patients who scored higher for avoidant personality disorder characteristics responded better to cognitive therapy than IPT on both the BDI-I and HRSD-17 (r=.33). |

| McBride et al., 2006 (55) | 56 patients with major depressive disorder | CBT and IPT | Change in BDI-II, change in HRSD | RSQ | Patients with high attachment avoidance responded better to CBT compared with IPT, even after the analysis was controlled for personality dysfunction. On the BDI-II, changes in depression were significant for CBT (β=–.44, p<.05) but not for IPT (β=.30, p>.05). Similarly, for the HAM-D, changes in depression in CBT were significant (β=–.55, p<.05) but not for IPT (β=.18, p>.05). |

| Bernecker et al., 2016 (56) | 69 patients with major depressive disorder | CBT and IPT | BDI-II (self-report); HAM-D-6 (clinician-rated) | RSQ, ECR-R | CBT and IPT were equally effective regardless of patients’ attachment styles. Across treatments, attachment avoidance was marginally associated with outcome, such that higher avoidance was associated with greater self-reported (ECR-R avoidance β=.27, p=.06) and clinician-rated (ECR-R avoidance β=.27, p=.06; RSQ avoidance β=.35, p=<.01) depression at termination. Attachment anxiety was associated with lower clinician-rated (ECR-R anxiety β=–.28, p=.04); RSQ anxiety (β=–.30, p=.02) but not self-reported depression at termination. |

| Reliance on others | |||||

| Byrd et al., 2010 (57) | 66 patients with mood, anxiety, and adjustment issues at a university graduate program training clinic | Psychotherapy from interpersonal, CBT, psychodynamic, eclectic orientations | Outcome Questionnaire-45 | AAS | Patients who were more comfortable with closeness (r=–0.37, p<.05) and comfortable depending on others (r=–0.37, p<0.05) showed greater gains in overall functioning at end of treatment. Rejection anxiety was not significantly related to outcome. |

| Marquett et al., 2013 (49) | 60 older adults with major depressive disorder, dysthymic disorder, or minor depressive disorder | CBT | BDI-II | Brief Cope | Patients self-reporting high use of emotional support in coping with stressful events were more likely to benefit from treatment (β=–1.95, p=.01). |

| Zlotnick et al., 1996 (58) | 188 patients with major depressive disorder | CBT and IPT | BDI-I | Life Events Inventory interpersonal stress items, Social Network Form | Greater social support (β=–1.88, p=0.0002), particularly the presence of close friends who act as confidants (β=–2.95, p=0.0001), was associated with lower depression scores at 6-month follow-up. |

| Moos and Cronkite, 1999 (29) | 313 patients with major depressive disorder | Unspecified | Remission=DSSI <1 SD above baseline mean of nondepressed control group and no hospitalization for depression | Responses on a 4-pt scale from "never" to "fairly often" to 1) "avoid being with people in general" and 2) "keep your feelings to yourself when coping with stressful situations” | Patients who at baseline reported greater social avoidance, particularly those who cope with stressors by avoiding, rather than seeking, social support, were at greater risk of a chronic course of depression following treatment. Specifically, among those who reported avoidance of people, 57.1% achieve partial or full remission compared with 75.0% who did not avoid people (p<.001). |

| Shahar et al., 2004 (59) | 144 patients with major depressive disorder | IPT or CBT | Latent variable consisting of BDI-II, SCL-90, HRSD-17, and GAS as indicators | DAS-A, Social Network Form | Patients with high levels of perfectionism, related to avoidance of intimacy and self-disclosure, had worse treatment outcomes (β=–.32, p<0.001). This relationship was mediated by the quality of the patient’s social network. Correlation between latent variables social network and symptoms posttreatment (r=–.52, p<0.01). |

| Hardy et al., 2001 (60) | 24 patients with major depressive disorder | Cognitive therapy | BDI-I | IIP, DAS-A | Patients with “underinvolved” (r=0.62, p<0.01) and “overinvolved” (r=0.51, p<0.01) interpersonal styles had higher depression scores at the end of treatment, after the analysis was controlled for pretreatment scores. Therapeutic alliance appeared to mediate the relationship between interpersonal style and outcome. |

| Quality of object relations | |||||

| Van et al., 2008 (63) | 81 patients with major depressive disorder | Short-term dynamic supportive therapy | HRSD-17 | DP | The overall maturity of object relations did not predict outcome; the only subscale of the object relationships measure to predict outcome was individuation, where patients with higher individuation scores (representing an experience of the other as equal, experience of self that is consistent, and appropriate relationships needs) showed better psychotherapy outcomes (β=0.26; p=0.02). |

| Zilcha-Mano et al., 2016 (64) | 149 depressive patients | Supportive expressive therapy (SET) or placebo (PBO) or medication | HRSD-17 | CRQ-R | Reduction in negative representation predicted subsequent reduction in depressive symptoms (β=1.97, t=2.15, df=70, p=.03). No significant main effect was found for positive relationship representations (p=.74). However, a significant interaction was found between positive relationship representations and treatment condition (F=3.19, df=2, 56, p=.04) such that greater improvement in positive relationship representations predicted greater symptom reduction in SET than in PBO (β=4.97, t=2.18, df=56, p=.02), but not in medication vs. PBO (β=0.33, t=1.71, df=56, p=.84). |

| Høglend and Piper, 1995 (66) | 107 patients with adjustment disorders, anxiety, and affective disorders across two independent studies | Brief psychodynamic therapy | Composite measures each with 2 factors: general symptoms/dysfunction and individualized problems (in one sample) or dynamic change (in another sample) | QORS | At 5-month follow-up, patients with high QOR showed a trend toward fewer symptoms and less general dysfunction after a treatment with greater focal adherence in one of two samples studied (r=.39, p<.10). Patients with low QOR had significantly more favorable outcome at follow-up after a treatment with less focal adherence in both samples studied (at 4 years r=–.40, p<.05 and at 5 months r=–.49, p<.05). |

| Piper et al., 1998 (67) | 144 patients with major depression (48.6%) and dysthymia (26.4%), anxiety disorder (7.6%), adjustment disorder (6.9%), and alcohol abuse (6.2%) | Interpretive and supportive forms of short-term psychodynamic therapy | BDI-I | QORS | Patients with high QOR had more favorable depression outcomes with interpretive therapy (r=–.26, p<.05). QOR was not significantly related to depression outcome in supportive therapy (r=.07, ns). |

| Piper et al., 2004 (62) | 171 patients; the most frequent disorders were current major depression (48.6%) and dysthymia (26.4%), followed by anxiety disorder (7.6%), adjustment disorder (6.9%), and alcohol abuse (6.2%) | Interpretive and supportive forms of short-term psychodynamic therapy | Composite measure with 3 factors: general symptomatology and dysfunction, social-sexual maladjustment, and nonuse of mature defenses and family dysfunction | QORS | For patients receiving interpretive therapy, a significant interaction effect for patient-rated pattern of alliance and QOR was found with general symptoms (effect size r was .26, p=.03). For patients with high QOR, greater increases in patient-rated alliance was associated with better outcome. For low QOR patients, greater decrease in patient-rated alliance was associated with better outcome. A main effect of QOR was found for each of the three outcome factors: general symptoms, r=.29, p=.02; social-sexual, r=.41, p=.001; and nonuse of mature defenses and family pathology, r=.24, p=.04. For patients receiving supportive therapy, QOR did not emerge as a moderator. |

| Høglend et al., 2006 (68) | 100 patients; the most frequent disorders were major depressive disorder single episode (28%), major depressive disorder recurrent (16%), dysthymia (14%) | Psychodynamic therapy separated into two groups with and without transference interpretations | Psychodynamic functioning scales, GAF | QORS | Patients with low QOR showed a trend toward better treatment outcomes on the psychodynamic functioning scales (Cohen’s d=.54, p=.08) and on the GAF (Cohen’s d=.55, p=.08) with treatment that included transference interpretations. Outcomes of patients with high QOR showed no difference across groups with or without transference interpretations. |

| Høglend et al., 2011 (65) | 100 patients with depression and anxiety | Psychodynamic therapy | Psychodynamic functioning scales | QORS | The association between working alliance and the effects of transference work varied significantly depending on level of QOR (β=–1.7, p=0.03). Patients with low QOR were more positively affected by transference interpretations in the context of a weak therapeutic alliance, whereas for patients with high QOR and high alliance, a negative effect of transference work was found. The effect size for this relationship was 0.49. |

| Lindfors et al., 2014 (34) | 326 patients with anxiety or mood disorders | Short-term solution-focused therapy, short-term psychodynamic therapy, or long-term psychodynamic therapy | SCL-90-GSI | QORS | Among those with high QORS, faster benefits appeared during the 7-month and 1-year follow-up in short-term therapy; however, at the 3-year follow-up, long-term psychodynamic therapy resulted in greatest improvement with a mean SCL-90-GSI score of .82 and a 32% reduction of symptoms in the short-term groups and SCL-90-GSI score of .64 and a 49% reduction of symptoms in the long-term group. No significant differences were found between therapy groups among those with low QORS at termination; however, nonsignificantly greater benefits were seen for those in long-term therapy at 2- and 3-year follow-up. |

| Category | Positive findings | Negative findings | Mixed findings | Null findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capacity to engage with others | ||||

| Access to social support (N=6) | Moos and Cronkite, 1999 (29); Coffman et al., 2007 (31)a; Bernecker et al., 2014 (32)b | Lindfors et al., 2014 (34) | Constantino et al., 2013 (33); Meyers et al., 2002 (30) | |

| Marital status (N=8) | Meyers et al., 2002 (30); Fournier et al., 2009 (35) | Menchetti et al., 2014 (39) | Barber and Muenz, 1996 (40); DeBolle et al., 2010 (41) | Jarrett et al., 2013 (36); Bastos et al., 2017 (37); Lemmens et al., 2016 (38) |

| Capacity to navigate relationships | ||||

| Interpersonal difficulty (N=10) | Meyers et al., 2002 (30); Connolly Gibbons et al., 2003 (42); Renner et al., 2012 (43); Jarrett et al., 2013 (36); Altenstein-Yamanaka et al., 2017 (44); Whisman et al., 2001 (46); Denton et al., 2010 (45); Kung and Elkin, 2000 (47) | Bernecker et al., 2014 (32) | Constantino et al., 2013 (33) | |

| Interpersonal style (N=4) | Quilty et al., 2013 (48); Altenstein-Yamanaka et al., 2017 (44); Renner et al., 2012 (43) | Marquett et al., 2013 (49) | ||

| Capacity to achieve intimacy | ||||

| Attachment security (N=8) | Saatsi et al., 2007 (52); Reis and Grenyer, 2004 (53); Constantino et al., 2013 (33); Bernecker et al., 2014 (32)b; Bernecker et al., 2016 (56) | Cyranowski et al., 2002 (54) | Barber and Muenz, 1996 (40); McBride et al., 2006 (55) | |

| Reliance on others (N=6) | Byrd et al., 2010 (57); Marquett et al., 2013 (49); Zlotnick et al., 1996 (58); Moos and Cronkite, 1999 (29); Shahar et al., 2004 (59); Hardy et al., 2001 (60) | |||

| Quality of object relations (N=8) | Van et al., 2008 (63); Zilcha-Mano et al., 2016 (64); Piper et al., 1998 (67); Lindfors et al., 2014 (34) | Høglend and Piper, 1995 (66); Piper et al., 2004 (62); Høglend et al., 2006 (68); Høglend et al., 2011 (65) | ||

Capacity to Engage With Others

Access to social support.

Marital status.

Capacity to Navigate Relationships

Interpersonal difficulty.

Interpersonal style.

Capacity to Achieve Intimacy

Attachment security.

Reliance on others.

Quality of object relatedness.

Discussion and Conclusions

References

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

History

Keywords

Authors

Competing Interests

Funding Information

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Citations

Export Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.

For more information or tips please see 'Downloading to a citation manager' in the Help menu.

View Options

View options

PDF/EPUB

View PDF/EPUBLogin options

Already a subscriber? Access your subscription through your login credentials or your institution for full access to this article.

Personal login Institutional Login Open Athens loginNot a subscriber?

PsychiatryOnline subscription options offer access to the DSM-5-TR® library, books, journals, CME, and patient resources. This all-in-one virtual library provides psychiatrists and mental health professionals with key resources for diagnosis, treatment, research, and professional development.

Need more help? PsychiatryOnline Customer Service may be reached by emailing [email protected] or by calling 800-368-5777 (in the U.S.) or 703-907-7322 (outside the U.S.).