The prevalence of adolescent obesity is estimated at 21% (

1). Several factors place all youths at risk for elevated body weight (

2); however, some groups may be particularly vulnerable to conditions associated with obesity, such as eating disorders (

3). One population susceptible to both obesity and eating disorders may be adolescent dependents of military personnel (

4–

6). Indeed, data suggest that such youths may face unique psychosocial stressors specific to their parents’ careers, such as parental deployment, multiple location changes, and new social environments (

7). These stressors may result in risk for disordered eating and excess weight gain. In contrast to rates for civilian adults (

8), a high rate of disordered eating and associated distress has been reported among female and male service members (

9). These behaviors and feelings may be transmitted to service members’ adolescent children (

10). Additionally, exposure to parents’ focus on fitness standards may promote disordered eating among the children of service members (

10).

The interpersonal model (

11) provides an explanation for how obesity and disordered eating may manifest in youths. Extrapolating from interpersonal theory for depression (

12), it is postulated that difficult relationships lead to depressive symptoms and thereby promote emotionally induced eating. Emotional eating, which is correlated with and predictive of disordered eating (

13), may serve as a maladaptive coping strategy that results in excess weight gain (

11). The interpersonal model has been widely used to examine binge eating among adults (

14) and has been validated with civilian youths (

15,

16). Prior studies, however, have not focused on specific domains of psychosocial functioning. Although adolescence is typically considered a developmental stage during which peer connections are crucial (

17), research has also emphasized the importance of parental relationships (

18). Given the unique interpersonal stressors faced by adolescent military dependents, interpersonal theory may be relevant to our understanding of disordered eating and obesity in this population (

5,

19). Moreover, elucidating social functioning across differing domains and relationships, including loneliness; social adjustment with family and friends; and attachment to peers, mothers, and fathers, may further refine the potential mechanisms of interpersonal theory for such youths. These specific aspects of social functioning may be particularly important to assess because previous research has linked peer and parental relationships and attachment to emotional eating (

20,

21).

Therefore, in this study, we cross-sectionally tested the utility of the interpersonal model among adolescent military dependents at high risk for excess weight gain and binge eating disorder. Adolescents were assessed prior to participation in a prevention program aimed to reduce both conditions. We hypothesized that depressive symptoms would mediate the association between multiple domains of social functioning and emotional eating.

Methods

Participants and Recruitment

Adolescent military dependents were recruited for a study aimed at preventing adult obesity and binge eating disorder (

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02671292). All participants were at high risk for both conditions, as indicated by reports of loss-of-control eating and/or anxiety symptoms (

22–

26). Recruitment efforts were targeted toward parents of military-dependent youths ages 12–17 and included posting flyers in military communities, in-person information booths located at local uniformed services hospital clinics, referrals from clinicians, and direct mailings to parents of children covered by or eligible for military health insurance (Tricare). Inclusion criteria required a ≥85th percentile body mass index (BMI, kg/m

2) and self-report of either ≥1 episode of loss-of-control eating in the past 3 months or a trait anxiety score ≥32 (

27) on the Spielberger State–Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children—A Trait Scale (STAIC) (

28). Exclusion criteria included major medical or psychiatric conditions other than binge eating disorder, involvement in a structured weight-loss program or psychotherapy, medications known to affect appetite or body weight, or loss of >3% of body weight in the past 3 months. Youths who were taking a stable dosage of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor or stimulant medication were included if their weight had been stable for the 3 months prior to assessment. Girls taking oral contraceptives were eligible if their weight had been stable for ≥2 months while they used the medication, and girls were excluded if they were currently or recently pregnant or breastfeeding. The study was approved by the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USUHS) and the Fort Belvoir Community Hospital (FBCH) institutional review boards.

Procedures and Measures

Following screening via telephone interview, potentially eligible individuals attended a baseline visit (July 2015 through February 2019) at either USUHS or the FBCH Family Medicine Clinic. Parents and adolescents provided written consent and assent, respectively. Height and fasting weight were measured with calibrated instruments, and body mass index adjusted for age and sex (BMI

z) was calculated (

29). Participants completed self-report measures of social functioning, depressive symptoms, emotional eating, and anxiety, and were interviewed to assess for the presence of loss-of-control eating. Participants were assessed prior to initiation of any intervention. Adolescents were compensated for their participation with a $50 gift card.

General loneliness was assessed with the Loneliness and Social Dissatisfaction Scale (

30), a reliable and valid questionnaire for use among youths (

16,

31). This measure consists of 16 scored items and eight filler items. A total score was generated, with higher scores indicating greater loneliness. This questionnaire demonstrated excellent reliability in the current sample (Cronbach’s α=0.90).

Social adjustment was assessed with the Social Adjustment Scale–Self-Report (

32), a questionnaire that evaluates social adjustment during the past 2 weeks. Three subscale scores, related to school, family, and friends, are generated and averaged for a total score. The Social Adjustment Scale has shown satisfactory reliability and validity in a wide variety of samples (

33). Higher scores indicate more social problems. Because the school subscale focuses on academics and has been shown to be less relevant for the interpersonal model (

16), it was not included as an independent variable. This measure demonstrated satisfactory reliability in the current sample for the total score (Cronbach’s α=0.78) and for the family (α=0.72) and friends (α=0.64) subscales.

Parent and peer attachment were assessed with a revised version of the Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (

34). Whereas the original version contains two measures, one for parental attachment and one for peer attachment, the revised version is composed of three separate scores, evaluating attachment to mother, father, and peers (Armsden and Greenberg, 1989). The revised version is reliable for use with adolescents (

35); higher scores indicate greater attachment. This measure demonstrated very good reliability in the current sample for the scores for mother (Cronbach’s α=0.95), father (α=0.96), and peers (α=0.92).

We assessed depressive symptoms by using the Beck Depression Inventory–II (

36). This measure has demonstrated good reliability and validity for use among adolescents (

37) and consists of 21 questions; higher scores correspond to greater symptoms of depression, and a score ≥25 is considered clinically elevated (

27,

36). The questionnaire demonstrated good reliability in the current sample (Cronbach’s α=0.85).

Emotional eating was assessed with the Emotional Eating Scale for Children (

38), which was based on the original Emotional Eating Scale (

39). This measure, which has demonstrated good psychometric properties (

38) and construct validity (

40), consists of 25 items, whereby participants are asked to determine their desire to eat in response to negative emotions. Higher scores represent greater emotional eating. The total score for emotional eating demonstrated very good reliability in the current sample (Cronbach’s α=0.95).

We determined loss-of-control eating during the past 3 months through the Eating Disorder Examination Interview, version 14 (

41). This interview has demonstrated excellent internal consistency for use with treatment-seeking adolescents with overweight (

42), as well as very good reliability and validity among children and adolescents prone to obesity (

43,

44). None of our participants met criteria for binge eating disorder.

We measured anxiety with the STAIC (

28), a reliable and valid measure for use among adolescents (

45). This measure includes 20 items; higher scores indicate greater anxiety. Although there are no clinical cutoff scores for the measure, on the basis of our prior research (

27), we chose a score of 32 or greater as an indicator of elevated symptoms. The STAIC demonstrated good reliability in the current sample (Cronbach’s α=0.77).

Data Analysis

We completed all analyses with SPSS Statistics, version 25. We screened the data for outliers and normality. To minimize outliers’ influence on analytic findings, we recoded extreme outliers (defined as more than three standard deviations from the mean, N=15) to three standard deviations from the mean (

46). Unless published guidelines were available for dealing with missing data, we scored questionnaires if at least 80% of the data from each measure or subscale was present, and for each score, we imputed missing data by using the within-subject mean of the nonmissing items. For each questionnaire, less than 1% of items was missing, a rate that would be unlikely to affect findings or differ from other methods of imputation (

47). We examined participant characteristics by groups (reports of loss-of-control eating only, anxiety only, both loss-of-control eating and anxiety) via chi-square tests or one-way analyses of variance (ANOVA), as appropriate. For significant ANOVAs, we used post-hoc Tukey tests to determine differences across groups. For the primary analyses, we conducted seven cross-sectional mediation models with the Preacher and Hayes Indirect Mediation macro for SPSS (

48) to examine the independent roles of multiple social constructs within the interpersonal model. The independent variables in each respective model were loneliness; social adjustment for family, friends, and total scores; and attachment to mother, father, and peers. For each model, we used depressive symptoms as the mediator and emotional eating as the dependent variable. For all mediation models, bootstrapping with 10,000 resamples was used to estimate the 95% bias-corrected confidence interval (CI) for indirect effects. We adjusted all mediation models for age, sex, race, and BMI

z, along with presence or absence of loss-of-control eating during the past 3 months and elevated trait anxiety, because these two variables were inclusion criteria. We used listwise deletion for missing data in each model. We considered differences significant at p<0.05.

Results

A total of 136 participants (56% girls, 44% boys; BMI

z=1.93±0.38) were included. The racial-ethnic distribution of the sample was 43% non-Hispanic white; 21% Hispanic or Latino; 20% non-Hispanic black; 8% multiple races or other race; 6% unknown; and 3% non-Hispanic Asian. Among participants, 84% (N=114) had a father and/or stepfather in the military, and 32% (N=44) had a mother and/or stepmother in the military. Six percent (N=8) of participants reported loss-of-control eating only, 41% (N=56) reported only elevated anxiety, and the remaining 53% (N=72) of youths reported both loss-of-control eating and elevated anxiety symptoms.

Table 1 presents data for the overall sample, as well as by participants who reported loss-of-control eating and/or elevated anxiety. The three groups did not differ by age, BMI

z, social adjustment with family or friends, attachment to peers, depressive symptoms, race-ethnicity, or sex (p>0.05). There were main effects for group differences in loneliness, total social adjustment, attachment to mother, attachment to father, and emotional eating (p<0.05). Post-hoc comparisons that remained significant across groups are shown in

Table 1. In general, the results showed more loneliness, poorer social adjustment, less attachment to parents, and more emotional eating among participants with both loss-of-control eating and high anxiety.

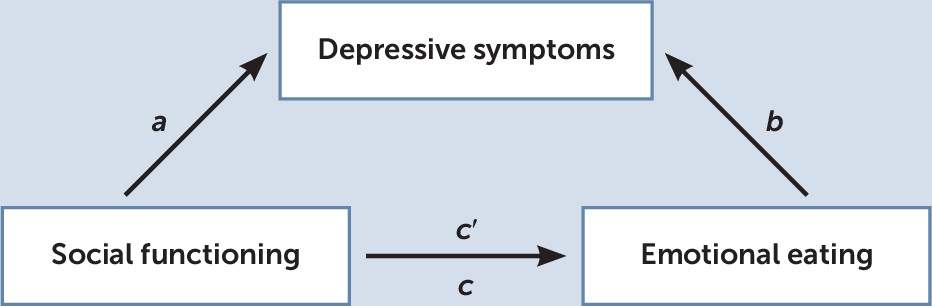

Figure 1 is a theoretical mediation model that portrays the independent roles of multiple social constructs within the interpersonal model. Path a represents the relationship between social functioning and depressive symptoms, path b represents the relationship between depressive symptoms and emotional eating, and a×b represents the impact of social functioning on emotional eating through depressive symptoms. Path c is the total association between social functioning and emotional eating, and path c′ is the association between social functioning and emotional eating, after adjusting for depressive symptoms.

Loneliness and Social Dissatisfaction Scale

Depressive symptoms significantly mediated the relationship between loneliness and emotional eating (R2=0.14; ab=0.01, 95% CI=<0.01–0.02). Higher loneliness scores were significantly associated with greater depressive symptoms (a=0.31, standard error [SE]=0.09, p<0.01), and greater depressive symptoms were significantly associated with increased emotional eating (b=0.03, SE=0.01, p=0.01). The direct effect of loneliness on emotional eating (c=0.01, SE=0.01, p=0.14) decreased with the addition of depressive symptoms (c′=0.01, SE=0.01, p=0.53).

Social Adjustment Scale

Depressive symptoms did not significantly mediate the relationship between total score on social adjustment and emotional eating (R2=0.14; 95% CI=–0.14 to 0.32). In contrast, depressive symptoms significantly mediated the relationship between the social adjustment–family subscale score and emotional eating (R2=0.18; ab=0.09, 95% CI=<0.01–0.19). The family subscale score was significantly and positively associated with depressive symptoms (a=4.51, SE=0.97, p<0.01); however, depressive symptoms were not significantly associated with emotional eating (b=0.02, SE=0.01, p=0.053). The significant effect of the social adjustment–family score on emotional eating (c=0.34, SE=0.11, p<0.01) was attenuated with the addition of depressive symptoms (c′=0.26, SE=0.12, p=0.03).

Depressive symptoms also significantly mediated the relationship between the social adjustment–friends subscale scores and emotional eating (R2=0.14; ab=0.15, 95% CI=0.05–0.29). The friends subscale score was significantly and positively associated with depressive symptoms (a=5.39, SE=1.02, p<0.01), and depressive symptoms were significantly and positively associated with emotional eating (b=0.03, SE=0.01, p=0.01). The direct effect of the social adjustment–friends subscale score on emotional eating (c=0.14, SE=0.12, p=0.25) was attenuated with the addition of depressive symptoms (c′=–0.01, SE=0.13, p=0.94).

Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment

Depressive symptoms did not significantly mediate the relationship between attachment to mother and emotional eating (R2=0.19; 95% CI=–0.004 to 0.001). In contrast, depressive symptoms significantly mediated the relationship between scores on attachment to father and emotional eating (R2=0.23; ab=–0.003, 95% CI=–0.01 to –0.001). Poorer attachment to father was significantly associated with greater depressive symptoms (a=–0.09, SE=0.03, p=0.01), and greater depressive symptoms were significantly associated with more emotional eating (b=0.04, SE=0.01, p<0.01). The direct effect of attachment to father on emotional eating (c<0.01, SE<0.01, p=0.33) increased with the addition of depressive symptoms (c′=0.01, SE<0.01, p=0.06).

Depressive symptoms also significantly mediated the relationship between attachment to peers and emotional eating (R2=0.19; ab=–0.004, 95% CI=–0.01 to –0.001). Worse attachment to peers was significantly associated with greater depressive symptoms (a=–0.12, SE=0.05, p=0.01), and greater depressive symptoms were significantly associated with more emotional eating (b=0.03, SE=0.01, p<0.01). The direct effect of attachment to peers on emotional eating (c=–0.002, SE=0.01, p=0.64) decreased with the addition of depressive symptoms (c′< 0.01, SE=0.01, p=0.78).

Discussion

The interpersonal model may be particularly relevant to our understanding of adolescent military dependents at risk for excess weight gain and binge eating disorder. Depressive symptoms were found to significantly mediate the relationships between multiple domains of social functioning (i.e., loneliness, social adjustment related to family and friends, and attachment to father and peers) and emotional eating. Depressive symptoms did not significantly mediate the relationship between total social adjustment and emotional eating, possibly because of the inclusion of the school subscale, which emphasizes academic performance over social functioning, in the total score (

32). Whereas prior research has supported the relevance of the interpersonal model for civilian youths (

15,

16), the current study supports the salience of interpersonal theory for adolescent military dependents. Our findings expand on interpersonal theory to identify which kinds of psychosocial functioning may be most relevant to disordered eating among adolescent military dependents with overweight or obesity.

It is not surprising that the interpersonal model showed that peer relations may be related to disordered eating among adolescents. Data have consistently supported the importance of peer relationships and social connectivity among adolescents (e.g.,

17). For military dependents, such relationships may hold additional meaning because the mobility of the military family results in frequent relocations that require regularly developing new friendships and peer groups (

49). Given that difficult peer relations may relate to risk for excess weight gain and disordered eating among civilian youths (

50), social functioning related to one’s peers may have an especially significant role within the interpersonal model for adolescent military dependents.

Depressive symptoms also significantly mediated the relationship between social adjustment–family and emotional eating. Having a parent in the military can be associated with increased psychosocial stressors (

7), such as parental deployment and changing caregivers, both of which may explain the significance of this relationship within the interpersonal model. When we examined family social functioning more specifically, we found that depressive symptoms significantly mediated the relationship between attachment to fathers, but not to mothers, and emotional eating. Research with civilian samples has suggested that poorer maternal attachment is related to greater disordered eating and risk for weight gain, but the data have been mixed regarding the relationships among paternal attachment, disordered eating, and weight status (e.g.,

51). Of the current sample, 84% had a father in the military, and only 32% had a mother in the military. Exposure to a military parent’s focus on fitness standards (

9) may have a unique influence within the interpersonal model and risk trajectory for adolescent military dependents’ susceptibility to emotional eating, excess weight gain, and disordered eating. Additionally, fathers may be deployed more often than mothers, which could increase the importance of paternal relationships for youths because of safety concerns. Prospective data are needed to explore this possibility.

If supported prospectively, further study findings could be used to tailor interpersonal psychotherapy interventions for adolescent military dependents. Until such time, clinicians treating eating and weight concerns in this population may consider focusing therapy on mitigating the challenges of peer and parental relationships with the goal of reducing negative moods and subsequent overeating. This study’s strengths included the analysis of a hard-to-reach group of racially and ethnically diverse boys and girls that is typically neglected in research. The use of validated questionnaires to assess social functioning, depressive symptoms, emotional eating, and anxiety; a structured clinical interview to assess loss-of-control eating; and objective measurement of height and weight were also strengths.

A significant limitation of this study was its use of cross-sectional mediation models. Whereas the models prespecified the direction for causal relationships, the cross-sectional nature of the data did not allow for analysis of temporal relationships. Future research should examine these relationships prospectively. Additional limitations included the use of self-report measures to capture social functioning, depressive symptoms, emotional eating, and anxiety, and the potential lack of generalizability of the findings to non-military-dependent adolescents. Future studies should consider using experimental paradigms, such as interpersonal stressors and test meals in the laboratory, to determine whether the current findings would be replicated among both civilian and military adolescents.

Conclusions

The interpersonal model may be important in understanding the development of excess weight gain and disordered eating among adolescent military dependents. Longitudinal data are required to determine the impact of peer and family relationships, particularly relationships with fathers, on response to interventions based on interpersonal theory, as well as overall weight and disordered eating outcomes among adolescent military dependents.