Rational emotive behavior therapy (

3,

4), currently called rational emotive and cognitive-behavioral therapy (REBT), uses the original foundational approach of CBT. REBT is organized around the concept of rational and irrational beliefs (

3,

4) and, in keeping with the CBT framework described above (

1,

2), states that one’s emotional and/or behavioral reactions to certain activating life and/or personal events are largely mediated by the beliefs that one holds about these events. According to Ellis (

4), there are two types of beliefs—irrational and rational—and four irrational or rational categories: demandingness versus flexible and motivational preferences, awfulizing or catastrophizing versus nuanced evaluation of badness, frustration intolerance versus frustration tolerance, and global evaluation (of self, human worth, others, and life) versus unconditional acceptance (of self, others, and life) (

1,

5). Demandingness represents a primary irrational process, but not one that is proximal to emotional reactions. Indeed, demandingness leads to the secondary irrational beliefs (i.e., awfulizing and catastrophizing, frustration intolerance, and global evaluation), which are more proximal causes of dysfunctional emotions and psychopathology (

1).

REBT theory distinguishes between functional and dysfunctional emotions on the basis of the association made by individuals between events and cognitions and whether the behavioral consequences of these feelings are adaptive (

4). Negative emotions that follow irrational beliefs about negative events are called dysfunctional negative emotions, whereas emotions that follow rational beliefs about negative events are called functional negative emotions (

2).

Both REBT and CBT assume that individuals can change their unhealthy beliefs to healthy ones, which implies that individuals have the choice of showing functional or dysfunctional feelings and behaviors (

6). In more recent work, the REBT approach, compared with most other CBT methods, has been described as using different ways to help clients reach three major acceptances: unconditional acceptance of self, others, and life (

6). In studies of the two approaches, CBT has been tested more with specific-disorder protocols, whereas REBT has been used more with a transdiagnostic approach.

From Efficacy to Effectiveness Studies

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are the gold standard in testing the efficacy of any psychological treatment (i.e., the treatment works in controlled conditions and maximizes internal validity). To date, CBT (REBT alone or considered as a part of CBT) has been among the psychological interventions empirically investigated most frequently and has received the most empirical support (

7,

8). The efficacy of CBT has been evaluated in several meta-analyses (

9–

13), with positive results. More recently, the evidence supporting CBT has been strengthened by several rigorous clinical trials (

14,

15) and meta-analyses (

16–

18).

However, questions remain concerning the procedures used for increasing internal validity in RCTs—procedures that may compromise the external validity of the results. Specifically, these questions pertain to generalizability across patients, clinicians, and treatments used and about whether these characteristics of clinical trials are representative of clinical practice. Moreover, some studies (

19,

20) have found that up to 70% of patients who could benefit from depression treatment would not have been eligible to participate in a RCT efficacy study. The most common reasons for excluding patients from RCTs have been that they received subclinical diagnoses, had comorbid psychiatric diagnoses, or received adjunct treatments, such as medication. Because of these exclusionary problems and because efficacy studies fail to provide information about the transportability of interventions to more ecologically valid conditions, psychotherapy research requires an emphasis on effectiveness trials that evaluate interventions implemented under naturalistic conditions (

21,

22).

Effectiveness research investigates whether interventions that were tested in RCTs attain similar benefits in naturalistic settings; such research can include pretest-posttest, quasi-experimental, or experimental designs. According to Stewart and Chambless (

23), a study design can be categorized as having external validity when it achieves at least one of the following characteristics: it captures data in clinically representative settings (e.g., outpatient clinics, mental health centers), uses clinically representative therapists (e.g., practicing clinicians who do this job daily), or studies clinically representative patients (e.g., has few exclusion criteria). Additionally, the transdiagnostic approach to the treatment of clinical problems reflects the current at-hand orientation in real practice, as opposed to the model of selected interventions for specific disorders that characterizes randomized trials.

Several reviews have synthesized the results of CBT effectiveness studies. Stewart and Chambless (

23) conducted a meta-analysis of 56 CBT effectiveness studies for adult anxiety disorders to investigate whether CBT tested under well-controlled conditions can be generalized to less controlled settings. The effect sizes from pretest to posttest for disorder-specific symptom measures were large, suggesting that CBT for adult anxiety disorders is effective in clinically representative conditions. The findings demonstrated that results from effectiveness studies are similar to those obtained in efficacy trials. Hans and Hiller (

24) conducted a meta-analysis of 34 CBT effectiveness studies of outpatients receiving individual and group therapy for unipolar depressive disorder. Results showed large posttreatment effect sizes for reducing depression severity with outpatient CBT and moderate-to-large effect sizes for secondary outcomes. In a study of general psychological distress, Twomey et al. (

25) demonstrated the effectiveness of a computerized CBT program (MoodGYM, d=0.48) in reducing psychological distress among a sample of 149 public mental health service users. Hickie et al. (

26) found effect sizes in the same range (d=0.4) when measuring the level of psychological distress from pre- to posttest. Although the results were consistent with previous findings showing that individual and group outpatient CBT can be effectively transported to clinical practice, the study also found that patients encountered in clinical practice showed less improvement in depressive symptoms than did participants in RCTs.

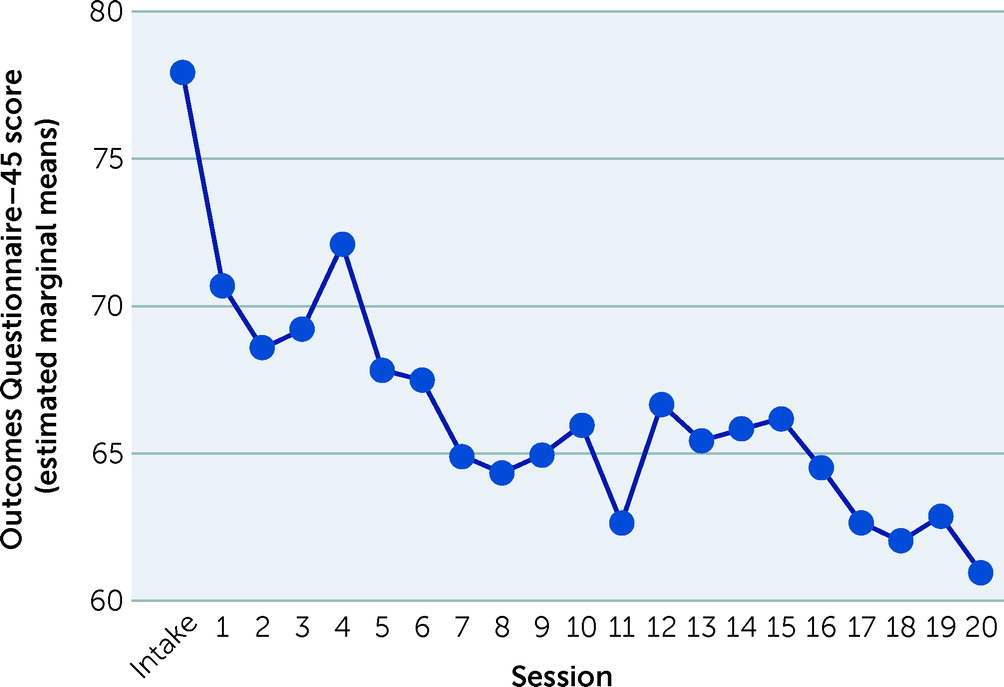

A commonly used method in ecological studies of psychotherapy, especially with center-based samples, is to track symptom change during therapy. The Outcome Questionnaire–45 (OQ-45) (

27) has become one of the 10 instruments most frequently used by practitioners to measure clinical outcomes (

28). Research using this type of measure has helped researchers identify whether patients receiving high doses of therapy would be no more likely to experience a clinically significant change than those who receive low doses (

29–

30). Baldwin et al. (

31) evaluated the dose-effect relationship and model of change by examining the relationship between the rate of change and total dosage of sessions among 4,676 patients who received individual psychotherapy. They showed that 1,242 patients achieved clinically significant change (measured with the OQ-45) and that faster rates of change were registered by the patients receiving small doses of treatment, whereas slower rates of change were linked to receiving larger doses of treatment.

Other important variables that can be investigated in such naturalistic studies of psychotherapy effectiveness are dropout rates and course of patients’ treatment response. High dropout rates (24%–66%) have been reported by studies (

32,

33) conducted in mental health centers. Low motivation for change was identified as a primary reason for dropout (

34). Studies addressing the long-term outcomes of psychotherapy found that early responders (e.g., patients improving within the first three sessions) had better outcomes at therapy termination and maintained their therapy gains (

35). Moreover, an early positive response to psychotherapy has been found (

36) to be a powerful predictor of outcomes among various samples. Also, some studies (

37–

39) have documented the effectiveness of brief time-limited therapy (eight to 16 sessions or five sessions of CBT) (

30,

37). It has been suggested that about 50% of treated patients in routine care might recover if they received about 18 to 21 sessions of psychotherapy (

40), although about 50% of clients will show reliable improvement after only seven sessions. However, it is also known that deterioration rates for patients in routine practice settings can be as high as 14% (

41), whereas the response rate (recovered and improved patients) for patients with clinical symptoms participating in 20 sessions of therapy is around 40% (

31).

Study Overview

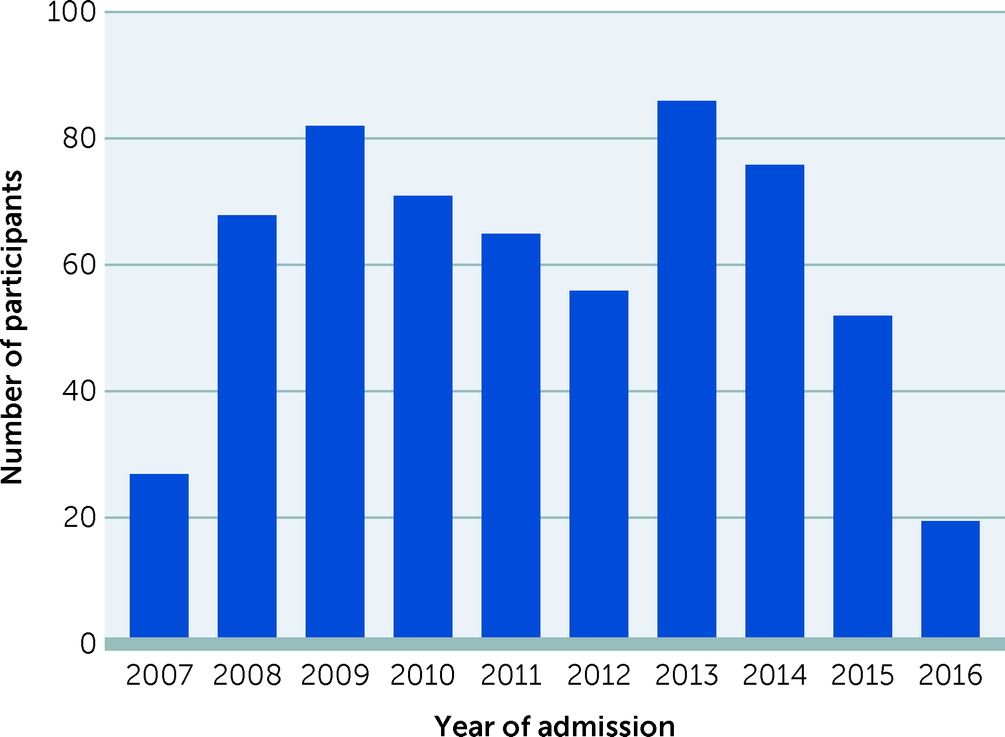

To our knowledge, systematic studies to date have not yet investigated the effectiveness of REBT. This research gap is surprising, because REBT has been practiced as the original form of CBT, and, from the beginning, the REBT literature has more closely resembled an effectiveness framework than an efficacy framework. Indeed, the Albert Ellis Institute (AEI) has for many decades offered services to the community that are based on the REBT model, focus on clinical problems as they appear in real life, are provided by therapists whose main job is conducting therapy, and implement both the transdiagnostic and categorical diagnostic approaches. Thus, the AEI seemed to be the perfect setting to evaluate the effectiveness of REBT with the purpose of understanding the impact of CBT more generally. Therefore, in this study, our main hypothesis was that the use of REBT can improve psychological functioning, expressed as lower symptom severity, of a sample of outpatients in naturalistic conditions.