Treatment Approach

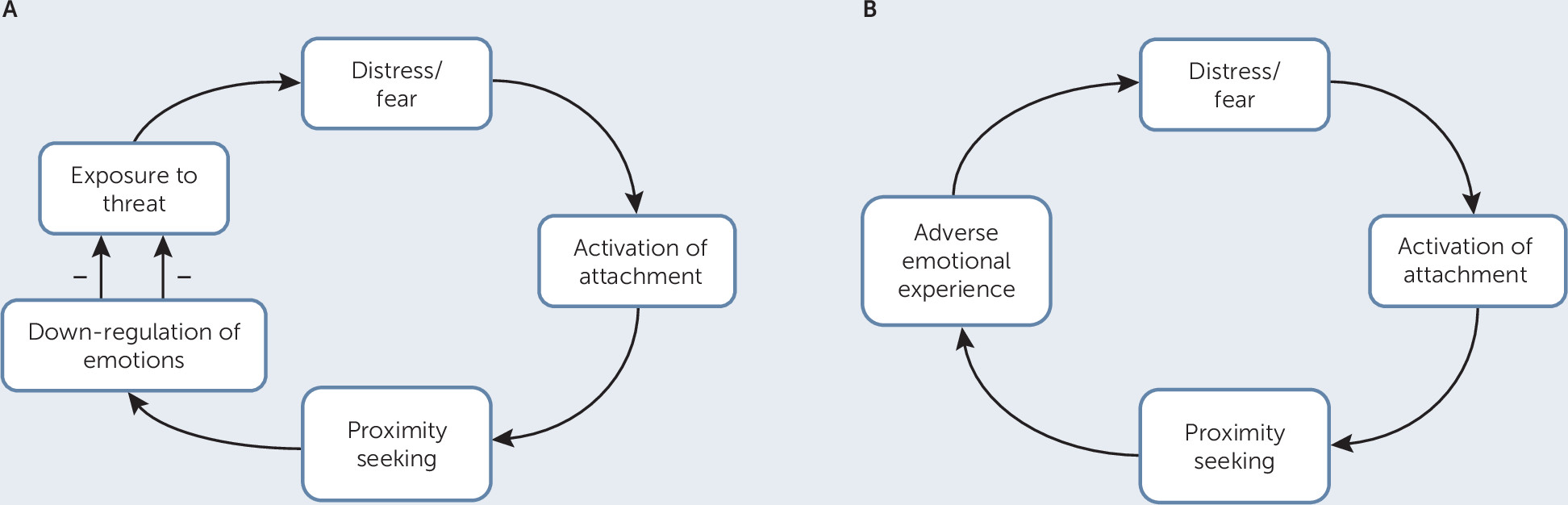

Dynamic interpersonal therapy for FSD (DIT-FSD) is an integrative PDT that focuses on the three core features of patients with FSD discussed above: the activation or reactivation of secondary attachment strategies to deal with persistent somatic problems, the resulting impairments in embodied mentalizing, and problems with epistemic trust (

9,

24).

Because patients with FSDs are notably heterogeneous with respect to the nature and origins of their problems, the ability to tailor treatment to patients’ needs and capacities is a central feature of DIT-FSD. For patients with more severe impairments in embodied mentalizing, therapy typically focuses on reactivating the capacity for embodied mentalizing before any work focusing on the content of the patient’s interpersonal dynamics can be done successfully. In DIT-FSD, this latter focus is based on the therapist and patient jointly formulating an interpersonal affective focus (IPAF)—a description of a recurring and often unconscious pattern of relating to the self and others that is linked to the onset and perpetuation of functional somatic problems.

DIT-FSD is offered in a 16-session format or, for patients with more severe symptoms, in a 26-session format. The time-limited nature of the treatment provides patients with a holding environment and activates the patient’s IPAF (e.g., “Why do I need such a long treatment? I have always been able to take care of things on my own,” or “Sixteen sessions will be way too short, I need many more”). Of course, at the end of DIT-FSD, some patients may benefit from longer treatment, but the aim of DIT-FSD is to empower the patient to continue his or her own treatment process as needed.

In what follows, we describe the 16-session format based on a brief summary of the treatment of Linda, a woman with severe and chronic gastrointestinal problems (all case material has been disguised to protect patient confidentiality).

The first phase of DIT-FSD (sessions 1–4) focuses on engaging the patient in treatment and jointly formulating an IPAF, however preliminary, as the focus of the treatment. Linda was referred to me (P.L.) after having suffered for years from severe and almost constant gastrointestinal problems. She had been diagnosed as having irritable bowel syndrome and chronic widespread pain, and she had undergone numerous medical tests and examinations in the past. Each time, she was told that her condition must largely be stress-related and that she needed to see a psychologist or psychiatrist.

During her intake interview, Linda told me that she had seen several psychologists, but none of them seemed to have understood her; they all seemed to agree with the view that her symptoms and complaints were largely psychological. Each time, after a few sessions, she terminated treatment. In DIT, this narrative is seen as a cautionary tale: the patient warns the therapist of not only what might reoccur in the therapeutic relationship (“people, including you as a therapist, do not understand me”) but also of what might happen if the therapist is yet another person who does not understand her (she will end the treatment). Because this template or pattern might also prove to be a central component of Linda’s IPAF, my initial response was to validate and normalize her adaptation strategy, expressing my surprise that both physicians and psychologists had not taken her seriously and saying that it must have been terrible given that she clearly was in pain and feeling desperate. In response, she started to cry. She then looked up and asked me whether I believed her. I told her that she did not need to convince me of the reality of her symptoms or of her feelings of desperation and depression because no one seemed to be able to help or even to understand her.

Hence, my empathic validation of her feelings of invalidation and recognition of the reality of her suffering led to a relaxation of her epistemic vigilance and the emergence of an interest in what else I thought about her and her problems. Together, we were then able to discuss whether she had experienced the feeling of not being understood before. This exchange led to an attachment memory: as a child, Linda always had the feeling that she was “second best” and that her parents, particularly her mother, preferred her sister. Throughout her childhood and adolescence, she had always attempted to be her “mother’s darling,” but she always seemed to fail to surpass her sister in this regard. She became desperate for her mother’s attention and felt very anxious whenever her mother seemed to disapprove of something that Linda did or wanted. When she was 10 or 11, Linda began to develop gastrointestinal symptoms. When I asked how she felt as a child and as a teenager, Linda responded that she felt constantly anxious and on guard. When I asked whether these feelings also may have taken a toll on her body (i.e., an embodied mentalizing focus), she responded that this was true: she always felt tense, as if there was a weight on her shoulders and a constant pressure in her stomach. I asked whether she now felt the same tension and pressure during the session. Linda responded that she had never thought of the connection between her anxious preoccupation with her mother and her gastrointestinal symptoms, but that in the here-and-now of the session, she felt that there must be a link between the two.

In DIT-FSD, we do not force a specific illness theory on the patient, but use interventions aimed at fostering embodied mentalizing so that the patient begins to experience possible links between a repetitive interpersonal pattern and somatic symptoms through “microslicing” of interpersonal events (i.e., exploring undifferentiated mental states in relation to interpersonal events in a step-by-step manner to break them down into specific mental states that are meaningfully linked to each other). This experience led Linda to talk about other relationships in which this anxious pattern of wanting to be the one who is preferred over others had recurred (with a teacher, with a man who gave her lessons at a pony club, and with two boyfriends she had dated before meeting her current partner). In her current relationship, she said that this pattern seemed to be somewhat less important because her partner was “extremely patient with her” (which could also be read as a cautionary tale).

In session 3, we were able to jointly arrive at a preliminary formulation of her IPAF. She saw herself as someone who was always there for others, caring for and helping them. However, she experienced others as being uncaring and as preferring other people, despite doing her utmost to please them. This experience made her feel sad, lonely, and despondent, but also highly anxious because it meant, in her experience, that no one really cared for her and that she was “all alone in the world” (an example of psychic equivalence functioning). Importantly, we were able to consider this pattern as an understandable adaptation strategy given the context in which she grew up. However, this strategy also had a large emotional and somatic cost: not only did she feel anxious and alone, she always felt tense and on guard, and she always felt as if there was “something on her stomach,” giving her cramps.

When we focused on her cramps and the feeling that there seemingly was always “something on her stomach,” she could, at first very cautiously and with a lot of shame, acknowledge that she also often felt frustrated and angry because others neglected her and did not understand her. She recalled, for instance, how one day when her sister had organized a barbecue for the whole family, Linda had felt so tense, frustrated, and angry that she had to leave early because she felt nauseated and had to vomit. She had left the barbecue without telling anyone and without mentioning that she felt unwell. Hence, her feelings of anger and frustration typically gave rise to high levels of bodily arousal and tension, which contributed to her gastrointestinal problems. Feelings of guilt inhibited her anger until the whole cycle started again. Linda, however, had always attributed her cramps to a somatic cause (an example of teleological functioning).

The second phase of DIT (sessions 5–12) involves a constant focus on how the IPAF recurs in the patient’s life. In addition, once the therapy has strengthened the patient’s capacity to reflect on the negative impact of this repetitive pattern of thinking and feeling and its link with presenting symptoms, the therapist and patient can jointly begin to consider alternative ways of relating to the self and others. This process is typically accompanied by an alleviation of the patient’s symptoms.

Although Linda initially remained somewhat reluctant to talk about her family and current relationships, she increasingly began to acknowledge—first during the sessions and then, as the treatment progressed, in the wider world—how her feelings of not being seen or understood weighed on her both symbolically and literally. In other words, she acknowledged how she had always felt oppressed and suppressed and how these feelings had led to a constant state of anxious tension. The emotional and physical costs of her expectation that others would not be there for her and that they preferred others above her became increasingly clear. At this point in the therapy, both her general feeling of being tense and her more specific gastrointestinal problems began to improve markedly. Not only did she feel less of a need to be “preferred” by others, she reported feeling more relaxed in the company of others. In addition, her almost endless worrying that others did not like her because of something she said or did not say, or did or did not do (which led to anxious thoughts about rejection and abandonment that often preoccupied her for days, an example of pretend mode functioning) considerably decreased. The fact that her partner continued to be supportive and reassuring played an important role in this context. She also began to distance herself more from her mother and sister and from friends whom she felt exploited her tendency to care for others and always be there for them. In the middle phase of treatment, DIT uses the full spectrum of interventions typically used in PDT. This spectrum includes supportive interventions when needed, interventions that foster embodied mentalizing, insight-oriented interventions (i.e., clarification, challenge, and interpretation), and directive interventions to encourage the patient to bring about changes related to their IPAF.

In the ending phase (sessions 13–16), the focus is on empowering the patient so that he or she can continue the process of change after the treatment ends. The ending phase typically starts by the therapist sharing a draft “goodbye” letter that contains an overview of the patient’s presenting problems, the jointly agreed upon IPAF formulation, the changes that have been achieved in treatment, and a summary of what remains to be achieved. The patient is then invited to read the letter out loud and to suggest any changes that he or she feels are needed. The letter provides another important opportunity to work through the IPAF because it typically reactivates the patient’s IPAF. Linda, for instance, became silent when handed the letter. She read the letter, seemingly without any emotion, and said she did not have any comments on it. When I asked whether the letter conveyed the work that we had done together, she nodded. However, because she knew the letter introduced the last phase of treatment, she added that it left her feeling that I had probably had enough of her and wanted to get rid of her because there must be other, more interesting, patients who wanted to see me. When I suggested that perhaps this was Linda’s old pattern being reactivated, she nodded and said she was surprised it could still be that powerful. This statement led to in-depth exploration of how she would deal with similar experiences when her old pattern might be reactivated in the future. Much of the final few sessions was used to examine the extent to which the old pattern remained active in her daily life and the extent to which she had already internalized other ways of looking at herself and others. By the end of the treatment, she was able to express gratitude toward me and the treatment; although she still had occasional gastrointestinal problems, her symptoms had become markedly better. In the final session, she wanted to discuss whether her symptoms had biological roots and therefore might never resolve completely. She said she remembered that during our first session, I had said that I believed her symptoms were real and not imagined and that this had given her the feeling that I was truly listening to her and thus that I could help her (an example of the restoration of epistemic trust).