In the United States, substance use disorders constitute a tremendous medical and social challenge: 13.8% of all Americans will have an alcohol-related substance use disorder in their lifetime, and an estimated 7.1% (15.1 million) of Americans 12 years old or older were current users of illicit drugs in 2001. The cost to the nation exceeds $275 billion annually. We provide a general review of the subject, focusing especially on advances in diagnosis, natural history, genetics, pathophysiology, psychopathology, and treatment.

Definition

In DSM-IV-TR (

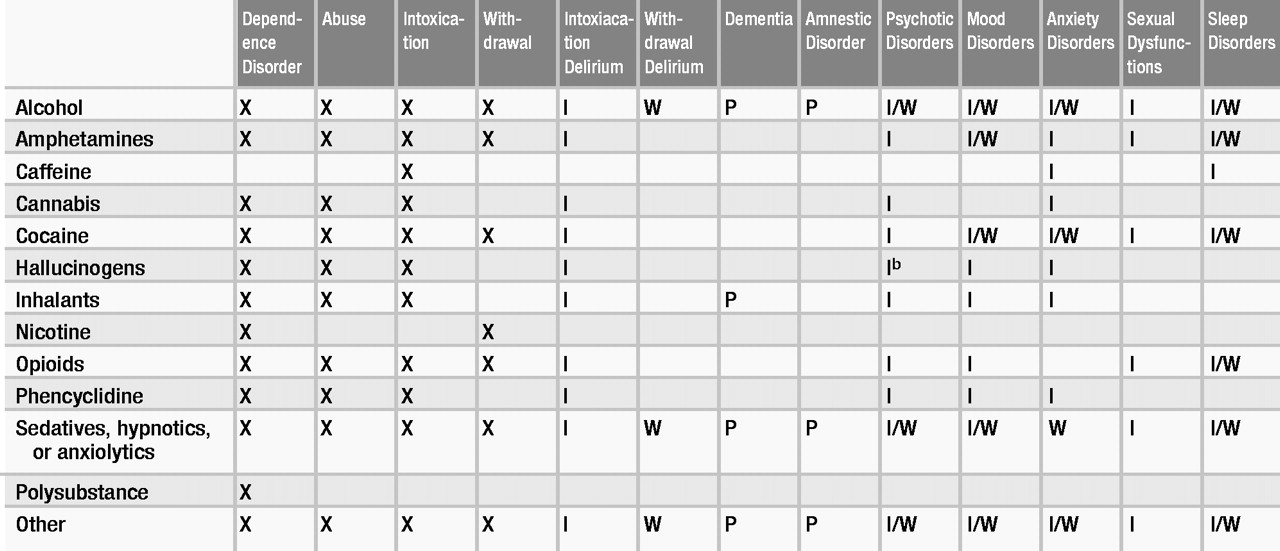

1), substance-related disorders are divided into two groups: substance use disorders, which include substance dependence and substance abuse, and substance-induced disorders, which encompass substance intoxication, substance withdrawal, and other psychiatric syndromes that are the direct pathophysiological consequence of use of a substance. DSM-IV-TR distinguishes substance-induced mental disorders from substance-induced disorders that are due to general medical conditions and those for which the causes are unknown.

DSM-IV-TR provides generic definitions for dependence, abuse, intoxication, and withdrawal and, with some exceptions, specific criteria sets for each of these states for almost all substances of abuse. For some substances, these diagnoses may be made in the absence of a specific criteria set. Table 1 indicates whether criteria sets have been established for certain states or substance combinations. Definitions of substance-induced syndromes other than intoxication and withdrawal are based on the DSM criteria for the syndromes they resemble and may be found in the relevant section of DSM-IV-TR—for example, cocaine-induced mood disorder is categorized as a mood disorder. This section addresses particular issues in the definition and diagnosis of the more complex conditions. An important caveat is that a majority of persons who use substances use more than one at a time, which complicates diagnosis.

“Addiction,” “cocainism,” and “alcoholism” are among many terms widely used to describe substance-related syndromes for which there are no DSM definitions. Nonetheless, the three terms generally refer to substance dependence, and in this review they are used to denote such conditions interchangeably with the types of substance dependence as defined in DSM-IV-TR.

Substance use disorders

Substance dependence

Dependence is a state comprising cognitive, behavioral, and physiological features that together signify continued substance use despite significant substance-related problems (Table 2). It is a pattern of repeated use lasting at least 12 months that can result in tolerance, withdrawal, and compulsive drug-taking behavior. Not all substances produce tolerance or withdrawal syndromes (see Table 1). Tolerance is the need for greatly increased amounts of a substance to produce a desired effect or a greatly diminished effect with constant use of the same amount of the substance. Withdrawal occurs when blood or tissue concentrations of a substance decline in an individual who had maintained prolonged heavy use of the substance. In this state the individual will likely take the substance to relieve or to avoid unpleasant withdrawal symptoms. Neither tolerance nor withdrawal is necessary or sufficient for a diagnosis of substance dependence, but a history of tolerance or withdrawal is usually associated with a poorer prognosis.

Substance abuse

Substance abuse as defined in DSM-IV-TR includes continued use of a substance, despite significant problems caused by its use, by an individual who does not meet criteria for substance dependence (Table 3). “Failure to fulfill major role obligations” is a criterion. To fulfill an abuse criterion, the substance-related problem must have occurred repeatedly or persistently during the same 12-month period. Substance abuse does not apply to caffeine and nicotine (see Table 1).

Substance-induced disorders

Substance intoxication and substance withdrawal are described in Tables 4 and 5, respectively. A diagnosis of a substance-induced mental disorder denotes the presence of a particular syndrome once it has been established that it is the direct result of the substance (via intoxication or withdrawal). Some disorders can persist after the substance has been eliminated from the body, but symptoms lasting more than 4 weeks after acute intoxication or withdrawal are considered manifestations either of a primary mental disorder or of a persisting substance-induced disorder. The differential diagnosis can be complicated: withdrawal from some substances (e.g., sedatives) may look like intoxication with others (e.g., amphetamines).

Alcohol

Alcohol use disorders: abuse and dependence

It is important to distinguish alcohol abuse from dependence; the prognostic implications of the two differ in terms of use, continued meeting of diagnostic criteria, and treatment. The alcohol abuser might not progress to dependence, and the alcohol-dependent person

must become abstinent (

2). Specifying whether physiological dependence is present has prognostic value, because it indicates a more severe clinical course (

3), especially when withdrawal rather than tolerance is the basis for the diagnosis of physiological dependence. The term “primary alcoholism” is used in the context of psychiatric comorbidity. It refers to alcohol dependence that has led to psychopathology, most often an anxiety or mood disorder. “Secondary alcoholism” refers to dependence on alcohol that results from self-medication for an underlying psychiatric disorder. It commonly occurs with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

Alcohol-induced disorders

The alcohol-induced disorders include intoxication, withdrawal, intoxication delirium or withdrawal delirium, withdrawal seizures, alcohol-induced persisting dementia, alcohol-induced persisting amnestic disorder (Korsakoff’s syndrome), alcohol-induced psychotic disorder, and sexual dysfunction. Alcohol intoxication is time-limited and reversible, with onset depending on tolerance, amount ingested, and amount absorbed. It is affected by interactions with other substances, medical status, culture, and individual variation.

Delirium tremens can occur during either alcohol withdrawal or alcohol intoxication. Hallucinations may be auditory and of a persecutory nature, or they may be kinesthetic. Delirium tremens can appear suddenly, but usually it occurs gradually 2–3 days after cessation of drinking and reaches its peak intensity on day 4 or 5. It is usually benign and short-lived, subsiding after 3 days in the majority of cases, although subacute symptoms may last weeks. The fatality rate is estimated at less than 1%. Delirium tremens is associated with infections, subdural hematomas, trauma, liver disease, and metabolic disorders. If death occurs during delirium tremens, the cause is usually infectious fat embolism or cardiac arrhythmia (usually associated with hyperkalemia, hyperpyrexia, and poor hydration). Alcohol withdrawal seizures that are not a part of delirium tremens generally occur between 7 and 38 hours after the last alcohol use in chronic drinkers; the average is about 24 hours after the last drink. About 10% of all chronic drinkers experience a grand mal seizure at some time; of these, one-third go on to delirium tremens, and 2% go on to status epilepticus. Alcohol lowers the seizure threshold, which likely contributes to these seizures.

Thiamine deficiency associated with prolonged heavy alcohol use produces alcohol-induced persisting amnestic disorder, or Korsakoff’s syndrome, and its associated neurological deficits—peripheral neuropathy, cerebellar ataxia, and myopathy. Korsakoff’s syndrome often follows acute Wernicke’s encephalopathy—confusion, ataxia, nystagmus, ophthalmoplegia, and other neurological signs. As the encephalopathy subsides, severe impairment of anterograde and retrograde memory remains; confabulation is common. Early treatment of Wernicke’s encephalopathy with large doses of thiamine may prevent the development of Korsakoff’s syndrome.

Sedatives, hypnotics, and anxiolytics

These substances induce syndromes generally like those induced by alcohol, but their pharmacokinetics differ from alcohol’s in significant ways. Physical dependence on substances of this class is a predictable phenomenon that is closely related to dosage, half-life, and duration of use. At therapeutic doses, dependence may occur over the course of weeks, but at higher doses dependence develops more rapidly. The benzodiazepines vary in terms of half-life and predominant pharmacokinetics, leading to different abuse potentials. Salzman has provided a review (

4).

Sedative, hypnotic, or anxiolytic withdrawal is a characteristic syndrome that develops in response to a relative decrease in intake after regular use. Grand mal seizures occur in 20%–30% of untreated individuals. The withdrawal syndrome produced by substances in this class may present as a life-threatening delirium.

Opioids

Opioid use disorders

Opioids refers to all drugs in this class, including heroin, morphine, synthetic drugs, and others. Most individuals with opioid dependence have significant tolerance and experience withdrawal. As noted in Table 1, there are no specific criteria for the diagnosis of opioid dependence or abuse other than the generic criteria. A diagnosis of dependence rather than of abuse is called for when use is accompanied by compulsive behavior related to opioids.

Opioid-induced disorders

Opioid intoxication and overdose are reversible by the administration of naloxone. Opioid withdrawal is a syndrome that follows a relative reduction in heavy and prolonged use. The syndrome begins within 6–8 hours after the last dose and peaks between 48 and 72 hours; symptoms disappear in 7–10 days. The signs and symptoms are the opposite of those of the acute agonist effects: lacrimation, rhinorrhea, pupillary dilation, piloerection, diaphoresis, diarrhea, yawning, mild hypertension, tachycardia, fever, and insomnia (Table 6). A flulike syndrome subsequently develops, with complaints, demands, and drug seeking. Uncomplicated withdrawal is usually not life-threatening unless a severe underlying disorder, such as cardiac disease, is present. Withdrawal occurs in 60%–94% of neonates of opioid-addicted mothers, beginning 12–24 hours after birth and sometimes persisting for months.

Cocaine

Cocaine can be chewed in the form of coca leaves, smoked in the form of coca paste, inhaled or injected as cocaine hydrochloride powder, or smoked in a cocaine alkaloid form (“freebase,” or “crack”). “Speedballing”—mixing cocaine and heroin—is particularly dangerous because of the potentiation of respiratory depressant effects.

Cocaine use disorders

Cocaine use can quickly produce dependence. With cocaine’s short half-life, frequent use is needed to maintain the high. Tolerance occurs with repeated use. The intensity and frequency of cocaine use are less in abuse than in dependence.

Cocaine-induced disorders

Cocaine-induced states must be clearly differentiated from schizophrenia, mood disorders, and anxiety disorders. Cocaine’s autonomic stimulant effects are more common than its depressant effects, which emerge only with chronic high-dose use. In overdose, cocaine’s effects on the noradrenergic system are significant and produce muscular twitching, rhabdomyolysis, seizures, cerebrovascular accident, myocardial infarction, arrhythmia, and respiratory failure. Metabolism is slowed when cocaine is combined with alcohol (producing cocaethylene), which increases the risk of death by 18 to 25 times. Tolerance to cocaine’s euphoric effects can develop during a binge. Often amphetamine or phencyclidine intoxication can be distinguished from cocaine intoxication only through toxicological studies. EEG abnormalities may be present during withdrawal from cocaine. Cocaine intoxication delirium may occur within 24 hours of use. Cocaine intoxication delirium and cocaine-induced psychotic disorder (usually with delusions) are not uncommon and should be kept in mind when evaluating patients with delirium or psychosis.

Amphetamines

In the DSM-IV-TR, amphetamines, which have a substituted-phenylethylamine structure (e.g., amphetamine, dextroamphetamine, and methamphetamine), are grouped with amphetamine-like substances that are structurally different, such as methylphenidate.

Amphetamine-induced disorders

In amphetamine intoxication, behavioral and psychological changes are accompanied by significant physiological and CNS syndromes. The state begins no more than 1 hour after use, depending on the drug and the method of delivery. “Perceptual disturbances” should be specified when hallucinations or illusions occur in intoxication without delirium if reality testing is intact. If hallucinations or illusions are accompanied by impaired reality testing, the diagnosis of amphetamine-induced psychotic disorder with hallucinations should be considered. Differentiating between amphetamine-induced psychosis and schizophrenia can be difficult (

5).

Phencyclidine and ketamine

Variations of phencyclidine (PCP) include its thiophene analogue TCP (thienyl-cyclohexylpiperidine) and ketamine. These substances can be used orally or intravenously, and they can be smoked and inhaled. PCP is often mixed with other substances such as amphetamines, cannabis, cocaine, or hallucinogens.

Phencyclidine use disorders

Although the DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for PCP dependence include the first seven items of the generic definition of substance dependence, criteria 2A and 2B may not apply, given that a clear-cut withdrawal pattern is difficult to establish. Adverse reactions to PCP, as with hallucinogens, may be more common among individuals with preexisting mental disorders. PCP dependence may have a rapid onset.

Phencyclidine-induced disorders

PCP intoxication produces both sympathetic and cholinergic effects. Intoxication begins within 5 minutes of use and peaks within 30 minutes. High-dose intoxication and overdose can produce hyperthermia and involuntary movements followed by amnesia, and coma, analgesia, seizures, and respiratory depression at the highest doses (i.e., greater than 20 mg). Because PCP is lipophilic, intoxication may persist for days. Mydriasis and nystagmus (vertical more than horizontal) are characteristic of PCP use. Perceptual disturbances should be specified if present. Psychosis is the most common PCP-induced mental disorder. Chronic psychosis may occur, along with long-term neuropsychological deficits.

Hallucinogens

This diverse group of substances includes indolamine derivatives (LSD, morning glory seeds), phenylalkylamine derivatives (mescaline, STP [2,5-dimethoxy-4-methylamphetamine], and ring-substituted amphetamines—MDA [methylenedioxyamphetamine; “old ecstasy”], MDMA [methylenedioxymethamphetamine; new “Ecstasy”], MDEA [methylenedioxyethamphetamine]), indole alkaloids (psilocybin, DMT [dimethyltryptamine]), and miscellaneous other compounds. Hallucinogens are usually taken orally, although dimethyltryptamine is smoked and sometimes injected.

Hallucinogen-induced disorders

In hallucinogen intoxication, perceptual changes occur alongside full alertness during or shortly after use. Changes include subjective intensification of perceptions, depersonalization, derealization, illusions, hallucinations, and synesthesias. DSM-IV-TR diagnosis requires the presence of at least two of seven physiological signs. Hallucinations are usually visual, often involving geometric forms but sometimes involving persons and objects. Auditory or tactile hallucinations are rare. Reality testing is usually preserved.

Hallucinogen persisting perception disorder (“flashbacks”) after cessation of hallucinogen use involves the reexperiencing of one or more of the same perceptual symptoms experienced while originally intoxicated. These are usually fleeting events, but in rare instances they may be lasting. Symptoms may be triggered by stress, drug use (including that of other drugs), or sensory deprivation, and they may be triggered intentionally. Psychotic disorder not otherwise specified is the proper diagnosis if the patient interprets the perceptions as reality or having origins that are unreal.

Cannabis

Cannabis-induced disorders

The cannabis class includes substances such as marijuana, hashish, and purified delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). Usually smoked, these may also be mixed with food and eaten. Intoxication peaks 10–30 minutes after smoking cannabis and lasts about 3 hours. As lipophilic molecules, cannabinoids and their metabolites have a half-life of approximately 50 hours, and their effects may persist for 12–24 hours. At least two of the following signs develop within 2 hours of use: conjunctival injection, increased appetite, dry mouth, and tachycardia. Intoxication with CNS depressants (including alcohol, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, and other drugs), unlike with cannabis, usually decreases appetite, increases aggressive behavior, and produces nystagmus or ataxia. At low doses, hallucinogen intoxication may resemble cannabis intoxication. Acute adverse reactions to cannabis should be differentiated from panic, major depressive disorder, delusional disorder, bipolar disorder, and paranoid schizophrenia.

Cannabis-induced delusional disorder is a syndrome that may occur soon after use. It may be associated with persecutory delusions, marked anxiety, depersonalization, and emotional lability and is often misdiagnosed as schizophrenia. Subsequent amnesia of the episode can occur. Chronic use can cause a syndrome resembling dysthymic disorder.

Nicotine

Nicotine has euphoric effects and reinforcement properties similar to those of cocaine and opioids, and its use can lead to dependence. Nicotine withdrawal develops when use is stopped or reduced after a prolonged period (at least several weeks) of daily use. The withdrawal syndrome includes four or more of the following: dysphoric or depressed mood; insomnia; irritability, frustration, or anger; anxiety; difficulty concentrating; restlessness or impatience; decreased heart rate; and increased appetite or weight gain. After cessation, heart rate decreases 5–12 beats per minute within a few days, and weight increases on average 2–3 kg over the course of the first year.

Inhalants

This class of substances includes the aliphatic and aromatic hydrocarbons found in products such as gasoline, glue, paint thinners, and spray paints; the halogenated hydrocarbons found in cleaners, correction fluid, and spray-can propellants; and other volatile compounds containing esters, ketones, and glycols.

Inhalant use disorders

All of the substances in this class may produce dependence, abuse, or intoxication. There are no specific criteria sets for dependence or abuse of inhalants, partially because of uncertainty about whether tolerance or withdrawal syndromes develop with use of these substances.

Inhalant-induced disorders

Inhalant intoxication involves clinically significant behavioral or psychological changes accompanied by dizziness or visual disturbances, nystagmus, incoordination, slurred speech, unsteady gait, tremor, and euphoria. Higher doses of inhalants may lead to the development of lethargy and psychomotor retardation, generalized muscle weakness, depressed reflexes, stupor, or coma. Inhalant-induced mental disorders may be characterized by symptoms that resemble primary disorders. Mild to moderate intoxication with inhalants can be similar to intoxication caused by CNS depressants.

Caffeine

There is no DSM-IV-TR diagnosis for caffeine dependence or abuse. Although withdrawal headaches may occur, they are usually not severe enough to require treatment. Doses leading to caffeine intoxication can vary. At massive doses, grand mal seizures and respiratory failure can result. In persons who have developed tolerance, intoxication may not occur despite high caffeine intake. DSM-IV-TR recognizes other caffeine-induced disorders such as anxiety disorder and sleep disorder, and there is a category for caffeine-related disorder not otherwise specified.

Other (or unknown) substance-related disorders

The DSM-IV-TR category of other (or unknown) substance-related disorders encompasses symptoms that result either from use of a substance whose identity is unknown when the patient presents or from use of a substance that belongs to a class that does not have its own category. Examples of the latter include amyl nitrate, anticholinergic medications, gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB) (discussed below in Epidemiology and Natural History), corticosteroids, anabolic steroids (

6), antihistamines, and a growing list of prescription drugs (e.g., angiotensin-converting enzyme [ACE] inhibitors, fluoroquinolones, and others) (

7).

Polysubstance dependence

The DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of polysubstance dependence is used when an individual has, within the past year, repeatedly used at least three classes of substances (excluding nicotine and caffeine) without one predominating. Dependence is global and not for any one drug. There is no category of polysubstance abuse.

Psychiatric comorbidity

Dual diagnosis patients are those who have a substance abuse disorder and another major psychiatric diagnosis. Among the major psychopathologies, the reported odds ratios for comorbid substance use are 2 for major depressive disorder, 3 for panic disorder, 5 for schizophrenia, and 7 for bipolar illness (

8).

Affective disorders

Prognosis is worsened by the presence of untreated major depression in a patient with primary alcoholism and by the presence of secondary alcoholism in a patient with primary depressive disorder. One study conducted with a large population of alcoholic patients found that primary major depressive episodes were more likely to occur in patients who were female, white, and married, who had experience with fewer drugs and less treatment for alcoholism, who had attempted suicide, and who had a close relative with a major mood disorder (

9). Differentiating between primary and secondary alcoholism thus has clinical significance.

The prevalence of major depression ranges from 17% to 30% among persons who are addicted to heroin and is considerably higher among those being treated with methadone. Depressive episodes often are mild, may be related to treatment seeking, and frequently are stress related. In one study, depression was found to be a poor prognostic sign at 2.5-year follow-up in patients addicted to opioids, except in those who had coexistent antisocial personality; for this group, the presence of depression actually improved prognosis (

10).

Affective disorders have been concurrently diagnosed in 30% of cocaine addicts, with a significant proportion of these patients having bipolar or cyclothymic disorder. One group has found that alcohol abuse may be more associated with depression, whereas cannabis abuse may be more commonly associated with mania (

11).

Psychosis

Psychotic symptoms can result from the use of a wide range of psychoactive substances. Various studies have shown that 50%–60% of schizophrenia patients and 60%–80% of bipolar patients abuse substances (

12). Persons with schizophrenia also are more likely than the general population to use tobacco and caffeine. Tobacco use has been associated with lowering of blood levels of neuroleptics. Among patients with cocaine dependence, craving is higher among those with schizophrenia than among those without schizophrenia (

13).

Anxiety disorders

The relationship between anxiety and substance use has undergone a great deal of study, and the recent literature has focused particularly on substance use in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). After the disasters of September 11, 2001, an increase was observed in relapse and in new use of substances (

14). Alcohol and substance use can increase vulnerability to PTSD, and PTSD can worsen alcohol and drug problems. Pfefferbaum and Doughty (

15) found that after the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing, alcohol use among victims increased. Alcohol use was not successful in alleviating symptoms in these individuals, and in fact it increased functional impairment. For a general review of anxiety and alcoholism, see Frances and Borg (

16).

Neuropsychiatric disorders

Chronic abuse of alcohol, sedatives, or inhalants has been correlated with brain damage and neuropsychological impairment. Such impairment may be obvious (as in alcohol dementia and Korsakoff’s syndrome) or relatively mild and detectable only by neuropsychological testing. Cognitive impairment may be short-lived and recede after 3–4 weeks of abstinence, may improve gradually over several months or years of abstinence, or may be permanent.

Epidemiology and natural history

In 2001, some 7.1% (15.1 million) of Americans 12 years old or older were current users of illicit drugs, up from 6.3% in 2000 (

17). In the most recent estimates of substance use disorder diagnoses (1999), 3.6 million Americans met diagnostic criteria for dependence on illicit drugs, and 1.1 million of these were 12 to 17 years old (

18). Drug abuse deaths reported to the Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN) have increased in all metropolitan areas in recent years (

19). In the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study, 30% of alcoholic individuals also met criteria for another substance use disorder. The actual monetary cost to the nation is estimated to exceed $275 billion annually.

The large-scale studies that have produced data on substance use disorders include DAWN (

19), the Monitoring the Future study, which focuses on American adolescents and young adults (

20); the National Household Survey (

18); the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study (

21); and the National Comorbidity Survey (

22).

Alcohol

The Epidemiologic Catchment Area study found that 13.8% of Americans will have an alcohol-related substance use disorder in their lifetime. At least 9 million Americans are alcohol dependent, and another 6 million abuse alcohol. The annual costs attributed to alcohol use disorders exceed $166.5 billion annually (

23).

Vaillant’s (

24) studies found that some alcohol abusers drink until death, others stop drinking, and still others display a pattern of long abstinence followed by relapses. Risk-taking, sensation-seeking individuals are thought to be at particularly high risk of developing alcoholism. It has been established that alcoholism occurs in families, but the mode of transmission is unknown.

Biological markers may identify those at risk of developing alcohol use disorders. There is evidence that alcohol ingestion by not-yet-alcoholic children of alcoholics produces less subjective feelings of intoxication, less impairment of motor performance, less body sway or static ataxia, and less change in cortisol and prolactin levels than it does in others (

25). There is also evidence of low-amplitude P300 event-related potential in alcoholic persons and in abstinent sons of alcoholic men.

Complications

Morbidity and mortality due to alcohol are high, especially given the effects of alcohol use on violence and on liver disease (

26). About 25% of general hospital admissions are related to chronic alcohol use.

Violence. There is a strong association between alcohol and violence. The suicide rate among persons with alcoholism is 5%–6%. Nearly 50% of violent deaths in the United States, including traffic fatalities, are linked with alcohol (

27,

28). In 2001, more than 1 in 10 Americans, or 25.1 million persons, reported having driven under the influence of alcohol at least once in the preceding 12 months (

17).

Gastrointestinal effects. Alcoholism is the leading risk factor for cirrhosis, which occurs in 10% of alcoholic persons. Of patients who have chronic pancreatitis, 75% have an alcohol use disorder. Alcoholic hepatitis has a 5-year mortality rate of 50% (

29).

Hematological effects. Alcoholism is part of the differential diagnosis for anemia, especially megaloblastic anemia. Alcohol impairs immune function and promotes oropharyngeal, esophageal, gastric, hepatic, breast, and pancreatic cancer.

Endocrinological effects. Alcohol affects male sexual function and fertility directly, through effects on testosterone levels, and indirectly, through testicular atrophy. Increased levels of estrogen in men lead to gynecomastia and body hair loss. In women there may also be severe gonadal failure. Hypoglycemia may result from excessive alcohol ingestion.

Neurological effects. Alcohol increases blood pressure and is associated with an increased risk of cerebrovascular accident. Alcoholic cerebellar degeneration is a slowly evolving condition in patients with a long-standing history of excessive alcohol use. Alcoholic peripheral neuropathy is characterized by stocking-and-glove paresthesia with decreased reflexes and autonomic nerve dysfunction. Other long-term neurological effects of alcoholism include central pontine myelinolysis, Marchiafava-Bignami disease, and muscular pathology.

Cardiovascular effects. Heavy drinkers have an elevated risk of cardiomyopathy and heart failure and lower post–myocardial infarction survival rates. On the other hand, moderate use of alcohol may have beneficial effects on both the risk of heart failure in the elderly (

30) and on postinfarction mortality risk (

31).

Sedatives, hypnotics, and anxiolytics

Abuse of the substances in this category is often iatrogenic. Chronic sedative abuse can produce “blackouts” and neuropsychological damage similar to those seen in alcoholic patients (

32). This class of drugs may cause hypotension, sedation, cerebellar toxicity, psychomotor impairment (especially in the elderly), cognitive impairment, and, of course, dependence. The potential for morbidity and mortality is increased when these substances are used along with other CNS depressants. Flunitrazepam (trade name, Rohypnol) is a highly potent benzodiazepine sold outside the United States that is also used as a “date rape” drug because it produces anterograde amnesia (

33).

Opioids

Lifetime heroin prevalence estimates were 2.3 million in 1979, 1.7 million in 1992, 2 million in 1997, and 2.4 million in 1998 (

18). The Epidemiologic Catchment Area study showed that opioid use was greater among males, who were found to be three to four times as likely as females to use drugs of this type. Greater associated psychopathology is found in cultural groups in which heroin is less endemic. The course of heroin addiction generally involves an interval of 2–6 years between regular use and treatment seeking.

Complications

Impurities and contaminated needles may lead to endocarditis, septicemia, pulmonary embolism, pulmonary hypertension, skin infections, hepatitis B, and HIV infection. Because of infection, homicide, suicide, overdose, and AIDS, the death rate of young addicts is 20 times higher than that of nonaddicts.

Cocaine

In 1999 an estimated 1.5 million Americans over the age of 12 years were current cocaine users (

18). Estimated current “crack” cocaine users numbered 413,000 in 1999 (

15). More men than women use cocaine. The time from first intranasal use to cocaine addiction is 4 years in adults, but less in adolescents. The proportion of cocaine users in the United States underwent a statistically significant increase from 0.5% to 0.7% between 2000 and 2001 (

17).

Complications

Violence. Cocaine was found to have been used immediately prior to death in 20% of suicides in New York City in the 1990s (

34). Cocaine has also been detected in the urine of homicide victims, in persons arrested for murder, and in persons who have died from overdoses of other drugs.

Psychopathology. Chronic cocaine use depletes all neurotransmitters, leading to increased receptor sensitivity to dopamine and norepinephrine, which is associated with depression, fatigue, poor self-care, low self-esteem, low libido, and mild parkinsonism. Psychosis, an attention-deficit syndrome, and stereotypies may result from continued use. Levels of pathological gambling among cocaine-dependent patients have been found to be five times greater than in the general population (

35).

Medical. Whether used intranasally, smoked, or injected, cocaine can lead to a variety of complications, including death, even in recreational, low-dose users. Acute complications include agitation, myocardial infarction, diaphoresis, tachycardia, QRS prolongation, subarachnoid hemorrhage, metabolic and respiratory acidosis, arrhythmia, grand mal seizure, and respiratory arrest. There is evidence of cerebrovascular disease secondary to chronic use (

36). Chronic complications of intranasal abuse include nasoseptal defects and dental neglect as a result of cocaine’s anesthetic properties. Intravenous use may produce any of the sequelae of unsterile technique or contaminants.

Amphetamines

Some 4.7 million Americans have tried methamphetamine (

18). Amphetamine abuse may start as attempts to lose weight or to increase energy. The long-term sequelae of amphetamine use mimic those of cocaine. Intravenous administration can produce the same medical complications as with other drugs.

Phencyclidine and ketamine

Chronic use of PCP may lead to neuropsychological deficits, psychotic episodes, and violence. Use of ketamine is growing, especially among youths and young adults. Ketamine and its active metabolite, norketamine, act at many CNS receptor sites, including the

N-methyl-

d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor. Ketamine is taken intranasally or orally. It quickly creates dissociation, and it may produce psychosis in normal individuals (

37). The acute medical effects of both PCP and ketamine can be serious; they may produce neurological toxicity, rhabdomyolysis, and sympathetic stimulation. Respiratory arrest or apnea also can occur, with a risk of aspiration. In cases of death from overdose, pulmonary edema has been noted.

Hallucinogens

In 1999 there were an estimated 1.2 million new hallucinogen users in the United States, and the rate of current use nationwide was 0.4%. The number of persons reporting that they had ever tried Ecstasy (MDMA) increased from 6.5 million in 2000 to 8.1 million in 2001 (

17).

Most hallucinogens can produce acute adverse effects (e.g., the “bad trip”). Hallucinogen use can also lead to chronic effects, including prolonged psychotic states that resemble psychosis or mania. Flashbacks, another potential chronic sequela of hallucinogen use, occur in 15%–30% of chronic users. Some of the drugs in this class, such as MPTP, have produced permanent parkinsonism by selective destruction of the substantia nigra.

MDMA, a serotonin releaser and serotonin reuptake inhibitor, may produce acute, fulminant states that variously include hepatotoxicity, disseminated intravascular coagulation, cardiotoxicity, hyperthermia, rhabdomyolysis, catatonia, and acute respiratory distress syndrome (

38–

42). There is growing evidence that MDMA causes neurodegeneration in users, affecting serotonin and possibly dopamine transmission (

43). Animal models of CNS exposure to MDMA have complemented these findings (

44).

Cannabis

Cannabis accounts for 75% of illicit drug use in the United States. Frequent users numbered 6.8 million in 1998, significantly more than in 1995, when there were 5.3 million (

18). Marijuana use underwent a statistically significant increase from 4.8% to 5.4% between 2000 and 2001 (

17).

Several acute neuropsychological changes and deficits have been identified with marijuana intoxication. Decreases in complex reaction-time tasks, digit-code memory tasks, fine motor function, time estimation, the ability to track information over time, tactual form discrimination, and concept formation have been found.

Chronic cannabis users have significant impairment of memory and attention that are persistent and worsen with ongoing use. CNS imaging in cannabis users has demonstrated altered function, blood flow, and metabolism in prefrontal and cerebellar regions (

45). In cannabis users, emotional symptoms of anxiety, confusion, fear, and increased dependence can progress to panic or frank paranoid pathology. It can be a risk factor for schizophrenia or schizoid traits in vulnerable individuals. In a study that reassessed subjects from the 1980 Baltimore Epidemiologic Catchment Area study between 1994 and 1996, cannabis abusers were found to be four times as likely as nonusers to have depressive symptoms (

46). Cannabis use increases the risks of endocrine, pulmonary, reproductive, vascular, and cancerous disease.

Nicotine

Tobacco use is the leading cause of preventable morbidity and mortality in the United States, causing approximately 430,000 deaths annually (

47). Breslau et al. (

48) provide epidemiological evidence of nicotine’s addictive potential by demonstrating that nearly half of those who ever smoked tobacco for a month or more before adulthood developed nicotine dependence. Patients with psychiatric problems and substance abuse disorders are likely to remain dependent on nicotine.

The prevalence of nicotine use is increasing: in 1999 an estimated 30.2% of Americans used cigarettes, up from 27.7% in 1998. An estimated 66.5 million Americans aged 12 years or older reported current use of a tobacco product in 2001; this number represents 29.5% of the population (

17). Cigarette use is decreasing among men, but increasing among women. Of the 2.1 million Americans who began smoking cigarettes in 1997, most were under age 18 (

18).

Inhalants

Inhalant use stabilized in 1996 after having increased for 4 years (

20). Most users cease use quickly and move to other substances. Intoxication may produce aggressive, disruptive, antisocial behavior. Deaths have been reported from inhalant-induced CNS depression of the respiratory system, cardiac arrhythmia, and accidents. CNS studies using single photon emission computed tomography have documented the presence of abnormal perfusion in former users (

49). Dermal or mucosal frostbite may occur after inhalation of fluorinated hydrocarbons from refrigerants or propellants (

50).

Other substances

Gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB), a metabolite of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), is a schedule I substance that is increasingly used worldwide as a recreational drug by party and nightclub attendees, as a growth hormone releaser by bodybuilders, and as a “date rape” drug. GHB increases CNS dopamine levels and has effects in the endogenous opioid system. GHB toxicity includes coma, seizures, respiratory depression, vomiting, anesthesia, and amnesia (

51). The drug is missed in routine diagnostic urine screening. Although full recovery usually occurs, the toxic state is life threatening and may be complicated by severe muscular pathology leading to rhabdomyolysis and myoglobinuria (

52). An growing number of reports have described clinically significant states of withdrawal from GHB (

53). GHB occasionally leads to seizures, from which the user rapidly recovers. With the recent approval of the indication of GHB (under the name Xyrem) for the treatment of narcolepsy (

54), GHB abuse may increase.

Rehabilitation

The rehabilitation model, pioneered in substance abuse treatment, has become an important organizing paradigm for a variety of categories of psychiatric illness. It combines self-help, counseling, education, relapse prevention, group treatment, a warm and supportive environment, and emphasis on a medical model geared toward reducing stigma and blame. Most treatment programs are highly structured, insist on the goal of abstinence, and offer lectures, films, and discussion groups as part of a complete cognitive and educational program. Patients frequently become active members of 12-step programs and are encouraged to continue in aftercare.

Special populations

Women

Women with substance use disorders suffer greater secondary medical morbidity from substance use (

116) and suffer a higher mortality rate by all causes (including suicide). Female alcohol abusers start later than men, progress to abuse faster, abuse less total alcohol, and have higher rates of comorbid psychopathology. Comorbid psychopathology in women with substance use disorders more often involves anxiety disorders (particularly PTSD), mood disorders, and eating disorders (

117). Women are more likely to have a significant other who is also a substance abuser. They also tend to have a history of sexual or physical abuse and to date the onset of their substance use disorder to a stressful event.

Alcohol’s neurotoxic effects may be greater in women than in men (

118). Sexual function is affected by almost all drugs of abuse, and sexual function improves with sobriety (

119). For unknown reasons, women alcohol abusers have a higher risk of developing breast cancer than nonabusers (

120).

Prenatal exposure to alcohol remains one of the leading preventable causes of birth defects, mental retardation, and neurodevelopmental disorders (possibly including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder [(

121]) in the United States (

122). The treatment of neonates for methadone withdrawal is a common procedure; thus, methadone use is not an absolute contraindication to becoming pregnant (

123). Finally, despite intense debate, it is becoming increasingly apparent that that babies of cocaine-using mothers are at risk of neurodevelopmental deficits (

124).

Treatment services

Large-scale studies have suggested that women with substance-related disorders are undertreated (

125). In one group of pregnant women with identified psychiatric or substance use disorders, a very poor rate of treatment for substance use (23%) was observed (

126).

Children and adolescents

Substance use disorders among adolescents constitute a significant public health problem. The prevalence of substance use disorders is rising, the age at first use is dropping, and morbidity and mortality among youths with substance use disorders are increasing (

127). In 2001, 10.8% of youths 12 to 17 years of age were current drug users, compared with 9.7% in 2000. Similarly, among adults 18 to 25 years of age, current drug use increased from 15.9% to 18.8% between 2000 and 2001 (

17).

Diagnosis of substance dependence in adolescents is difficult, because adolescents are less likely to report withdrawal symptoms, have shorter periods of addiction, and may recover more rapidly from withdrawal. Among children and adolescents, the family is a very important unit for conceptualizing influences that promote substance use and for conceptualizing treatment (

128–

131).

The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry’s practice parameters for substance use disorders provide the basis of the care of adolescents (

132). In addition, the American Academy of Pediatrics has established guidelines for the assessment, treatment, and referral of such problems (

133), and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration has published a guide (

134). For details about general aspects of adolescent substance use disorders, particularly epidemiology, risk factors, genetics, prevention, and neurobiology, the reader is referred to other sources (

135,

136).

Epidemiology

Until late 2002, epidemiological studies on adolescent substance abuse had found few positive findings. Among the findings from the best available studies from recent years are that 7%–17% of adolescents 13 to 18 years old meet DSM criteria for substance abuse or dependence (

137) and that alcohol use (

17) and substance use in general (

138) are widespread among adolescents. However, preliminary data from 2001 suggest that there may be significant declines in use of some substances in many age groups (

17).

Psychiatric comorbidity

Most adolescents in substance treatment programs have comorbid psychopathology, including conduct disorder, depression, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and others. The Oregon Adolescent Depression Project (

139) found that 66.2% of adolescents with a substance use disorder also had a psychiatric disorder but that only 31.3% of those with a psychiatric disorder had a substance use disorder. Substance use disorders are a major risk factor for suicide and suicide attempts among adolescents. The use of methylphenidate in the treatment of ADHD in adolescents has been found to significantly reduce their risk of developing substance abuse in later life (

140).

Bipolar disorder in adolescence may be a major risk factor for adult substance use disorders. Biederman et al. found that adolescent-onset bipolar disorder was associated with a greater risk of later having a substance use disorder than child-onset bipolar disorder, regardless of whether conduct disorder was present (

141). Geller conducted a double-blind, placebo-controlled, random-assignment, parallel-group, pharmacokinetically dosed study of lithium treatment for adolescents with bipolar disorders and temporally secondary substance dependence disorders (

142). Those who received lithium had better outcomes in terms of relapse than those who received placebo, indicating the utility of lithium in bipolar disorder in adolescents and perhaps also in adolescents with primary substance use disorders (

143).

Treatment issues

Adolescent programs rely heavily on peer support groups, family therapy, organized education, education on drug abuse, 12-step programs such as AA and Alateen, vocational programs, patient-staff meetings, and activity therapy (

136). Predictors of treatment completion include greater severity of alcohol abuse, worse abuse of drugs other than alcohol, nicotine, or cannabis; a higher degree of internalizing problems, and lower self-esteem (

143).

Interpersonal therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy (

144) approaches have been shown to be generally valuable and efficacious for adolescents. Motivational enhancement therapy, originally developed for adults, has been applied to adolescents (

145). Contingency management, in which the patient is rewarded for proof of abstinence, is also effective (

146). Few investigations of group therapy among adolescent alcohol abusers have been conducted, although this modality’s efficacy has been documented (

147,

148). Among the structured group psychotherapies, cognitive behavioral therapy groups have been shown to be superior to interactional groups in reducing use (

149). Twelve-step programs geared to younger persons may be of benefit for the few adolescents who have sufficient insight.

The elderly

The incidence of alcoholism is lower among the elderly (perhaps because persons with chronic alcoholism die prematurely), but the abuse of prescription drugs is common. In addition, age-related changes in the pharmacokinetics of prescribed medications compound the consequences of substance abuse in the elderly.

Abuse of benzodiazepines and other hypnotics is common. Cognitive decline may lead to unintentional misuse. Nursing home patients are sometimes overmedicated to reduce disruptiveness. Abusers of prescription medications may require hospitalization to discontinue use.

The chronically mentally ill

Chronic mental illness frequently contributes to the chronicity and severity of substance abuse problems. Facilities that combine psychiatric treatment with substance abuse rehabilitation techniques are often unavailable to these patients. Severely disturbed abusers may be shunned by drug rehabilitation units. Confrontational methods and overemphasis on abstinence, which may lead to underuse of appropriate psychotropic medications, can be detrimental to mentally ill substance abusers.

Mildly retarded patients (those with an IQ in the range of 60–85) are concrete in their thinking, are easily manipulated, and may have problems learning from experience. Most of these patients live in the community, and they may attempt to socialize in neighborhood bars, which are viewed as warm and nonjudgmental social environments. An emphasis on providing acceptance, warmth, and emotional support is especially important in working with this population.

The homeless population is no longer principally composed of “skid row” alcoholics or single, older, chronically alcoholic men (

150). The population is now younger and includes a growing proportion of women. In addition, as many as 90% of homeless persons have a primary psychiatric diagnosis. In various urban samples in the United States, 20%–60% of homeless patients reported alcohol dependence (

150).

Minorities

Substance use disorders have a major impact on overall life expectancy among blacks, Hispanics, and Native Americans (

151). Black teenagers report less alcohol abuse than do their white peers; in their twenties and thirties, however, rates of abuse among blacks are comparable to those of whites, and blacks suffer a disproportionate degree of medical (notably cirrhosis, esophageal cancer, and AIDS), psychological, and social sequelae. Excessive alcohol consumption is reported among rural and urban Native Americans (

152).

Future directions

Over the past two decades, American medicine has seen tremendous developments in the understanding and treatment of substance-related disorders, and further developments are promising. The neurobiology of addiction will likely be further refined in terms of specific neuroanatomical effects of specific substances. Other areas currently being investigated include variation in pharmacokinetics, especially in hepatic metabolism, and genetic factors in addiction. The effects of the newest drugs of abuse—MDMA, GHB, and others—will need a great deal of attention in the coming years.

Investigation of optimal treatment planning will be informed by ongoing studies comparing existing treatment modalities. Ideally, particular modalities can be used for specific diagnoses, psychiatric comorbid states, and socioeconomic groups. Expansion of treatment options with opiate antagonists or buprenorphine may become a reality soon (

153). Interesting developments in novel treatment strategies include vaccines against cocaine (

154), corticotropin-releasing hormone antagonists to decrease cocaine and heroin addiction, (

155), and antagonists to cannabinoid receptors to block the effects of cannabis. Thus the future of addiction psychiatry is bright and promises greater understanding, refinements of established treatments, and the creative development of novel therapies for this costly group of disorders.