One important measure of the clinical relevance of a diagnostic system is the ability of the diagnostic criteria to predict the course of problems over time (

1,

2). This attribute of predictive validity facilitates clinical decisions about whether an intervention is appropriate and establishes a baseline against which the outcomes associated with treatment can be evaluated. The optimal study of the course associated with a diagnostic system requires a large group of subjects who are evaluated over an appropriately long period of time.

Only a decade or so has passed since the publication of the DSM-III-R criteria for substance use disorders. This 1987 diagnostic system included abuse/dependence criteria that were markedly different from those of prior classifications (

3,

4). In 1994, DSM-IV modified that diagnostic approach yet again (

5–

7).

Only a few prospective investigations to determine the prognostic meaning of the DSM-IV alcohol abuse/dependence criteria have been carried out. One study evaluated 1-year outcomes for 876 men and women in the general population of New Jersey who reported consuming five or more drinks on at least one occasion over the prior year (

8,

9). Among the 239 subjects who met the criteria for alcohol dependence at the time of the initial evaluation, a 1-year follow-up revealed that 71% continued to manifest at least one of the 11 DSM-IV abuse or dependence criteria (thus fulfilling criteria for the continuation of dependence) and 29% had been free from these problems during the interval. Among the 67 men and women who initially met the criteria for abuse, 33% continued to have enough problems to maintain that diagnosis over the subsequent year, 6% went on to develop alcohol dependence, and 61% reported that they had experienced none of the 11 DSM-IV abuse/ dependence criteria. The 570 individuals with no alcohol-related diagnosis at baseline had a 7% incidence of dependence and a 4% incidence of abuse by the time of follow-up.

In another prospective study of the DSM-IV criteria, 435 highly educated men and matched comparison subjects who were participating in an ongoing investigation of sons of alcoholics were reassessed after a 5-year interval (

1,

10,

11). At the beginning of the 5-year period, when the subjects were approximately age 30, 63 men (14.5%) had ever fulfilled the criteria for alcohol dependence, 79 (18.2%) had ever met the criteria for alcohol abuse in the absence of dependence, and 293 (67.4%) had never demonstrated an alcohol use disorder. Structured personal follow-up interviews with the subjects and at least one additional informant revealed that 68% of those with alcohol dependence at the initial evaluation met at least one of the 11 DSM-IV alcohol abuse/dependence criteria at follow-up (thus fulfilling criteria for continued dependence), while 32% were free of these problems. Among the men with alcohol abuse at the initial evaluation, 36% maintained enough problems at the 5-year follow-up to be diagnosed with continuing abuse, 11% met the full DSM-IV criteria for alcohol dependence, and 53% met none of the DSM-IV alcohol abuse/dependence criteria. Finally, of the men who had satisfied no diagnostic criteria at the initial evaluation, 94% had no diagnosis at follow-up, but 1% had developed alcohol dependence and 5% had developed alcohol abuse. The study also evaluated characteristics at the initial evaluation that predicted meeting DSM-IV alcohol abuse/dependence criteria at 5-year follow-up in this white-collar, relatively highly functional group (

1). A higher risk for these problems was associated with the following characteristics at the initial evaluation: a history of consuming large quantities of alcohol, a history of a high frequency of alcohol consumption, meeting a higher number of the DSM-IV abuse/dependence criteria, reports of illicit drug use, evidence of less job stability, and a family history of alcohol dependence.

This study extends these earlier findings by reporting data from a follow-up at approximately 5 years in a large group of predominantly blue-collar men and women. The goal of these analyses was to evaluate whether the prognostic validity of the DSM-IV alcohol abuse/dependence criteria reported in previous studies could be replicated in a different group of subjects.

Method

The subjects gave written informed consent to take part in the phase II follow-up component of the Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcoholism. As described in more detail elsewhere (

12–

14), families were originally selected through a proband who met DSM-III-R and Feighner criteria for alcohol dependence and who entered treatment at any of six collaborating centers across the United States. The initial probands were invited to participate regardless of whether they had additional psychiatric diagnoses. Exclusion criteria were limited to the presence of an immediately life-threatening disorder, inability to speak English, or evidence of recent intense intravenous drug use.

All subjects and their available relatives were interviewed with the Semi-Structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism (

13), which is used to screen for 17 axis I DSM-III-R diagnoses and to gather detailed information about the clinical course of all substance use disorders. The interview also included questions relevant to DSM-IV substance use disorders. Information on family history was collected by using the Family History Assessment Module of the Semi-Structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism.

Identical methods were used to evaluate the comparison subjects selected at each of the six centers, along with their relatives. The comparison subjects were chosen through a variety of methods, including mailings to a random group of students and nonacademic staff at a university, to individuals listed in driver’s license records, and to individuals appearing for treatment in medical or dental clinics.

The phase II, follow-up component of the Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcoholism involved contacting initial probands, comparison subjects, and appropriate relatives an average of 5.1 years (SD=0.66) after the initial interview. Across the six centers, approximately 75% of eligible subjects agreed to participate in the follow-up (range=62%–81% across centers). The data reported are from subjects who were reinterviewed between November 1, 1996, and February 28, 1999. The follow-up face-to-face interviews were conducted with an updated version of the Semi-Structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism that included questions about the recency of psychiatric and substance use disorder symptoms, to determine whether they occurred during the follow-up period.

Alcohol-dependent subjects with antisocial personality disorder (7.5% of the original study group) were excluded from the analyses reported here in order to optimize comparisons with previous studies (

1,

8,

9). The 1,346 subjects were divided into groups of those with a lifetime history of DSM-IV alcohol dependence, a lifetime history of DSM-IV alcohol abuse, or no DSM-IV alcohol-related diagnosis at the time of initial interview (baseline). Then, subjects within each group were further divided into those who did and did not experience one or more of the 11 problems that constitute the DSM-IV alcohol abuse/dependence criteria during the 5-year follow-up period. Differences across groups were evaluated with the chi-square statistic for analysis of categorical data and with analysis of variance for continuous data. Finally, multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to determine the baseline characteristics that best predicted the pattern of DSM-IV alcohol abuse/dependence criteria experienced during the follow-up period.

Results

At follow-up, the 1,346 subjects had a mean age of 42.9 years (SD=13.7) and a mean of 13.4 years (SD=2.19) of education; 59.1% (N=795) were female. Approximately 17.7% (N=238) were probands in the Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcoholism, 54.0% (N=727) were relatives of probands, and 28.3% (N=381) were comparison subjects or members of their families. The racial distribution was 77.5% Caucasian (N=1,043), 12.3% African American (N=165), 7.4% Hispanic (N=99), and 2.9% other (N=39). At the time of follow-up, 62.5% of the subjects (N=841) were currently married, 20.7% (N=279) were single (never married), 14.9% (N=200) were separated or divorced, and 1.9% (N=26) were widowed.

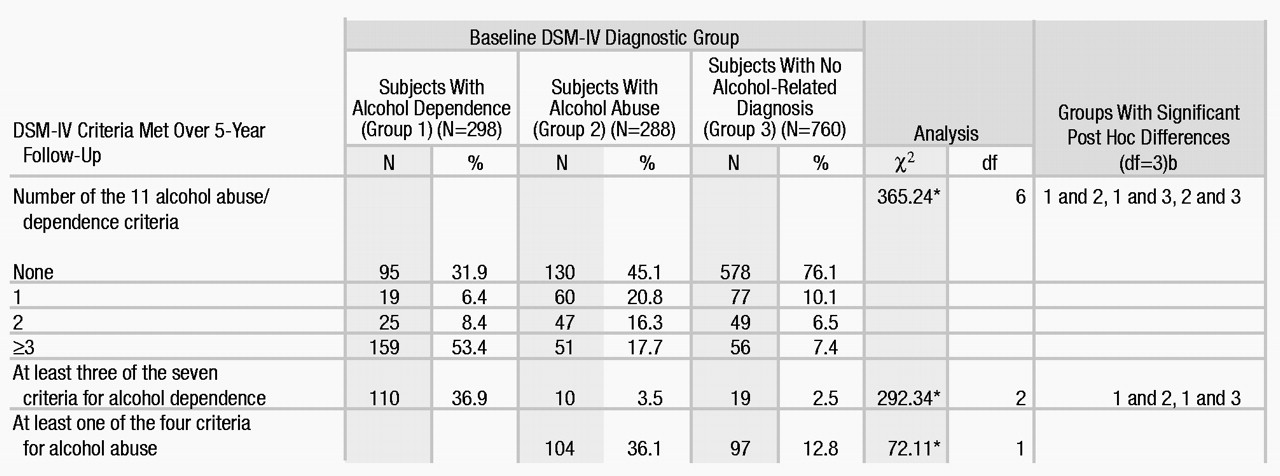

Table 1 shows the rate of occurrence of one or more of the 11 DSM-IV alcohol abuse/dependence criteria during the 5-year follow-up in the three groups of subjects categorized on the basis of alcohol-related diagnoses at baseline: those who had ever met criteria for alcohol dependence, those who met criteria for alcohol abuse in the absence of dependence, and those with no alcohol-related diagnosis. At follow-up, the proportion of subjects who met none of the criteria was highest in the group with no diagnosis, followed by the alcohol abuse group and the alcohol-dependent group, while the proportion of subjects with three or more problem areas was highest in the alcohol-dependent group, followed by the alcohol abuse group and the group with no diagnosis. The overall differences in the numbers of problems in the three groups was significant.

DSM-IV notes that a patient has continuing alcohol dependence if the patient experiences one or more of the 11 abuse/dependence criteria continuously over time. It is noteworthy that, in our study, more than half of the subjects with alcohol dependence at baseline met three or more of the 11 abuse/dependence criteria at follow-up and that nearly 37% of subjects with alcohol dependence at baseline met three or more of the seven criteria for alcohol dependence at follow-up. This latter rate was significantly higher than that observed for subjects with alcohol abuse or with no diagnosis at baseline. Only 3.5% of the men and women with alcohol abuse at baseline went on to develop alcohol dependence by the time of the follow-up, a rate not significantly higher than the 2.5% incidence of alcohol dependence at follow-up among the individuals with no initial diagnosis (Table 1). However, more than a third of the individuals with alcohol abuse at baseline met at least one of the four criteria of alcohol abuse at follow-up, compared with only about 13% of the individuals with no alcohol-related diagnosis at baseline, a significant difference (Table 1). Some of the individuals with alcohol abuse at baseline met one or two of the criteria for alcohol dependence at follow-up but did not meet enough criteria for a diagnosis of alcohol dependence.

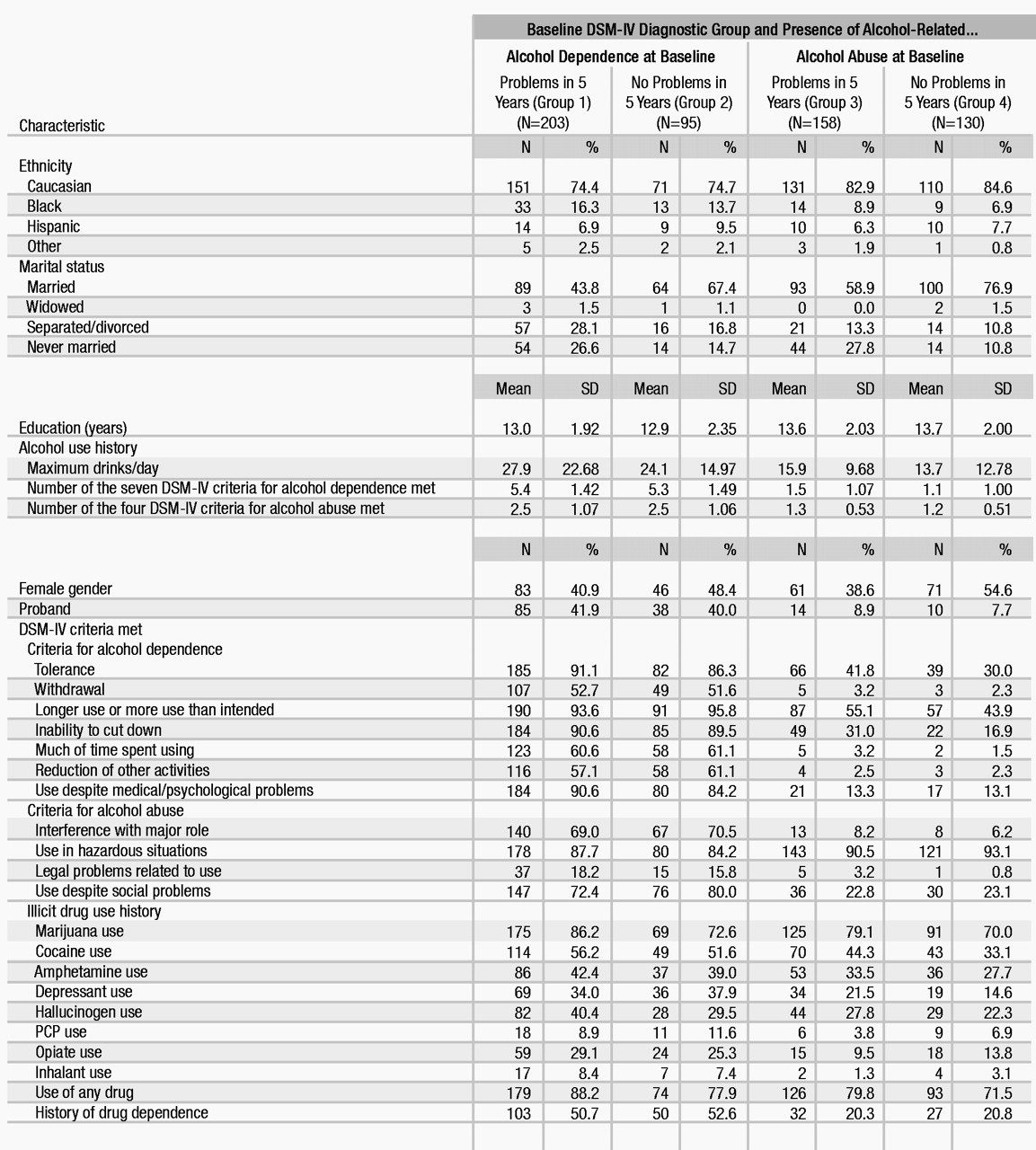

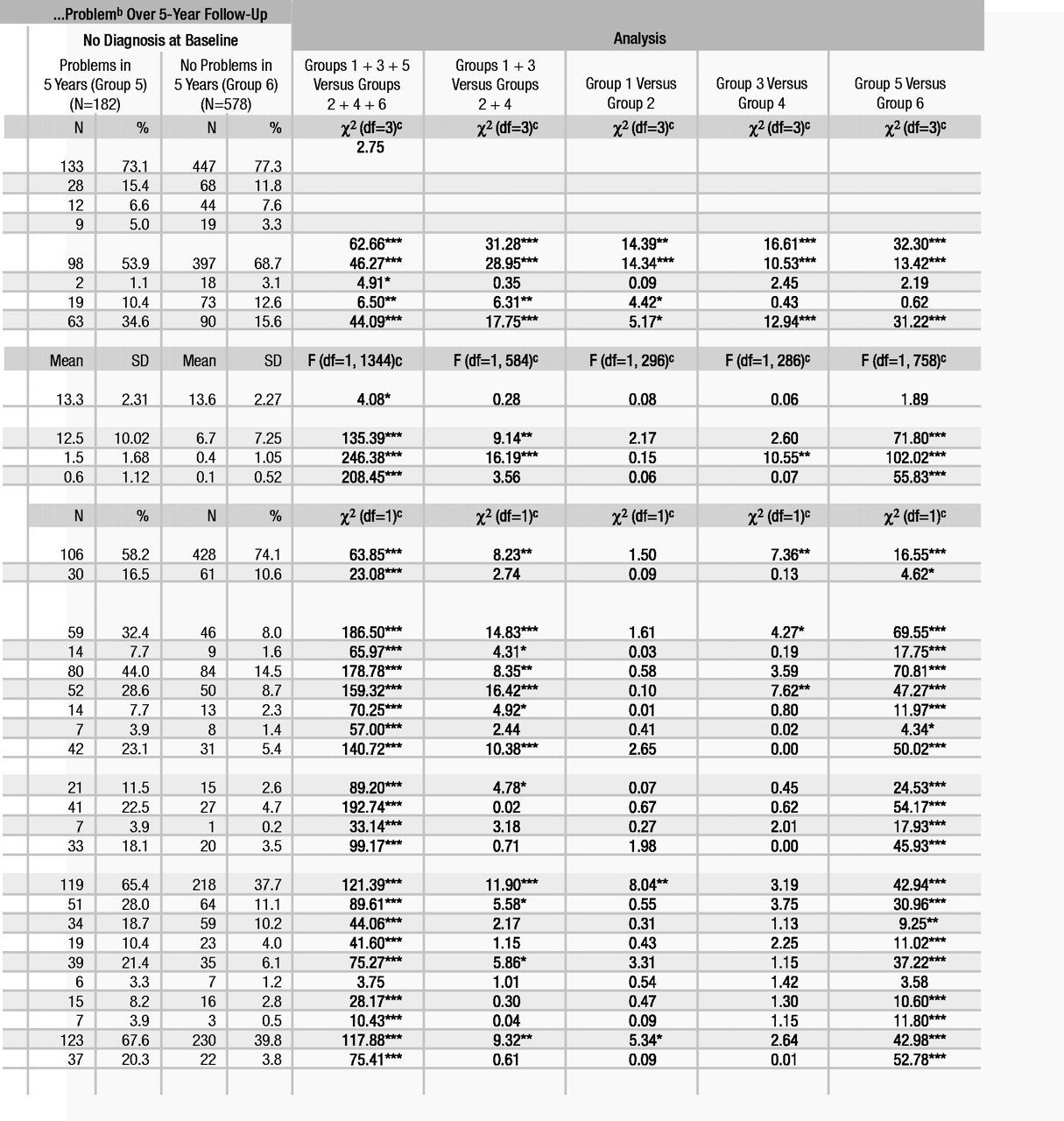

Table 2 presents data on the baseline characteristics that were associated with the occurrence during the 5-year follow-up of one or more of the 11 problems that constitute the DSM-IV alcohol abuse/dependence criteria. Data for individuals with dependence, abuse, or no diagnosis at baseline were analyzed separately. The overall statistical analyses included comparisons of the combined group of all individuals who reported having alcohol-related problems during the follow-up period (Table 2, groups 1, 3, and 5) and the combined group of those who did not (Table 2, groups 2, 4, and 6). When the difference between these combined groups was significant, comparisons were made between those with alcohol dependence or abuse at baseline who manifested alcohol-related problems during the follow-up and those who did not (Table 2, groups 1 and 3 versus groups 2 and 4). When appropriate, similar comparisons were made within the three diagnostic groups (Table 2, group 1 versus 2, group 3 versus 4, and group 5 versus 6). More men, probands, unmarried subjects, and people with less education developed alcohol problems during the follow-up, but there were no significant differences for race. The overall pattern of the data presented in Table 2 supported the contention that baseline univariate predictors of substance-related problems during follow-up also included a history of higher maximal alcohol intake and more alcohol-related problems. In addition, a history of use or abuse of drugs generally predicted alcohol-related problems, even in this study group, which excluded individuals with antisocial personality disorder. Data on these variables were evaluated across centers, with similar findings regarding gender, marital stability, baseline alcohol problems, and drug use as they related to alcohol problems at follow-up (data not shown).

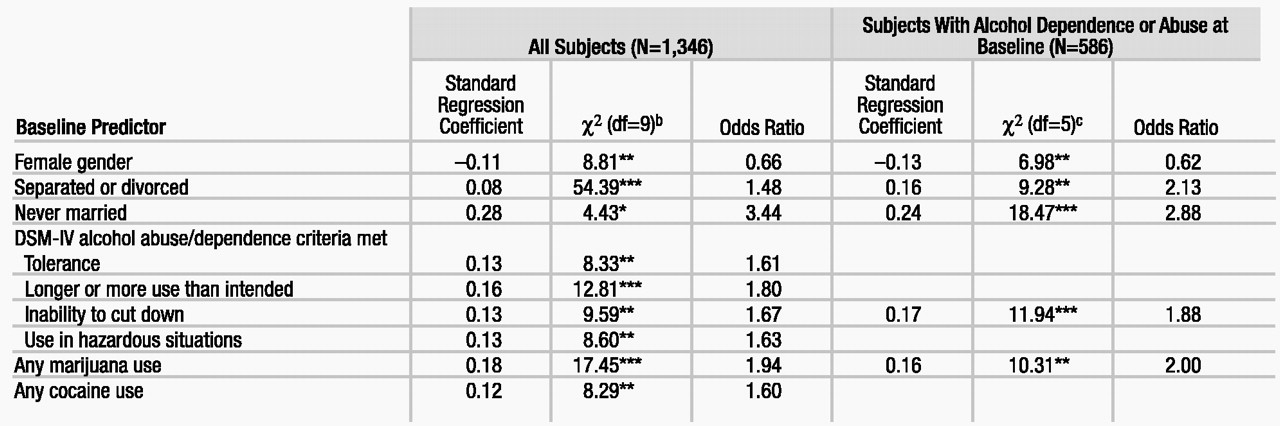

The evaluation of the characteristics associated with the 5-year rate of occurrence of one or more of the 11 DSM-IV abuse/dependence criteria as presented in Table 2 did not indicate which predictors continue to operate even in the context of the others. Therefore, all variables that significantly differentiated between the groups were entered into a logistic regression analysis, but two items (the number of dependence problems at baseline and reduction of other activities in order to use alcohol) significantly overlapped with other predictors and functioned as suppressor variables. With those two items removed, 30 variables were entered into the logistic regression analysis, with nine variables significantly contributing to a final equation (χ2=391.34, df=9, p<0.001) (Table 3). Consistent with the data reported in Table 2, the predictors included female gender (negative coefficient), lack of marital stability, three of the diagnostic criteria for alcohol dependence (tolerance, longer use or more use, inability to cut down), one diagnostic criterion for alcohol abuse (use in hazardous situations), and a history of marijuana or cocaine use. To evaluate the consistency of these general conclusions across centers, the regression analysis was repeated while adding dummy coded variables for the six centers. The results for the items presented in Table 3 were unchanged. When the full set of predictors was subsequently applied to the subgroup of subjects who had evidence of alcohol abuse or dependence at baseline, the same types of items entered the equation, although only five items contributed significantly (χ2=61.50, df=5, p<0.001).

Discussion

These data support the usefulness of DSM-IV diagnoses of alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence as predictors of the clinical course over the subsequent 5 years after diagnosis. Both diagnoses were associated with an increased risk for experiencing one or more of the 11 DSM-IV alcohol abuse/dependence criteria over a 5-year period, compared to the risk for individuals who had no history of an alcohol use disorder.

The results also support the conclusion that abuse is not just a prodromal phase of dependence, at least not over a 5-year period. Although about half of the men and women with alcohol abuse at baseline continued to have some alcohol-related problem at follow-up, only 3.5% went on to develop dependence, a rate that was not significantly different from the 2.5% incidence of dependence among subjects who had no diagnosis at baseline.

These two conclusions are consistent with several longitudinal evaluations of the prognostic implications of alcohol abuse and dependence. Both a 1-year follow-up of a general population sample from New Jersey and a 5-year follow-up of relatively highly educated and functional sons of alcoholics and comparison subjects also indicated that about two-thirds of individuals with dependence continued to have DSM-IV substance-related problems (

1,

9). Furthermore, the current study agrees with the two earlier studies that at least a third of those with alcohol abuse maintain that diagnosis at follow-up, while a substantial proportion demonstrate no problems. The two prior studies reported that the 1–5-year probability of the de novo development of abuse in adult populations is between 3% and 5%, while the rate in the current study was close to 13%. This difference may be related to the lower educational level and high familial loading for alcohol problems among subjects in the Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcoholism. All three investigations reported rates of 7% or less for new cases of alcohol dependence.

There is additional support for the probable independence of alcohol abuse and dependence. Prior factor or cluster analyses of the 11 DSM alcohol abuse/dependence criteria reveal the existence of two separate factors relating to alcoholism, one that is consistent with the criteria for abuse and one that is consistent with those for dependence (

5–

7,

15–

18), although not all studies agree (

19,

20). Evidence supporting the distinction between alcohol abuse and dependence also comes from the documentation of differences in cross-sectional clinical characteristics, such as quantity of alcohol consumed and treatment histories, between people with the two disorders (

6,

9,

21,

22). However, these differences are not as strong as those between subjects with abuse or dependence and subjects with no diagnosis.

The proportion of subjects with abuse or dependence who reported none of the 11 alcohol-related problems at follow-up is worth noting. Almost one-third of the alcohol-dependent men and women and almost half of those with alcohol abuse reported no difficulties. These results are likely to reflect the 20% or higher spontaneous remission rate in alcohol dependence, the fluctuating nature of alcohol problems over the lifetime, and the effects of interventions and treatment (

23–

25). Although the follow-up interviews were not structured to allow conclusions about cause-and-effect for those events, the data highlight the substantial proportion of people with alcohol abuse and dependence who do well (

1,

9).

The current study also identified characteristics that predict the occurrence of problems within diagnostic categories. Consistent with the findings for the highly functioning group of sons of alcoholics and comparison subjects (

1), specific predictors included marital status (never married), the presence of several dependence criteria, and evidence of the use of illicit substances. The results in the 1-year follow-up of a general population sample in New Jersey (

9) were consistent with our finding that prior substance-related problems predict outcome, but the earlier evaluation demonstrated an additional impact of race (Caucasian) that was not corroborated here.

In interpreting the current data, it is important to consider that only the abuse/dependence criteria for alcohol were evaluated and that only the properties of DSM-IV were studied, without comparisons to other diagnostic schemes. Additional investigations will be needed to determine the prognostic meaning of other DSM-IV substance use disorders. Furthermore, the subjects were participants in the Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcoholism, an investigation involving families with a high density of alcoholics. Thus, the rates of alcohol abuse and dependence might have been inflated by the high familial loading for these disorders. Factors predictive of problems might differ across groups with different levels of education or other differences in background characteristics. In addition, all information about the rate of problems during the follow-up came from self-reports. Finally, although the 75% rate of participation in the follow-up is substantial, the results might have been different if all the eligible subjects had been evaluated at follow-up. However, taken together with the findings of two prior prospective studies, the current results support the usefulness of the DSM-IV criteria for alcohol abuse and dependence.