Over the last three decades, compelling evidence has accrued indicating that adverse experiences early in life, such as childhood abuse and neglect as well as parental loss, result in a greater than usual risk for the development of mood and anxiety disorders in adulthood, including major depressive disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (

1–

6). This higher stress vulnerability may be mediated by persistent alterations in neurobiological systems that are known to be stress-responsive. Central nervous system (CNS) corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) systems are likely involved in mediating the effects of stress early in life on the development of certain psychiatric disorders in adulthood. First, the heterogeneous distribution of CRF neurons in cortical, limbic, and brainstem regions infers a role for CRF as a major regulator of the endocrine, autonomic, immune, and behavioral stress responses (

7). Second, direct CNS application of CRF to laboratory animals produces many physiological and behavioral changes that parallel the cardinal symptoms of depression and anxiety (

8). Third, higher than normal CRF concentrations have repeatedly been measured in the CSF of patients with major depressive disorder and PTSD (

9–

11). Fourth, findings from preclinical laboratory animal studies have provided evidence that stress early in life, i.e., maternal separation in rats or adverse rearing conditions in nonhuman primates, produces long-lived hyperactivity of CRF neuronal systems as well as greater reactivity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis to stress in adulthood (

11–

14). The concatenation of these findings suggests that genetic vulnerability coupled with early stress in a critical and plastic period of development may result in persistent sensitization of CRF neuronal systems to even mild stressors in adulthood, forming the basis for the development of mood and anxiety disorders (

15). In support of this hypothesis, we recently observed higher pituitary-adrenal and autonomic responses to a standardized psychosocial laboratory stressor in adult women with a history of childhood sexual and/or physical abuse (

16). Sensitization of the stress response was particularly robust in abused women with symptoms of depression and anxiety, including PTSD symptoms.

To further explore the mechanisms of this biological vulnerability to stress in these women, we employed standard HPA axis challenge tests, including the CRF stimulation test and ACTH1–24 stimulation test. The administration of synthetic CRF stimulates ACTH release from the pituitary corticotrophs and, subsequently, cortisol release from the adrenal cortex. Thus, the CRF stimulation test allows an evaluation of the reactivity of the adenohypophysis to CRF. In contrast, a psychosocial stress test stimulates a stress response involving higher levels of cognitive and emotional processing mediated by several neurotransmitter systems. Changes in pituitary responsiveness to CRF stimulation may reflect CRF receptor changes on corticotrophs due to alterations in the activity of the paraventricular nucleus/median eminence CRF circuit. Similarly, the administration of high doses of biologically active ACTH1–24 allows for the evaluation of the maximal response capacity of the adrenal cortex.

Results

Description of the study groups

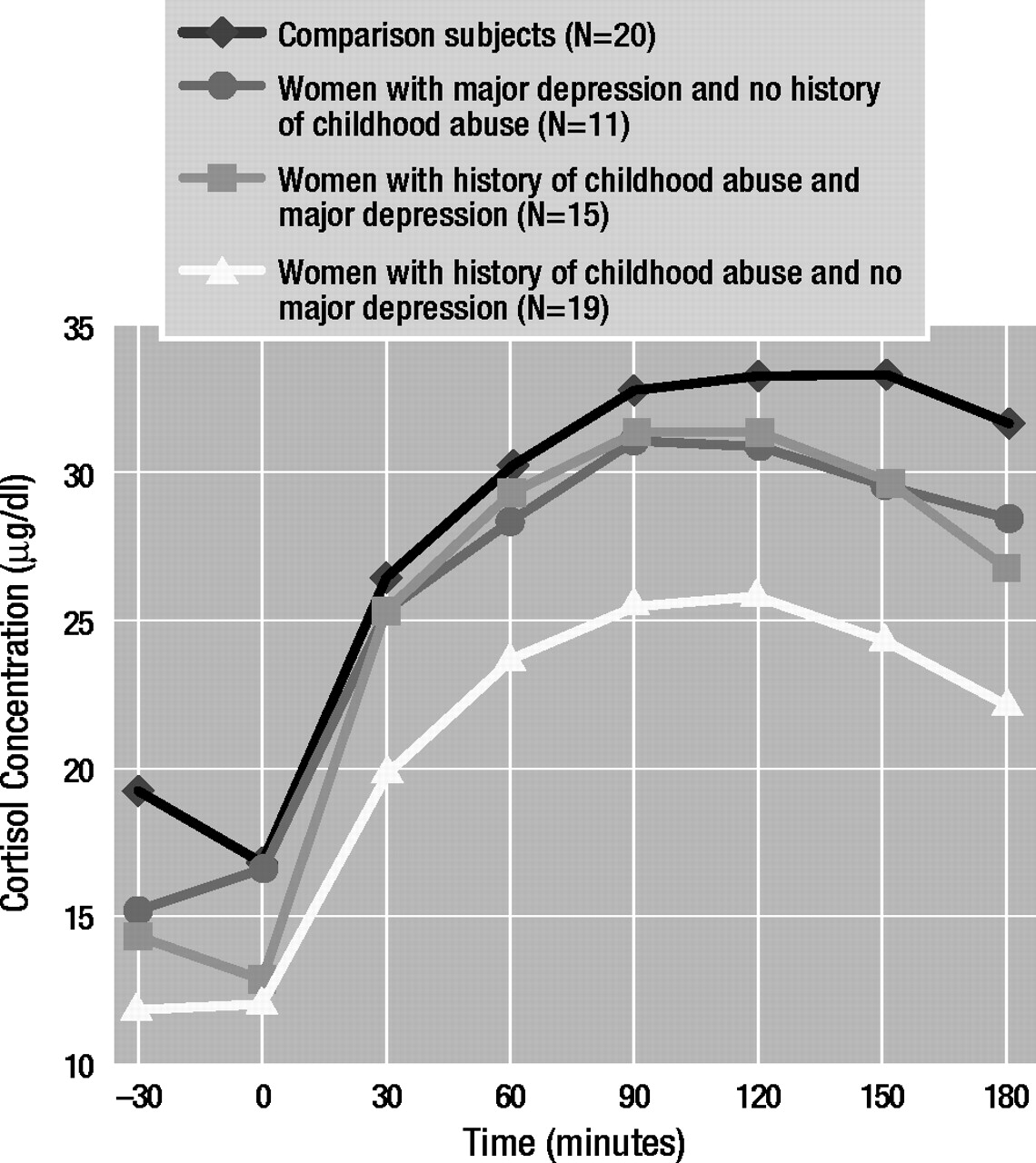

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the study groups. There were significant differences in groups with respect to age and racial distribution but not with respect to education. As expected, abused women attained higher numbers and magnitude scores on the Early Trauma Inventory than nonabused women. Depressed women had significantly higher mean Hamilton Depression Rating Scale scores than nondepressed women. Although it was perhaps not clinically significant, mean Hamilton depression scale scores were statistically higher in abused women without major depressive disorder than in comparison subjects. It is of interest that there was a significantly higher prevalence of PTSD in the group of abused women with current major depressive disorder than in the abused women without major depressive disorder. A history of childhood abuse as well as current major depressive disorder was associated with higher numbers of negative life events in the past year. Depressed women reported more intense daily hassles in the past month than nondepressed women. Abused women with major depressive disorder attained a significantly higher mean negative life events score (t=3.12, df=17.68, p<0.01) and Daily Hassles Scale score (t=3.09, df=30, p<0.01) than abused women without major depressive disorder.

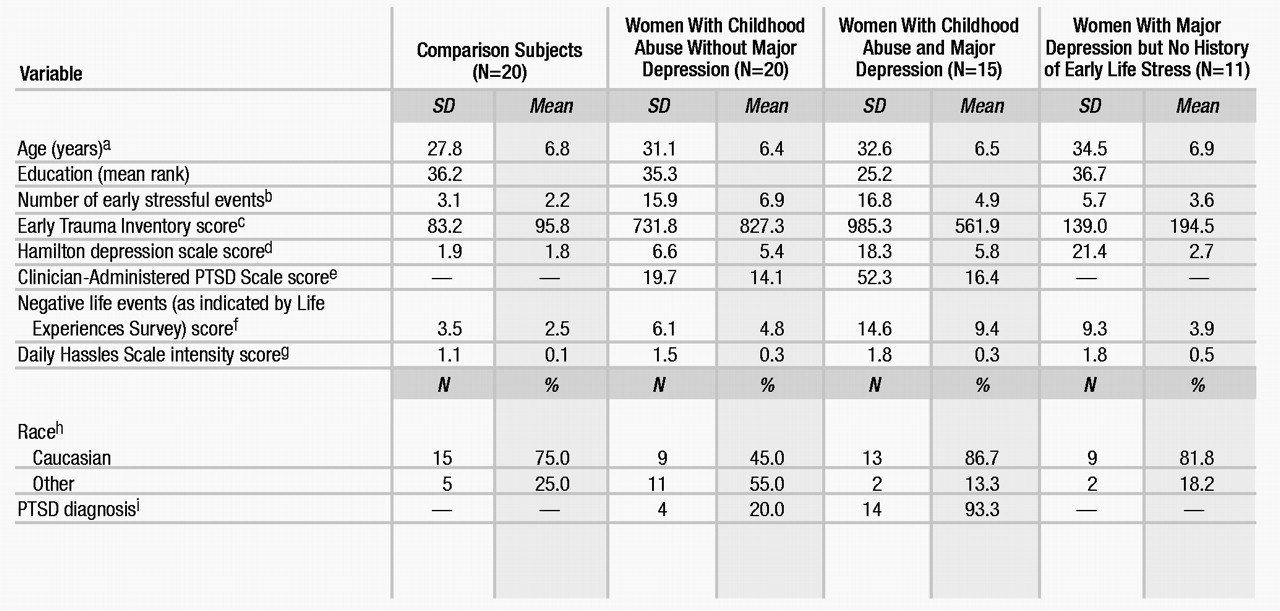

CRF stimulation test

Three-way analysis of covariance with repeated measurement revealed two significant main effects (time: F=2.68, df=11, 649, p<0.01; major depressive disorder: F=21.76, df=1, 59, p<0.01), a significant two-way interaction effect (time by major depressive disorder: F=5.61, df=11, 649, p<0.01), as well as a significant three-way interaction effect (early life stress by major depressive disorder by time: F=1.87, df=11, 649, p<0.05). Education and race had significant effects on mean ACTH concentrations (education: F=6.24, df=1, 59, p<0.05; race: F=8.02, df=1, 59, p<0.01) and response profiles (education by time: F=3.72, df=11, 649, p<0.01; race by time: F=4.83, df=11, 649, p<0.01). Dunn’s multiple comparison procedure (critical values: tD[0.05/2; 36,649]=3.23; tD[0.01/2; 36,649]=3.66) revealed that abused women without major depressive disorder demonstrated higher mean stimulated ACTH concentrations than comparison subjects at 5 (tD=5.08), 15 (tD=7.16), and 30 minutes (tD=6.79). Abused women with major depressive disorder (60 minutes: tD=3.34, 120 minutes: tD=3.42) and depressed women without a history of abuse (60 minutes: tD=3.26) exhibited lower stimulated ACTH concentrations than comparison subjects (Figure 1).

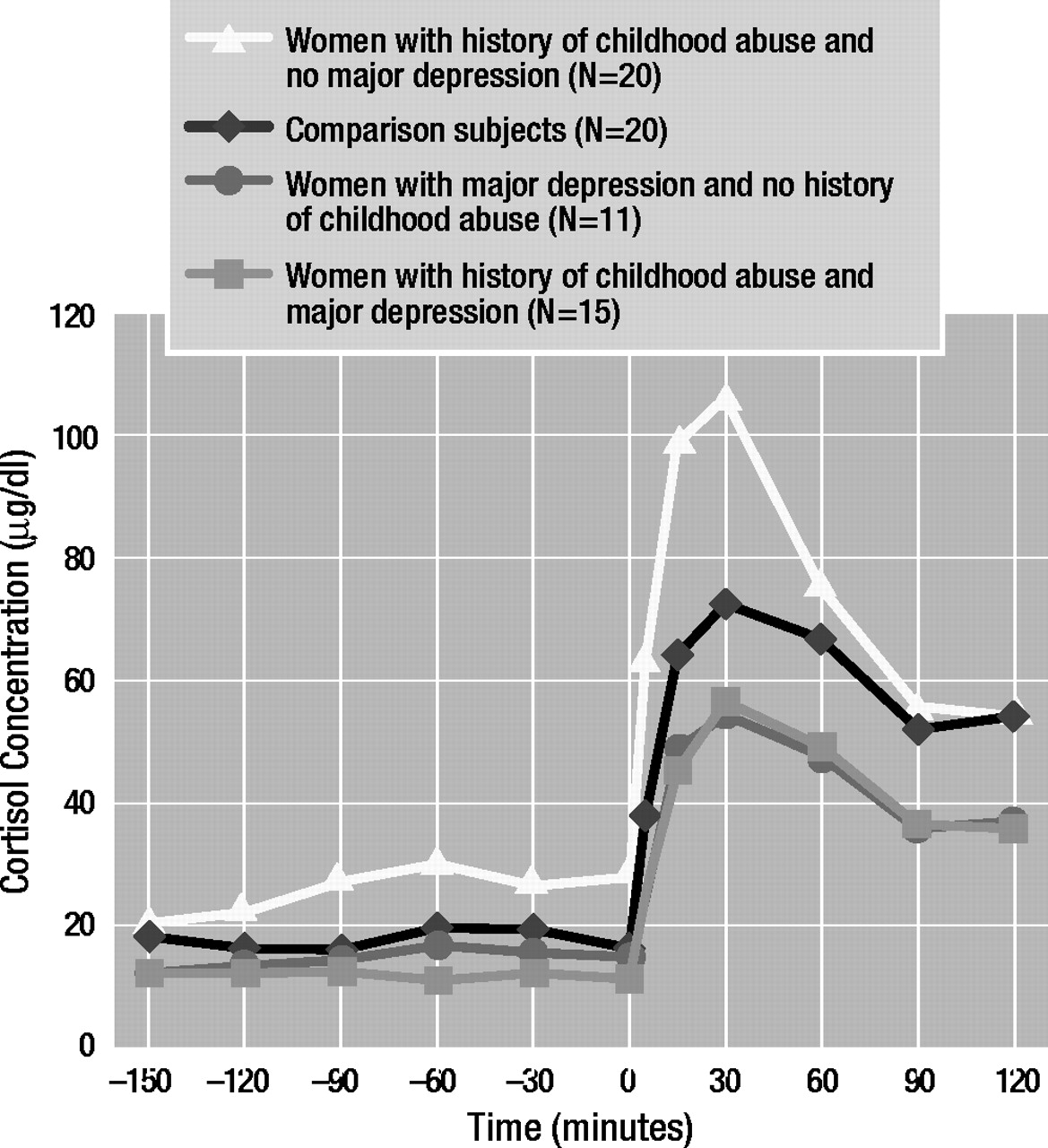

As for cortisol concentrations in the CRF stimulation test (Figure 2), three-way analysis of covariance with repeated measures revealed a significant main effect of time (F=7.86, df=11, 649, p<0.01) as well as a significant three-way interaction effect (early life stress by major depressive disorder by time: F=4.43, df=11, 649, p<0.01). Dunn’s multiple comparison procedure (critical values: tD[0.05/2; 36,649]=3.23; tD[0.01/2; 36,649]=3.66) showed that abused women with major depressive disorder demonstrated lower baseline and stimulated cortisol levels than comparison subjects at –150 (tD=4.12), –90 (tD=3.83), –60 (tD=4.29), –30 (tD=4.55), 0 (tD=4.01), 5 (tD=4.05), 90 (tD=4.07), and 120 (tD=4.96) minutes. Abused women without major depressive disorder also demonstrated lower basal and stimulated cortisol concentrations at –150 (tD=5.51), –120 (tD=4.84), –90 (tD=3.82), 90 (tD=5.96), and 120 (tD=8.29) minutes.

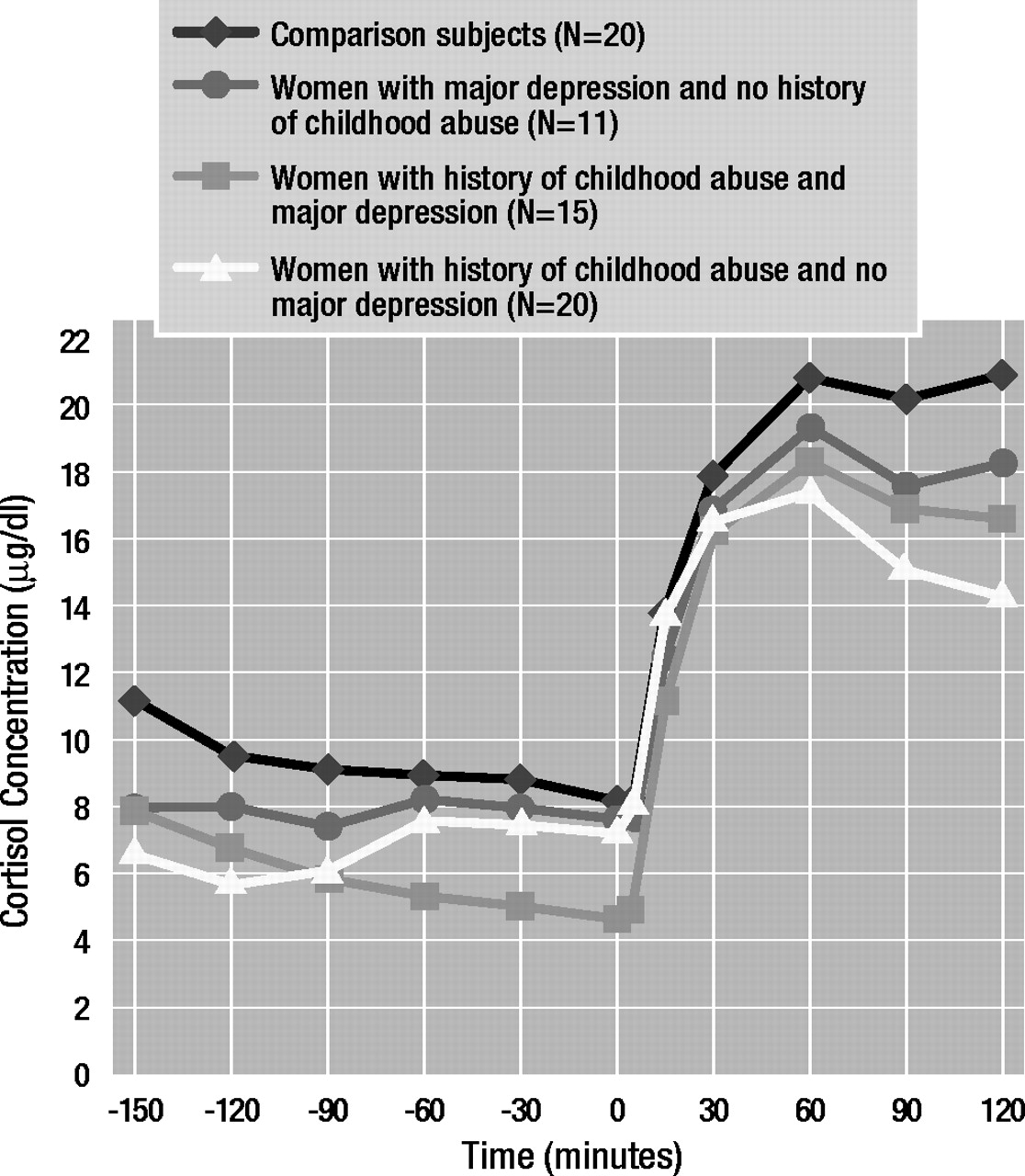

ACTH1–24 stimulation test

Results obtained by using three-way analysis of covariance with repeated measures (Figure 3) revealed a significant main effect of time (F=5.15, df=7, 406, p<0.01) and a significant three-way interaction effect (early life stress by major depressive disorder by time: F=2.18, df=7, 406, p<0.05). Education had a significant main effect on cortisol concentrations (F=4.33, df=1, 58, p<0.05). Dunn’s multiple comparison procedure (critical values: tD[0.05/2; 24,406]=3.02; tD[0.01/2; 24,406]=3.48) revealed that abused women who were not depressed exhibited lower basal and stimulated cortisol concentrations at –30 (tD=6.83), 0 (tD=4.38), 30 (tD=5.92), 60 (tD=6.01), 90 (tD=7.35), 120 (tD=7.43), 150 (tD=8.24), and 180 (tD=8.96) minutes than comparison subjects. Abused women with depression also showed lower basal cortisol levels at –30 (tD=4.14) and 0 (tD=3.37) minutes than comparison subjects.

Discussion

It is now well established that early adverse experiences constitute a major risk factor for the development of major depressive disorder and certain anxiety disorders, including PTSD. In adulthood, symptoms of depression and anxiety as well as posttraumatic stress symptoms often exacerbate in relationship to acute or chronic life stress (

29,

30). We have, thus, hypothesized that stress early in development may alter the set point of the stress response system, rendering these individuals particularly vulnerable to stress and increasing their risk for stress-related diseases. This stress vulnerability may be mediated through persistent hyperactivity and/or sensitization of CNS CRF systems. In support of this hypothesis, we recently demonstrated a marked increase in pituitary-adrenal and autonomic reactivity to psychosocial laboratory stress in adult women with a personal history of childhood sexual or physical abuse (

16). We now present findings on pituitary-adrenal reactivity to standard endocrine provocative tests in these women. Adult women with a history of childhood abuse without major depressive disorder exhibit an exaggerated ACTH response to exogenous CRF. In women with a history of childhood abuse with major depressive disorder, the ACTH response is blunted and resembles that of depressed women without a history of childhood adversities. There also appears to be an altered adrenocortical function in abused women without depression, reflecting adrenocortical insufficiency. Although the two groups of abused women did not differ with respect to the magnitude of childhood abuse, abused women with current major depressive disorder suffered more often from comorbid PTSD and reported more recent chronic mild stress than abused women without major depressive disorder.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first clinical study of pituitary-adrenal responses to CRF and ACTH

1–24 administration in adult survivors of childhood abuse. However, several studies have been published in which the CRF stimulation test was administered to abused children (

31,

32). DeBellis et al. (

31) reported that sexually abused girls exhibit a blunted ACTH and normal cortisol response in a standard CRF stimulation test. These findings are comparable to our findings in abused women with current major depressive disorder. The majority of the abused girls studied by DeBellis et al. suffered from dysthymia; unfortunately, PTSD was not systematically evaluated, and the abused girls were not subgrouped according to the presence or absence of psychiatric disorders. More recently, Kaufman et al. (

32) reported that abused children with major depressive disorder demonstrate enhanced ACTH responses and normal cortisol responses when living under conditions of ongoing abuse. These subjects were also at high risk for comorbid PTSD. Taken together with our findings, one might posit that an initial sensitization of the stress response system evolves into a blunted pituitary responsiveness over time in the face of ongoing stress.

Several studies have measured pituitary-adrenal axis responses to CRF in patients with major depressive disorder or anxiety disorders, including combat-related PTSD. In general, blunted ACTH and normal cortisol responses have been reported (

33–

35). We further extend these findings by demonstrating a similar blunting of the ACTH response in abused women with current major depressive disorder and comorbid PTSD. In contrast, we did not observe basal hypercortisolemia or higher cortisol responses to ACTH

1–24 (

24,

36) in our group of depressed women without a history of childhood abuse. It is unlikely that the latter finding is caused by ceiling effects, since other authors have reported considerably higher ACTH

1–24-stimulated cortisol concentrations in depressed subjects, whereas those of comparison subjects were comparable to those in our study (

24). Abused women, with and without depression, demonstrated low basal adrenocortical activity. Furthermore, abused women without major depressive disorder also exhibited decreased plasma cortisol concentrations after administration of ACTH

1–24. Lower basal adrenocortical activity is a prominent finding in patients with PTSD in the aftermath of other trauma experiences, such as combat exposure, Holocaust victimization, or earthquakes (

37). However, the capacity of the adrenal gland to respond to ACTH has never been studied in patients with PTSD (

38).

Animal models of early untoward stressful life events, e.g., maternal separation, have provided evidence for higher CNS CRF activity and higher ACTH responses to acute psychological stress in adulthood (

12,

13). These findings are in accordance with our recent findings of higher pituitary reactivity to psychosocial stress in adult women with a history of childhood abuse (

16). Unfortunately, comprehensive endocrine challenge studies in animal models of early abuse and depression have not been performed. This is of paramount importance because a stress exposure and a CRF stimulation test address different levels of the HPA axis; therefore, findings are not directly comparable. As shown by our findings, indeed, pituitary responses can be enhanced in response to a laboratory stressor and blunted in response to exogenous CRF stimulation. Most likely, CRF receptors are down-regulated because of chronic CRF hypersecretion from the hypothalamus in the face of greater exposure to recent stress in abused women with major depressive disorder. Indeed, reduction of pituitary CRF receptor numbers has been observed in adult rats who were maternally deprived in the postnatal period, despite an exaggerated ACTH response to stress (

13). Thus, greater pituitary responses to acute stress may involve activation of corticolimbic pathways, resulting in higher endogenous CRF activation and/or other neuromodulators such as arginine vasopressin. Recent studies (

39) have indicated that maternal separation also increases CRF neuronal activity in corticolimbic pathways and in the locus ceruleus, both of which have long been implicated in the pathogenesis of depression and anxiety (

15). It is of interest that during chronic stress or after a single stress exposure, a shift in the ratio between hypothalamic arginine vasopressin and CRF expression occurs, resulting in greater arginine vasopressin-releasing activity as well as sensitization of pituitary arginine vasopressin receptors (

40,

41). Such mechanisms may underlie the HPA axis dysfunction in adult survivors of childhood abuse and require further scrutiny.

Mechanisms of adrenocortical counterregulation are obscure. In some animal models of severe stress early in life, dissociation of central and adrenocortical (re)activity was noted (

13,

14). In our study (

13), rats who were maternally deprived for 6 hours/day during the postnatal phase exhibited greater CNS CRF activity and greater basal and stress-induced ACTH concentrations along with unaltered basal and stress-induced corticosterone concentrations. Remarkably, we (

14) found higher CSF CRF concentrations and lower CSF cortisol concentrations in nonhuman primates exposed to early adverse rearing conditions. Thus, there appears to be peripheral adaptation to CNS hyperactivity as a result of early stress. Similar findings have been obtained in patients with fibromyalgia and other related disorders known to be related to early life stress, trauma, and PTSD (

38). Thus, first, alterations at the adrenal level may contribute to hypocortisolism in PTSD, and, second, a lack of the protective effects of cortisol may increase the risk for the development of immune-related disorders (

38).

Taken together, we conclude that severe stress early in life is related to greater sensitivity of the HPA axis to stress in adulthood, which underlies greater vulnerability to major depression. Stress early in life may initially lead to sensitization of the anterior pituitary to CRF, possibly reflecting a biological vulnerability to the effects of stress. This vulnerability may result in relatively high CRF secretion whenever these women are stressed, which may eventually lead to pituitary receptor down-regulation and to depression and anxiety because of the behavioral effects of CRF at extrahypothalamic sites. Relative adrenal insufficiency may increase these women’s risk for the development of immune-related disorders or pain syndromes. A lack of feedback may additionally drive central CRF release and symptoms of stress, depression, and anxiety. The seeming discrepancy between greater ACTH responses to psychosocial stress and blunted ACTH responses to CRF stimulation in abused women with major depression may reflect the involvement of corticolimbic pathways and enhanced hypothalamic releasing activity (CRF and other releasing factors), thus overriding receptor down-regulation.

Future studies should explore indices of extrahypothalamic CRF activity and other releasing factor activity, as well as mechanisms of adrenal dysfunction in adult survivors of childhood abuse. Finally, it should be determined whether this biological alteration, which may represent a risk factor for stress-related disorders, can be reversed by either pharmacological or psychological treatment in different stages of its development.