As more individuals with serious mental illness reside in the community, mental health agencies offer employment, family, and community support services that situate service providers within the client’s natural environment. Case managers and other staff may provide the primary day-to-day links between clients and their families, neighbors, and employers, a process some have called “synthetic social support” (

1). For severely disabled clients these treatment relationships may continue indefinitely. However, regular involvement by a case manager in a client’s social, family, vocational, or leisure life over an extended period may blur the distinction between a treatment relationship and a casual friendship, creating role confusion, loss of objectivity, and other interpersonal boundary problems (

2–

4).

Compounding these risks, case managers and other entry-level staff are not selected for the amount and type of their formal education but instead for qualities like comfort in interacting with people who have serious mental illness and the ability to think and work independently (

5). Many are young or lack a postgraduate professional education (

6). Even providers with adequate education, training, and experience encounter ethical dilemmas that put two or more values in conflict (

7), such that they sometimes rely on personal values and practical considerations more than on ethics codes when deciding what to do (

8,

9). Furthermore, although services are increasingly expected to be “consumer driven,” with meaningful client participation in decisions, clients and providers can differ in their values and beliefs (

10). Value issues may grow in significance as current or former clients assume case manager and other provider roles (

11–

13).

As changes in the nature and format of services raise new ethical concerns (

7,

14–

16), we have little empirical data on ethical choices made by community-based providers. McGrew and colleagues (

17) surveyed members of 121 assertive community treatment teams, focusing in part on their experience and management of relationship boundary issues and other ethical dilemmas. Respondents perceived some boundary problems as frequent but not usually serious (for example, a needy client asking for a small loan), and others as infrequent but potentially very serious (for example, romantic attraction to a client).

Boundary issues affect everyday practice in all settings (

2–

4,

18) but may operate differently in rural mental health care (

19–

21). Overlapping relationships can be inevitable in rural communities, where participation of all residents in multiple aspects of community life, such as in school and in church, is not only normal but expected (

21,

22). Established relationships can promote trust and give rural providers a more comprehensive understanding of clients’ needs, as well as opportunities to role model prosocial interactions in settings unrelated to treatment. Furthermore, because many rural communities have few trained providers, a provider’s conservative ethical decision not to serve a client because of a preexisting relationship might mean that the client would receive no services.

Providing synthetic support to clients thus complicates interpersonal boundaries, especially in rural communities. We know little about how providers deal with these ethical gray areas, some of which arise unexpectedly and require an immediate decision. Situations in which breaking client confidentiality for a compelling although not a legally permissible reason can also arise frequently; however, such situations are no more likely to occur in rural communities than in nonrural communities. Because ethical decisions can reflect factors other than formal ethical principles, research should also examine the reasons used to justify decisions.

The purpose of this study was to examine the decisions made and ethical justifications used by rural and nonrural mental health providers in response to hypothetical ethical dilemmas concerning boundaries or confidentiality. We hypothesized that rural providers would make fewer conservative decisions in response to boundary dilemmas than those working in nonrural settings, but that the rural providers would not differ in decisions about confidentiality dilemmas. Although not central to our focus, we also examined the relationships between providers’ ethical decisions and justifications and their background characteristics and previous ethics training, as well as clients’ sex.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 95 community-based mental health staff at eight sites operated by five mental health centers in a Midwestern state. The centers were dispersed geographically across this state. Two agencies served urban communities, one served a medium-sized city, and three served rural communities. One of the rural agencies also served urban clients at a different office. Sixty-three participants (66 percent) were women, and 31 were men. (One participant did not answer the question.) Seventy-nine (83 percent) were European American, and 16 (17 percent) were African American or of other ethnic backgrounds.

Their mean age was 36.9 years (range, 19 to 66 years), and the mean number of years of their overall experience as mental health providers was 7.3 (range, one to 25 years). Ten participants (10.5 percent) had completed high school or had some college, 40 (42 percent) had an associate or bachelor’s degree, and 45 (47 percent) had postgraduate course work or degrees. Twenty-two (23 percent) identified social work as their college major, 35 (37 percent) psychology, and seven nursing, and 31 cited miscellaneous other disciplines such as business or sociology.

Fifty-nine participants (62 percent) said their jobs had provided some formal training in ethics, while 35 (37 percent) said their jobs had not. (One participant did not answer the question.) Sixty-eight (72 percent) worked in urban or suburban settings, and 27 worked in rural areas. Twenty-three participants (24 percent) were entry-level direct-care providers, such as group home staff, 28 (29 percent) were case managers, eight were nurses, and 35 were supervisors.

Materials

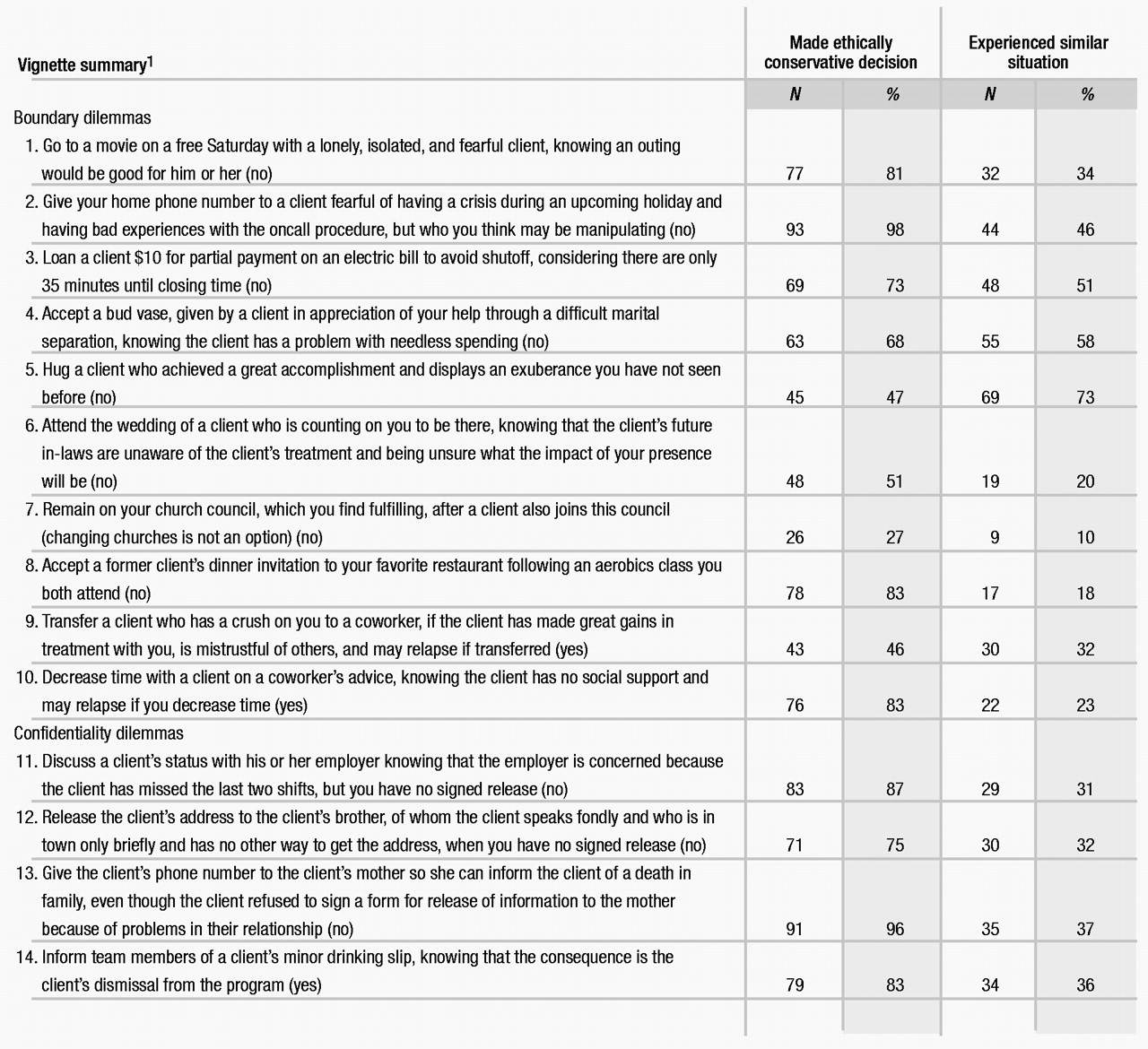

Using sources in the literature (

2,

7,

8), we created 14 vignettes describing hypothetical dilemmas involving professional role boundaries or client confidentiality and privacy. The vignettes are summarized in Table 1, and one is presented in full below. Participants were asked to make a yes-no decision about taking a specified course of action in response to each dilemma. As indicated in Table 1, less conservative decisions were viewed as those permitting an extratherapeutic basis for client-provider relationships or the handling of privileged information. Providers justified their yes-no decision, noted whether it would make a difference how long they had worked with the client in question, and indicated if they had ever had an experience like that described in the vignette. If they had, they were asked how they had handled the dilemma.

The 14 vignettes averaged 192 words in length (range, 94 to 326 words) and were prepared and revised as necessary to make either a yes or a no decision ethically justifiable. Vignettes were presented to participants in random order. Half the time in each vignette the client was identified as male, and the rest of the time as female; thus each respondent received randomly ordered vignettes for seven males and seven females.

Sample vignette. “One of your clients is getting married. She is very excited and states that she would be honored if you could come to the wedding. The wedding is very important to her. She had to resolve many problems within herself and in her relationships before she was able to make this step. She has often stated that you helped her make it to this stage in her life and feels you should attend the event. She has mentioned that it will be a small wedding with only family attending. Although her family knows she is in treatment, the client has stated that the groom’s family does not. You feel that the client does not fully understand the implications of your attending the wedding. You are unable to contact the client before the event to discuss your concerns with her. She leaves a message saying how much it means to her that you will be there. You feel that not going will cause a setback in her treatment. Do you attend the client’s wedding?”

Procedure

After obtaining institutional review board approval for the study, the investigators approached the chief administrative officer, clinical services director, or other appropriate senior staff person at each mental health center for cooperation in soliciting staff participation in the survey. Every administrator approached was cooperative and put the investigators in touch with the appropriate department heads. Each department head provided time at one or more staff meetings for the investigators to describe the study and solicit participants. Participation was voluntary and entailed a full informed consent process.

At six of the eight sites, all staff who were approached agreed to participate and completed the survey. Because the other two sites were larger and not all staff could be present when the study was described, extra surveys and consent forms were left for these staff. At one of these sites, 20 of 30 eligible staff returned completed surveys, and at the other site ten of 20 did so. In total, the 95 staff who completed surveys represented 83 percent of the 115 invited to participate. Participants completed the survey individually and anonymously, and their agencies were not identified on the surveys. Participation took 40 to 60 minutes depending on how detailed the respondent’s answers were. As a token of appreciation, after completing the survey each participant received his or her choice of a $5 gift certificate for discount stores, video rental, or fast food.

Although all participating agencies addressed issues of confidentiality and formal role relationships in staff orientation and training, they varied in the amount of written documentation provided to staff on these matters. No agency had any written documentation specific to the gray areas under study here.

Ethical justification

Open-ended items asking participants for justification for their decisions were coded into six categories: formal policy, personal policy, consumer-therapeutic, propose alternative, consult team-supervisor, and other-missing. This coding was independent of any other information provided, such as whether the respondent had made a yes or a no decision. Sometimes respondents provided relevant information concerning how they had handled a similar situation in the past, and when appropriate, this information was used to help code ambiguous or incomplete justifications.

Justifications coded as formal policy (45 percent of the total) included responses that seemed to be based on specific formal policies, such as agency prohibition (for example, “My agency does not allow me to accept gifts from clients”), generic statements of principle (“It’s wrong,” or “It’s unethical”), formal ethical principles (“Because of confidentiality,” or “Because of dual roles”), vague reference to principles (“Because of boundary issues”), and various rules of thumb (“A therapist is not a friend,” or “Once a client, always a client”).

Consumer-therapeutic justifications (40 percent) were those based primarily on the immediate interests of the client—his or her dignity, well-being, therapeutic progress, and so on. Examples of responses included “It’s the client’s decision,” “It depends on the individual client,” “I would deal with it in therapy as part of the transference,” “Doing this models prosocial behavior for the client,” “This would be countertherapeutic,” or “The consumer needs to face natural consequences.”

Four miscellaneous categories were used for completeness but not studied further. Personal-policy justifications (9 percent) made no direct or explicit reference to any principle or guideline but instead cited a personal value or rule of thumb. Examples included “I do not feel comfortable doing this,” “It’s not my style,” “I’d have to do it for all clients,” “I would let this go,” “I can keep professional and personal issues separate.” The propose-alternative category (2 percent) was used for answers that did not provide a clear ethical justification and instead offered an alternative course of action. For example, one respondent stated that after committing a confidentiality violation, the provider should obtain the client’s signature retroactively on a form for the release of confidential information.

Consult team-supervisor responses (2 percent) did not directly justify the yes-no decision but said simply that the respondent would seek input from the supervisor or team (for example, “Staff this problem”). Finally, 3 percent of answers were blank or were too ambiguous or confusing to code in any of the above ways.

Some justifications were lengthy, and a few (12 percent) included ideas relevant to more than one coding category. In such cases the first response was generally the one on which coding was based. However, if information appropriate to formal-policy or consumer-therapeutic justifications was included, either of these substantive categories was used in preference to the miscellaneous categories. If clear evidence for both formal-policy and consumer-therapeutic justifications was present, formal policy was coded to credit the respondent with adhering to a formal policy.

After developing and refining these categories based on 37 surveys (518 total responses), the first and third authors independently coded the justifications used in 23 additional surveys (322 responses), achieving satisfactory interrater reliability (kappa=.66). The third author then coded the remaining 35 surveys. For all 95 surveys, any uncertainties or disagreements were resolved by discussion between the first and third authors.

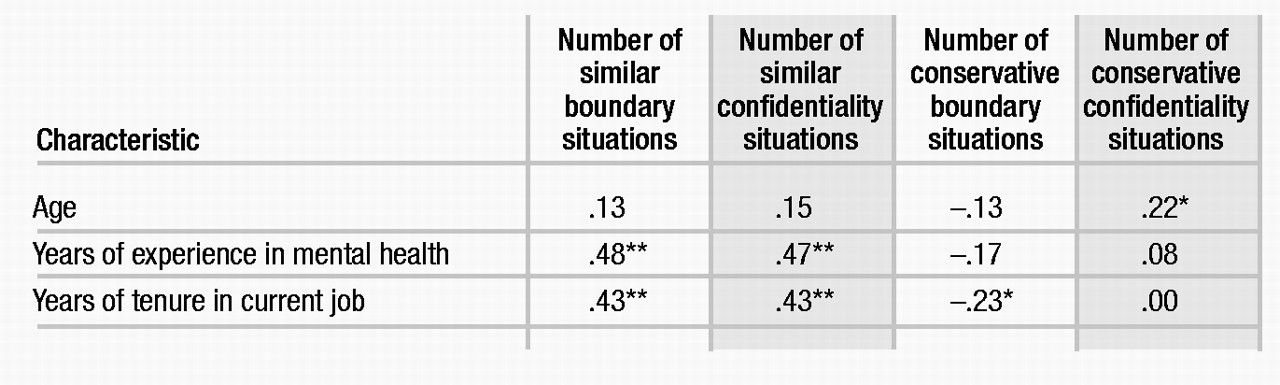

The dependent variables were the number of boundary and confidentiality dilemmas similar to those in the vignettes that the respondent had experienced, the number of conservative decisions made in boundary and confidentiality dilemmas, and the number of formal-policy and consumer-therapeutic justifications cited for each kind of dilemma. Pearson correlation coefficients were computed between these variables and providers’ age, years of experience as a mental health provider, and years of tenure in their current position. Relationships of providers’ sex, ethnicity, level of education, current position, and major field of study to each dependent variable were examined using one-way analyses of variance of differences between subgroup means, with modified least significant difference (Bonferroni) tests (p=.05).

The effects of previous ethics training and rural-nonrural setting were tested using repeated-measures analyses of covariance, with one covariate (overall years of experience), two between-subjects factors (previous ethics training and rural-nonrural setting), and one within-subjects factor (type of dilemma—boundary or confidentiality). Because there were ten boundary dilemmas but only four confidentiality dilemmas, the dependent variables in the latter design were the proportions of similar situations, conservative decisions, policy justifications, and consumer justifications associated with each type of dilemma.

Results

As shown in Table 2, staff with more years of mental health experience or longer tenure in their current jobs had experienced more boundary and confidentiality dilemmas similar to those in the vignettes. Those with longer tenure in their current jobs also made fewer conservative decisions in response to boundary dilemmas. Older providers made a greater number of conservative decisions in confidentiality dilemmas than did younger providers.

For the most part the effects of sex, ethnicity, level of education, major field of study, and current position were nonsignificant. Two exceptions were that supervisors had experienced a significantly greater number of similar situations involving boundary dilemmas than had entry-level staff (means of 4.4 and 2.3 situations; F=3.7, df=3,90, p=.01), and that the most educated staff (postgraduate) were more likely to use formal-policy justifications for boundary dilemmas than were the least educated staff (those having some college or less) (4 versus 2.6; F=3.5, df=2,92, p=.04).

Controlling for years of experience, providers with previous ethics training reported more boundary dilemmas (mean=4.3) and confidentiality dilemmas (mean=1.7) similar to those in the vignettes than did providers without ethics training (means=2.6 and .8, respectively) (F=8.2, df=1,89, p<.01). Rural providers had experienced about the same number of confidentiality dilemmas as nonrural providers (1.3 and 1.4, respectively), but rural providers reported more boundary dilemmas than did nonrural providers (4.3 versus 3.4; F=5.9, df=1,90, p<.02).

Experience, previous ethics training, and the clients’ sex were unrelated to providers’ ethically conservative decisions. However, conservative decisions were made in a greater proportion of confidentiality dilemmas than boundary dilemmas (.86 versus .66; F=46.9, df=1,81, p<.001), and rural providers made fewer conservative decisions than did nonrural providers (.71 versus .77; F=4.3, df=1,80, p<.05). Although the rural-nonrural difference in the proportion of conservative decisions was greater for boundary dilemmas (.59 versus .68, respectively) than for confidentiality dilemmas (.82 versus .86), this interaction was not significant.

The only significant effect for ethical justifications was that formal-policy justifications were more likely to be made for a confidentiality dilemma than for a boundary dilemma (.70 versus .35), and consumer-therapeutic justifications were more likely to be made for a boundary dilemma than for a confidentiality dilemma (.47 versus .24; F=47.8, df=3,270, p<.001).

Discussion and conclusions

The results suggest that in community-based services for persons with serious mental illness, boundary issues are encountered frequently and are not always dealt with conservatively, especially in rural communities. The data also show that providers’ justifications for their ethical decisions can reflect clients’ interests as well as formal policies, especially when the ethical dilemma involves a boundary issue. Providers’ years of experience and previous ethics training were independently related to having experienced dilemmas similar to the ones studied, but these variables were not related to decision making or justifications. The providers’ sex, ethnicity, and age had little or no influence on ethical decisions and reasoning, for which the best overall predictor was working in a rural setting.

These findings confirm that treatment plans and contracts should address gray areas in writing (for example, loaning money and contacts with third parties), and that any dilemmas encountered, decisions made, and justifications used should be documented in detail (

2). Given the complexity of some situations and the evolving nature of community-based services, we should not expect to promote clear, sound ethical reasoning simply by prescribing do’s and don’t’s. Instead, we should encourage a process that gives explicit attention to ethical gray areas and to educating clients in boundary and privacy issues.

A focus on the decision-making process makes ethical reasoning less intuitive or rote and more based on understanding an interpersonal problem as an ethical dilemma and recognizing that the available decisions have differing value implications (

7). Boundary problems not only threaten the client’s well-being and the effectiveness of treatment; they can also harm the provider (

3). Increased use of provider teams, rather than individual caseloads, may offer a safeguard against boundary and privacy violations, as would more use of direct collaboration with others in the consumer’s natural context, such as family members (

23).

The decisions studied here were hypothetical. To understand what individual staff think, we contrived the vignettes so participants were forced to make an immediate decision with no opportunity to check with a supervisor or obtain a release of confidential information. Thus providers’ real-life decisions might not always have been the same as those reported here. Furthermore, the ten boundary dilemmas and four confidentiality dilemmas were weighted equally, yet evidence (

17) and common sense suggest that they vary in seriousness. Our coding of some decisions reflected our special focus on front-line providers who lack extensive professional training, such as training to process a client’s transference. For example, a participant’s decision to work through a client’s crush therapeutically instead of transferring the client to another was coded as a less conservative, boundary-crossing decision.

In general, however, these vignettes and participants’ responses to them were meaningful and informative and demonstrate that providers are sensitive to ethical dilemmas, make careful decisions, and justify their decisions in ethically defensible ways. For each vignette, many providers indicated that they had had a similar experience, and many also suggested alternative courses of action that might have resolved the dilemma, demonstrating the relevance of these dilemmas to their work experiences.

With public policy geared to expanding case management and other high-intensity community-based services for persons with serious mental illness, a better understanding of ethical risks and practices will improve the effectiveness and efficiency of services and the training and supervision of staff. Coupled with more attention to overlapping client-provider relationships in nonurban communities, promoting ethically sound practice will be increasingly important as more clients become providers and the impact of consumer self-help groups reduces the interpersonal distance between givers and receivers of help.