Design

The studies were initiated in late 1986 and completed in 1995. During hospitalization for an index episode, 186 patients who had just been admitted to the inpatient schizophrenia unit of Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic met eligibility criteria for the outpatient maintenance studies and gave informed, signed consent to participate in the studies after the benefits and risks had been fully explained. Eligibility for the studies included a Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) (

35) diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder; age 16 to 55 years; IQ above 75; the absence of organic brain syndrome and serious alcohol or drug abuse or dependence in the previous 6 months that significantly impaired adjustment; and no medical contraindications that precluded taking maintenance antipsychotic medication. We estimate that, as is common with such criteria, only 25% of all patients with schizophrenia admitted to the inpatient unit were eligible for study; the majority (perhaps 60%) were excluded for reasons of serious drug or alcohol abuse and/or diagnostic uncertainty. (The reasons for ineligibility were not archived.)

Following hospital discharge, 35 of the 186 patients either never returned to the research clinic or returned briefly but refused further treatment (N=25); were administratively terminated from the study for reasons of relocation, disposition to a state hospital, or accidental death (N=6); or had a change of diagnosis from schizophrenia to organic brain syndrome (N=4).

The remaining 151 patients qualified for one of two distinct, concurrent trials and were treated as outpatients under controlled conditions for 36 months. In trial 1, 97 patients who resided with family were randomly assigned to one of four conditions: personal therapy, family psychoeducation/management (family therapy), a combination of personal therapy and family psychoeducation/management (combination personal and family therapy), or supportive therapy. In trial 2, 54 patients who lived either alone or in shared quarters with nonrelatives were randomly assigned to personal therapy or supportive therapy. (One patient who had been living alone before the study returned to her mother’s home during the study and withdrew from personal therapy at 18 months when she relapsed. Since this patient did not positively bias the findings regarding the effects of personal therapy and satisfied the criterion of “intent to treat,” she was included in all appropriate analyses.)

All patients in both trials were prescribed antipsychotic medication, adjusted in the initial months of treatment to the minimum effective neuroleptic dose, i.e., the dose below which prodromes of a new episode were likely to emerge but above which more than mild hypokinetic rigidity was observed (

36). Medication was prescribed by two part-time, experienced psychiatrists, and medication management was supervised by four master’s-level psychiatric nurse clinical specialists.

Since the adequacy or control of antipsychotic medication might have compromised the understanding of previous psychotherapy effects, medication records were analyzed in detail regarding antipsychotic drug compliance as well as type, dose, and route of administration by year, trial, and treatment condition in a search for systematic differences that might influence outcome independent of psychosocial treatment. No such differences were found.

A majority of the patients received intramuscular fluphen-azine or haloperidol decanoate throughout the study: 109 (72%) of 151 patients in year 1, 84 (62%) of 135 patients in year 2, and 74 (59%) of 126 patients in year 3. Approximately half of the recipients of intramuscular medications in year 1 and one-fourth in years 2 and 3 also received a supplemental oral neuroleptic as needed. The remaining patients—42 (28%), 51 (38%), and 52 (41%) in year 1, 2, and 3, respectively—received oral antipsychotics exclusively, and the number increased as more patients were maintained on a regimen of clozapine over time (e.g., 11 of 151 patients in the first year and 23 of 126 patients during year 3). There were no trial or treatment condition differences in route of administration.

Medication noncompliance was infrequent. For example, 76% of scheduled intramuscular injections were received as prescribed, and only 21% were late by 1–6 weeks. Similarly, 89% of oral doses were judged by the medication nurse to have been taken as prescribed, and only 9% were believed to have been missed for 1–6 weeks. (Plasma or urine assays designed to validate these judgments were not made.)

Total neuroleptic doses prescribed, expressed in weekly mean dose equivalents of fluphenazine decanoate, were 7.16 mg (SD=6.23) in year 1, 6.88 mg (SD=6.25) in year 2, and 6.93 mg (SD=6.49) in year 3. No differences were observed by year or within a trial; however, somewhat higher neuroleptic doses were prescribed for the patients who were not living with family. The mean dose of clozapine was 330 mg/day (SD=150) across years; there were no trial or treatment condition differences in dose. However, by year 3, 27% (N=12) of the 45 patients who were not living with family, compared with only 14% (N=11) of the 81 patients who were living with family, were being maintained on a regimen of clozapine. There were no important antipsychotic medication differences within trials that would confound psychosocial treatment effects, but the facts that patients living independent of family received higher neuroleptic doses and that a higher percentage of these patients were maintained on a regimen of clozapine are indications of their more extensive psychiatric histories.

Most patients received supplemental thymoleptics as needed, and half were prescribed an antiparkinsonian medication at some time during the study; no significant differences were observed in these medications between or within trials.

The needs of all study patients that related to stable housing, health care, and entitlements were addressed by the patients’ primary clinician, independent of treatment condition. Relapsed patients were returned to their original treatment condition on symptom remission, typically to a phase of intervention (in personal and family therapy) below that previously attained.

Personal therapy was provided by two of four full-time, master’s-level psychiatric nurse clinical specialists and three part-time doctoral-level clinical psychologists. Family therapy was provided by the other two full-time master’s-level psychiatric nurse clinical specialists and by one part-time master’s-level psychologist. Supportive therapy was provided by the same project nurses who served as personal or family therapists. Patients assigned to the combined personal and family therapy condition had both a personal therapist and a family therapist. Seven of eight therapists were female, and all were white. All but two part-time psychologists had 15 to 21 years of experience working with schizophrenic patients, most in the context of this longstanding research program. Fidelity to personal, family, and supportive therapy was facilitated by explicit treatment manuals as well as by weekly individual and peer-group supervision provided by two senior (doctoral level) clinical supervisors and/or the principal investigator and by treatment process ratings that identified the practice principles used and the goals achieved. Therapist continuity was consistent: one part-time personal therapist left the study at mid-point and one full-time family therapist left 1 year before study termination. Only four personal therapy, three family therapy, and four supportive therapy patients experienced a change of clinician during the study.

All but eight personal therapy and/or family therapy patients met a priori criteria for treatment exposure that required a predetermined number of sessions as well as the acquisition of skills and their application (personal and family therapy) and/or receipt of medication. Since all eight patients were approximately distributed across personal therapy and family therapy cells and attended the clinic with regularity to the time of study completion or termination, they were included in all appropriate analyses, having at least satisfied the criterion of “intent to treat.” The small number precluded the separate analysis of “partial treatment takes” attempted in a previous study (

12).

Definitions of treatment

Personal therapy. A detailed description of personal therapy is available elsewhere (

34). Briefly, personal therapy sought to forestall the late (second-year) relapse common among modern psychosocial approaches (

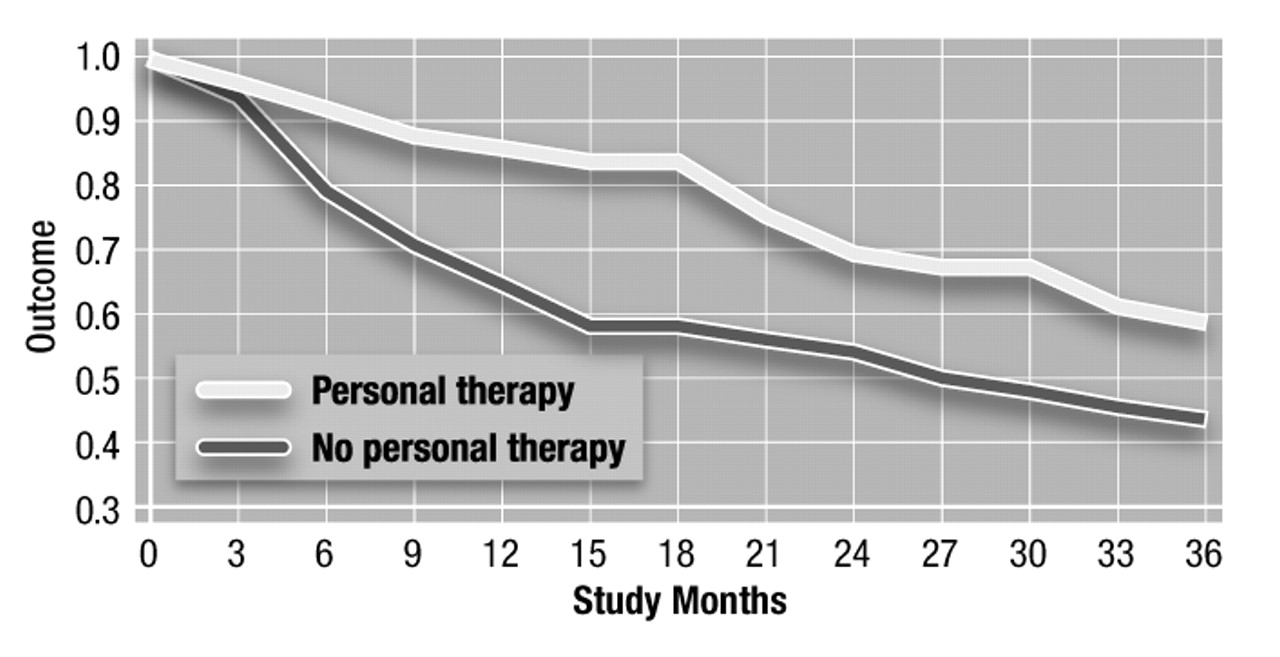

12). Personal therapy also sought to enhance personal and social adjustment through the identification and effective management of affect dysregulation that was believed to either precede a psychotic relapse or provoke inappropriate behavior that was possibly generated by underlying neuropsychological deficits. Personal therapy was applied in a graduated, three-stage, systemic approach in recognition of the sensitivity to therapeutic intensity of many schizophrenic patients (

34). Through a process called “internal coping,” personal therapy encouraged the patient to identify the affective, cognitive, and physiological experience of stress. The appraisal of stress and the effect of its subsequent expression on the behavior of others was also facilitated. Personal therapy focused on the patient’s characteristic response to stress in general rather than on the idiosyncratic response to a specific stressor. It avoided symbolic interpretation and clarification of unconscious motives and drives. Whereas our earlier studies of family and behavioral approaches (

12) sought to gain direct or indirect control over the external sources of stress that appeared to precipitate relapse, personal therapy focused on the patient’s internal sources of dysregulation. Analyses of the relapse process (

37,

38), whether in stage or continuum models, had indicated that “prodromes” of a new episode most often included aspects of impaired affect.

The basic phase of personal therapy was typically applied in the early months after discharge. Following principles that were useful for establishing a therapeutic alliance and achieving clinical stabilization, therapists offered formation of a treatment contract, provision of minimum effective dosing, basic psychoeducation regarding the nature and treatment of schizophrenia, and techniques of supportive therapy to personal therapy recipients as well as to supportive therapy patients. (Principles of supportive therapy included active listening, correct empathy, appropriate reassurance, reinforcement of patient health-promoting initiatives, and reliance on the therapist for advocacy and problem solving in times of crisis.)

Additional strategies were reserved exclusively for personal therapy recipients in the basic phase. These included a step-by-step plan for the resumption of expected roles and the provision of social and avoidance techniques from social skills training that had earlier been associated with positive 1-year outcomes (

39). Internal coping was introduced to personal therapy recipients initially to determine the relationship between stressors as possible triggers and symptom exacerbation. Patients needed to meet certain criteria to advance to the next phase; these criteria included symptom stability, achievement of a stable dose of maintenance medication, and evidence that they had applied selected social skills strategies.

The intermediate phase most often occurred during the first 18 months after discharge. Patients were provided advanced psychoeducation that included a didactic on the adaptive strategies to be taught, the requirements for a successful rehabilitation, and a more formal focus on the prodromes of psychosis. Internal coping strategies progressed to the identification of individual cognitive, affective, and somatic indicators of distress and the appropriate application of basic relaxation (diaphragmatic breathing) and cognitive reframing techniques. In addition, skills training designed to ameliorate social behavior deficits (if needed) and to enhance social perception abilities was introduced. Patients who were able to meet additional clinical criteria moved to the advanced phase of treatment. These criteria included an understanding of the personal effects of stress, acquisition of social perception skills, continued stabilization, and application of basic relaxation techniques.

In the advanced phase, which usually occurred in the last 18 months of treatment, the therapist encouraged the timing of social and vocational initiatives in the community, awareness of one’s individual prodromes, progressive relaxation principles, and a growing awareness of one’s affect, together with its expression and perceived effect on the behavior of others. This latter phase also included instruction in principles of criticism management and conflict resolution. A simulated vocational setting was provided so that the patient could be observed applying acquired skills in “real-life” situations and any need for continuing remediation could be identified.

As described elsewhere (

34), the many strategies embodied in personal therapy were not applied in equal “doses” to every patient. Rather, selected principles of personal therapy were tailored to patients’ individual needs. For example, not all patients required or preferred systematic muscle relaxation, but nearly all used deep breathing exercises.

Family therapy. In trial 1, family therapy followed the graduated stages and process that we have described in detail elsewhere (

40). These included the three broad phases of joining, survival skills training and reintegration within the home, and reintegration into the community. The principal modification to the family therapy approach was a change in didactic content that reflected issues of importance to the families of first-episode patients (

41), such as diagnostic uncertainty and variable prognosis. (Twenty-seven percent [N=26] of patients who lived with family in trial 1 were first-episode patients.) Unlike our past study (

12), which excluded households with low ratings for expressed emotion, families with both high and low ratings for expressed emotion were included in trial 1.

Eight percent of the patients (and families) in the personal and family therapy conditions failed to move beyond the basic phase of their respective treatments in trial 1. Approximately 38% of personal therapy patients entered but did not advance beyond the intermediate phase, and 40% of the families entered but did not advance beyond the middle phase of family therapy. Fifty-four percent of personal therapy patients and 52% of family therapy patients and families completed the intermediate phases and entered and/or completed the advanced phases of treatment. Constraints against advancement in personal and family therapy were found in the patient’s clinical state and/or family resistance, as well as from limitations imposed by the length of research support. Process analyses of variables that facilitated or impeded advancement in treatment will be the subject of a future report.

Table 1 shows the average number of monthly in-person treatment sessions and the significant differences between treatment conditions for trials 1 and 2 combined. Treatment sessions were 30–45 minutes long. There were no significant differences in frequency of contact among the three personal therapy cells, the two family therapy cells, and the two supportive therapy cells; therefore, the trials were pooled by treatment condition. Personal therapy sessions were, as designed, significantly more frequent than family therapy and supportive therapy sessions in each treatment year. Personal and family therapy patients also received 1.9 additional monthly medication management sessions in years 1 and 2, and an additional 1.3 sessions each month in year 3. These were brief (15-minute) contacts that usually followed a scheduled personal or family therapy session and were provided to assure that each study patient received the medication management services of a nurse clinical specialist. (Medication management was an integral part of each supportive therapy session provided by the nurses.) Although supportive therapy sessions were less frequent than personal therapy sessions, the 21 annual visits of supportive therapy recipients exceeded the 16 annual visits that are customary in outpatient mental health facilities (

42). Actual session frequency approximated the intended frequency: weekly sessions for personal therapy recipients over 3 years, with less contact in year 3 for those who completed treatment objectives; biweekly family sessions for family therapy recipients in year 1, with biweekly to monthly sessions thereafter; and biweekly sessions for supportive therapy recipients in all years. It was not logistically feasible to insist that families and patients in the no-personal-therapy conditions attend more often in order to equalize session frequency. Rather, frequency was dictated by the therapeutic requirements of the respective treatment. However, if necessary, patients in all treatment conditions were seen more often at times of crisis or symptom exacerbation either by their primary therapist or by the Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic emergency room staff during evenings or weekends.