Although illness management and recovery are intertwined, almost all the available treatment research pertains to illness management. Thus we confined our research review to studies of illness management programs. Because extensive research has been conducted on illness management, we confined our review to randomized clinical trials. We also limited our review to programs that addressed schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and the general group of severe or serious mental illnesses, excluding studies that focused on major depression or borderline personality disorder. Studies included in this review were identified through a combination of strategies, including literature searches on PsycINFO and MEDLINE, inspection of previous reviews, and identification of studies presented at conferences.

With respect to outcomes, we examined the effects of different interventions on two proximal outcomes and three distal outcomes. The proximal outcomes are knowledge of mental illness and using medication as prescribed. The distal outcomes are relapses and rehospitalizations, symptoms, and social functioning or other aspects of quality of life. Distal outcomes are of inherent interest because they are defined in terms of the nature of the mental illness and associated problems. Proximal outcomes are of interest because they are related to important distal outcomes. Specifically, knowledge of mental illness is critical to the involvement of people with psychiatric disorders as informed decision makers in their own treatment (

14,

15). Using medication as prescribed is important because medications are effective for preventing symptom relapses and rehospitalizations for persons with severe mental illness (

43,

44), yet many people do not take medications (

45), and nonadherence accounts for a significant proportion of relapses and inpatient treatment costs (

46). Although adherence to medication regimens is important in and of itself, illness management approaches involve forming partnerships between clinicians and persons with a mental illness in order to determine the services each person needs, including medication, and respecting patients’ rights to make decisions about their own treatment (

36).

The literature review was divided into five areas: broad-based psychoeducation programs, medication-focused programs, relapse prevention, coping skills training and comprehensive programs, and cognitive-behavioral treatment of psychotic symptoms.

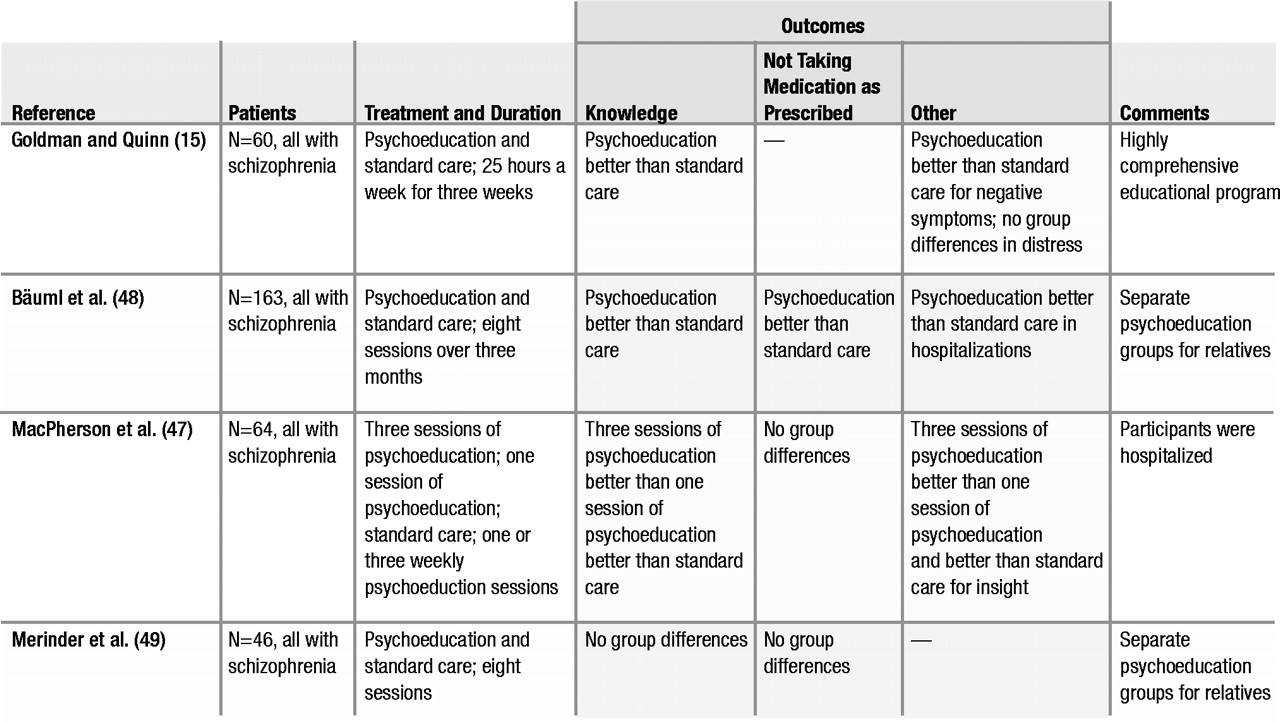

Broad-based psychoeducation programs

Most broad-based programs, summarized in Table 1, provided information to people about their mental illness, including symptoms, the stressvulnerability model, and treatment. Among the four controlled studies, all but one (

47) provided at least eight sessions of psychoeducation. Follow-up periods ranged from ten days (

15) to two years (

48). Three of the controlled studies found that psychoeducation improved knowledge about mental illness (

15,

47,

48); one did not (

49). In two studies, improved knowledge had no effect on taking medication as prescribed (

47,

49); one study reported improved adherence (

48).

In summary, research on broad-based psychoeducation indicates that it increases participants’ knowledge about mental illness but does not affect the other outcomes studied. This finding may not be surprising: similar didactic information given to families of persons with schizophrenia has been found to increase their knowledge but not to affect their behavior (

50,

51). The reason for this may be that didactic information does not consider beliefs and illness representations already held by recipients (

52). Nevertheless, psychoeducation remains important because access to information about mental illness is crucial to people’s ability to make informed decisions about their own treatment, and psychoeducation is the foundation for more comprehensive programs (as reviewed below).

Medication-focused programs

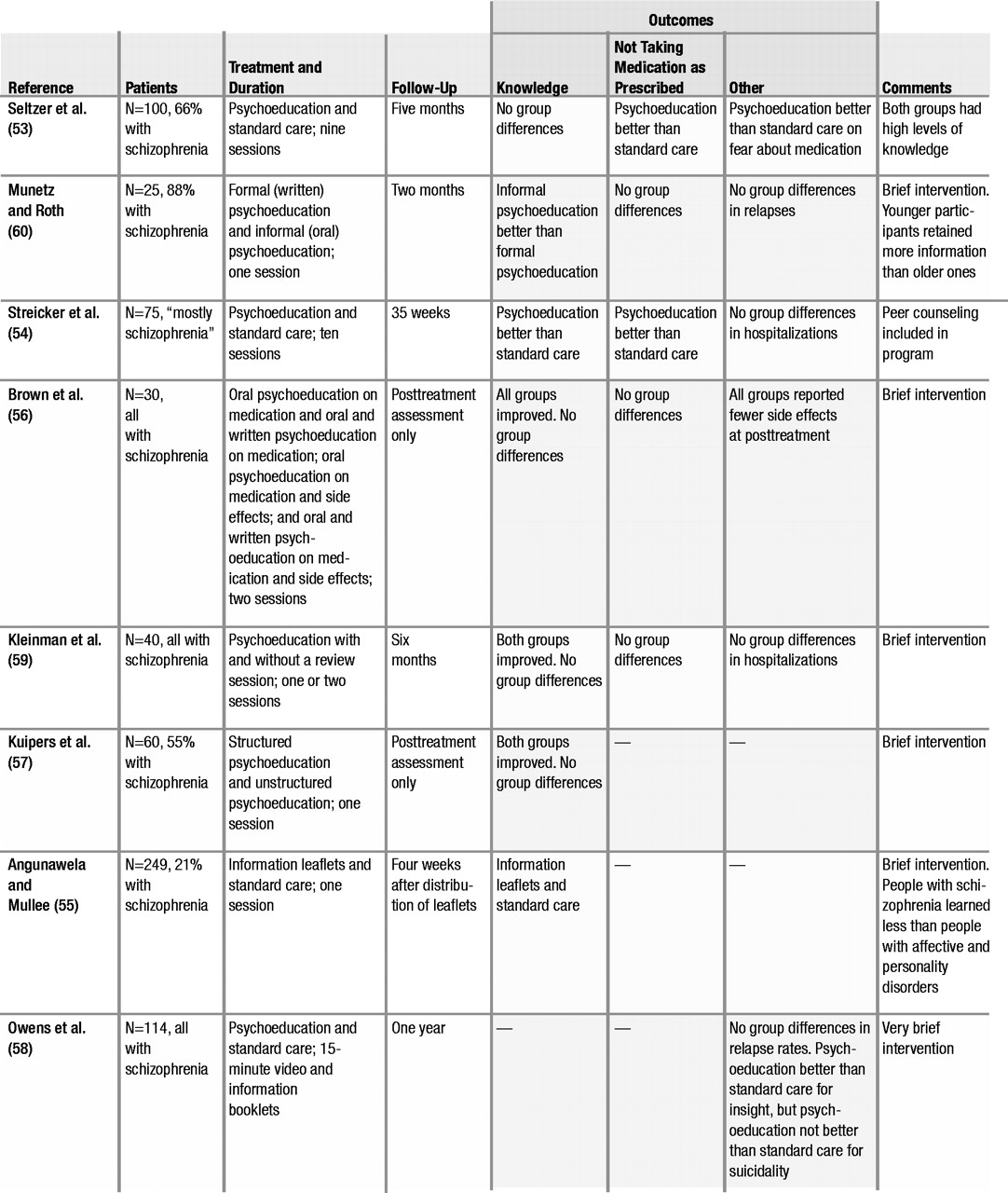

Studies that strove to foster collaboration between people with a mental illness and professionals regarding taking medication used psychoeducational or cognitive-behavioral approaches or a combination of the two.

Psychoeducation about medication involves providing information about the benefits and the side effects of medication and teaching strategies for managing side effects, so that people can make informed decisions about taking medication. These programs, summarized in Table 2, tended to be brief, with only two of eight programs (

53,

54) lasting more than one or two sessions. Three studies conducted posttreatment-only follow-up assessments (

55–

57), and five studies conducted follow-ups after the end of treatment (

53,

54,

58–

60). Most of the studies reported that participants increased their knowledge about medication. However, three studies reported no group differences in taking medication as prescribed (

56,

59,

60); a fourth study reported improvements (

53); and a fifth study reported deterioration in taking medication (

54). The three studies that found no differences in taking medication as prescribed compared different psychoeducational methods (

56,

59,

60). Only one study that assessed medication adherence included a no-treatment control group (

54); this study found that clients who received psychoeducation were more likely than clients who received no psychoeducation to discontinue medication. A somewhat disconcerting finding was reported in the only other study with a no-treatment control group (

58). This study found that psychoeducation increased clients’ insight into their illness but also increased clients’ suicidality; psychoeducation had no influence on other symptoms or on relapse rates. In summary, research on the effects of psychoeducation about medication indicates that it improves knowledge about medication, but little evidence indicates that it improves taking medication as prescribed or affects other areas of functioning.

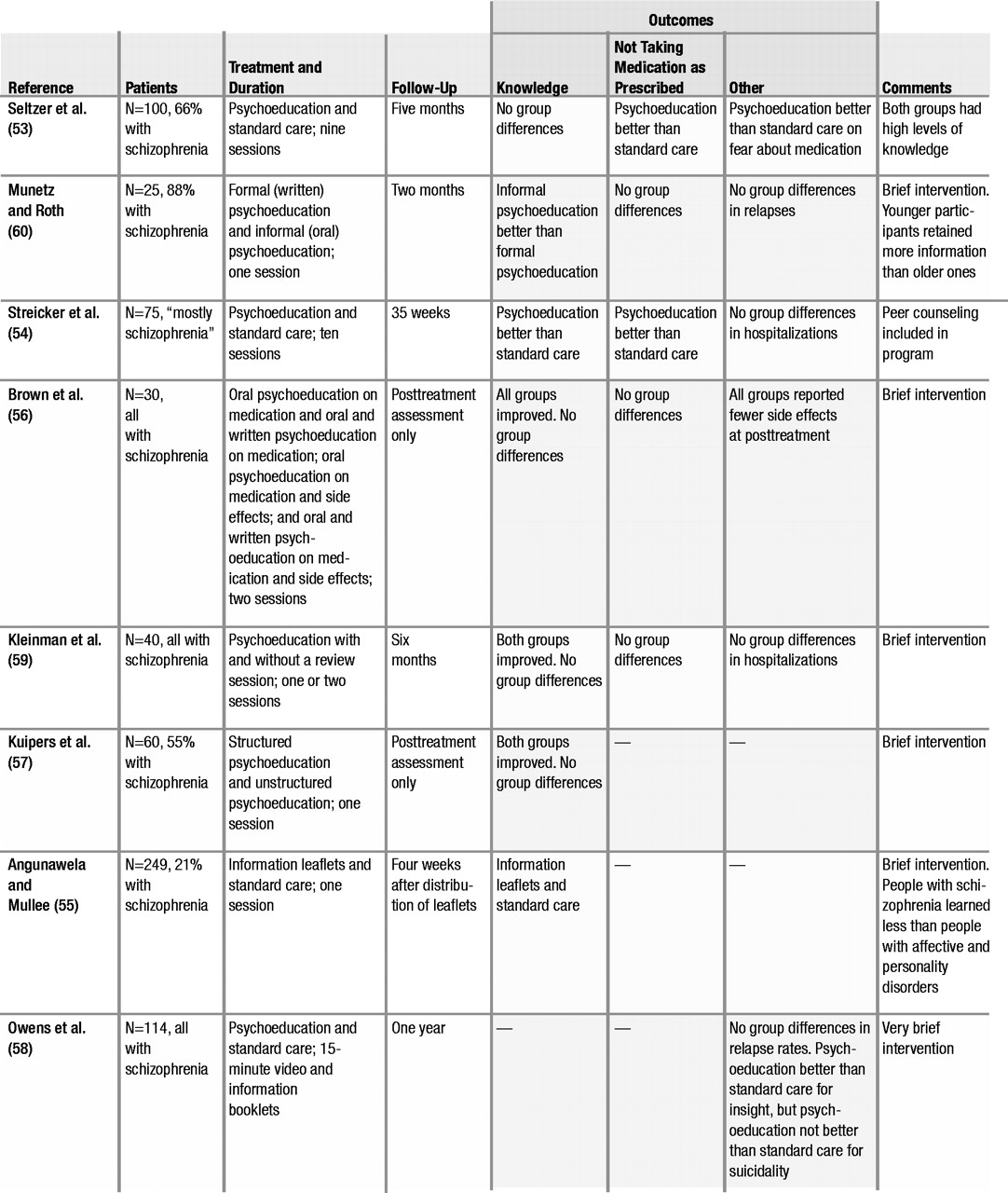

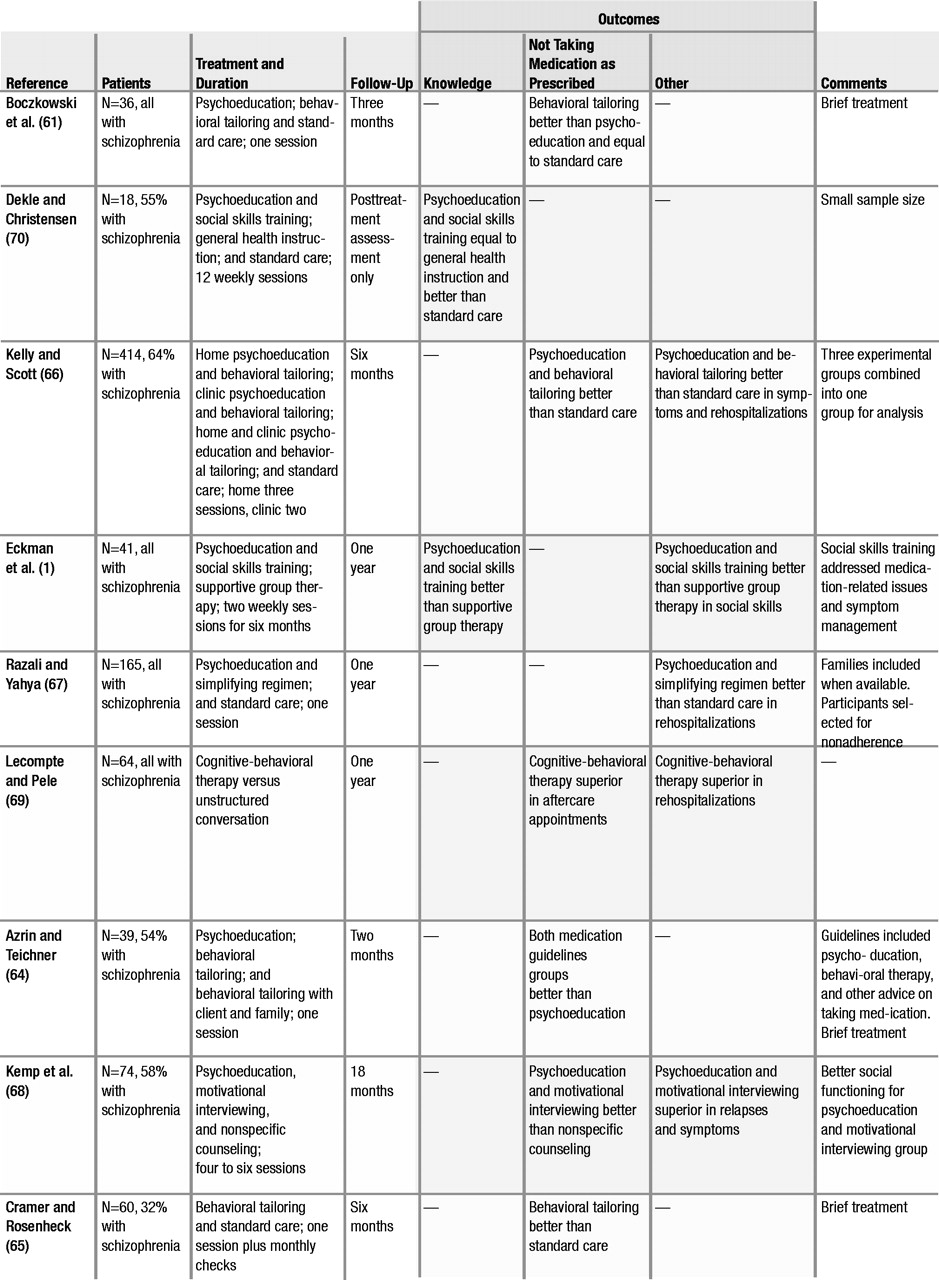

Cognitive-behavioral programs that focused on medication used one of several techniques: behavioral tailoring, simplifying the medication regimen, motivational interviewing, or social skills training. Behavioral tailoring involves working with people to develop strategies for incorporating medication into their daily routine—for example, placing medication next to one’s toothbrush so it is taken before brushing one’s teeth (

61). Behavioral tailoring may also include simplifying the medication regimen, such as taking medication once or twice a day instead of more often. Motivational interviewing, based on the approach developed for the treatment of substance abuse (

62), involves helping people articulate personally meaningful goals and exploring how medication may be useful in achieving those goals. Social skills training involves teaching people skills to improve their interactions with prescribers, such as how to discuss medication side effects (

63).

Cognitive-behavioral programs for medication are summarized in Table 3. All four studies of behavioral tailoring found improvements in taking medication as prescribed (

61,

64–

66), as did the one study that evaluated the effect of simplifying the medication regimen (

67). One study of motivational interviewing (

68) also reported an increase in taking medication as prescribed, as well as fewer symptoms and relapses and improved social functioning. One broad-based cognitive-behavioral program also reported lower rates of rehospitalization (

69). The two studies that examined social skills training were limited. One of these studies found that skills training had no effect on knowledge about medication, but medication adherence was not directly assessed (

70). The other study showed that psychoeducation and skills training improved knowledge and social skills in medication-related interactions, but it did not assess taking medication as prescribed (

71).

Thus controlled research, which has focused mainly on individuals with schizophrenia, provides the strongest support for the effects of cognitive-behavioral methods (chiefly, behavioral tailoring) for increasing their taking of medication as prescribed, whereas psychoeducation alone has limited, if any, impact. The strong effects of behavioral tailoring on taking medication, compared with the weak effects of psychoeducation, suggest that memory problems, which are common in schizophrenia (

72), may interfere with taking medication as prescribed and that behavioral tailoring may work by helping people develop their own cues to take medication, thereby compensating for cognitive impairments.

Most of the programs reviewed were response-based, with little effort made to understand the psychology of why people did not take medication as prescribed. This is very different from the theoretical position in health psychology, in which complex models such as the health belief model and the theory of planned action have been developed to understand health-related behavior. Preliminary studies investigating medication self-administration have used the concept of psychological reactance, which is a motivational state that can develop when a person perceives a threat to his or her personal freedom (

73). In an analogue study, reactance-prone individuals rated themselves as being less likely to take medication if their freedom of choice was restricted, whereas no effect of freedom of choice was seen in non–reactance-prone participants (

74). In a study of people with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, individuals with higher psychological reactance who perceived taking medication as a threat to their freedom of choice were less likely to have taken medication as prescribed in the past (

75). Motivational interviewing may provide one strategy for improving people’s understanding of medication and addressing their concerns about taking medication, while respecting their decision about whether or not to use medication. However, only one controlled study has evaluated the effects of motivational interviewing on taking medication as prescribed, and this study is in need of replication.

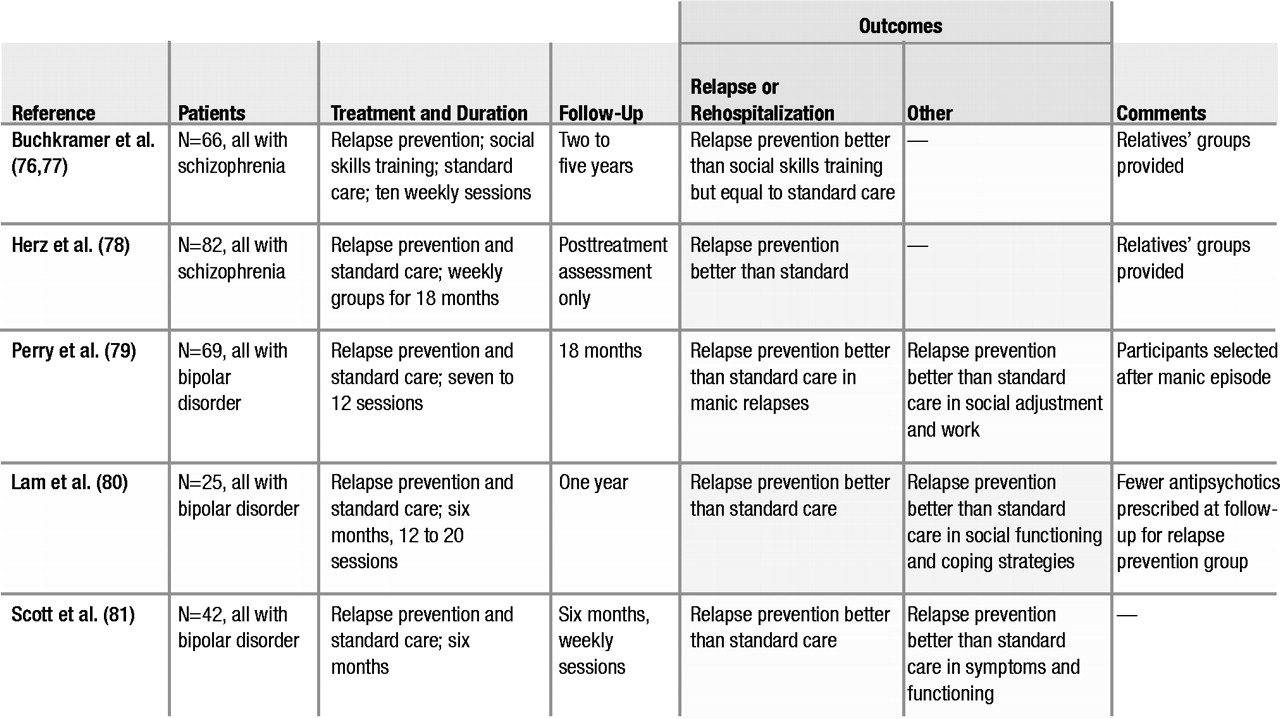

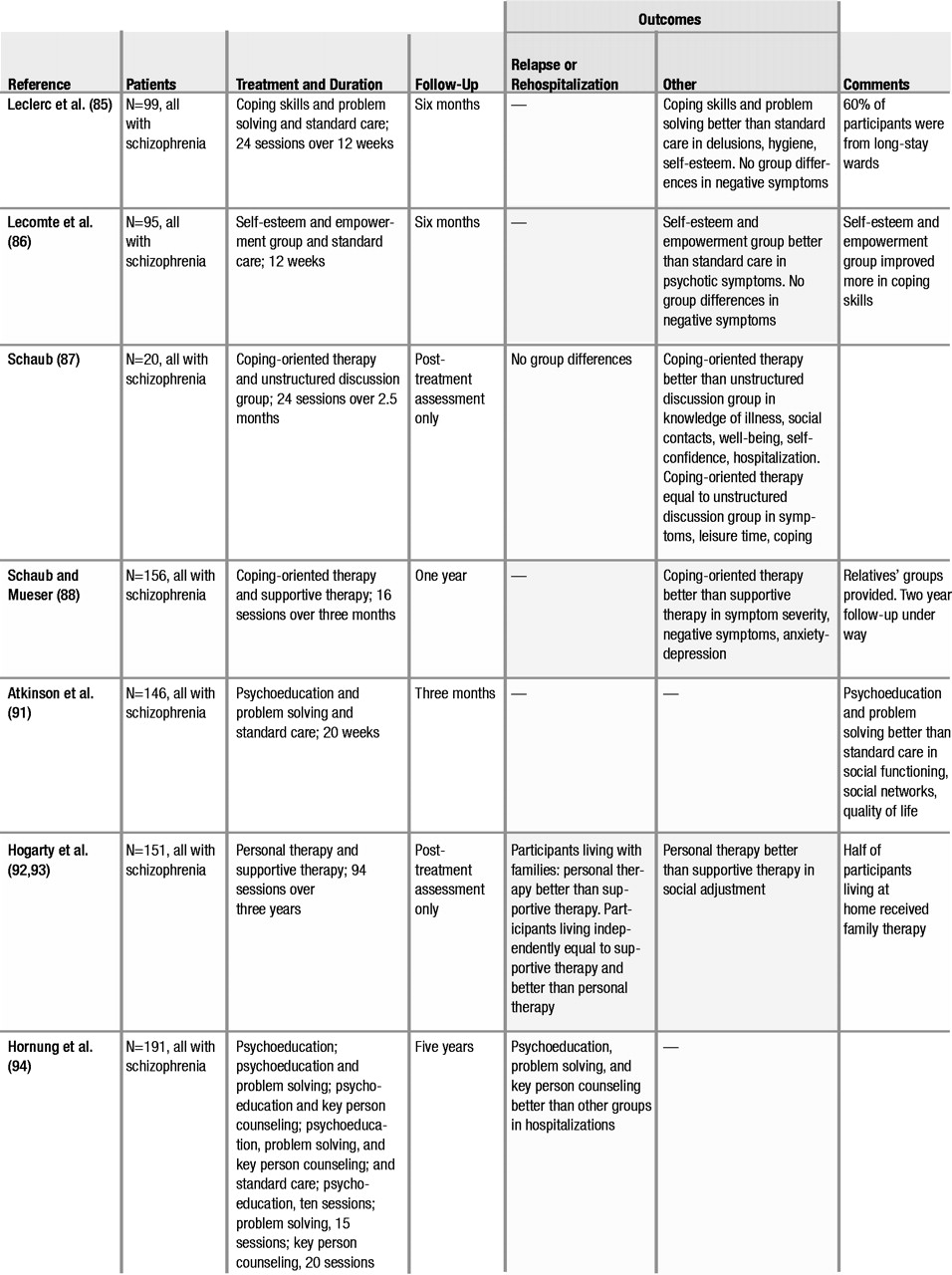

Coping skills training and comprehensive programs

Controlled studies of coping skills training and comprehensive programs are summarized in Table 5. Coping programs aim to increase people’s ability to deal with symptoms or stress or with persistent symptoms (

85–

90). Comprehensive programs incorporate a broad array of illness management strategies, including psychoeducation, relapse prevention, stress management, coping strategies, and goal setting and problem solving (

91–

94).

The four studies of coping skills were quite different, both in the methods employed and in the targets of the intervention. Leclerc and colleagues (

85) taught an integrative coping skills approach based on Lazarus and Folkman’s model of coping (

95,

96), which emphasizes the importance of cognitive appraisal in perceiving threat. Lecomte and colleagues (

86) addressed general coping skills through building up participants’ sense of empowerment. Schaub (

87) and Schaub and Mueser (

88) taught skills for managing stress and persistent symptoms, combined with basic psychoeducation about schizophrenia. Despite the differences in the programs, all the coping skills programs employed cognitive-behavioral techniques and produced uniformly positive results in reducing symptom severity. Thus research evidence shows that coping skills training is effective.

The three studies of comprehensive programs—that is, those using a broad range of techniques—are somewhat difficult to compare because they differed in the clinical methods used. Atkinson and coworkers (

91) evaluated a program that combined morning educational presentations and afternoon sessions in which problem solving was applied to the educational topics. Hogarty and associates (

92,

93) evaluated the effects of personal therapy, a broad-based approach incorporating psychoeducation, stress management, and development of adaptive coping skills to promote social reintegration, and compared these effects with the effects of supportive therapy. They found that personal therapy prevented relapses only for people living with families. However, people receiving personal therapy improved in social functioning, whether they were living at home or not. Hornung and colleagues (

94) examined the effects of different combinations of psychoeducation, problem-solving training, and key-person counseling (such as counseling family members) and found that people who received all three had fewer relapses over five years. These three studies suggest that comprehensive programs improve the outcome of schizophrenia, but the differences between programs preclude any definitive conclusions about which approaches may be most effective.

Cognitive-behavioral treatment of psychotic symptoms

Over the past 50 years, since the early work of Beck (

97), cognitive-behavioral therapy has been used to help clients with psychotic symptoms cope more effectively with the distress associated with symptoms or to reduce symptom severity. Cognitive-behavioral approaches to psychosis include teaching coping skills, such as distraction techniques to reduce preoccupation with symptoms (

98), and modifying clients’ dysfunctional beliefs about the illness, the self, or the environment (

99). In recent years, several manuals have been developed for cognitive-behavioral therapy for psychosis (

100–

102).

Over the past decade, eight controlled studies of time-limited cognitive-behavioral therapy for psychosis have been conducted—six in England (

89,

90,

103–

112), one in Canada (

113), and one in Italy (

114). Because several comprehensive reviews of this research (

115), including two meta-analyses (

116,

117), have recently been published, we do not review the results of these studies in detail here. The consistent finding across these studies has been that cognitive-behavioral treatment is more effective than supportive counseling or standard care in reducing the severity of psychotic symptoms. Furthermore, studies that assess negative symptoms, such as social withdrawal and anhedonia, also report beneficial effects from cognitive-behavioral therapy on these symptoms.

Summary of research

The results of controlled research indicate that when illness management is conceptualized as a group of specific interventions, it is an evidence-based practice. The core components of illness management and the evidence supporting them can be summarized as follows. With respect to the more proximal outcomes, three studies (

15,

47,

48) found that psychoeducation was effective at increasing knowledge about mental illness, and a fourth (

49) did not. Similarly, all four studies of behavioral tailoring found that it was effective in improving the taking of medication as prescribed (

61,

64–

66). In terms of the more distal outcomes, all five studies of training in relapse prevention found that it reduced relapses and rehospitalizations (

76–

81), all four studies of teaching coping skills found that it reduced the severity of symptoms (

85–

88), and all eight studies of cognitive-behavioral treatment of persistent psychotic symptoms reported that it reduced the severity of psychotic symptoms (

89,

103,

107–

109,

112–

114). Although some studies of coping skills training differed in the symptoms they targeted, they all employed time-limited, cognitive-behavioral interventions. Thus psychoeducation, behavioral tailoring for medication, training in relapse prevention, and coping skills training employing cognitive-behavioral techniques are strongly supported components of illness management. Confidence in these findings is bolstered by the fact that the majority of the studies cited above were based on treatment manuals, and all except the studies by Schaub (

87) and Schaub and Mueser (

88) and the study by Tarrier and colleagues (

89,

112) were conducted by different groups of investigators.

The three studies of comprehensive illness management (

91–

94) suggest emerging evidence of the effectiveness of such programs. Improvements were seen in several important areas, such as social adjustment (

92,

93) and quality of life (

91). However, the differences between the components of the programs and their target outcomes preclude the drawing of any definitive conclusions about them.

Although the results of these studies support several components of illness management, the studies’ limitations should be acknowledged. First, most research has focused on persons with schizophrenia, which limits the findings’ generalizability. Second, few replications of standardized interventions have been published. Third, most research examines the effects of teaching illness management, with less attention paid to recovery. Although coping and symptom relief are important aspects of recovery (

27,

30,

42), little controlled research has examined the effect of interventions on the broader dimensions of recovery, such as developing hope, meaning, and a sense of purpose in one’s life.