Chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection affects 170 million people around the world (

1) and 2% of the U.S. population (

2,

3). It is the leading cause of chronic liver disease in the United States; left untreated, the liver disease can progress to cirrhosis, end-stage liver disease, and, rarely, hepatocellular carcinoma (

4). In 2005 more U.S. patients will die from HCV-induced liver disease than from HIV/AIDS (

5).

HCV is a neuropathic RNA-based virus from the Flaviviridae family (which includes, among others, the West Nile encephalitis virus) (

6). HCV has six different genotypes; however, only genotypes 1, 2, and 3 are common in the United States (

7). Up to 70% of U.S. HCV patients are infected with genotype 1, with genotypes 2 and 3 together accounting for the remainder (

8).

The natural history of HCV infection is highly variable (

9). Approximately 85% of persons infected with hepatitis C develop lifelong chronic infection (

10). Some 5%–20% of individuals with chronic HCV infection will develop cirrhosis over a span of 10–25 years. Alcohol use may accelerate the process toward cirrhosis (

4). Those who develop cirrhosis have an elevated risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma (a risk of 1%–4% per year), and up to 20% will develop end-stage liver disease (

11).

Well-established HCV risk factors include intravenous (IV) drug use, blood or blood product transfusions prior to 1992, and hemodialysis (

5). Targeted screening for HCV infection in patients with one or more of these risk factors has been recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and is clearly warranted (

12). However, evidence is beginning to emerge that other patient groups may also have an elevated risk of HCV infection (

13). These groups include non-IV drug users (

14–

16), patients with high-risk sexual practices (e.g., men having sex with men), and patients admitted to psychiatric hospitals (

17). Two distinct demographic groups that have an elevated prevalence of HCV infection and receive their medical care in specialized settings include patients followed at Department of Veterans Affairs hospitals (

18,

19) and incarcerated individuals (

20).

Although HCV is not considered a sexually transmitted disease, having multiple sexual partners is a risk factor (

5). Interestingly, sexual transmission of HCV is far less efficient than that of HIV (

2). The CDC reports that only 1.5% of partners of HCV carriers test positive for the disease, and the estimated risk of vertical transmission (mother to infant) is only 5% (

5). The transmission of HCV infection through tattooing and body piercing remains a controversial issue. The CDC’s view is that the data are insufficient to consider persons with tattoos and body piercings to have an elevated risk of HCV infection (

5). Table 1 lists the prevalence rates of HCV infection in populations of interest to psychiatrists and the percentage these groups represent in the general U.S. population.

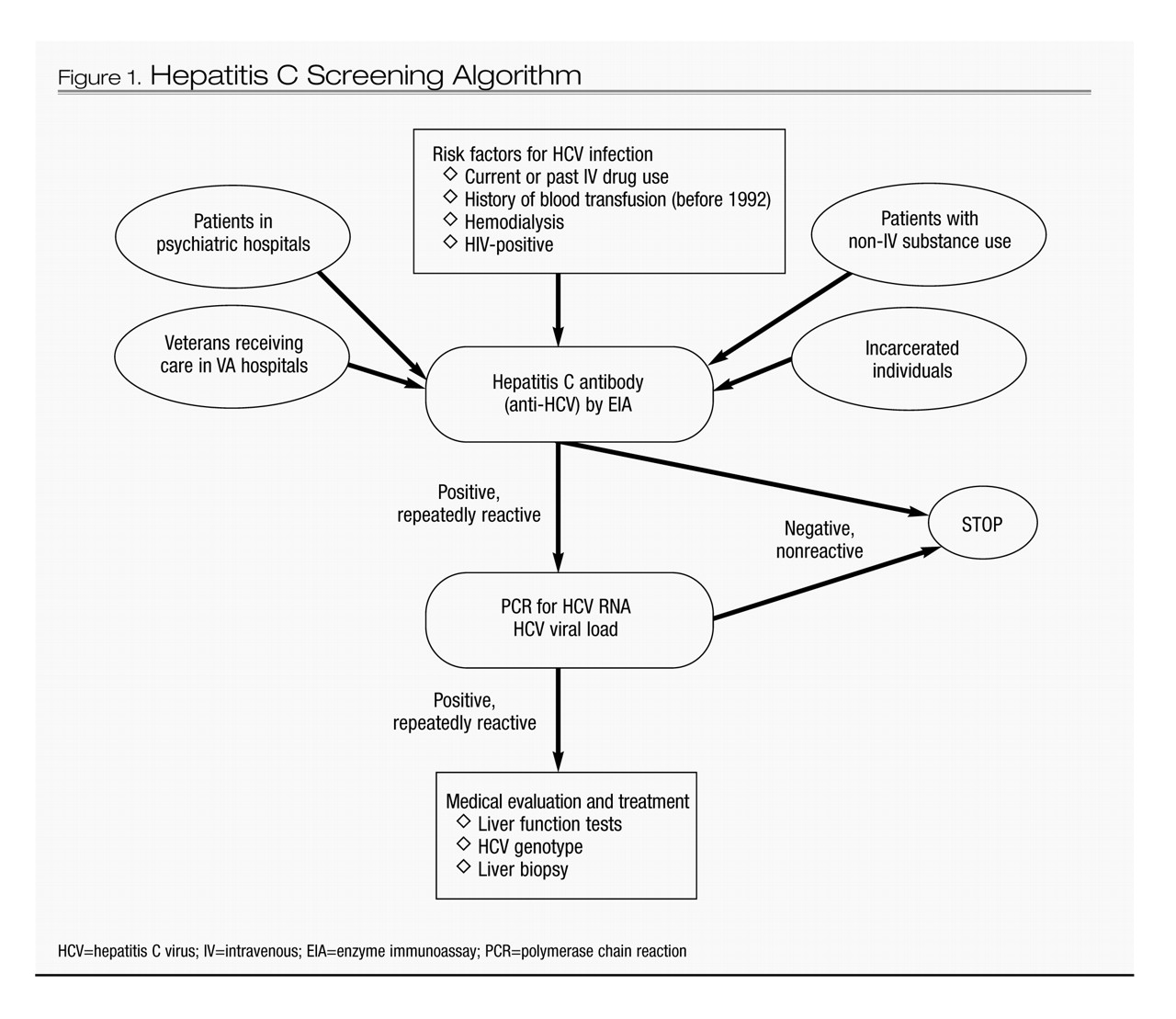

Hepatitis C screening

The optimal screening method for HCV infection is HCV antibody (anti-HCV) testing with a third-generation enzyme immunoassay (

21). In high-risk populations, anti-HCV has a sensitivity and specificity of 94%–96% (

21). Quantitative HCV RNA counts by polymerase chain reaction confirm HCV viremia and help in monitoring treatment response. HCV genotyping is used to guide the duration of treatment with therapies based on interferon-alpha (IFN) and as a prognostic indicator for response to IFN treatment (

2).

A negative anti-HCV test usually excludes HCV infection. However, psychiatrists should be aware of two instances in which a patient with a negative anti-HCV test can still have HCV infection (

10): immunocompromised individuals (e.g., patients with cancer or HIV/AIDS) and patients with acute HCV infection (i.e., less than 3 months) (

22). In both of these circumstances, serial HCV RNA measurements can confirm or exclude viremia (

23).

After confirmation of HCV infection, a liver biopsy is an important diagnostic procedure to assess the extent of HCV-induced liver disease (e.g., inflammation, fibrosis, and cirrhosis) and to inform the need for therapy. Another liver biopsy after IFN treatment can be used to ascertain whether any HCV-induced liver disease has resolved (

6). Figure 1 presents a simplified screening algorithm for HCV infection.

HCV posttest counseling

Patients who are found to be infected with HCV should be counseled on prevention of the spread of the virus to others (

5,

6). Table 2 lists the recommended points to be covered in posttest counseling for HCV. HIV testing should be offered, given that 5%–10% of patients with HCV are coinfected with HIV (

24). HCV can be transmitted through common household objects such as toothbrushes, shaving utensils, and other personal items. Although HCV infection has a low rate of sexual transmission (and particularly low rates of transmission among long-term monogamous partners), patients should still be advised to practice safe sex and use barrier protection to further reduce the risk of transmission of HCV and other sexually transmitted diseases. Alcohol use, even in moderation, has been shown to accelerate the progression of HCV-induced liver disease (

25). Consequently, HCV patients should be advised to eliminate any alcohol use (

26).

Rationale for screening and treatment of chronic HCV infection

Recent advances in the treatment of HCV and the introduction of pegylated interferons (PEG-IFNs) in combination with ribavirin have resulted in an improved sustained virologic response (SVR), defined as complete eradication of HCV with no detectable HCV viral load 6 months after IFN treatment is completed (

27). Among patients with HCV genotype 1, SVR rates are 50%–60%, and among patients with HCV genotypes 2 or 3, it is 80%–90% (

28). Several factors have been associated with reduced SVR rates: male gender; African American race; increased body mass index; advanced age (over 40 years); higher HCV RNA viral load; presence of liver fibrosis or cirrhosis; and HCV genotype 1 (

2). In patients infected with both HCV and HIV, the progression of liver disease (e.g., fibrosis and cirrhosis) is more rapid, and SVR rates in response to treatment are lower than in patients infected with only HCV (25%–35% overall) (

24).

Despite the intuitive value of HCV screening, posttest counseling, and antiviral treatment (

29), it remains to be demonstrated that these interventions will result in a reduction in morbidity and mortality from HCV infection. Consequently, the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force recently recommended against routine HCV screening for asymptomatic high-risk individuals (

30). Nonetheless, we contend that psychiatrists should continue to screen patients at risk of HCV and to provide infected patients with counseling, medical evaluation, and referral for IFN treatment (

9,

31).

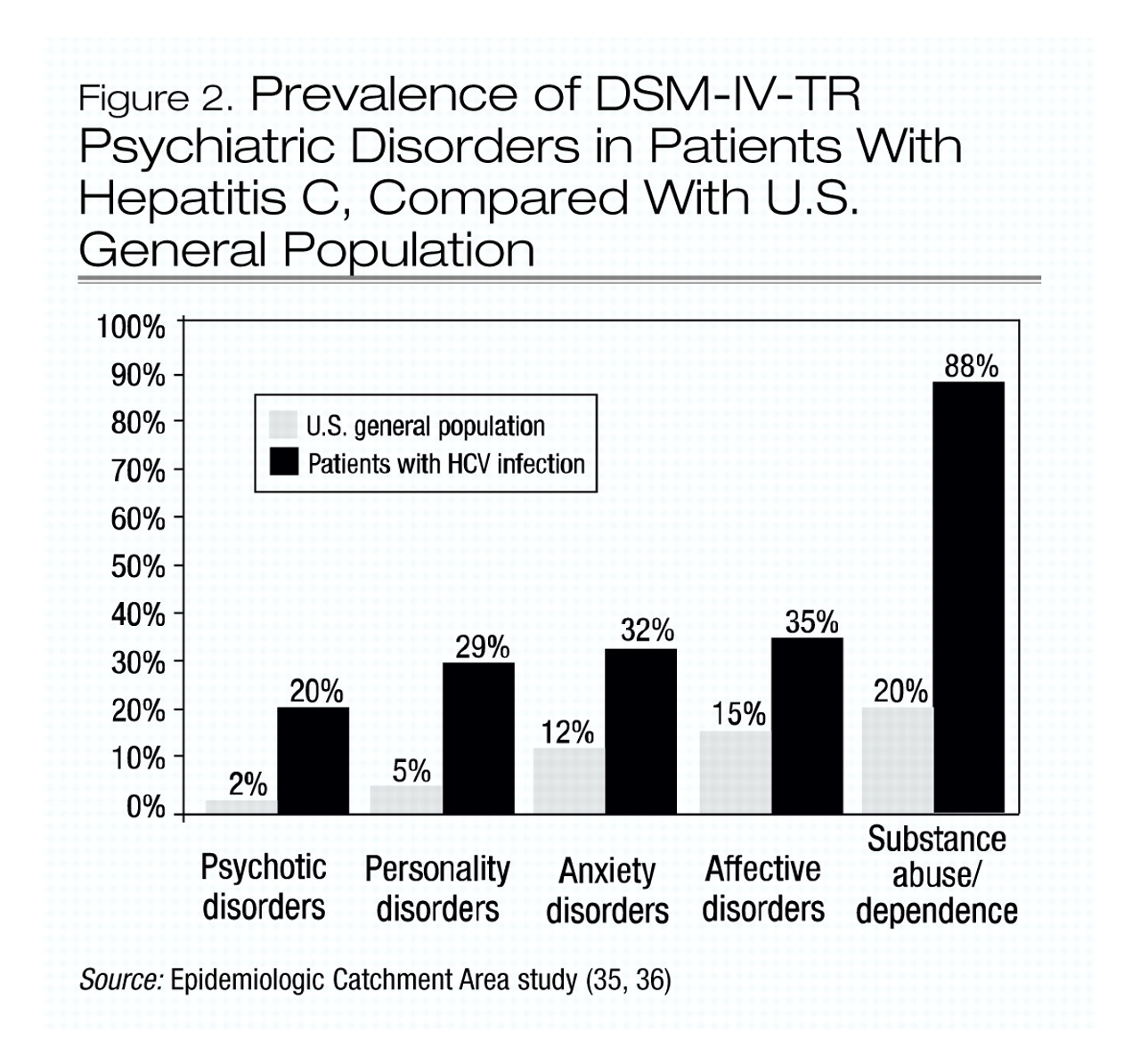

Psychiatric illness and hepatitis C

A growing body of evidence suggests that patients infected with HCV have a high prevalence of psychiatric disorders (

32–

34). At least 50% of patients infected with HCV suffer from one psychiatric illness, and the lifetime prevalence of psychotic, anxiety, affective, personality, and substance use disorders are all higher in the HCV-positive population (

32,

33) than in the general U.S. population (

35,

36) (Figure 2).

The extent to which psychiatric illness predisposes individuals to HCV infection and the extent to which HCV infection contributes to psychiatric illness are unknown. For some patients with preexisting mental illnesses such as psychotic or affective disorders, high-risk behavior (particularly the sharing of needles, syringes, or intranasal paraphernalia during drug use) clearly increases their risk of contracting HCV infection. However, for other patients, such as those with anxiety and substance use disorders, the distinction between cause and effect is less clear. In any case, for at least 20% of patients with HCV no clear, identifiable mode of transmission can be identified (

23).

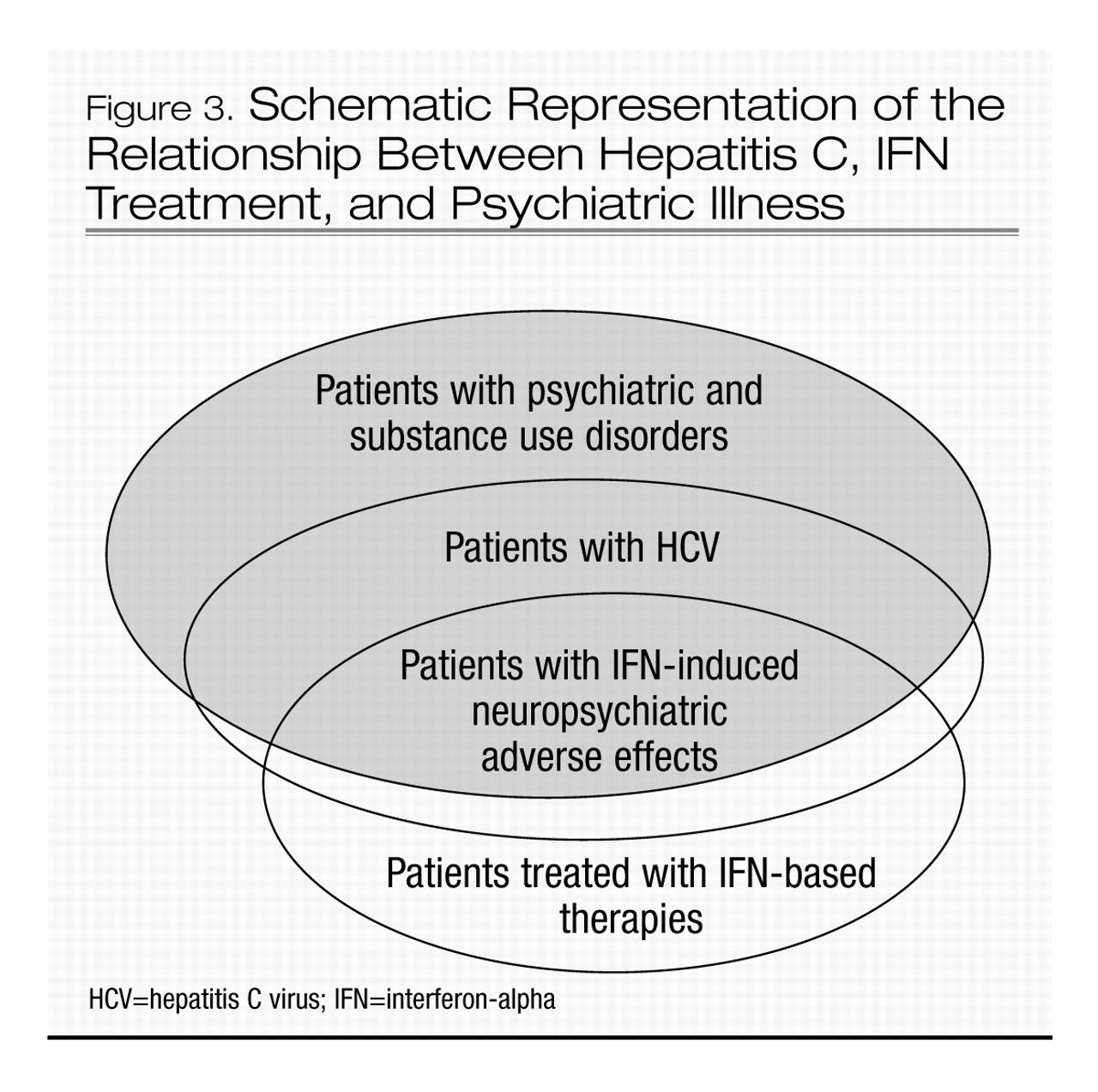

Hepatitis C in psychiatric populations

The prevalence of HCV among patients with severe mental illness is four to nine times (8%–18%) that of the general U.S. population (2%). The Five-Site Health and Risk Study found the prevalence of HCV infection among patients in psychiatric hospitals to be 18% (

11). In another study the prevalence of HCV infection among patients admitted to a state psychiatric hospital was found to be 8.5% (

14). Despite the association between HCV infection and psychiatric hospitalization, screening for HCV has not been routine practice in patients with psychiatric illness (

31). This patient population is at risk of contracting HCV by engaging in risky sexual behaviors (e.g., multiple partners, men having sex with men) and intranasal drug use but may not be forthcoming about these activities (

22). Therefore, the only reliable way to rule out HCV infection would be to use screening. For example, the CDC has recommended routine HCV screening of incarcerated individuals (

37). Routine screening is also recommended for all patients who are found to be infected with HIV (

22). Figure 3 shows a schematic representation of the relationship between HCV infection, treatment, and psychiatric illness.

Hepatitis C treatment and neuropsychiatric adverse effects

The therapeutic use of IFN is associated with frequent neuropsychiatric adverse effects, including affective, cognitive, and neurovegetative symptoms, that may compromise the management of HCV patients with and without a history of psychiatric illness (

38). HCV patients who are treated with IFN are at substantial risk of IFN-induced depression (the incidence is 20%–30%) (

39,

40) and other neuropsychiatric adverse effects that can reduce treatment adherence, require a reduction of the dose of the dose of IFN or discontinuation of IFN therapy (

41), and reduce the patient’s quality of life (

42). Nonetheless, recent studies (

39,

40) confirm that up to 30% of patients with preexisting psychiatric illness can complete their IFN treatment course without any significant worsening of their psychiatric symptoms. While one-third of patients undergoing IFN therapy experience depression (

43) and one-third suffer no neuropsychiatric symptoms (

39,

40,

44), the remaining 30%–40% experience of variety of neuropsychiatric adverse effects that can be managed if identified early. Such adverse effects include a wide range of somatic and neuropsychiatric symptoms, such as fatigue, amotivation, apathy, lack of concentration, irritability, anger, and perceptual, cognitive, and affective symptoms.

Several risk factors are thought to increase the probability of developing psychiatric comorbidity during IFN treatment (

45): a history of psychiatric illness (

40,

46); a history of substance abuse (

47); a family history of psychiatric illness (

48); and a history of suicidal ideation (

40). Although these factors are not well validated, they were used as exclusion criteria in several large HCV treatment clinical trials (

27,

49).

Although the incidence, phenomenology, psychiatric workup, and clinical management of preexisting and IFN-induced depression in HCV patients treated with IFN has been well described (

40), considerably less attention has been given to the interplay between HCV, other psychiatric disorders, and IFN (

40,

41). Table 3 summarizes the current knowledge about the use of psychotropic medications in patients with HCV undergoing IFN therapy.

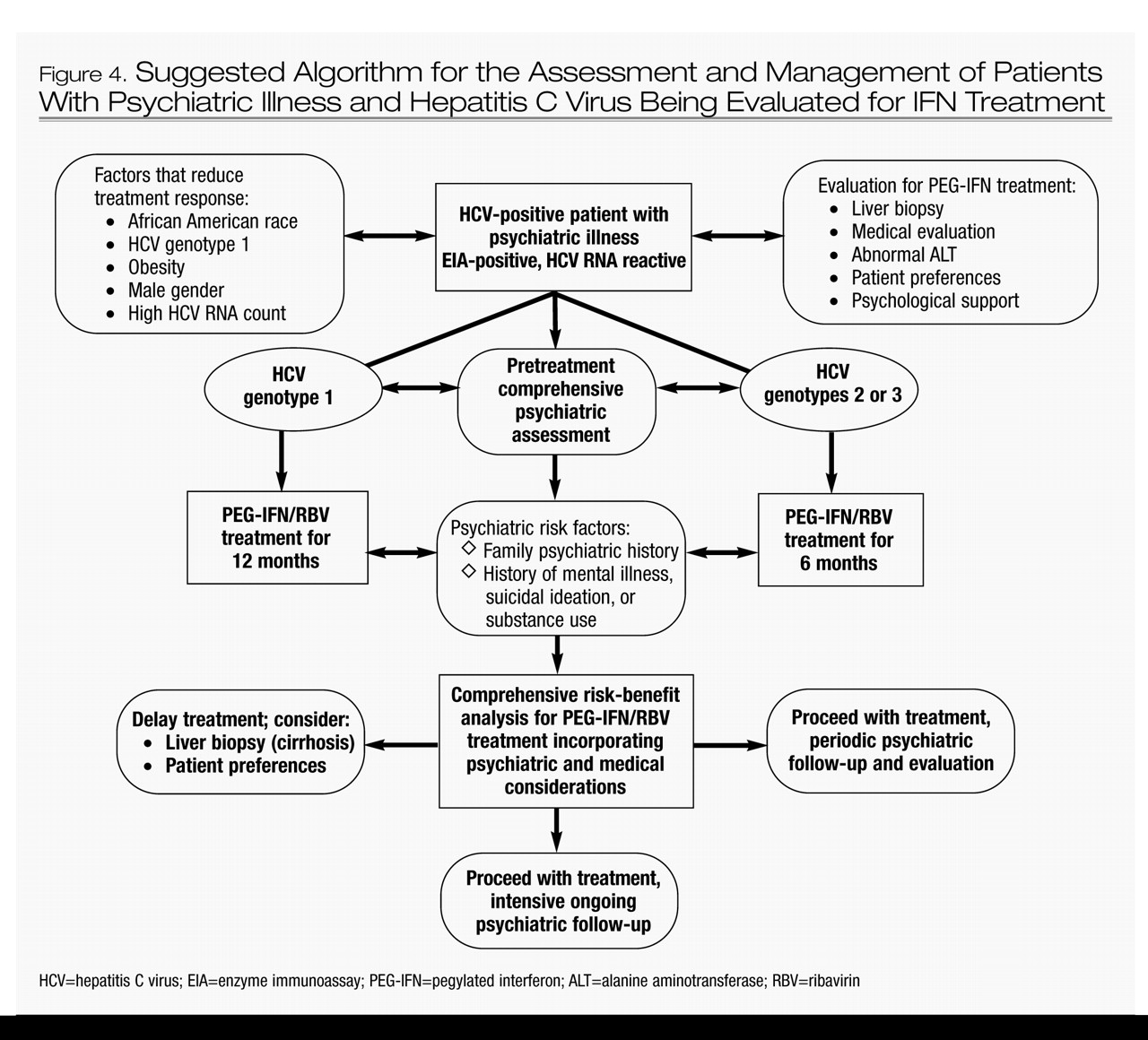

Should psychiatric patients with HCV be treated with IFN?

Clinicians remain hesitant to initiate IFN treatment in HCV patients with psychiatric illness because of concerns about precipitating or worsening psychiatric symptoms (

67). The practice of excluding patients with psychiatric illness from HCV treatment clinical trials is itself stigmatizing and can result in substantial morbidity and mortality for a vulnerable population (

68).

The management of patients with HCV infection who have psychiatric illness also poses unique challenges because psychotropic medications (e.g., antidepressants, antipsychotics, and mood stabilizers) are metabolized by the liver and can be hepatotoxic. The combination of HCV-induced liver disease, alcohol use, and psychotropic drugs may hasten the progression to cirrhosis. Patients with HCV and psychiatric illness who progress to cirrhosis and end-stage liver disease may also be less likely to receive a liver transplant because of the perceived difficulties they might have adhering to the rigorous posttransplant regimen.

With the exception of a few recent studies on the use of IFN in patients with substance use disorders (

47,

69,

70), there is relatively little information on the use of IFN in HCV patients with comorbid psychiatric illness such as affective, anxiety, and psychotic disorders (

71). The published SVR rates referred to earlier (

27,

49) may not be applicable to patients with HCV and psychiatric illness given the exclusion of patients with any history of psychiatric illness or substance abuse from most large HCV treatment trials. Consequently, there is a pressing need to develop improved therapeutic and management approaches to ensure that patients with HCV and comorbid psychiatric illness complete a full, uninterrupted course of IFN treatment.

The risk-benefit analysis for an HCV patient with evidence of liver cirrhosis and psychiatric illness may justify IFN treatment. Furthermore, patients with psychiatric illness who receive IFN treatment without achieving SVR may achieve normalization of liver function tests and improvement in liver pathology. However, long-term follow-up studies are needed to determine whether this benefit for IFN nonresponders would translate into a reduction in the incidence of liver cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma. If such a benefit is confirmed, it would strengthen the argument for treating patients with HCV and psychiatric illness with IFN. Figure 4 presents a comprehensive risk-benefit assessment process for patients with HCV and psychiatric illness.

Evidence-based patient selection is paramount when attempting to minimize the morbidity and mortality associated with IFN treatment of HCV patients with comorbid psychiatric illnesses. Despite the absence of a consensus on when IFN treatment should be withheld (because of the low estimated likelihood of SVR and/or the high probability of associated psychiatric morbidity), clinicians must undertake an individualized and balanced risk-benefit analysis for each patient before offering IFN treatment, incorporating not only factors specific to HCV disease and the potential for psychiatric complications but also the patient’s preferences and the psychosocial support available.