Two diagnostic classification manuals are commonly used to specify diagnostic criteria for disorders of primary EDS. DSM-IV-TR (

American Psychiatric Association 2000) subcategorizes these disorders into

narcolepsy and

primary hypersomnia; the latter includes all non-narcolepsy forms of primary EDS. The

International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD;

American Sleep Disorders Association 1997) subcategorizes primary EDS into narcolepsy, idiopathic hypersomnia, recurrent hypersomnia, and posttraumatic hypersomnia. We have selected the ICSD format to organize this review, but we suggest the expansion of the posttraumatic category to include CNS pathology in addition to trauma.

As suggested by both DSM-IV-TR and ICSD, several entities may be regarded as primary disorders of EDS. Narcolepsy, the best known and the most completely understood disorder of this group, will be considered at greater length; other clinical syndromes will be reviewed more briefly. Patients with these CNS-mediated EDS syndromes commonly receive a misdiagnosis of a mood disorder and are treated with antidepressant therapy.

Narcolepsy

Narcolepsy is a syndrome of unknown etiology characterized by a profound degree of EDS. Narcolepsy usually occurs in association with cataplexy and other symptoms and signs, including hypnagogic or hypnopompic hallucinations, sleep paralysis, automatic behavior, and disrupted nocturnal sleep (

American Sleep Disorders Association 1997). Symptoms most often begin during adolescence or young adulthood. However, narcolepsy may also occur earlier in childhood or not until the third or fourth decade of life. The impact of narcolepsy on quality of life is equal to that of other chronic neurologic disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease (

Beusterien et al. 1999). No symptom or sign of narcolepsy is specific to narcolepsy; even cataplexy unrelated to narcolepsy occurs, rarely, either as an isolated symptom or in conjunction with other conditions. Unfortunately, the average duration from symptom onset to the conferring of an accurate diagnosis is greater than 10 years. This substantial delay in diagnosis is largely due to clinicians’ lack of education about and experience with this disorder.

Symptoms of narcolepsy include the following:

•

Sleepiness or excessive daytime sleepiness. The EDS of narcolepsy presents as an increased propensity to fall asleep, nod, or doze easily in relaxed or sedentary situations, or a need to exert extra effort to avoid sleeping in these situations. Additionally, irresistible or overwhelming urges to sleep commonly occur from time to time during wakeful periods in untreated patients. These “sleep attacks” are not instantaneous lapses into sleep, as is often thought by the general public, but represent episodes of profound sleepiness similar to that caused by severe sleep deprivation or other severe sleep disorders. Many but not all patients with narcolepsy find that brief naps and longer sleep periods can be temporarily restorative or refreshing. This contrasts with the response to naps or sleep observed in idiopathic hypersomnia, wherein sleep of any duration is rarely restorative. In addition to frank sleepiness, the excessive daytime sleepiness of narcolepsy can cause or contribute to related symptoms, including poor memory, reduced concentration or attention, and irritability.

•

Cataplexy. Cataplexy is the partial or complete loss of bilateral voluntary muscle tone in response to strong emotion. The reduced muscle tone may be minimal, occur in a few muscle groups, and cause minimal symptoms such as bilateral ptosis, head drooping, slurred speech, or dropping things from the hand. On the other hand, it may be so severe that total body paralysis occurs, resulting in complete collapse. Cataplectic events usually last from a few seconds to 2 or 3 minutes, but they occasionally continue longer (

Honda 1988). The patient is usually alert and oriented during the event despite the inability to respond; thus, cataplectic episodes are distinct from sleep episodes. Positive emotions such as laughter trigger cataplexy more commonly than negative emotions. However, any strong emotion is a potential trigger (

Gelb et al. 1994). Startling stimuli, stress, physical fatigue, and sleepiness may also be important triggers or factors that exacerbate cataplexy.

According to epidemiologic studies, cataplexy is found in 60%–100% of patients with narcolepsy. The onset of cataplexy is most frequently simultaneous with or within a few months of the onset of EDS, but in some cases cataplexy may not develop until many years after initial onset of EDS (

Honda 1988).

•

Hypnagogic or hypnopompic hallucinations. These phenomena are visual (most common), tactile, auditory, or multisensory events, usually brief but occasionally continuing for a few minutes, that occur at the transition from wakeful-ness to sleep (hypnagogic) or from sleep to wakefulness (hypnopompic). Hallucinations may contain elements of dream sleep and consciousness combined, and they are often bizarre or disturbing to patients. Occasionally, patients who experience these episodes are misdiagnosed with a psychotic syndrome and inappropriately treated with antipsychotic medications.

•

Sleep paralysis. Sleep paralysis is the inability to move, lasting from a few seconds to minutes, during the transition from sleep to wakeful-ness or from wakefulness to sleep. Episodes of sleep paralysis may alarm patients, particularly those who experience the sensation of being unable to breathe. Although accessory respiratory muscles may not be active during these episodes, diaphragmatic activity continues and air exchange remains adequate.

•

Other symptoms. Other commonly reported symptoms in narcolepsy include automatic behavior—absent-minded behavior or speech that is often nonsensical and that the patient does not remember because of extreme sleepiness. In addition, many individuals with narcolepsy report fragmented nocturnal sleep—that is, frequent awakenings during the night.

Hypnagogic hallucinations, sleep paralysis, and automatic behavior are not specific to narcolepsy and may occur in other sleep disorders, as well as in healthy individuals. These symptoms are, however, far more common and occur with much greater frequency in narcolepsy.

The following tools are available for the evaluation of narcolepsy:

•

Polysomnography. Nocturnal polysomnography (PSG) is not essential in the diagnostic workup when straightforward cataplexy accompanies EDS. However, it remains an important part of the evaluation process, primarily to exclude other conditions that occur in narcolepsy at a higher than normal rate, such as obstructive sleep apnea (see Chapter 3, “Sleep Apnea”), PLMD (see Chapter 5, “Restless Legs Syndrome”), and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behavior disorder. These conditions may contribute to the sleepiness or nocturnal sleep disruption the patient may be experiencing (

Overeem et al. 2001). Additionally, individuals with narcolepsy may demonstrate sleep-onset REM periods during nocturnal PSG. Normally, nocturnal sleep begins with a long period of non–rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep (see Chapter 1, “Introduction”).

•

Daytime sleep studies. Daytime nap studies, in the form of the multiple sleep latency test (MSLT), usually demonstrate substantially reduced sleep latency coupled with sleep-onset REM periods (SOREMPs) in patients with narcolepsy. This test subjects the patient to four or five 20-minute nap opportunities, under PSG monitoring, at 2-hour intervals across the morning and afternoon. During testing, the patient is in bed in a dark room and is instructed to try to fall asleep. Average MSLT sleep latencies for

normal control subjects are 12–15 minutes, but latencies for patients with narcolepsy with cataplexy average approximately 2–4 minutes (US

Xyrem in Narcolepsy Multi-center Study Group 2002); however, there can be substantial variability across patients and within patients. SOREMPs are not specific for narcolepsy, but the occurrence of two or more of these events during the MSLT, in the setting of objective marked sleepiness and without another explanation for their occurrence (e.g., sleep deprivation, REM-suppressant medication rebound, altered sleep schedule, obstructive sleep apnea, or delayed sleep phase syndrome), is suggestive of narcolepsy. The presence of two or more SOREMPs can be found in a subset of patients with any of the other conditions just mentioned. These conditions are far more prevalent than narcolepsy. Therefore, the specificity for narcolepsy of two or more SOREMPs on the MSLT is low, but most patients with straightforward narcolepsy will manifest this finding.

•

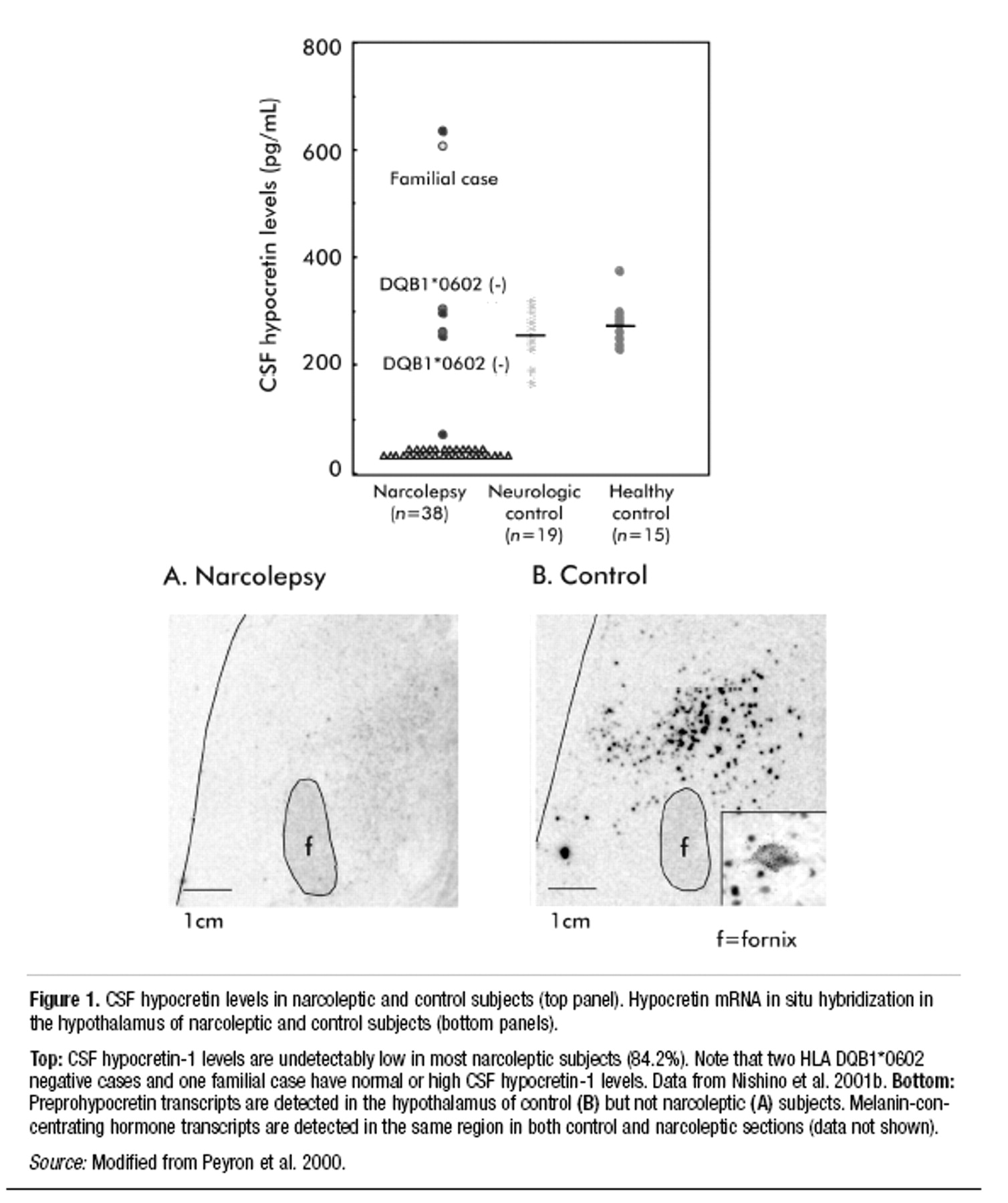

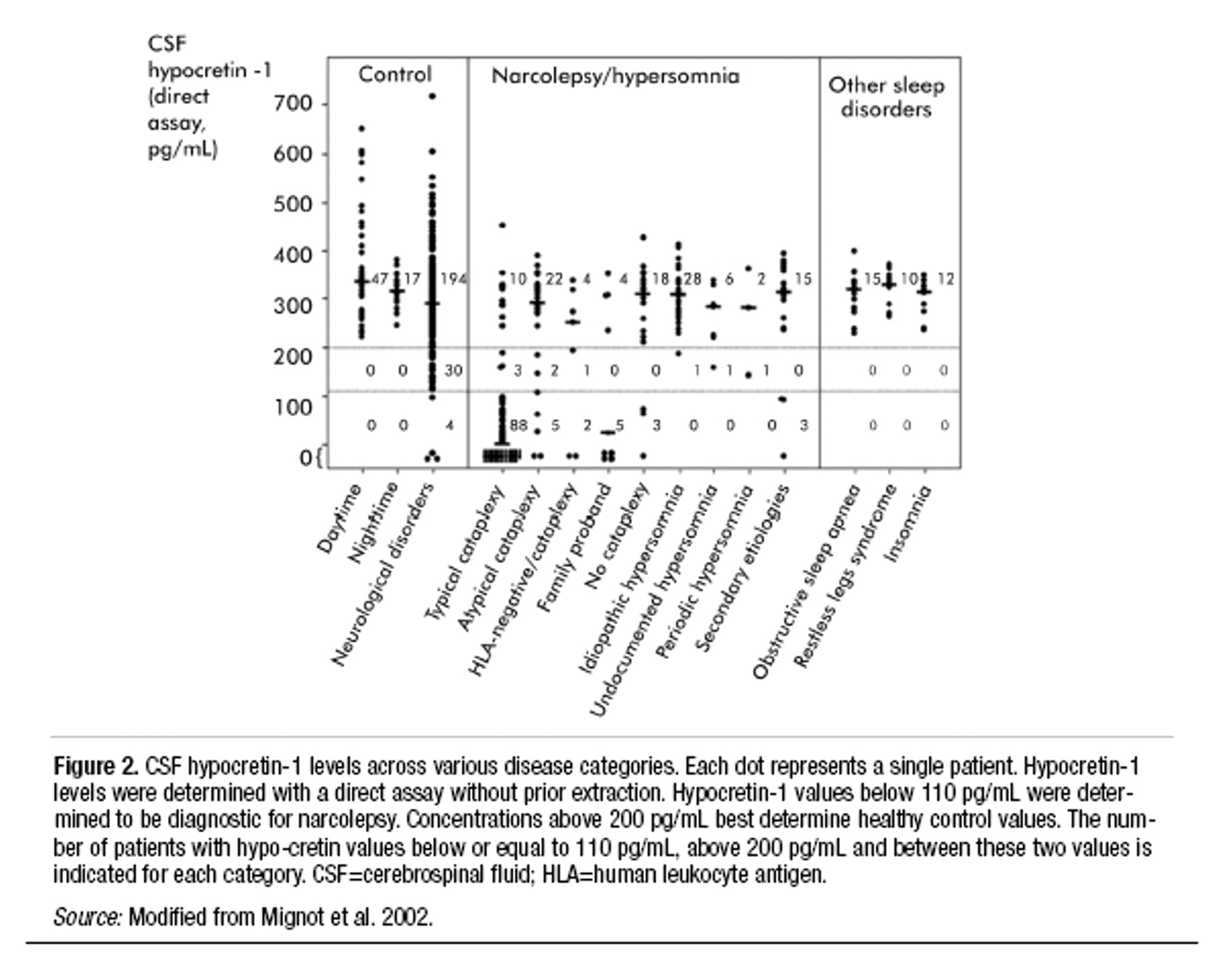

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) hypocretin assessment. As discussed below in the section on the pathophysiology of narcolepsy, many, but not all, patients with narcolepsy have very low or undetectable levels of the peptide neurotransmitter hypocretin in the CSF (

Nishino et al. 2000b;

Mignot et al. 2002). Such low levels of CSF hypocretin are not specific for narcolepsy. However, when used to assess patients for narcolepsy, low CSF hypocretin appears to be a much more specific test than the MSLT. Whether this test is more sensitive than the MSLT has yet to be determined.

•

Histocompatibility human leukocyte antigen (HLA) testing. A very strong but incomplete correlation exists between narcolepsy (with cataplexy) and the HLA subtype DQB1* 0602. However, this subtype is also very common in the general population (occurring in about 20% in the United States) and is not at all specific nor sensitive for narcolepsy (

Mignot 1998). HLA testing is therefore not useful in confirming or excluding the diagnosis of narcolepsy, and in fact may lead a clinician to inappropriate diagnostic conclusions.

Idiopathic hypersomnia

Idiopathic hypersomnia (previously labeled

idiopathic CNS hypersomnia) is an incompletely defined disorder characterized by EDS. This diagnosis has been used as a nosologic haven for classifying individuals with excessive somnolence but without the classic features of narcolepsy or another disorder known to cause EDS, such as sleep apnea. Without doubt, many patients have received diagnoses of idiopathic hypersomnia who actually had other disorders, such as narcolepsy without cataplexy, delayed sleep phase syndrome, or upper airway resistance syndrome, a subtle variant of the obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (

Guilleminault et al. 1993).

Roth (1976) described monosymptomatic and polysymptomatic forms of idiopathic hypersomnia, the former characterized by EDS alone and the latter characterized by EDS, prolonged nocturnal sleep time, and marked difficulty with awakening. Others have suggested that the category of idiopathic hypersomnia is heterogeneous, including individuals with EDS with or without one or more of the other features of Roth’s polysymptomatic form (

Aldrich 1996).

Idiopathic hypersomnia is believed to be less common than narcolepsy; estimation of prevalence, however, is elusive because strict diagnostic criteria are lacking and no specific biological marker has been identified. Typically, onset of symptoms occurs in adolescence or early adulthood. Symptoms generally persist for life, although a few patients with idiopathic hypersomnia have improved over time or attained complete remission of symptoms (

Bassetti and Aldrich 1997;

Billiard and Dauvilliers 2001;

Bruck and Parkes 1996). The etiology of the disorder is not known, but viral illnesses, including Guillain-Barré syndrome, hepatitis, mononucleosis, and atypical viral pneumonia, may herald the onset of sleepiness in a subset of patients. EDS may occur as part of the acute illness, but it persists after the other symptoms subside. Familial cases are known to occur, with increased frequency of HLA-Cw2 and HLA-DR11 (

Montplaisir and Poirier 1988). Some of these patients have associated symptoms suggesting autonomic nervous system dysfunction, including orthostatic hypotension, syncope, vascular headaches, and peripheral vascular complaints. Most patients with idiopathic hypersomnia have neither a family history nor an obvious associated viral illness. Little is known about the pathophysiology of idiopathic hypersomnia. No animal model is available for study. Neurochemical studies examining CSF have suggested that patients with idiopathic hypersomnia may have altered noradrenergic system function (

Faull et al. 1983,

1986;

Montplaisir et al. 1982).

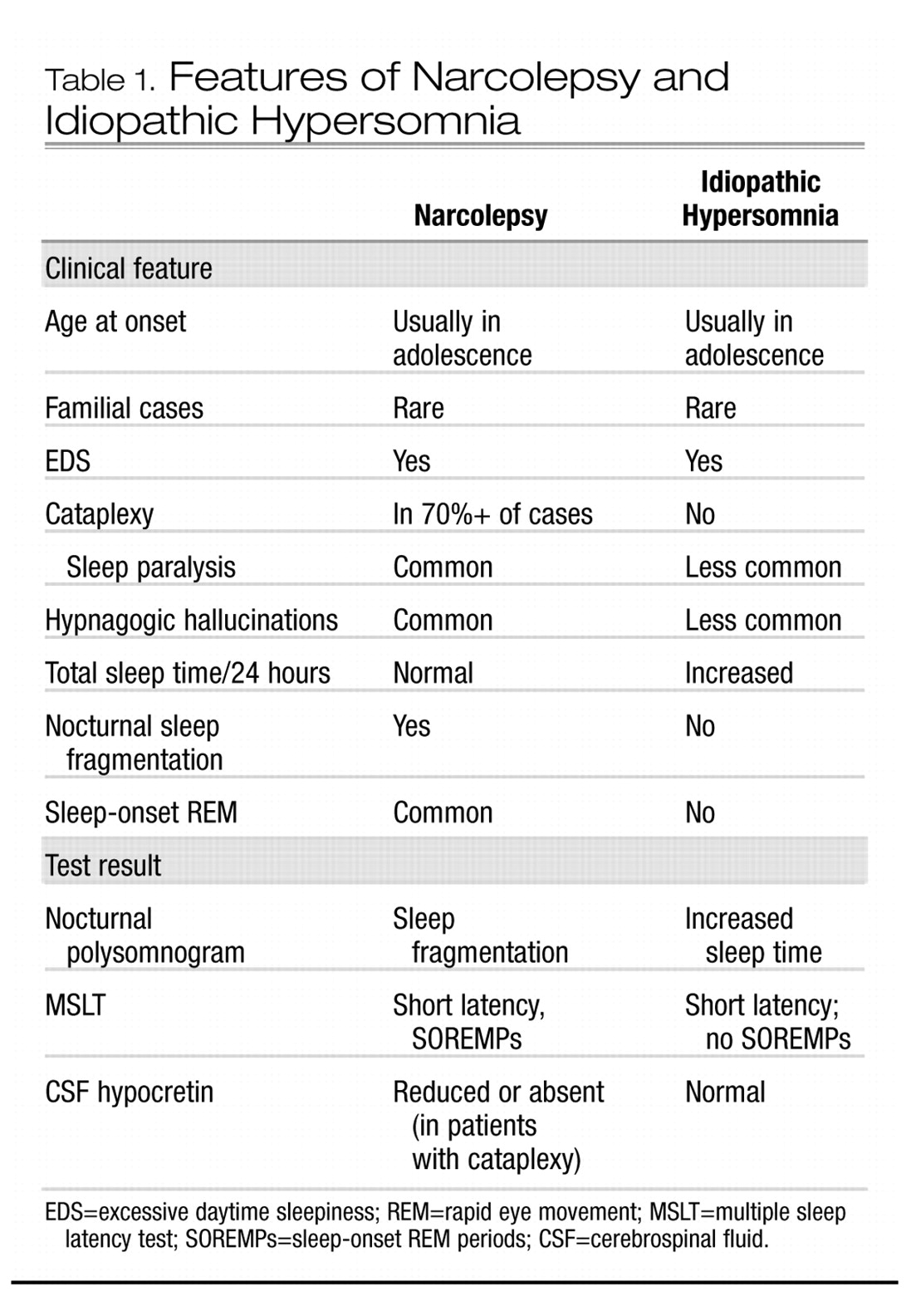

The clinical picture of idiopathic hypersomnia varies among individual patients. The disorder may be mistaken for narcolepsy if a careful history is not taken. The two disorders share several common features, including similar age of onset, lifelong persistence after onset, EDS as the primary symptom, and familial clustering of some cases. However, essential differences between the disorders become apparent in the history and in diagnostic studies (see Table 1). Patients with idiopathic CNS hypersomnia present with EDS, but with neither cataplexy (although some patients have episodes of sleep paralysis or hypnagogic hallucinations) nor significant nocturnal sleep disruption (

Billiard and Dauvilliers 2001). They complain of daytime sleepiness that interferes with normal activities. Occupational and social functioning may be severely affected by sleepiness. Nocturnal sleep time tends to be long, and patients are usually difficult to awaken in the morning, becoming irritable or even abusive in response to the efforts of others to rouse them. In some patients, this difficulty may be substantial and may include confusion, disorientation, and poor motor coordination, a condition sometimes termed “sleep drunkenness” (

Roth et al. 1972). These patients often take naps, which may be prolonged but, in contrast to naps in narcolepsy, are usually nonrefreshing. No amount of sleep ameliorates the EDS. “Microsleeps,” with or without automatic behavior, may occur throughout the day.

Polysomnographic studies of patients with idiopathic CNS hypersomnia usually reveal shortened initial sleep latency, increased total sleep time, and normal sleep architecture, in contrast to narcoleptic patients, who exhibit significant sleep fragmentation. Using quantitative electroencephalography,

Sforza et al. (2000) found reduced sleep pressure, as evidenced by decreased slow-wave activity during the first two NREM episodes of nocturnal sleep, in patients with idiopathic hypersomnia. Mean sleep latency on MSLT is usually reduced, often in the 8–10-minute range but sometimes dramatically shorter. Also in contrast to narcolepsy, SOREMPs are not typically seen.

As with narcolepsy, other disorders producing EDS (such as insufficient sleep, sleep-related breathing disorders, PLMD, other sleep-fragmenting disorders, psychiatric diseases, and circadian rhythm disorders) must be ruled out before the diagnosis of idiopathic hypersomnia is made.