The central role of hopelessness in the development of suicidal ideation has been supported by empirical research (

4–

7). Wetzel et al. (

8) reviewed studies addressing the relationships among depression, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation and concluded that the preponderant evidence supported the linkage of hopelessness and suicide intent. In a 10-year prospective follow-up study of 165 patients hospitalized with suicidal ideation, Beck et al. (

9) reported that hopelessness was predictive of actual suicide. Of the 11 patients who eventually committed suicide, 10 (90.9%) had Beck Hopelessness Scale (

10) scores of 9 or greater. Only one patient (9.1%) who eventually committed suicide had a score lower than 9. The mean Beck hopelessness score was significantly higher in the patients who committed suicide (mean±SD=13.27±4.43) than in the patients who did not (mean±SD=8.94±6.05) (t=2.33, df=163, p<0.05). Furthermore, length of follow-up was not related to detecting more eventual suicides.

Results

Follow-up

Patients were followed up from date of evaluation until December 3 1,1985. The mean±SD length of follow-up was 43.00±20.71 months (range=8.20–89.57 months). Of the 1,958 patients who were evaluated (but not necessarily treated) at the clinic, 31 (1.6%) died during the follow-up period. Of these 31 patients, 17 (54.8%) committed suicide and 12 (38.7%) died from natural causes; in two cases (6.5%) the official completing the death certificate could not classify the cause of death as natural, accidental, suicide, or homicide. Cases in this last category were dropped from all further analyses.

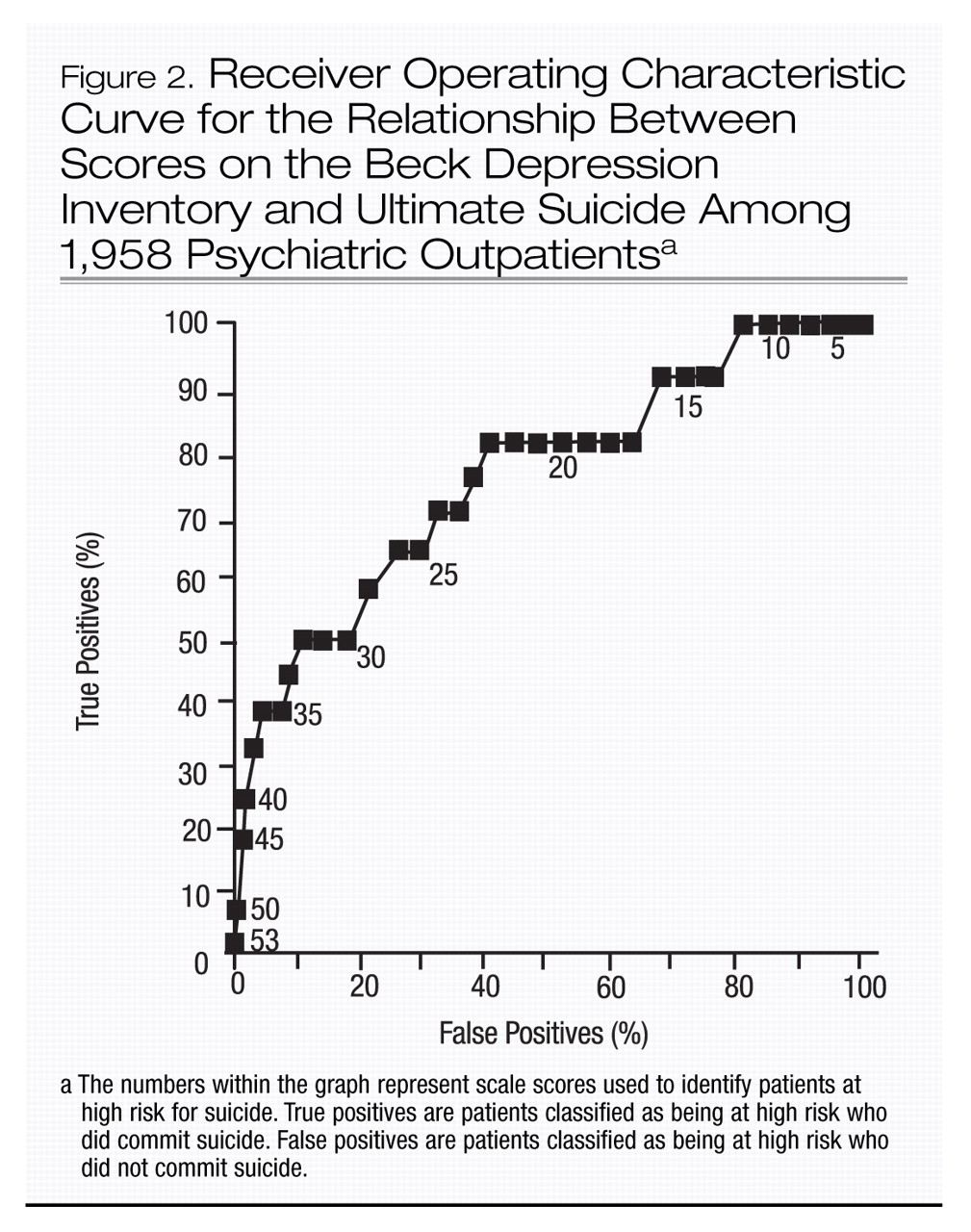

At intake, the patients who eventually committed suicide ranged in age from 18 to 59 years (mean±SD=40.35±11.61). Nine (52.9%) of these patients were men and eight (47.1 %) were women. Thirteen received diagnoses of recurrent major depression (or chronic depressive neurosis), three diagnoses of bipolar disorder, and one a diagnosis of adjustment disorder with depressed mood.

Ten (58.8%) of the 17 patients who committed suicide received cognitive therapy, whereas seven (41.2%) were just evaluated for cognitive therapy and did not enter therapy. The number of visits ranged from one to 25. Only one patient (5.9%) was in treatment at the time of his suicide. Eight (47.1%) had made at least one prior suicide attempt, and five (29.4%) had received an alcohol-related diagnosis.

Group differences

We examined the mean ages and Beck hopelessness and depression scores of those who committed suicide, those who died of natural causes, and living patients. In the case of one of the patients who committed suicide, who began treatment at the center on two separate occasions, self-report scores were available for the initial admission, which occurred in 1976, predating the period under study; consequently, the scores from the initial admission were used. Predictably, the patients who eventually died of natural causes were older as a group (mean±SD age=48.08±18.82 years) than the patients who committed suicide (40.35±11.61 years) and the living patients (36.01±12.31 years) (F=6.71, df=1, 1,955, p<0.001). As hypothesized, patients who committed suicide had higher scores on both the Beck Hopelessness Scale and the Beck Depression Inventory (mean±SD=15.29±4.47 and 30.59±11.52, respectively) than the patients who died of natural causes (7.33±5.21 and 20.92±8.64) and the living patients (9.98±5.42 and 20.14±9.88) (hopelessness scale: F=9.60, df=2, 1,955, p<0.001; depression inventory: F=9.44, df=2, 1,955, p<0.001).

The Beck Hopelessness and Depression scales

Determination of optimal cutoff scores.

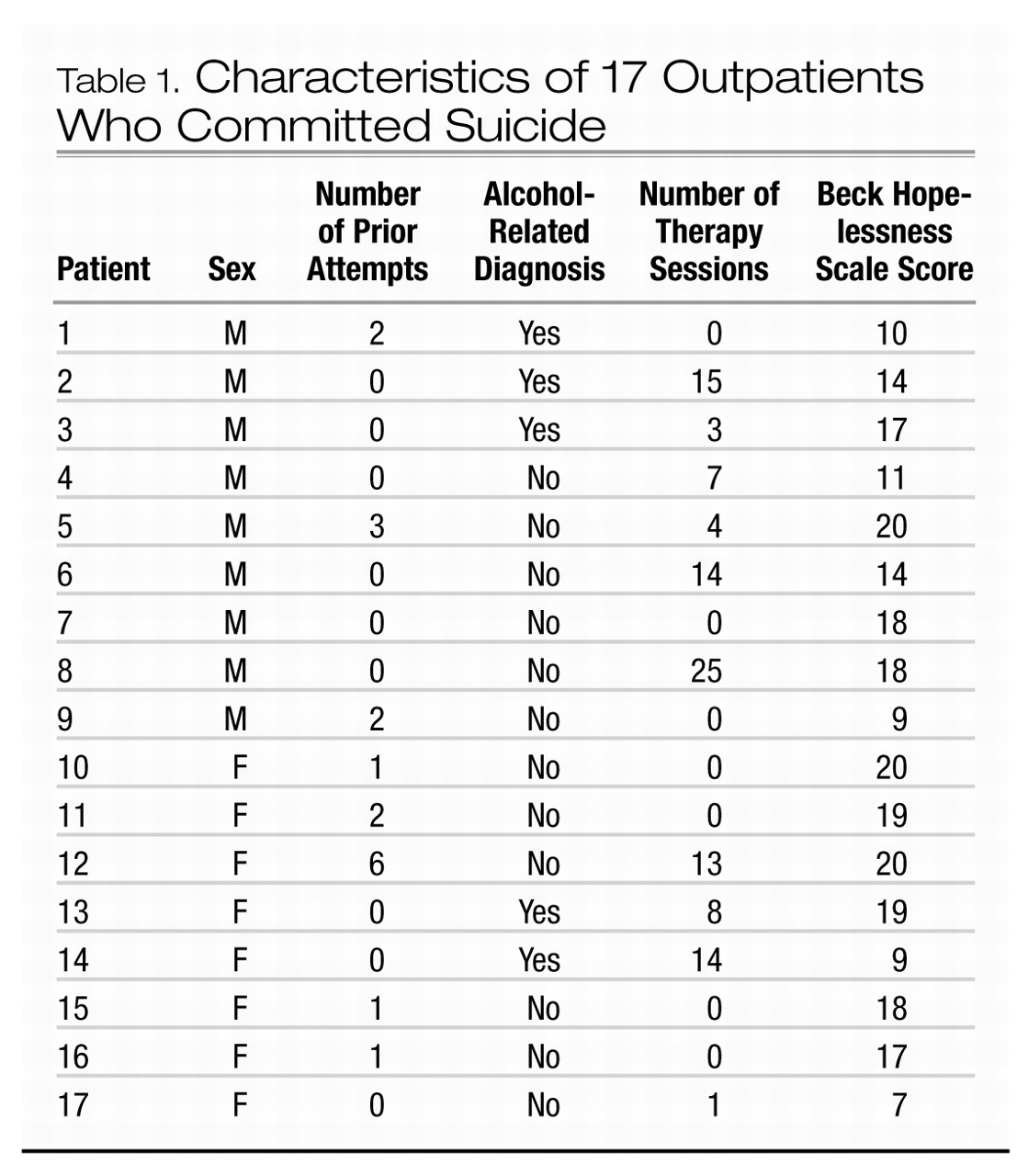

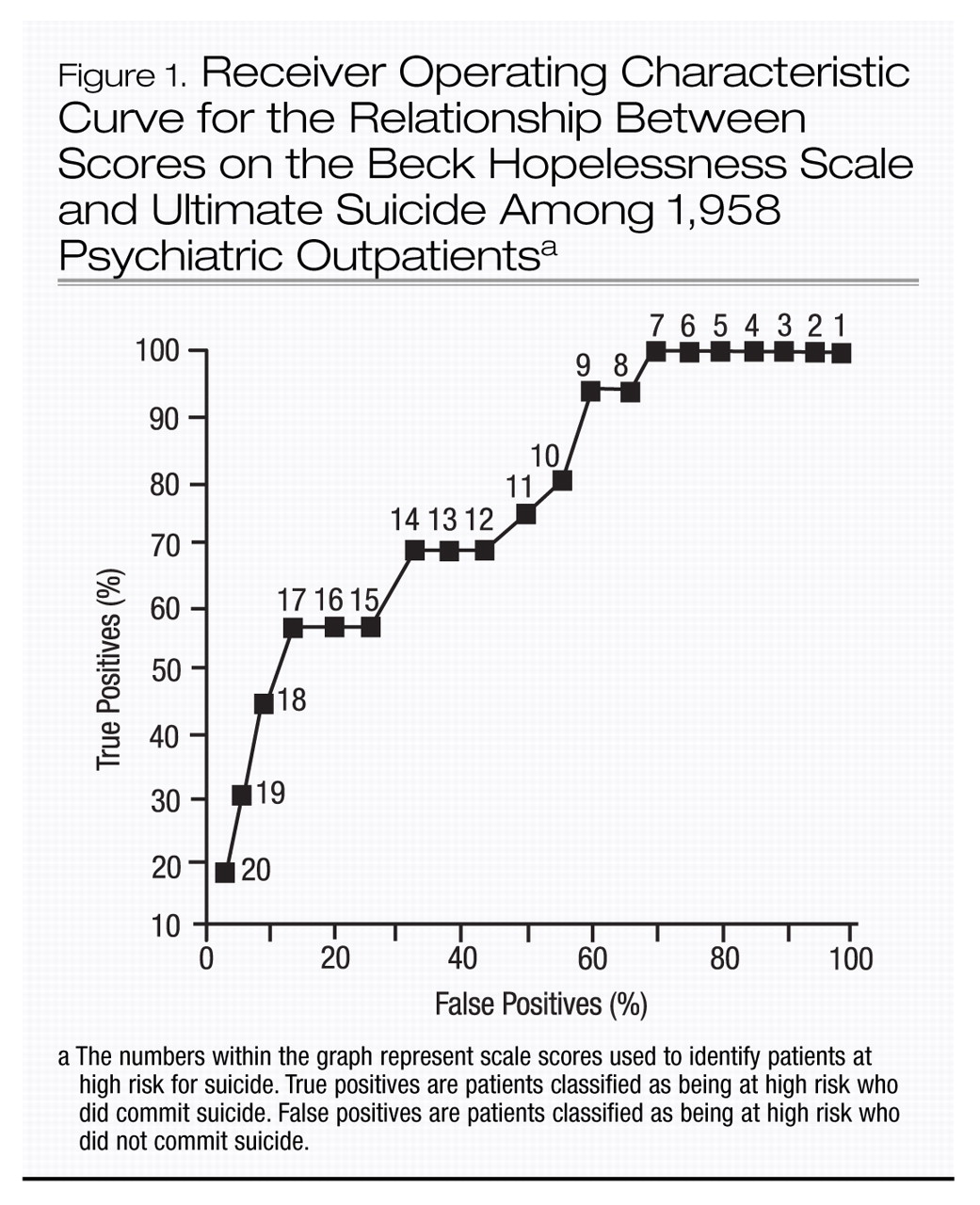

Optimal cutting scores for the two Beck scales were derived by applying a technique drawn from signal detection theory, the receiver operating characteristic curve (

14). To construct such a curve, the percentage of positive responses in the presence of a signal (“hits” or true positives) is plotted against the percentage of positive responses in the absence of a signal (“false alarms” or false positives) for successive stimulus intensities. In terms of the present study, completed suicide is the signal and test score is the stimulus level.

Receiver operating characteristic curves for the Beck Hopelessness Scale and the Beck Depression Inventory are shown in Figures 1 and 2. For situations in which maximizing sensitivity (the probability of suicide in subjects who are classified as at high risk by their test scores) and minimizing specificity (the probability of no suicide in subjects who are classified as at low risk by their test scores) are equally important, the optimal cutting score occurs at the point of furthest displacement of the curve. Because false negatives represent a loss of life, sensitivity is paramount in suicide prediction. The cutting score that maximizes sensitivity (at the expense of specificity) occurs where the distance from the vertical axis is minimized, while the distance to the horizontal axis is maximized. A Beck hopelessness score of 9 and a Beck depression score of 23 satisfy this criterion.

Predictive validity.

The Beck hopelessness score of 9 or above defined a group (N=1,161) that included 16 (94.1%) of the 17 patients who committed suicide. The Beck depression cutoff score of 23 or above defined a smaller group (N=743) that included 13 (76.5%) of the patients who committed suicide. Although the Beck depression inventory had higher specificity (62.4%) than the Beck Hopelessness Scale (41.0%), the hopelessness scale had higher sensitivity (94.1%) than the depression inventory (76.5%). In addition, the high-risk group defined by the hopelessness scale (N=16 of 1,161) was 11.0 times more likely to commit suicide than the low-risk group (N=1 of 797); this was more than double the relative rate for the high- and low-risk groups defined by the depression inventory (N=13 of 743 and 4 of 1,215; odds ratio=5.3).

Sensitivity to other risk factors.

We also wished to compare the 94.1% sensitivity rate found for the Beck Hopelessness Scale, by using a cutoff score of 9 or above against the outpatient sensitivity rates for selected suicide risk factors that had been previously investigated in the inpatient study of the relationship between hopelessness to ultimate suicide (

9). The risk factors included gender, previous suicide attempts, and a diagnosis of alcoholism. Of the 17 patients who eventually committed suicide (table 1), nine were men; the sensitivity rate for maleness was thus 52.9%. With respect to a history of previous suicide attempts, eight of the 17 patients who committed suicide had made at least one prior attempt; the sensitivity rate was 47.1 %. Five of the 17 patients had received an alcohol-related diagnosis; the sensitivity rate for alcoholism was 29.4%. Obviously, the sensitivity rates for the three characteristics were substantially lower than that for the Beck Hopelessness Scale when a cutoff score of 9 or above was used (94.1%).

To gauge the specificity rates with respect to the previous characteristics, a subsample of 17 of the patients who did not commit suicide was chosen at random. In this subsample there were 10 men; the specificity rate for maleness was 41.2%. None of these patients had made a prior attempt or had a diagnosis of alcoholism; the specificity rates were both 100%. Therefore, the specificity rate for these past history variables was maximal, but the sensitivity rates were low compared to those of the Beck Hopelessness Scale and the Beck Depression Inventory.

Discussion

The present study was conducted specifically to ascertain whether level of hopelessness would be as predictive of eventual suicide in outpatients as it had been in the previously reported study of hospitalized patients with suicidal ideation (

9). In the present study, patients who ultimately committed suicide scored significantly higher on both the Beck Hopelessness Scale and the Beck Depression Inventory than did patients who did not commit suicide and patients who died from natural causes. Moreover, an optimal cutting score on the hopelessness scale identified a group that was 11 times more likely to commit suicide than the low-risk group, and twice as likely to commit suicide as the high-risk and low-risk groups defined by the Beck Depression Inventory.

The present results replicate the earlier study of psychiatric inpatients by Beck et al. (

9), which found a similar prediction rate with the same Beck Hopelessness Scale cutoff score of 9 or above. Together, these studies support the growing body of research which suggests that hopelessness is more directly related to suicide intent than depression alone (see Wetzel et al. [8] for a review). Fawcett et al. (IS), for example, in a prospective study of a heterogeneous study of psychiatric patients, found that the hopelessness rating from the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (

16) was among the factors that differentiated the 25 patients who committed suicide from the 929 survivors. The relationship between hopelessness and suicide has also been demonstrated in schizophrenic patients, a group that is also at a significant risk for committing suicide (

17). Drake and Cotton (

18) found that ratings of hopelessness derived from the patients’ charts, completed during hospitalization, accounted for the relationship between depression and suicide in a group of schizophrenic inpatients who eventually committed suicide: The hopelessness ratings were the best predictor of eventual suicide in their sample. The foregoing findings may explain the perplexity reported by clinicians who are confronted with unexpected suicidal deaths among discharged schizophrenic patients (

19,

20), in the absence of assessment of hopelessness.

The present study and related research (

9) represent a departure from previous investigations (

21) of suicide prediction that have largely been limited to the study of demographic (e.g., socioeconomic status, unemployment status), organismic (e.g., gender, age), and past history (previous suicide attempts, alcoholism) variables. In contrast, hopelessness, as a measurable psychological dimension, represents an ongoing fluctuating index of relative suicide potential within these risk groups and provides a means for gauging the effects of clinical interventions. Further, in contrast to demographic variables, hopelessness is subject to direct clinical intervention.

One possible objection to the use of the Beck Hopelessness Scale in prediction is that in the present study it yielded a large proportion of false positives (59.0%). The nearly inevitable overinclusiveness of valid predictors of rare phenomena such as suicide was first demonstrated by Meehl and Rosen (

22) and has since been widely discussed (

23–

25). However, it should be noted that the connotations of the terms “false negative” and “false positive” may not be completely appropriate in the present context. Generally, these terms are applied when a specific test is able or unable to demonstrate the

presence or absence of a known disease, such as diabetes or tuberculosis. However, the Beck Hopelessness Scale attempts to identify the

potential for fatal suicide attempts and not the behavior itself. Many persons with high scores on this scale may continue to be at risk for suicide beyond the observation period, even though they have not yet made a fatal suicide attempt.

In the interpretation of the results of the present study, hopelessness may best be construed as a

risk factor—perhaps analogous to a history of smoking or elevated blood pressure as a predispositional factor in heart disease. In this connection, Murphy (

17) has commented, “In the clinical context . . . the problem of false positives is not what it is in the laboratory. The decisions made are investigation and treatment decisions, involving much more than the issue of suicide. There is the continuing opportunity for feedback, and thus for modification of risk assessment and intervention.”

In clinical practice, it would seem to be desirable to define and monitor patients at high risk for suicide. In addressing the issue of the economic cost of following a large number of high-risk patients who may or may not eventually commit suicide, Pallis et al. (

26) stated:

Since nearly two thirds of attempters are likely to receive inpatient or outpatient psychiatric care—a number far exceeding that classified high risk on any scale—the question is not whether to treat a high risk group but how to ensure that it includes most of the true prospective suicides [italics added] . . . by using [valid predictors of suicide], one is more likely to ensure that those at the highest risk would receive a closer follow-up or more appropriate attention. (p. 147)

Why does hopelessness serve as such a powerful predictor of eventual suicide? We believe that the intensity of hopelessness displayed during one depressive episode is indicative of the level that emerges in future episodes. In preliminary explorations of this issue, Beck (unpublished data, 1988) studied 59 outpatients at the center for cognitive therapy who sought treatment on two different occasions. Their mean±SD Beck hopelessness score at the index admission was 8.97±4.68, and their mean score at the time of the next admission to our clinic was 10.73±4.89. The correlation between index and reevaluation hopelessness scores was 0.51. Since the patients applied for readmission to the clinic because of recurrence of their index disorder or the appearance of a different disorder, the Beck hopelessness score at readmission was uniformly higher than at the time of the previous discharge from the clinic and may be regarded as indicative of a psychiatric disturbance or personal crisis rather than as a stable trait measure.

In this context, hopelessness as it occurs in depressed patients may be viewed as having state and trait characteristics. It rises and falls as the disorder develops and subsides. At the time of recurrence of the disorder it increases approximately to the same level as that reached at the time of the previous episode. Thus, a patient with severe depression but mild hopelessness or a patient with modest depression with marked hopelessness in one episode is prone to the same pattern in subsequent episodes. People who respond with marked hopelessness in one personal crisis will be likely to respond in the same way at the next crisis. Some individuals, however, are chronically hopeless regardless of whether they are depressed and are prone to suicidal wishes and behavior on a continuous basis. In such cases, hopelessness may constitute a stable belief, incorporating negative expectancies that are very resistant to change in suicide-prone patients.

In any event, hopelessness is an important clue that should alert clinicians to immediate or long-term suicide potential. It should be emphasized, however, that a comprehensive assessment of suicide risk should include, in addition to Beck hopelessness scores, such clinical predictors of suicide as the presence of an affective disorder, a high level of suicide ideation, a history of suicide attempts, a family history of suicide, a history of alcohol and drug abuse, and relevant demographic factors such as age, sex, and race. Future studies should be conducted to determine the applicability of the Beck Hopelessness Scale to a variety of other clinical populations, as well as to replicate the findings of the present investigation.

Finally, as mentioned earlier, hopelessness, unlike certain other predictors of suicide, such as age, sex, or race, is a characteristic that can be modified. A study by Rush et al. (

27), in fact, showed that depressed patients treated with cognitive therapy showed a more rapid reduction in hopelessness scores than a comparison group of depressed patients treated with an antidepressant drug. Effective nonpharmacological treatments have an additional advantage in that they do not carry with them the additional risk of intentional overdose with antidepressant medication, as was the case with four of the 17 patients who committed suicide in the present study.