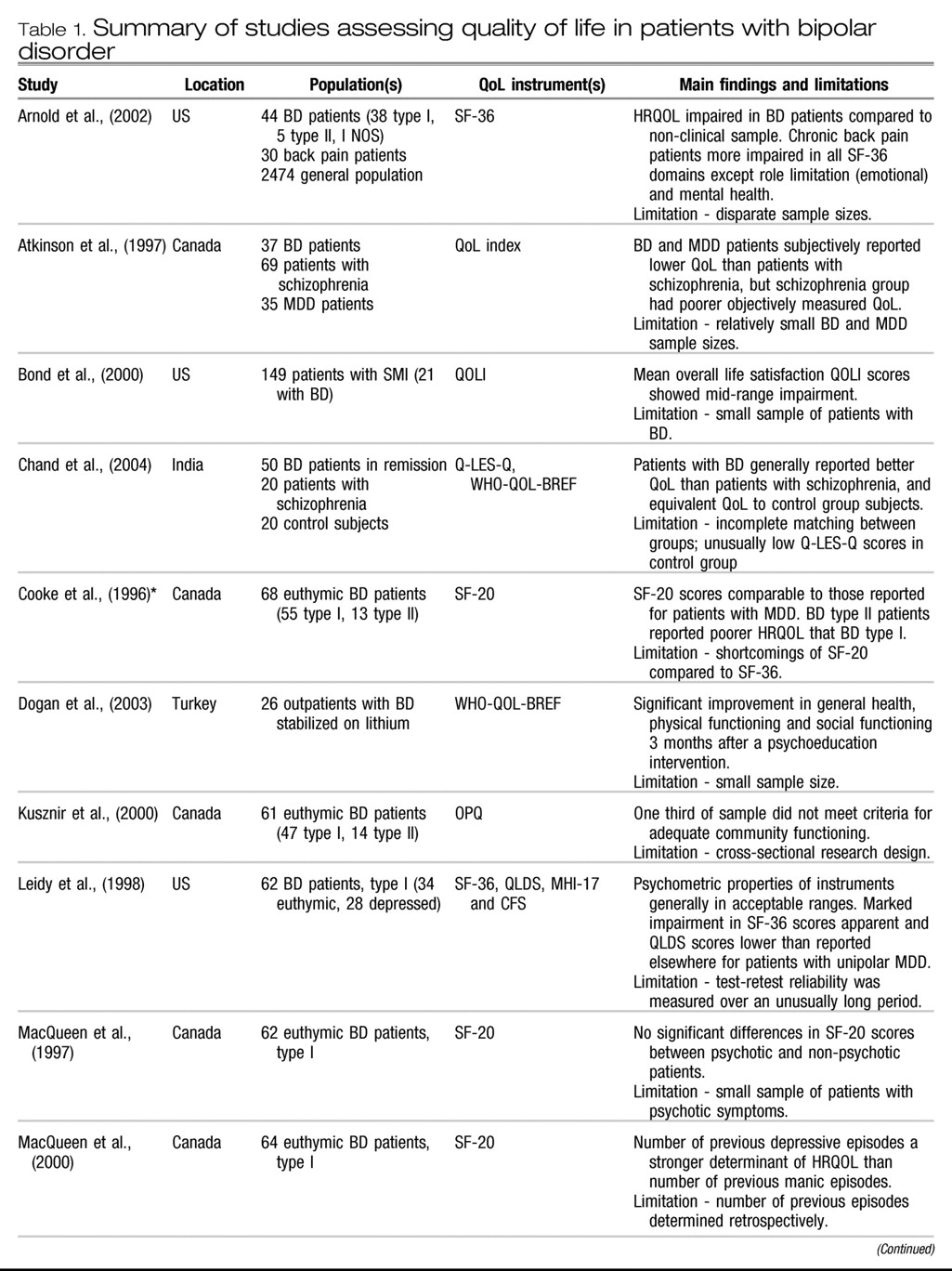

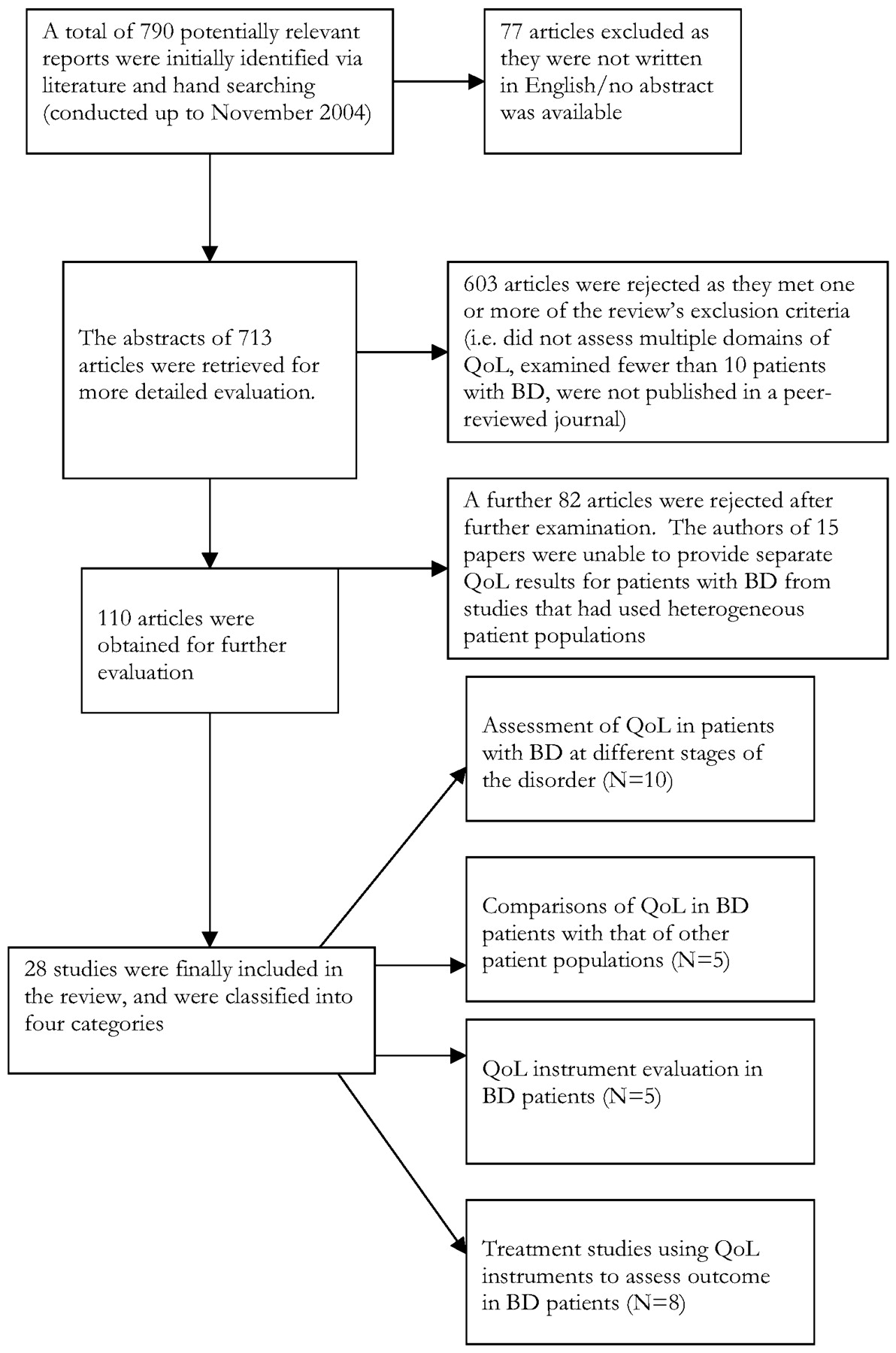

This section will review the 28 studies we identified. For ease of interpretation they are classified into the following four categories, although several studies met criteria for more than one category.

i) Assessment of QoL in patients with BD at different stages of the disorder

We identified ten studies of QoL in patients with BD at different stages of the disorder. Four of these were generated by a research group in Canada, and will be dealt with in unison. Following this, six other studies (one comparing QoL in patients with during different phases of the disorder, a recent study assessing QoL in bipolar depression, one performed in a Turkish sample of interepisode patients, one conducted in a sample of patients attending a mental health service in Italy, one in recently discharged patients in Nigeria and a report on patients enrolled in the STEP-BD Program) will be described.

A research group in Toronto, Canada has generated a series of interrelated reports on QoL in BD. Three of the series (

26–

28) describe various aspects of QoL in a single sample of outpatients (N = ~68) with BD type I (with manic episodes) or II (with hypomanic episodes) who had been clinically euthymic for at least one month (these have been counted as one study for the purposes of this review). Three of the series report on QoL in other patient populations (

29–

31). Cooke and colleagues (

26) examined levels of HRQOL using the MOS SF-20, (

32) a self-report questionnaire designed to assess perceived well-being in six domains (physical, social and role functioning, mental health status, health perceptions and bodily pain). Mean scores on the SF-20 domains in study patients were comparable to those reported for patients with MDD by Wells and colleagues in the large RAND Corporation MOS Study (

33). Analysis of SF-20 scores by type of BD showed that patients with BD type II reported significantly poorer HRQOL than BD type I in the areas of social functioning and mental health. In another paper, Robb and colleagues (

27) reported on functioning in the context of the ‘Illness Intrusiveness Model’ in patients with BD (

34,

35). The model addresses the impact a disorder and/or its treatment has upon an individual’s activities across 13 life domains: health, diet, active/passive recreation, work/financial status, self expression/improvement, family relations, relations with spouse, sex life, other relationships, religious expression and community involvement. The Illness Intrusiveness Rating Scale (IIRS) is used to yield a ‘total illness intrusiveness’ (TII) score. Illness intrusiveness occurred in several areas of functioning, with TII being associated with higher Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (Ham-D) scores, patients having experienced a recent episode of depression and having type II BD. Robb and colleagues (

28) specifically focused upon gender differences in SF-20 scores, finding that women possessed numerically lower scores in all of the questionnaire’s domains except for mental health, with significant differences in the domains of pain and physical health. Interestingly, objective measures of functioning (clinician rated Global Assessment of Functioning or GAF scores) were not significantly different by gender.

MacQueen and colleagues (

29) examined SF-20 scores in euthymic BD type I patients (N = 62) with or without psychotic symptoms during an index episode of mania. No significant differences in SF-20 scores were apparent between patients with or without psychosis, although the sample identified with psychosis may have been too small (N = 16) to detect statistically significant differences between sub-groups. Kusznir and colleagues (

30) assessed levels of community functioning via the Occupational Performance Questionnaire (OPQ) in a similar population, finding that one-third of patients did not meet criteria for adequate functioning on the ‘Community Functioning Scale’ component of the questionnaire. Finally, MacQueen and colleagues (

31) focused upon the effect of number of manic and depressive episodes on SF-20 and GAF scores in euthymic patients (N = 64), finding that number of past episodes of depression was a stronger determinant of HRQOL than number of previous manic episodes. Good correlation between the subjectively rated SF-20 and objectively rated GAF scores provided some evidence that euthymic patients with BD are capable of providing accurate descriptions of their HRQOL.

A potential advantage of this series of studies is that the majority of them were conducted in euthymic outpatients; interepisode patients are likely to be less prone to the effects of cognitive distortion than are symptomatic patients. However, euthymic patients are not necessarily asymptomatic as many have mild sub-syndromal symptoms, and several studies in this review will demonstrate that even residual depressive symptoms can be strongly associated with impaired QoL. The relationship between QoL and hypo/mania is less well understood. Both mania and hypomania can be associated with substantial depressive symptomatology, either in the form of ‘dysphoric mania/hypomania’ or when the patient experiences a mixed episode. This understanding led Vojta and colleagues to hypothesize that patients with manic symptoms would report significantly lower QoL than would patients who were euthymic (

36). To test this theory, the authors administered two brief self-report measures (the SF-12 and the EuroQoL visual analog scale) in bipolar patients with mania/hypomania (N = 16), MDD (N = 26), mixed mania/hypomania and depression (N = 14) or who were euthymic (N = 30). In keeping with their hypothesis, patients with mania/hypomania did show significantly lower SF-12 mental health scores than euthymic patients, with depressed or mixed patients showing significantly poorer HRQOL again. Mean EuroQoL scores ran in the same direction, although the difference between euthymic and manic/hypomanic patients was not significant.

In the largest study to date of QoL in bipolar depression, Yatham and colleagues have reported on SF-36 scores in BD type I patients (N = 920) who were either currently depressed, or had experienced a recent episode of depression (

37). SF-36 scores were remarkably low in the role-physical, vitality, social functioning, role-emotional and mental health sub-scales (see Table 2). The authors went on to compare these scores with those derived from seven large (> 100 outpatients) studies of HRQOL in unipolar depression that had also administered the SF-36. Sub-scale scores tended to be lower in the bipolar sample than in the unipolar sample, with the exception of the bodily pain sub-scale, where unipolar depressives tended to exhibit higher scores. Mean SF-36 scores were significantly (weakly: range −0.1 to −0.3) negatively correlated with HAM-D scores, providing some evidence for the construct validity of the instrument in this population. Whilst this study is robust in terms of its large sample size and well-described clinical population, it did not control for depression severity or demographic variables in between-group comparisons. Furthermore, diagnosis of bipolar disorder was made by careful clinical interview, whereas unipolar depression was diagnosed via a number of subjective and objective methods.

A study by Ozer and colleagues (

38) assessed 100 interepisode patients with BD in Turkey with the aim of examining the impact of ‘history of illness’ and ‘present symptomatology’ factors upon a variety of outcome measures including the Schedule for Affective Disorder and Schizophrenia (SADS) and Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (Q-LES-Q) (

39). The Q-LES-Q is a 93-item self-report measure of the degree of enjoyment and satisfaction in various areas of daily living. The questionnaire was developed and validated for use in depressed outpatients and has eight summary scales that reflect major areas of functioning: physical health, mood, leisure time activities, social relationships, general activities, work, household duties and school/coursework. Mean Q-LES-Q scores can be derived from the eight summary scales and range from 0–100, where higher scores indicate better QoL. Using multivariate analysis, Ozer and colleagues found that none of the historical variables (including age at first episode, number of previous depressive/manic episodes, duration of illness, number of hospitalizations, age at first hospitalization, or number of symptoms during first episode) were predictive of mean Q-LES-Q scores. Of the current symptoms assessed, only the depression subscale of the SADS interview significantly predicted lower Q-LES-Q scores, accounting for only 13% of the observed variance. When the patient population was subdivided into three groups (low, moderate and high) according to severity of SADS depression scores, mean Q-LES-Q scores were 39%, 38% and 35%, respectively. In comparison, mean Q-LES-Q scores have been reported to be 42% in hospitalized psychiatric inpatients (

40), 42% in outpatients with MDD (

41), 44% in patients with seasonal affective disorder (SAD) (

41), 53% in patients with chronic MDD (

42), and 83% in the general population (Rapaport, personal communication).

Ruggeri and colleagues (

43) investigated the relationship between QoL and a variety of clinical and demographic variables in a community-based sample of patients (N = 268) with mixed psychiatric diagnoses, 22 of whom were bipolar. QoL was assessed via the Lancashire Quality of Life Profile (LQOLP), which assesses perceived well-being and functioning in 9 major life domains on a 7-point Likert scale (where higher scores indicate better QoL). We extracted LQOLP results for the bipolar sample from data provided by the authors, finding that mean satisfaction scores for the 9 domains were 4.4 ± 1.0, a score similar to that reported for the entire patient sample. In another study of recently discharged Nigerian outpatients (N=25) with BD type I or II, World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHO-QOL-BREF-TR) scores were reported to be ‘good’ in 5 (20%) of patients, ‘fair/average’ in 14 (56%) and ‘poor’ in 6 (24%) of patients (data by WHOQOL-Bref domain also provided by authors during personal communication) (

44).

Finally, Perlis and colleagues have recently provided an analysis of ‘early onset’ in 983 patients (BD type I, II or NOS) enrolled in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) (

45) in which QoL was assessed. The multicentre STEP-BD program, a large prospective, naturalistic study than combines several randomized-controlled trials, has selected to use the Q-LES-Q to assess QoL and the GAF and ‘Range of Impaired Functioning Tool’ (LIFE-RIFT) to measure functional status. Perlis and colleagues provide the first report on QoL from the project, having looked specifically at the effect of age of onset (grouped into ‘very early age, <13 years’, ‘early age, 13–18 years’ and ‘adult, >18 years’) of mood symptoms in BD upon outcome. Younger age of onset was found to be a significant predictor of Q-LES-Q scores at study entry (where treatment and clinical status would have varied widely between patients), but not of functioning as measured by the GAF or LIFE-RIFT. These results represent early data from a study that has the potential to address several important questions surrounding QoL in BD.

ii) Comparisons of QoL in patients with BD with that of other patient populations

We identified five studies comparing QoL between patients with BD and patients with other conditions. Two of these used the SF-36, one used the ‘Quality of Life Index’, the Q-LES-Q and the WHO-QOL-BREF and one applied a ‘health utilities’ model.

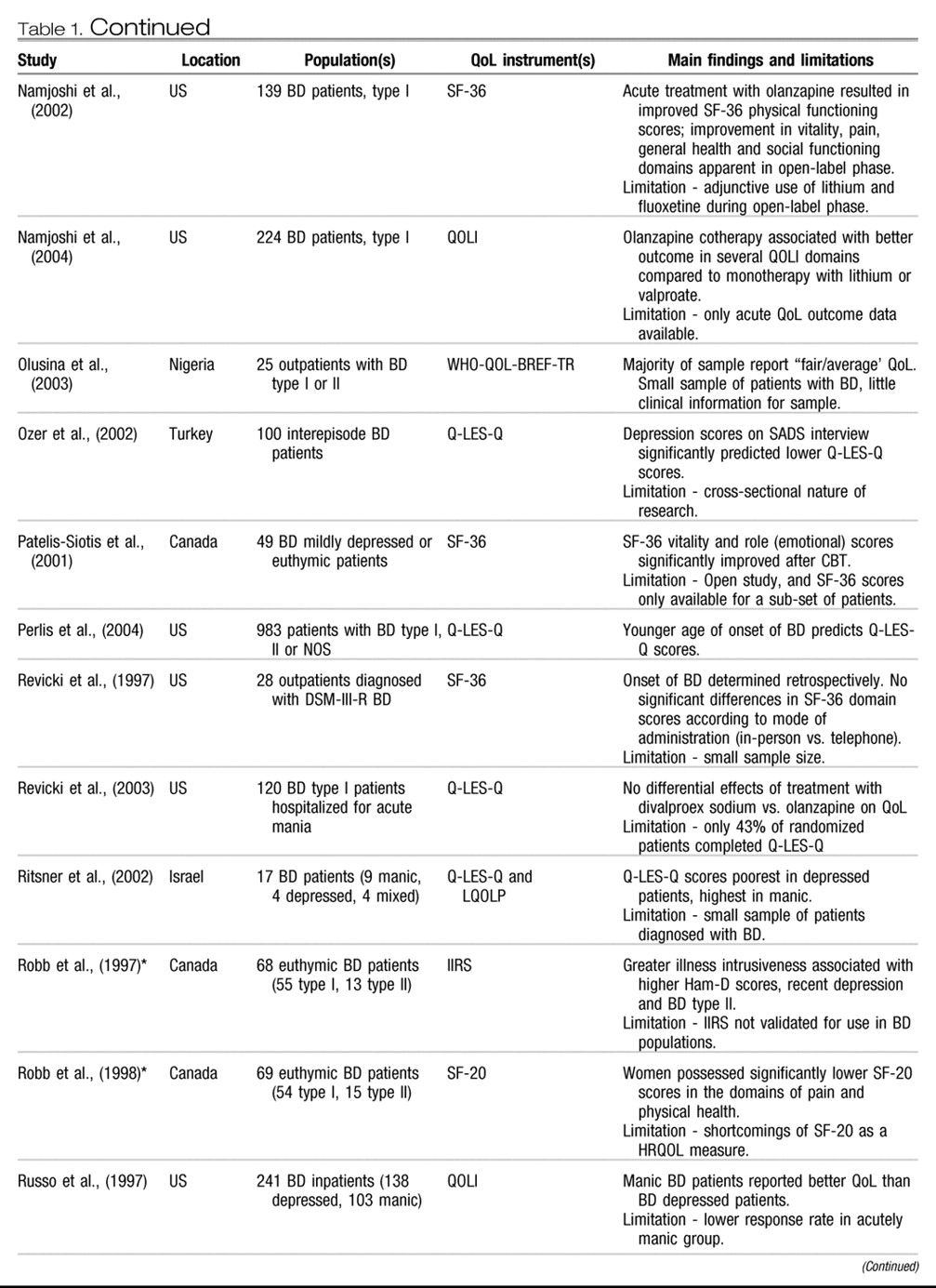

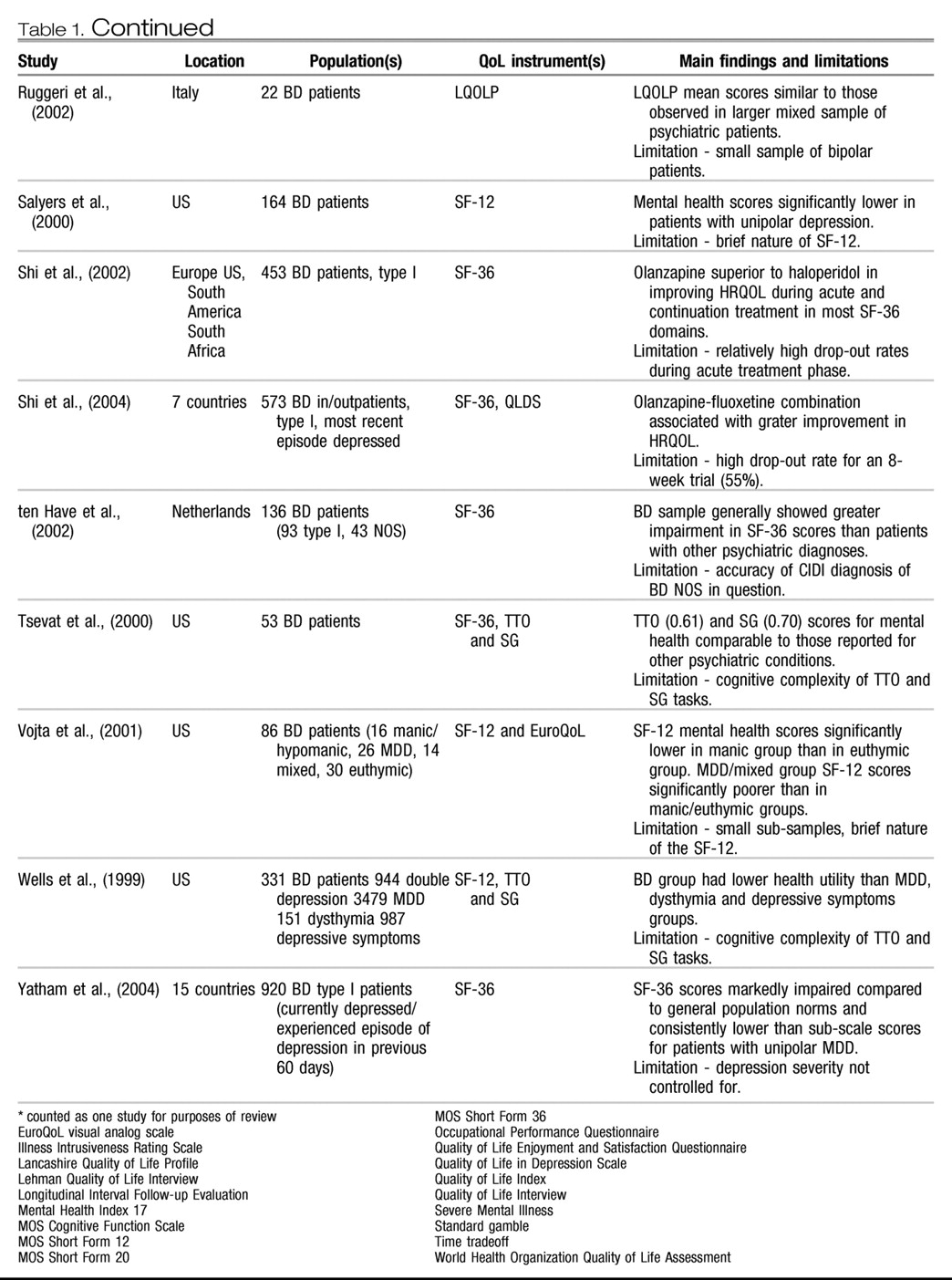

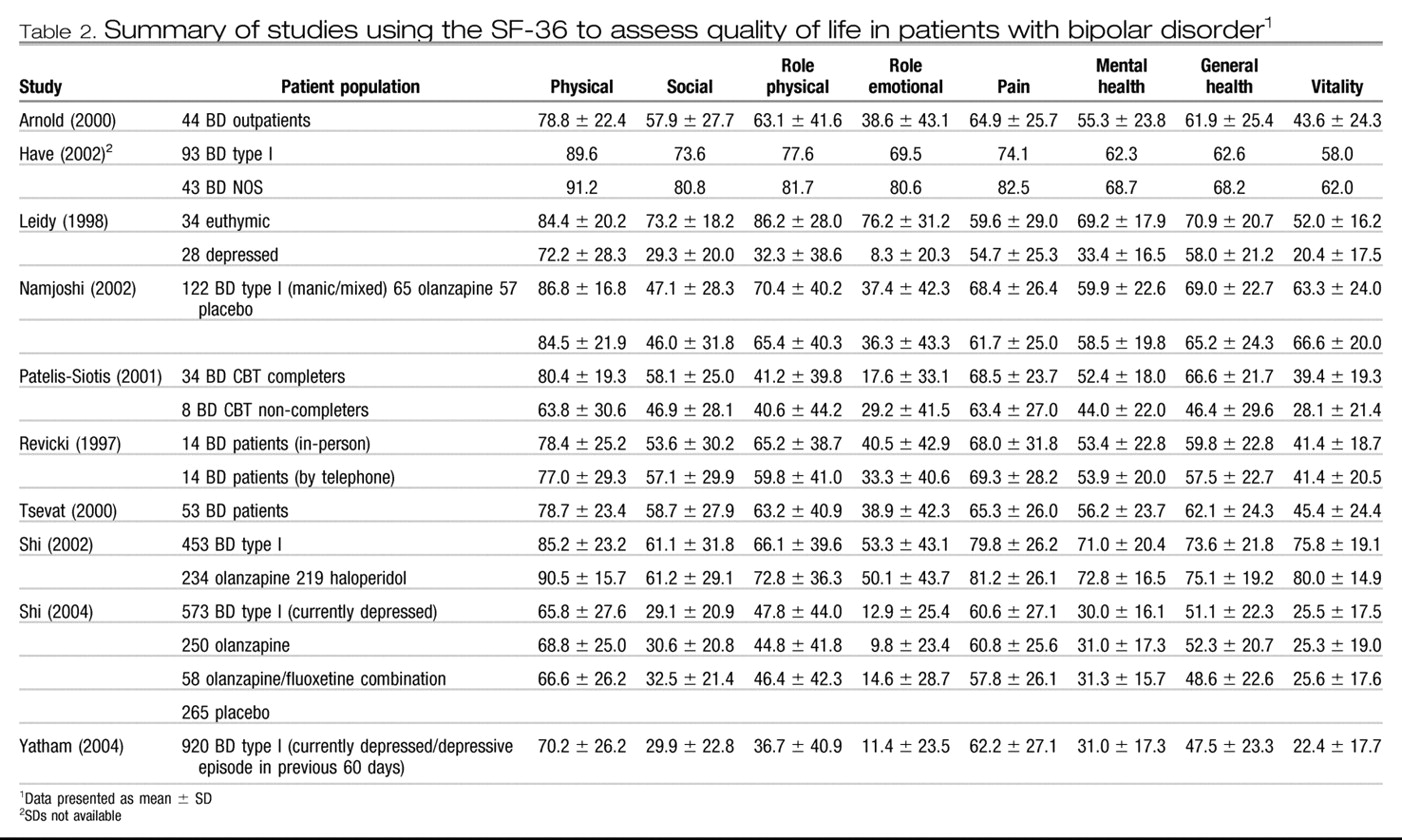

The SF-36 (

46) is currently the most widely used measure of HRQOL (

47). The self-report questionnaire contains eight sub-scales assessing physical functioning, social functioning, role limitations (physical), role limitations (emotional), pain, mental health, general health and vitality. These yield an overall domain score on a 0–100 scale, where 0 represents worst possible health and 100 best possible health. Arnold and colleagues (

48) compared SF-36 scores between patients with BD (N=44) and chronic back pain (N=30) with norms previously reported for a general population sample (N=2,474) (

49). The results of the study indicated that HRQOL was compromised in all SF-36 domains except physical functioning in patients with BD compared with the general population sample (see Table 2). The BD group fared better than the back pain group in the physical, role limitation (physical), pain and social domains, although no significant differences were observed in terms of role limitation (emotional) or mental health domains. While the study provides a useful initial comparison of HRQOL between BD and other conditions, its findings should be interpreted with some caution owing to the disparate sample sizes involved. It also utilized previously published norms for the SF-36 that had been derived by different data collection methods.

The Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study (NEMESIS) has examined the epidemiology of psychiatric disorders in a large general population sample (

50). Using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), 136 adults were identified with DSM-III-R lifetime BD (93 with BD type I and 43 with BD NOS) and administered the SF-36. Participants with BD showed significantly more impairment in most of the questionnaire’s domains compared with NEMESIS subjects diagnosed with other psychiatric disorders (SF-36 scores for the BD group are presented in Table 2). For example, in the domain of mental health, participants with BD type I experienced significantly lower mean scores (62.3) than people with other mood (75.2), anxiety (74.0), substance use (80.2) or no psychiatric disorders (85.8). BD type I subjects also experienced significantly lower SF-36 scores than patients with BD NOS in the domains of mental health, role limitations (emotional), social functioning and pain. However, there remains some controversy about the accuracy with which the CIDI detects BD NOS, limiting somewhat the inferences that can be made on the basis of these sub-group results. A later analysis of a subset (N=40) of the original NEMESIS sample administered the EuroQol: 5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) scale, which can be used to provide health utility values (

51). Mean utility values (see below) for the sample were reported to be 0.82±0.20, comparable to those observed in the general population of the Netherlands.

Atkinson and colleagues (

52) used a different measure, the ‘Quality of Life Index’ (

53), to assess QoL in patients with BD (N=37), MDD (N=35) or schizophrenia (N=69). The authors found that subjectively reported QoL was lower in patients with BD and MDD than in those with schizophrenia. Interestingly, this trend was reversed for objectively assessed QoL, which included measures such as medical history, health risk behaviors, educational and financial levels and social functioning. These findings led the authors to speculate about the validity of subjective measures of QoL, particularly in people with affective disorders. These results were not replicated in Indian by Chand and colleagues, who compared the QoL of patients with BD (in remission and stabilized on lithium prophylaxis, N=50) with patients with schizophrenia (N=20) and healthy controls (N=20) (

54). Using the Q-LES-Q and the WHOQOL-BREF, the authors found that the bipolar group reported significantly better QoL than the schizophrenia group in all domains of the Q-LES-Q, and in general well-being, physical health and psychological health on the WHO scale. Surprisingly, the authors also observed that perceived QoL was equivalent between patients with BD and healthy controls, with the exception of the Q-LES-Q leisure domain, where the patient group actually reported better functioning. Having said this, mean Q-LES-Q scores for this particular control group were unusually low (approximately 47%, where general population norms for the United States are around 83%, Rapaport, personal communication).

Although a growing number of studies have now evaluated the ‘health utilities’ and ‘health preferences’ of patients with physical conditions, relatively few have examined these values in patients with mental illnesses, including BD. The concept of health utility refers to an individual’s preferences for different health states under conditions of uncertainty. Health preferences are values that reflect an individual’s level of subjective satisfaction, distress or desirability associated with various health conditions. Health utility and preferences are frequently assessed by the ‘time tradeoff’ (TTO) and ‘standard gamble’ (SG) approaches (

55). TTO refers to the years of life a person is willing to exchange for perfect health. For example, patients might be asked to imagine that a treatment exists that would allow them to live in perfect physical and mental health, but reduces their life expectancy. They might then be asked to indicate how much time they would give up for a treatment that would permit them to live in perfect health, if they had ten years to live. SG refers to the required chance for successful outcome to accept a treatment that could result in either immediate death or perfect health. For example, patients might be asked to imagine that they had ten years to live in their current state of health, and that a treatment existed that could either give them perfect health, or kill them immediately.

Patients might then be asked to indicate what chance of success the treatment would have to have before they would accept it. Health utility and preference values are frequently expressed as a score of 0 to 1, with higher values representing better health.

We identified one study comparing health utility in patients with BD with other patient populations. Wells and colleagues (1999) (

56) assessed functioning and utility in patients with depression or chronic medical conditions within seven managed care organizations in the United States. HRQOL was assessed via the global mental and physical scales of the SF-12 and utility was measured via TTO and SG. Patients with depression were categorized as those with BD (N=331), 12-month MDD (N=3479), 12-month double depression (N=944), 12-month dysthymia (N=151) or brief subthreshold depressive symptoms (N=987). In terms of HRQOL, the bipolar group showed levels of impairment second only to patients with double depression. Utility was also lower in the bipolar group compared with patients with MDD, dysthymia or brief depressive symptoms, although not double depression. In terms of health utility, bipolar patients were willing to give up on average 17% of their life expectancy in return for perfect health, and would accept on average an 11% risk of death in exchange for perfect health. In comparison, patients with MDD were willing to give up 11% of their life expectancy, and accept a 6% risk of death.

iii) QoL instrument evaluation in patients with BD

We identified five studies that had evaluated different QoL instruments in BD populations and one study that examined the effects of mode of questionnaire administration. The first of these examined the application of the aforementioned health utility approach. The second assessed the psychometric properties of the Lehman Qualify of Life Interview (QOLI) in a heterogeneous sample of psychiatric inpatients. The third evaluated four QoL scales in a smaller sample of Patients with BD, while the fourth assessed the MOS SF-12 in a large population of patients with severe mental illness. The fifth study evaluated the properties of the Q-LES-Q and the LQOLP in a sample of Israeli patients with severe mental disorders. The final study we identified examined telephone versus in-person health status assessment in outpatients with BD.

Tsevat and colleagues (2000) (

57) examined functional status and health utility in 53 outpatients with BD recruited from one site of the multicenter Stanley Foundation Bipolar Network study. The authors aimed to assess how patients with BD rated their current overall health versus their current mental health, and to determine the extent to which health utility correlated with disease state. TTO scores for current overall health were 0.71, but were significantly higher than scores for current mental health, which averaged 0.61. In other words, patients with BD were willing to give up on average 39% of their life expectancy in return for perfect mental health. These values are similar to TTO values obtained in the Beaver Dam Health Outcomes Study in patients with depression (0.70) or anxiety (0.77). SG scores were not significantly different for overall health (0.77) and mental health (0.70). SF-36 scores for the study are presented in Table 2. Certain SF-36 domains (general health, vitality and role-emotional) were significantly correlated with mental health TTO and SG scores, but levels of mania were not correlated with utilities for either overall health or mental health. The authors concluded that health utilities may be related to certain health status attributes and to level of depression, but may not be related to level of mania in patients with BD. One advantage of the health utility/preference approach to QoL assessment is that it allows the calculation of quality-adjusted life years (QALYs). QALYs are a commonly used outcome measure in cost-effectiveness studies, but our literature search did not find any studies that had calculated QALYs for BD populations.

Russo and colleagues (

58) performed a rigorous psychometric evaluation of the QOLI (

59) in a large sample (N=981) of acutely ill hospitalized psychiatric inpatients. Of these, 138 were diagnosed according to DSM-III-R criteria with bipolar depression, 103 with acute mania and the remainder with unipolar depression, schizophrenia, or ‘other’ diagnoses. The QOLI contains 44 items and 7 satisfaction scales, a global satisfaction item and 14 functional items, with all satisfaction scores ranging from 1 (terrible) to 7 (delighted). Patients were administered the instrument using a structured interview procedure within 48 hours of admission and discharge. While the QOLI was successfully completed by 90% of patients overall, rates did vary according to patient diagnoses with non-completion rates being lowest in patients with bipolar depression (12%) and highest in manic patients (31%). Reasons given for non-completion of the measure varied, the most common being ‘inadequate staff time’ (39%), ‘patient too psychotic, demented, or confused’ (13%), or ‘too agitated or sleepy’ (12%). The QOLI showed good psychometric properties overall, although there was some concern about an apparent lack of construct consistency (low correlations between satisfaction and functional measures) in patients with mania. Analysis of QOLI sub-scales showed that, broadly speaking, manic patients reported the highest levels of satisfaction and function, with bipolar and unipolar depressed patients reporting the lowest levels.

Leidy and colleagues (

60) examined the psychometric properties of four QoL measures in 62 BD type I patients (34 euthymic, 28 depressed). Patients completed the SF-36, the Quality of Life in Depression Scale (QLDS), the Mental Health Index 17 (MHI-17) and the MOS Cognitive Function Scale (CFS). The study provided further evidence that both euthymic and depressed patients with BD are capable of providing subjective reports of their HRQOL. Baseline SF-36 scores were markedly impaired in the depressed sub-group, with the vitality, social and role limitation (emotional) domains all falling below the 25

th percentile (see Table 2). QoL as measured by the QLDS was poorer than has been reported elsewhere for patients with unipolar depression. Cronbach’s alpha scores for the QLDS, MHI-17, CFS and four of the eight SF-36 sub-scales (physical functioning, role physical, vitality and metal health) all fell above the generally accepted level of 0.80. Test-retest reliability for the scales were modest (intraclass correlations ranged between 0.18 on the SF-36 role emotional scale and 0.80 for physical functioning), although the reliability of the scales was assessed over an unusually long time period (8 weeks). Scores on the QLDS, MHI-17 and CFS were significantly correlated with patients’ Ham-D scores, as were several of the SF-36 sub-scales, thus confirming the construct validity of the scales in patients with BD. Finally, the MHI-17, CFS, QLDS and SF-36 vitality, role emotional and mental health sub-scales were shown to be responsive to change in depression status over time; the QLDS has recently been successfully used as an outcome measure in a large pharmaceutical treatment trial (Shi et al., 2004, see section IV).

Salyers and colleagues (

61) conducted a psychometric evaluation of another MOS instrument, the SF-12 (

62), in a sample of 946 patients with severe mental illness, 164 of whom were diagnosed with BD. Mean (±SD) SF-12 physical functioning and mental functioning scores for the bipolar group were 46.1±11.5 and 39.6±12.7 respectively, although mental health functioning scores were significantly lower (31.8±13.4) in patients with unipolar MDD. The instrument showed acceptable levels of reliability and validity in the entire sample, although it is worth noting that is was administered by trained interviewers, rather than as a self-report measure.

Ritsner and colleagues (

63,

64) have compared responses on the Q-LES-Q and the LQOLP in a sample of 175 non-clinical controls and 199 Israeli patients with severe mental illness (SMI), 17 of whom were diagnosed with BD. In personal communication with the authors, we were informed that mean Q-LES-Q scores for the manic, depressed and mixed sub-groups of Patients with BD in the study were 40%, 25% and 33% respectively. Both instruments showed generally acceptable levels of internal consistency, test-retest reliability and criterion validity (in the entire patient population) but notably low levels of convergent validity between the instruments’ domains, particularly in the control group. Finally, Revicki and colleagues (1997) (

65) examined the effects of administering the SF-36 either in person or by telephone in 28 patients with BD (see Table 2). SF-36 domain scores were not significantly affected by mode of administration.

iv) Studies using QoL instruments to assess outcome in patients with BD

We identified eight studies that had used a QoL measure to assess outcome in BD populations: five clinical trials that examined pharmacological interventions for the disorder and three studies that assessed non-pharmacological interventions.

Namjoshi and colleagues from a Lilly research group have conducted a series of studies examining the impact of treatment with olanzapine upon QoL (

66–

70). In the first, Namjoshi et al., (2002) evaluated the impact of acute (3-week) treatment with olanzapine or placebo and long-term (49-week open label) treatment of BD type I (manic/mixed). Baseline SF-36 scores for the olanzapine and placebo group are shown in Table 2. During acute-phase treatment, a significant improvement was observed in the physical functioning domain of the SF-36 in the olanzapine group. During the open label treatment period, however, the SF-36 bodily pain, vitality, general health and social functioning domains showed significant improvements over time. This may indicate that olanzapine has a relatively rapid effect in terms of improving physical functioning in patients with acute mania, but that treatment may be required for longer periods for functioning to improve in other QoL domains.

Shi and colleagues have also compared the treatment effects of olanzapine and haloperidol in patients with acute mania (N=453) (

67,

68) weeks of acute-phase treatment, significantly greater improvement in five of the SF-36 domains (general health, physical functioning, role limitations -physical, social functioning and vitality) was apparent in the olanzapine group. Superiority of olanzapine over haloperidol persisted over the study’s 6-week continuation phase, with concomitant improvements in work and household functioning. Baseline SF-36 scores for the olanzapine and haloperidol groups are shown in Table 2. A further study examined the effects of adding olanzapine to lithium or valproate in patients with BD (N=224) (

69). Olanzapine cotherapy was associated with better outcome in several QOLI domains compared to monotherapy with lithium or valproate alone. The SF-36 and QLDS have been used in a study comparing the benefits of olanzapine alone versus an olanzapine-fluoxetine combination or placebo (

70). Compared with placebo, patients who received olanzapine showed greater improvement at 8 weeks in SF-36 mental health summary scores, and in mental health, role-emotional and social functioning domain scores (SF-36 scores summarized in Table 2). The combination group fared significantly better in terms of HRQOL improvement than the olanzapinealone group, showing improvement in 5 of the SF-36 domain scores and in QLDS total score. The authors also performed a psychometric evaluation of the QLDS (see section III).

Finally, the Q-LES-Q has been administered at baseline (hospital discharge), 6 and 12 weeks in a comparison of divalproex sodium and olanzapine in the treatment of acute mania (

71). No significant treatment effects were detected in Q-LES-Q scores in the study, although only 52 (43%) of the 120 patients randomized to either divalproex or olanzapine completed the QoL instrument. Interestingly, the authors reported an association between weight gain being reported as an adverse event and poorer change scores in the physical, leisure, and general activities domains of the Q-LES-Q at 6 weeks (but not at 12 weeks). Negative correlations were reported between increased weight (at 6 weeks) and overall life satisfaction, physical health, mood, general activities and satisfaction with medication on the Q-LES-Q.

Although current recommendations favor the use of pharmacological treatments such as lithium and mood stabilizers in the initial treatment and symptom control of BD, there is increasing recognition of the role of psychotherapy in the management of the disorder. We identified one study that had used a QoL tool to assess outcome following a psychotherapy intervention for BD. Patelis-Siotis and colleagues (

72) used the SF-36 in a feasibility study of group cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) in patients with BD. Although baseline SF-36 data was available for 42 patients (see Table 2), pre and post intervention data was only available for a proportion of participants (N=22) as completion of the QoL questionnaires was optional. Nevertheless, SF-36 vitality and role emotional scores were significantly improved following CBT, with an accompanying trend towards improved social functioning. Another study we identified specifically examined the effects of vocational rehabilitation upon outcome in 149 patients with SMI, 21 of whom were diagnosed with bipolar disorder (

73). In personal communication with the authors, we learned that mean (± SD, range 1–7 where higher scores indicate better QoL) baseline QOLI ‘overall life satisfaction’ scores were 4.7±1.1, with ‘general satisfaction’ domain scores of 4.9±1.3. Although outcome data was not available specifically for the bipolar group, better QoL outcomes were associated with ‘competitive work activity’ in the overall sample compared to other reduced forms of work activity. Finally, a recent study has examined the effects of providing 3 sessions of psychoeducation about lithium treatment to patients (N=26) with BD (

74). In addition to assessing the effects of psychoeducation upon medication adherence, the authors examined the impact of education upon QoL, as measured by the WHO-QOL-BREF. Following psychoeducation, patients in the intervention arm of the study showed significant improvement in 2 of the WHOQOL BREF’s 4 domains (physical health and social functioning) and in overall perceived health. Patients in the control arm of the study, in comparison, showed no significant changes in their perceived QoL. The results of the study indicate that it may be possible to alter patients’ perceptions of their QoL even with relatively brief psychological interventions.