Over the past 15 years, in response to public and professional recognition of problems in the care of patients at the end of life, palliative care has emerged as a clinical discipline focused on the provision of comprehensive, interdisciplinary care focused on maintaining and enhancing quality of life for patients living with advanced, progressive, life-threatening illness and for their families. In 1994, the Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatment (SUPPORT) of more than 9000 patients in five academic medicine centers across the country, demonstrated pervasive problems in care of patients at the end of life, including deficits in pain management, knowledge of and adherence to patient preferences for life-prolonging care, frequent use of aggressive care without benefit, and depletion of family resources (

1,

2). Additional research has demonstrated high levels of family dissatisfaction with symptom management, communication, emotional support, and respect provided to the patient; the highest levels of satisfaction were reported for patients cared for by hospice (

3,

4). Undertreatment of symptoms, especially in nursing homes, remains a significant issue (

5). Discussions about physician-assisted suicide (PAS) built on patients' fears that they would suffer and that their wishes would not be honored at the end of life and resulted in the legalization of PAS, under specified circumstances, in the state of Oregon in 1997. In addition, this often-contentious dialogue contributed to the strengthening of the ethical foundation for withholding and withdrawing life-sustaining treatment, aggressive use of medications for pain and other physical suffering, even if such treatment might hasten death (the so-called “double effect”) (

6), and greater appreciation of the role of psychiatric disorders (e.g., depression and anxiety), as well as patients' psychological characteristics (e.g., desire for control), as factors in patients' desires to hasten death (

7). A growing evidence base in palliative care has identified patient perspectives on high-quality end-of-life care, focusing on the elements of optimizing physical comfort, maintaining a sense of continuity of one's self, maintaining and enhancing relationships, making meaning, achieving a sense of control, and confronting and preparing for death (

8,

9).

The field of palliative care has grown rapidly in the United States, mirroring earlier growth in the United Kingdom. Hospice use has grown from 158,000 patients per year in 1985 to 1.2 million patients per year in 2005 (

10) (approximately one third of all deaths) and has become a $9 billion care system; more than 2200 physicians have been certified in Hospice and Palliative Medicine, and more than 1300 hospitals have developed clinical palliative care services. In 2007, Hospice and Palliative Medicine became an Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)- and American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS)-recognized subspecialty of Internal Medicine, with 10 cosponsoring boards, including the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology. Over a similar time frame, the ACGME and the Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) have promulgated standards for education in end-of-life care for medical students and residents (

11,

12). Although medical students and residents continue to have major deficits in their preparation to care for patients with palliative care needs, research demonstrates positive attitudes and interest in learning these clinical competencies. Psychosocial care and communication emerge repeatedly as areas of particular weakness in physicians' educational preparation for caring for patients at the end of life (

13). Research in palliative care has lagged behind clinical and educational development; however, the evidence base for the field is rapidly improving.

TREATMENT STRATEGIES AND EVIDENCE

A growing body of evidence suggests that the provision of palliative care services is associated with improved symptom control, improved quality of life, better communication, greater concordance between patient wishes and care received, reduced caregiver distress, improved family satisfaction, a greater likelihood of death at home, enhanced bereavement outcomes for survivors, and reduced hospital costs.(

3,

14–

20). We are learning that spirituality and religion represent valuable resources that help patients cope and that spiritual support is associated with better quality of life in patients with advanced cancer (

21). Although only about one fifth of patients with advanced cancer are both aware of their terminal prognosis and at peace about it, this state of “peaceful awareness” is associated with better mental health and quality of death; physician communication about prognosis appears to be associated with peacefulness at the end of life (

22). Proactive communication strategies, including providing a brochure, as well as greater opportunities for families to express their feelings and concerns, appear to enhance family support, appropriate end-of-life decision making, and bereavement outcomes among patients hospitalized in an intensive care unit and their families (

23). Cultural differences in values about end-of-life care are now appreciated, enabling clinicians to better understand the wishes of an increasingly diverse population. For example, African Americans are more likely to prefer and receive less information disclosure and more aggressive care at the end of life, whereas Hispanics prefer aggressive care, but receive it less often (

24). New strategies for treatment of depression in advanced illness (

25,

26), psychotherapies to enhance quality of life at the end of life (

27,

28), and complicated bereavement are also emerging (

29).

THE PALLIATIVE CARE CLINICAL APPROACH

Palliative care clinicians seek to understand and treat the physical, psychological, spiritual, and social components of the patient's and family's distress, within a model that views the patient and family as a single unit. The focus of care is on alleviation of suffering and restoring the patient to a sense of “wholeness” (

30). Care is provided across the entire age spectrum (

31). Outstanding communication competencies are integral to the practice of palliative medicine (

32). Whereas the traditional focus of medicine is cure and life prolongation, palliative care complements these goals with the focus on optimizing quality of life for the patient and family. Palliative care clinicians provide expert symptom assessment and meticulous treatment of pain, often using medications, nonpharmacologic treatments (e.g., meditation or hypnosis), and interventional approaches; similar intensive strategies are used to treat other common symptoms at the end of life, including nausea, fatigue, insomnia, and constipation. Palliative care clinicians also seek to evaluate and treat psychiatric disorders (e.g., depression, anxiety, and delirium) as well as to help patients explore feelings of grief, loneliness, fear and uncertainty about the future, and concerns about loved ones. Spiritual/religious and existential issues are also a focus of assessment and treatment. Anger at or isolation from God, guilt about past behavior, and uncertainty and fear about the afterlife are among the common issues that arise in this domain; in addition, existential concerns about the meaning, purpose, and value of one's life arise frequently and are the subject of attention. The impact of the patient' s illness on family members, the toll of caregiving, preparation for death, bereavement, and exploring concerns about key relationships are commonly a focus of palliative care. Because of the breadth and intensity of issues, as well as the shortened time frame for addressing them, an interdisciplinary team involving physicians, nurses, social workers, a chaplain, pharmacist, and, ideally, a psychiatrist works together to provide personalized treatment. Care can be provided in the inpatient, outpatient, nursing home, and home settings; inpatient palliative care programs may provide consultative services or have specialized units for care of patients with palliative care needs. Hospice is an invaluable resource for the provision of care in the community; more than 90% of hospice services are provided in patients' homes, whereas a small proportion are provided in nursing homes and inpatient hospice facilities.

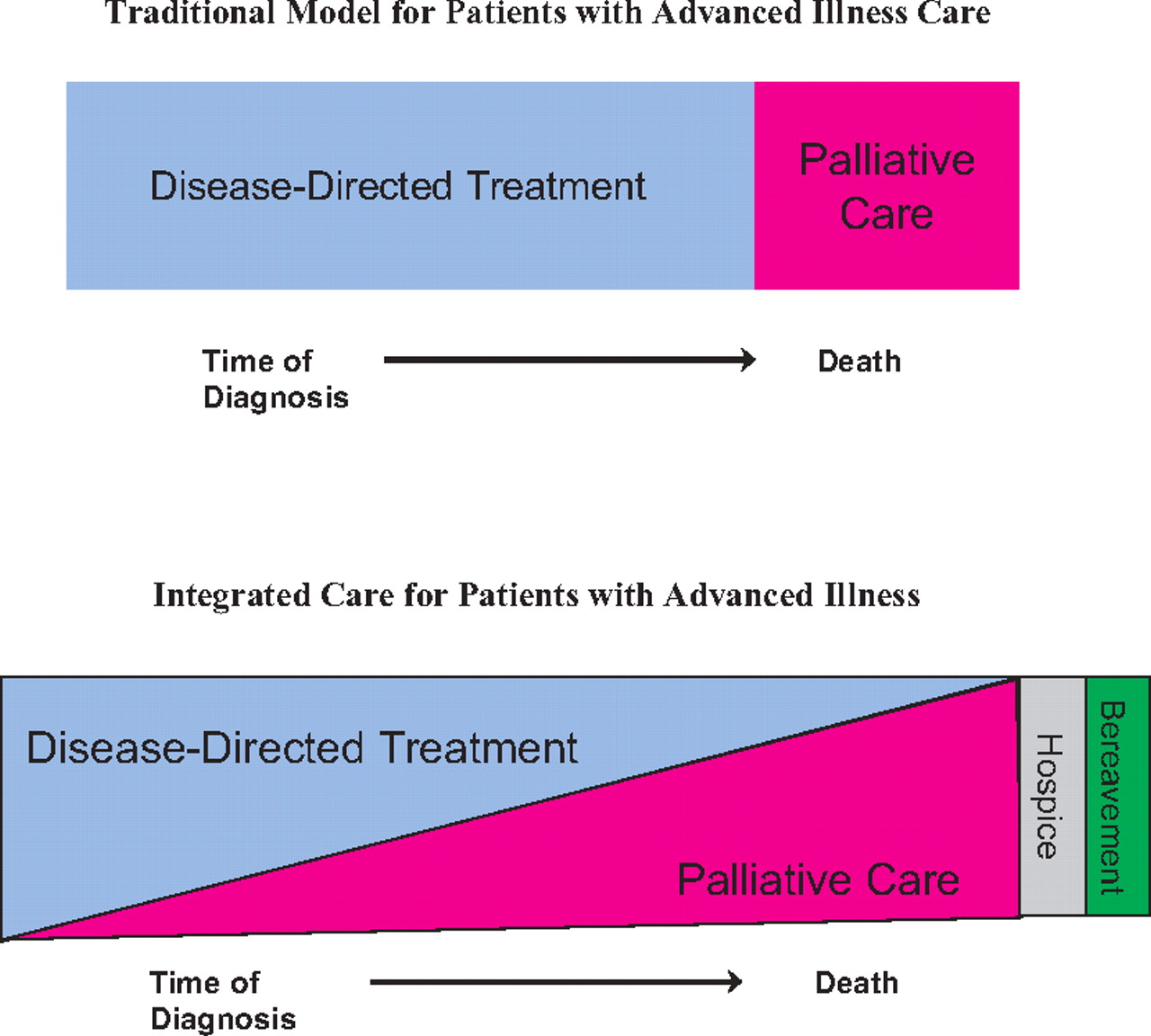

Over the past 10 years, clinical guidelines for the provision of palliative care have been developed by a variety of organizations. The National Consensus Standards for Quality Palliative Care (

33) and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (

34) have promulgated recommendations for patients with advanced disease. Whereas past practice has incorporated hospice or palliative care only when curative or disease-modifying treatments have failed, contemporary palliative care practice integrates palliative care principles and approaches from the time of diagnosis with a life-threatening illness as demonstrated in

Figure 1.

THE ROLE OF THE PSYCHIATRIST

The differential diagnostic issues for mental health disorders in the setting of advanced illness are challenging because of the contribution of medical symptoms and comorbidities, complex drug regimens, and psychological issues; psychiatrists play an invaluable role in helping palliative care teams tease out these interactions and in developing a rational approach to management. In addition, psychiatrists can play a role in helping palliative care teams understand and develop treatment plans for patients with personality and substance abuse disorders, as well as those with major mental illness and psychiatric disorders that may compromise decision making. As nonpsychiatrically trained physicians, most palliative care physicians benefit from collaboration with a psychiatrist who is able to teach them about management of these challenging patients. Understanding loss and grief is a key competency for palliative care clinicians; many psychotherapies deal centrally with loss, and our comfort in working with patients dealing with other losses can be a valuable resource in helping a palliative care team learn how to deal with intense suffering from the losses of advanced illness. Further, the psychiatrist can often play an important role in facilitating team reflection about their experiences in caring for patients who are dying and in supporting effective self-care strategies for their palliative care colleagues. Many of the elements of psychotherapy—intense, engaged, empathic listening to the words and the emotional “music” beneath the words, attention to process, cognitive behavior techniques such as reframing and problem solving, the ability to tolerate intense affect, skills in deepening the encounter and moving toward intense affect, and self-reflection focused on countertransference issues—are essential competencies for palliative care clinicians and are supported by the presence of a psychiatrist on the team, as well as explicit teaching about these issues. Issues that arise infrequently, including, in particular, requests for physician aid in dying, often arouse intense emotions within the team, present challenging clinical issues, and can be stimuli for reflection and exploration of issues of suffering; psychiatrists can play a key role in helping the team work through these issues.

BARRIERS TO PSYCHIATRISTS' INVOLVEMENT WITH PALLIATIVE CARE

Although psychosocial care and communication represent two of the most critical elements of excellent palliative care practice and education, psychiatry has been sparsely represented in the palliative care movement. Yet, many of the most challenging clinical problems in the field are those about which psychiatrists could have much to offer: how do patients move from denial and fear to a state of peace and acceptance of approaching death? How is depression best recognized and treated in the setting of terminal illness? How do patients and their families process and “metabolize” loss? Do drugs help? Is the desire for PAS a manifestation of psychopathology or a healthy adaptive response? How does repeated exposure to death and loss affect health care professionals?

Psychosomatic medicine/medical psychiatry services, in most settings, have little interaction with palliative medicine and tend to focus on diagnosis and treatment of disorders such as depression and delirium in the hospital setting, rather than the broad range of illness-related concerns that may be associated with a life-threatening illness. Most of the psychosocial care and teaching within palliative care clinical programs is carried out by social workers; few palliative care programs include psychiatrists.

Yalom (

35) and others have observed that psychiatrists tend to avoid dealing with death-related issues within themselves and with their patients. Psychiatric training offers trainees very limited exposure to the theories about response to loss, few opportunities to work longitudinally with patients with serious medical illness and their families, limited exposure to bereavement issues, and a growing focus on diagnosis and pharmacotherapy. Whereas palliative care focuses on identifying strengths and inner resources that help patients traverse this challenging developmental phase, psychiatry training emphasizes psychopathology. Reimbursement for palliative care and for psychiatry are poor, making it difficult to support a psychiatrist's work with the team.

QUESTIONS AND CONTROVERSY

Palliative care services, through attention to better pain management, improved communication about patients' desires for end-of-life care, enhanced emotional support for families struggling with intense feelings of grief and loss, and attention to palliative care needs across the continuum of care from home to hospital, may have a role to play as a clinical and preventive arm of medical ethics. Armed with medications (e.g., opioids for pain) and “procedures” (e.g., structured family meeting and goals of care conversation), palliative care clinical teams may be able to proactively avert conflict and moral distress through the provision of expert clinical care, leading to improved outcomes for patients, families, and clinicians. However, even with the best clinical care, ethical controversies will remain a feature of end-of-life clinical practice. Issues of futility, the role of physician-assisted dying in end-of-life care, the appropriate use of palliative sedation for intractable suffering, the role of artificial hydration and nutrition in patients with advanced dementia and other neurologic disorders, appropriate end-of-life decision making for vulnerable patients, and access to palliative care remain unresolved areas of conflict with both practical and moral implications. Furthermore, we will be challenged to find a therapeutic stance that acknowledges that suffering is an inevitable feature of advanced illness, but that it can be mitigated, often dramatically, through the use of cutting-edge comprehensive palliative care approaches.

Recent research has begun to illuminate the role of key psychological phenomena in influencing care choices and outcomes for patients with life-threatening illnesses. The impact of depression on treatment choices, the effects of physician communication on patients' psychological well-being at the end of life, how care of the patient before death affects bereavement outcomes, new approaches to facilitating dignity and peace at the end of life, and the impact of psychological factors in physicians on care they provide to patients remain important questions about the care of persons in the last phase of life. These questions also have implications for how we train physicians to care for patients with advanced illness, the use of aggressive medical treatments at the end of life, preventive interventions for the bereaved, and the role of psychosocial treatments in promoting quality of life in the setting of advanced illness.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Patients cared for in our health care system should be able to expect that they will receive high-quality palliative care, along with excellent disease-directed management for a life-threatening illness. In 2007, with Hospice and Palliative Medicine now a recognized subspecialty, clinicians in all disciplines, including psychiatry, should have a basic familiarity with the principles and approach of palliative care. As psychiatrists, we have a responsibility to advocate the inclusion of basic competencies in psychosocial care at the end of life into expectations for this emerging subspecialty. Finally, we should contribute to the expansion of the knowledge base and the clinical management options for patients dealing with complex psychiatric issues at the end of life.