Panic disorder is a common psychiatric disorder that affects up to 5% of the population at some point in their lifetime (

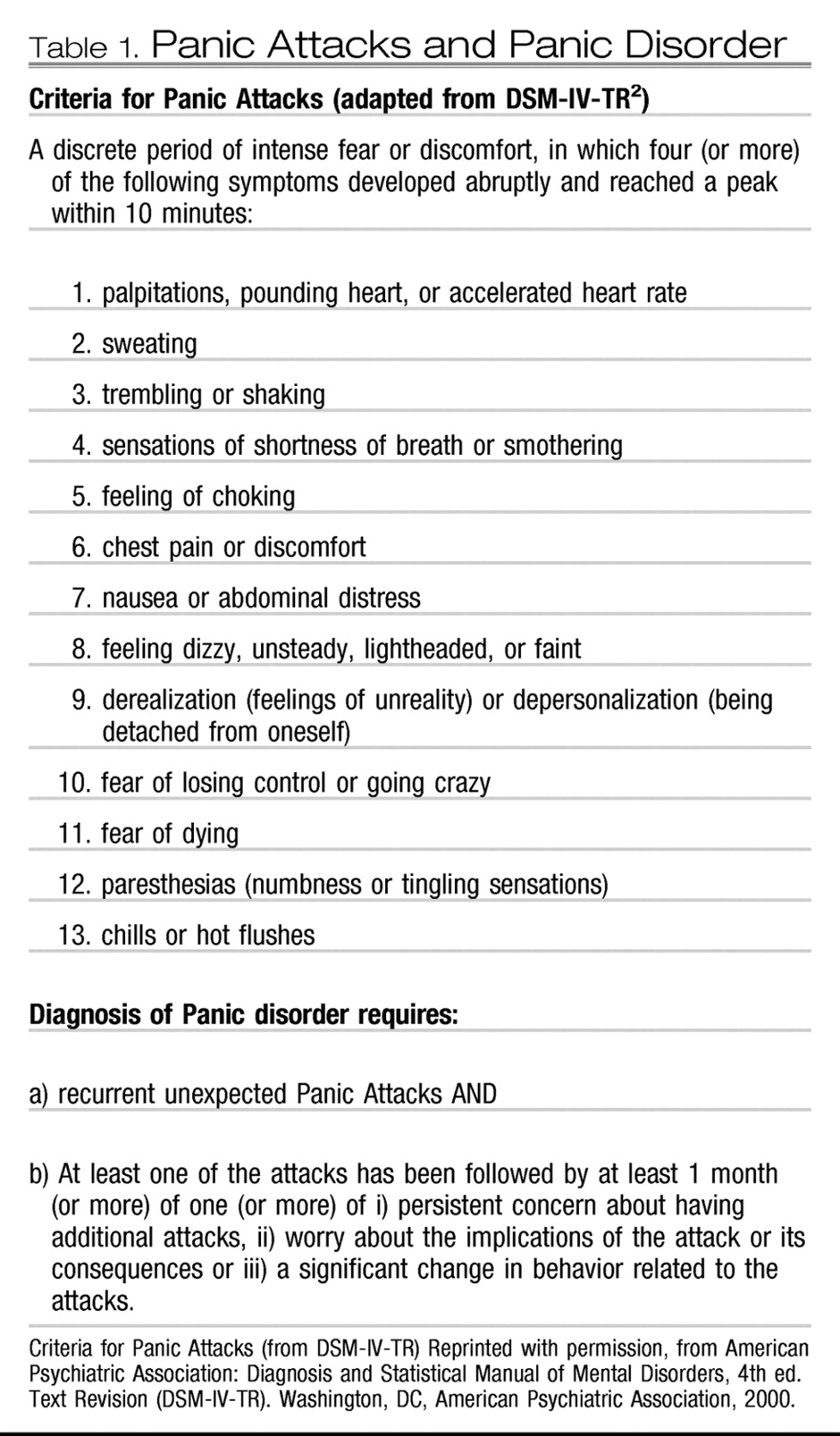

1). The essential features of panic disorder include recurrent, often unexpected, panic attacks followed by at least 1 month of persistent concern about having another panic attack, worry about the possible implications or consequences of the panic attacks, or a significant behavioral change related to the attacks (

2). Panic attacks are discrete episodes associated with an intense fear or discomfort and accompanied by at least 4 of the 13 somatic or cognitive symptoms listed in the DSM-IV-TR: accelerated heart rate, shortness of breath, chest pain, choking sensations, hot/cold flashes, sweating, trembling, nausea, depersonalization/derealization, fear of dying, fear of going crazy, and fear of losing control (

Table 1) (

3). Panic attacks usually have an abrupt onset and last from 10 to 45 minutes (

4). Many times, these may result in behavioral modifications in daily routine. Although panic attacks can occur in associated anxiety disorders including phobias and social anxiety disorder, panic attacks associated with panic disorder are unique as they occur spontaneously without an environmental trigger. Panic disorder may be associated with agoraphobia if the individual avoids places or situations from which escape may be difficult (

5).

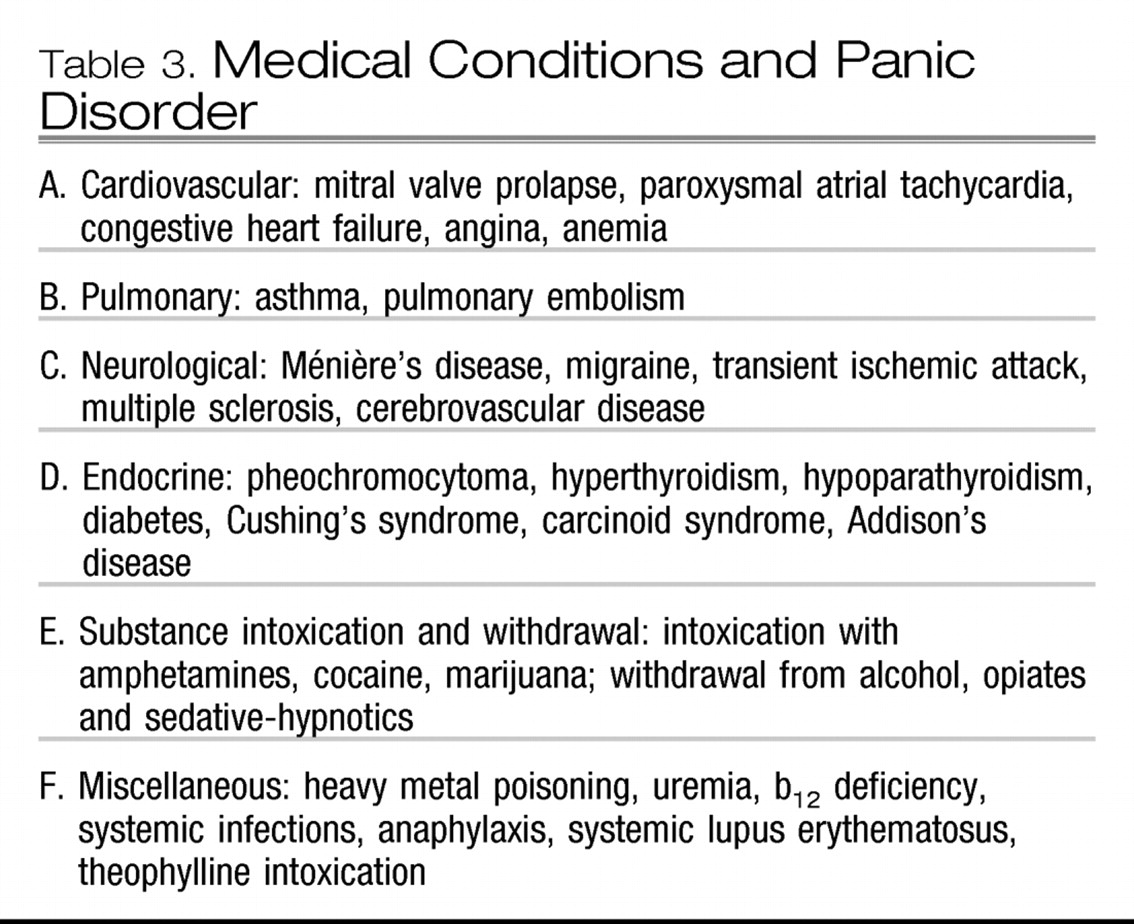

Panic disorder must be distinguished from various psychiatric disorders and physical conditions that can have associated panic symptoms. Some of these conditions include other anxiety disorders (including specific phobias and posttraumatic stress disorder), substance use disorders (including stimulant abuse or withdrawal from sedative agents), or medical conditions, including hyperthyroidism (

6). Furthermore, the clinical presentation of panic disorder may vary depending on the age of presentation and may make it difficult for the clinician to assess and ascertain the significance of such symptoms (

7). This article focuses on the distinct diagnostic dilemmas and assessment tools used in the evaluation of panic disorder across the lifespan. A discussion of treatment approaches for panic disorder is beyond the scope of this article, and the reader is referred elsewhere for such a discussion (

8). The paucity of literature on this subject in both extremes of ages further limits the evidence base in these age groups. As a result, there are a few instances in this article where the author has to refer to a more general term, “anxiety disorder,” instead of panic disorder specifically.

ASSESSMENT IN CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS

Although panic disorder is believed to emerge in late adolescence or early adulthood, adults with panic disorder often report having had panic symptoms starting in childhood or early adolescence (

9). In most such individuals panic disorder may have either been misdiagnosed or not come to clinical attention. Epidemiological studies have reported that panic attacks may not be rare in the community samples of adolescents, although panic disorder may not be commonly reported. For instance, Goodwin and Gotlib (

10) reported a prevalence of 3.3% of panic attacks from among 1,285 youth, aged 9–17 years, whereas Whitaker et al. (

11) reported lifetime prevalence of panic disorder to be 0.6% using a structured interview with 5,000 students aged 14–17 years. A much higher prevalence of panic disorder has, however, been reported in the clinical samples. Biederman et al. (

12) reported that 6% of the children and adolescents consecutively referred to their pediatric psychopharmacology clinic met the criteria for panic disorder. Similarly, Masi et al. (

13) found that 10.4% of their consecutive outpatients referred to a mood and anxiety service had panic disorder.

Clinical presentation of panic symptoms in younger children compared with that in adolescents can be intriguing (

14). Such a presentation can be manifested by the presence of atypical symptoms including “hyperventilation syndrome,” nocturnal occurrences, and fewer somatic and cognitive symptoms (

15). Still, some of the common symptoms in younger children include palpitations, shortness of breath, sweating, faintness, and weakness (

16). Among adolescents, symptoms such as chest pain, trembling, headache, and vertigo are reported (

17). Another interesting developmental difference between the two age groups is that children and younger adolescents may attribute their symptoms to the external environment compared with older adolescents. Older adolescents are more competent of internal attributions that are more typically seen with panic disorder. Furthermore, cognitive symptoms appear only among adolescents (

18). Interestingly, the fear of dying has been reported to be the earliest cognitive symptom whereas feelings of losing control and symptoms of depersonalization and derealization appear later (

15,

17). Given the complexity of establishing a diagnosis of panic disorder in this population, the clinician may benefit by using brief self-reports and rating scales for anxiety disorders, some of which are even available for the preschool child.

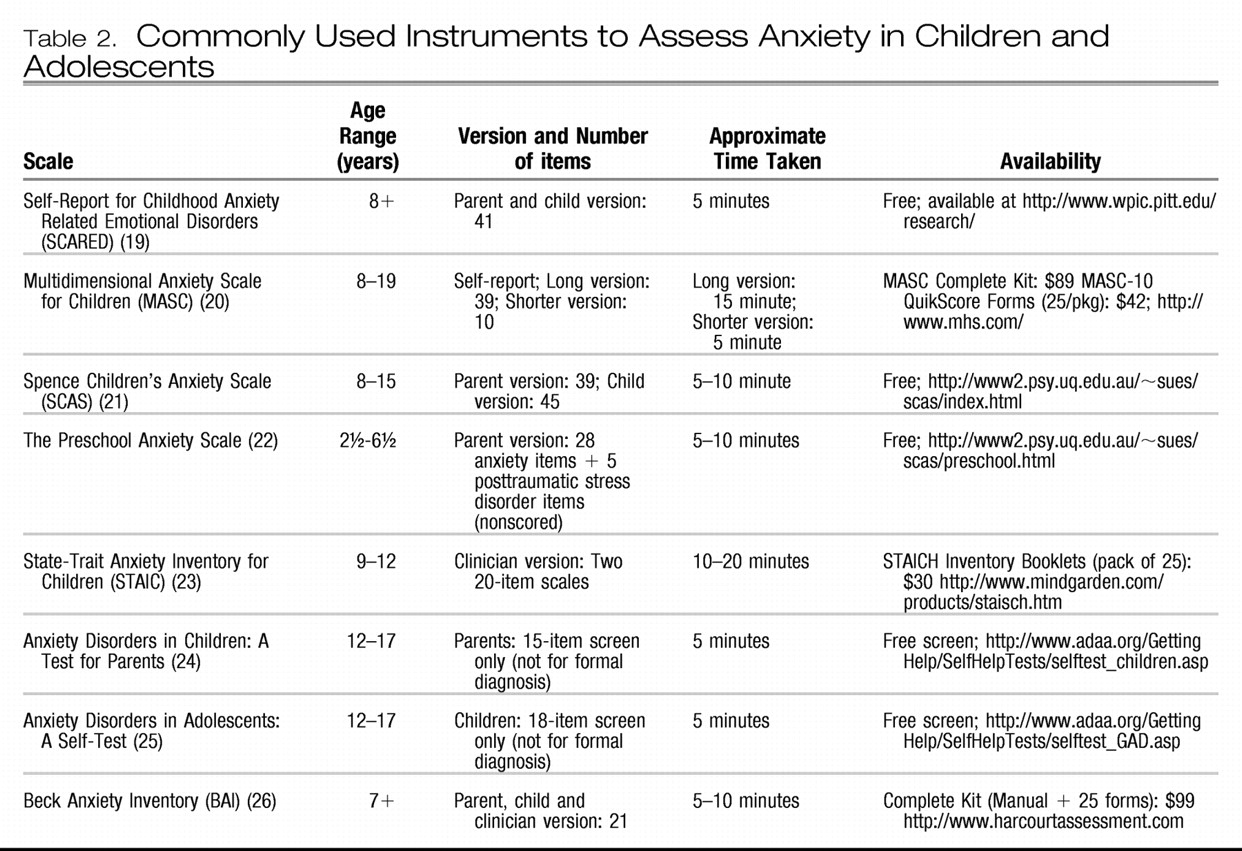

Table 2 lists some of the freely available assessment tools that include self-report, parent, and clinician versions.

Another interesting aspect in this age group is the association of panic symptoms with comorbid anxiety disorders including separation anxiety disorder and generalized anxiety disorder (

27,

28). Separation anxiety disorder has been reported to be associated with early-onset panic disorder but not necessarily with adult onset panic disorder (

29). Similarly, agoraphobia has been reported more frequently in younger-onset panic disorder (

30). Furthermore, mitral valve prolapse has also been associated with a higher incidence of panic disorder in the adolescent population (

31). The clinician should also rule out any medical causes (such as pheochromocytoma and thyroid disease) and substance use disorders, both of which are well known to imitate panic disorder. More details are considered in the next section. Along with these comorbidities, a strong family history of panic disorder should cue the clinician to perform a detailed assessment for panic disorder in the child. Awareness of early-onset panic disorder and a detailed assessment can potentially improve diagnosis and treatment and thus decrease impairment and improve quality of life for these patients.

The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry practice parameter for anxiety disorders also provides recommendations for assessment of various anxiety disorders. Although not specifically discussing panic disorder, the practice parameter recommends that clinicians routinely include screening questions about anxiety symptoms and that the questions should use developmentally appropriate language based on DSM-IV-TR criteria. If the screening indicates significant anxiety, the clinician should thoroughly evaluate the patient to determine the type, nature, frequency, and severity of the anxiety disorder and assess the functional impairment caused by it. Clinicians may also find it beneficial to use sections of the available diagnostic interviews such as the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV-Child Version (ADIS). The ADIS has a Feelings Thermometer (ratings from 0 to 8) that may help children quantify and self-monitor ratings of fear and interference with functioning. Younger children may use more developmentally appropriate visual analogs such as smiley faces and upset faces to rate severity and interference (

32).

ASSESSMENT IN THE ELDERLY

There is very limited literature on the subject of panic disorder in the geriatric population. As a result, most recommendations regarding assessment of panic disorder are derived and extrapolated from the adult literature. Flint et al. (

47) have reported a decline in panic attacks in elderly individuals; however, it is important not to dismiss the significance of such anxiety symptoms in this population. Although the diagnostic criteria of panic disorder are similar to those in the general adult population, its presentation may vary in elderly individuals. Panic attacks in this population may be more reactive to transient situations or life changes (

48). Many times elderly individuals may not complain of anxiety symptoms but focus on physical symptoms (

49). They may not elaborate on their subjective apprehensive states but rather discuss bodily dysfunction. These complaints can force the clinician to delve into extensive medical investigations when the etiology may be more functional. On the contrary, because elderly individuals are more predisposed to having a medical comorbidity, it is imperative not to dismiss their physical complaints either. As a result, panic disorder has not been very well studied and more research on the subject is needed.

Apart from the variability in quality of symptoms for panic disorder in this population, the frequency and severity of reporting of symptoms may vary as well. Sheikh et al. (

50) reported that elderly individuals with panic disorder report less severe and fewer panic symptoms, less anxiety and arousal, and higher levels of functioning compared to middle-aged patients with panic disorder. Furthermore, elderly patients with late-onset panic disorder may report less distress with panic symptoms compared with older patients with early-onset panic disorder (

50). It may take quite a few panic attacks along with insignificant laboratory results in elderly patients to lead to a diagnosis of panic disorder. The medical comorbidities that may present with panic-like symptoms are similar to those mentioned in the adult population as listed in

Table 3 and should be thoroughly assessed, especially in this older population.

To the best of the author's knowledge, there are no specific rating scales available for assessment of severity and diagnosis of panic disorder in the geriatric population, especially because panic disorder has not been very well studied in this age group and possibly also owing to a decline in panic attacks in the population. One of the newly developed scales, the Geriatric Anxiety Inventory (GAI) has recently been shown to measure common symptoms of anxiety in older adults. It consists of 20 items that can be answered in a dichotomous manner, which is “agree/disagree.” The GAI can be self-rated or administered by a trained health professional. The GAI, however, was not designed to diagnose specific anxiety disorders but rather to assess the severity of anxiety symptoms across a range of presentations in older adults (

51). Clinicians also use some other assessment tools such as the Hamilton Anxiety Scale and Beck Anxiety Inventory for monitoring the anxiety symptoms that are often comorbid with both psychiatric and medical conditions. It is important to recognize and treat such comorbid anxiety disorders as they can have a significant impact on the quality of life in this population. In fact, it has been reported that such patients may also have a much increased risk of both suicidal attempts and completed suicides (

52). In addition, there is also some evidence to suggest that late-onset panic attacks may be due to preexisting depression (

48). Furthermore, anxiety may also be a predictor of decline in cognitive functions, which should be simultaneously evaluated (

53).

The diagnosis of panic disorder is based on a thorough history (from both the patient and the patient's family or caregivers), mental state examination, physical examination, and investigations selected to screen for medical etiology that could be contributing to symptoms. Initial screening investigations may include a complete blood count, fasting serum glucose level, serum calcium level, thyroid function tests, and an ECG. Physicians should have a high index of suspicion for panic attacks in older patients with multiple episodic physical symptoms that are not explained by physical examination and investigations. In addition, symptoms such as derealization, depersonalization, and fear of losing control should also alert the clinician to the possibility of panic disorder.