Epidemiology.

Asthma is a chronic lung condition characterized by episodic inflammation and small airway constriction that can occur in response to environmental and other triggers. More than 30 million Americans have asthma, of whom 30% are children under the age of 18. Asthma ranges in severity from mild to life-threatening with an intermittent or persistent course. Age-adjusted mortality in 2003 was 1.4/100,000 population, with higher rates in African-Americans, women and the elderly. The prevalence of asthma has increased substantially over the past several decades, making it the most common chronic disease among youth worldwide, though the causes of this increase are unknown. Although death rates are stabilizing or decreasing, possibly due to improvements in medical care, asthma continues to pose a substantial economic burden. The total cost of asthma in 2004 was US$16 billion, US$11.5 billion due to direct healthcare costs (including US$5 billion in prescription drug costs) and US$4.6 billion in indirect costs associated with lost productivity at work and school and mortality (

60). While there is no cure for asthma, the vast majority of persons with asthma can live symptom-free and without functional impairment with adequate routine medical care and adherence to asthma treatment. Yet, poor asthma control remains a problem among a substantial proportion of the population. As such, ongoing research aims to identify factors associated with poor asthma control. Recent evidence suggests that mental disorders may play a role in various aspects of onset and course of asthma and are the subject of studies designed to better understand this relationship.

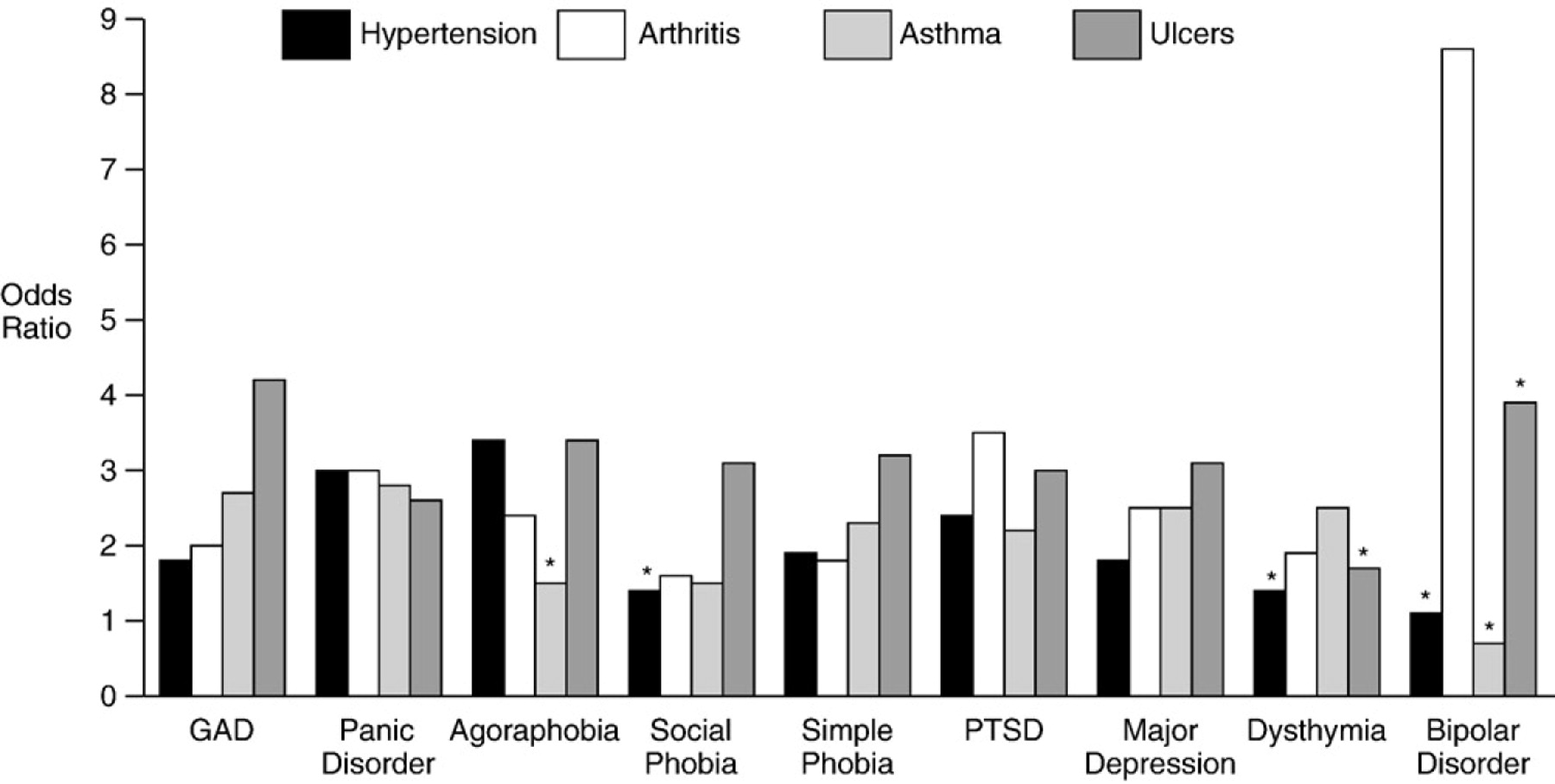

Findings from community-based epidemiologic studies in youth and adults demonstrate a strong and consistent association between asthma and anxiety disorders (

61–

66). In contrast, available evidence on the link between asthma and depression is somewhat mixed (

63,

67–

69). The majority of studies to date on the link between mental disorders and asthma have relied on patient self-reports or parental reports of asthma. However, one study that examined the relationship between physician-diagnosed asthma and mental disorders found that anxiety disorders were significantly associated with both nonsevere [OR: 1.51 (1.00–2.32);

P<.05) and severe asthma [OR: 2.09 (1.30–3.36);

P<.05] (

64), in contrast to the weaker and nonsignificant associations for mood disorders with lifetime nonsevere [OR: 1.44 (0.94–2.19)] or severe asthma [OR: 1.21 (0.75–1.98)]. Of note, nonsevere asthma (past 4 weeks) was significantly associated with increased likelihood of any affective disorder [OR: 2.42 (1.03–5.72);

P<.05], while bipolar disorder was very strongly associated with lifetime severe asthma [OR: 5.64 (1.95–16.35);

P<.05]. Panic disorder, panic attacks, GAD and phobias appear to be the anxiety disorders most strongly associated with asthma (

64). Another study compared 769 youth with physician-diagnosed asthma to 582 age-matched controls and found an approximately twofold increase in the prevalence of one or more anxiety or depressive disorders, with greater rates of anxiety compared to mood disorders, and a significant correlation between anxiety sensitivity and asthma severity (

70).

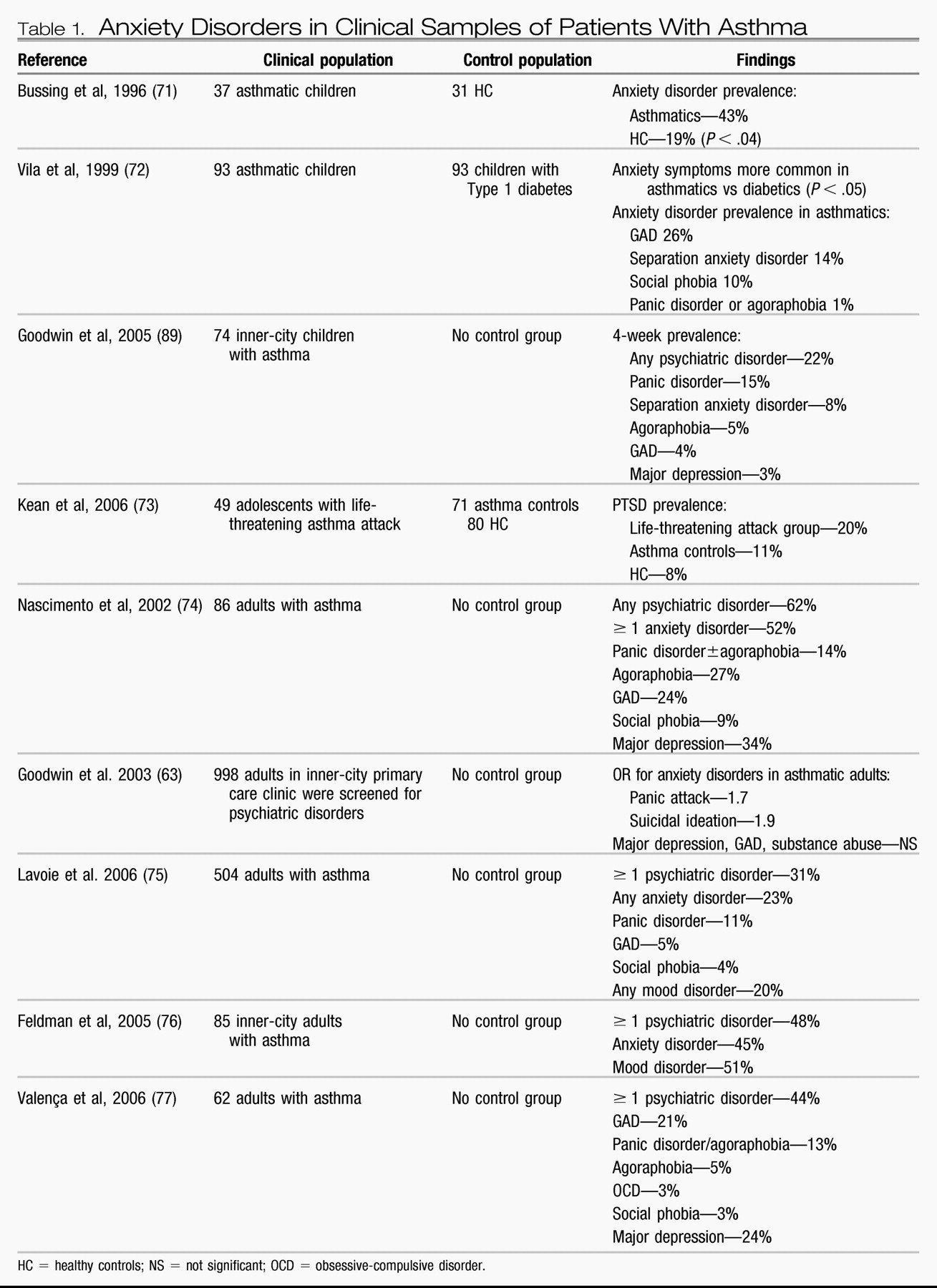

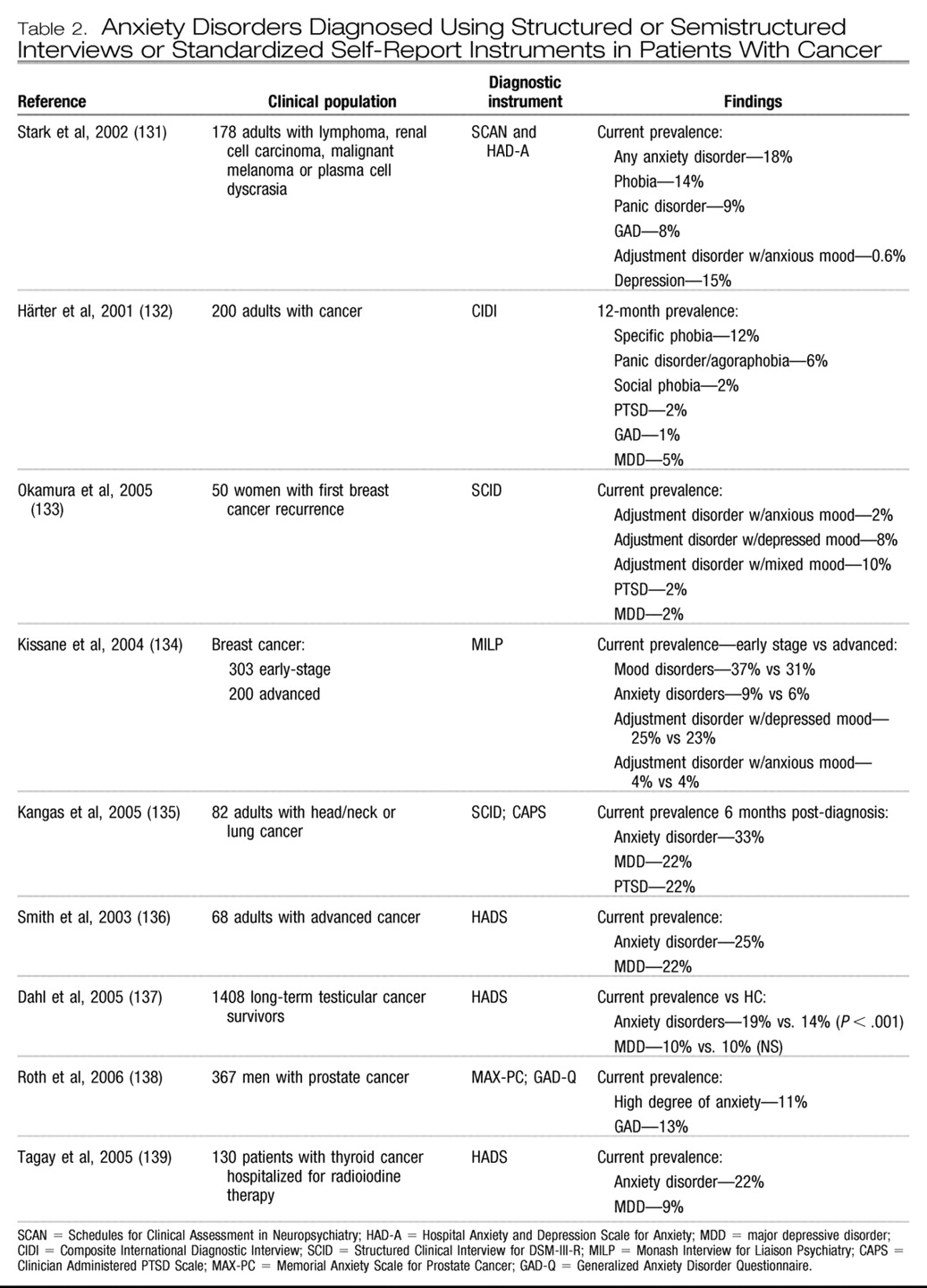

Clinical studies assessing the rates of mental disorders in patients with asthma, although largely limited to relatively small sample sizes and self-reported asthma status, have consistently found high rates of anxiety disorders in children, adolescents and adults (

Table 1). Few studies have been able to control for potentially confounding or mediating factors in the links between asthma and mental disorders, such as smoking or use of asthma medications (

78). One study found that adolescents with a history of life-threatening asthma attacks are more likely to have symptoms of PTSD, which was directly related to the life-threatening experiences associated with asthma, compared to less severely ill patients or healthy controls (

73). Another study examined the relationship between PTSD symptoms and asthma among male twins and found the association was not explained by common genetic factors (

79).

One study of adolescents with asthma found that, after controlling for severity of asthma, the presence of an anxiety or depressive disorder was associated with an increased number of days with asthma symptoms in the past 2 weeks (mean: 5.4 days) compared to adolescents without these psychiatric diagnoses (mean: 3.5 days;

P<.001), and that the number of anxiety-depressive symptoms was strongly associated with higher levels of asthma symptoms

(P <.001) (

80). The presence of anxiety disorders or other psychiatric diagnoses did not correlate with asthma severity in two studies of adult patients in asthma clinics (

76,

81) or one large, primary care-based study (

70). Findings for depression are somewhat equivocal, with some studies suggesting that depression is prevalent (

74–

77).

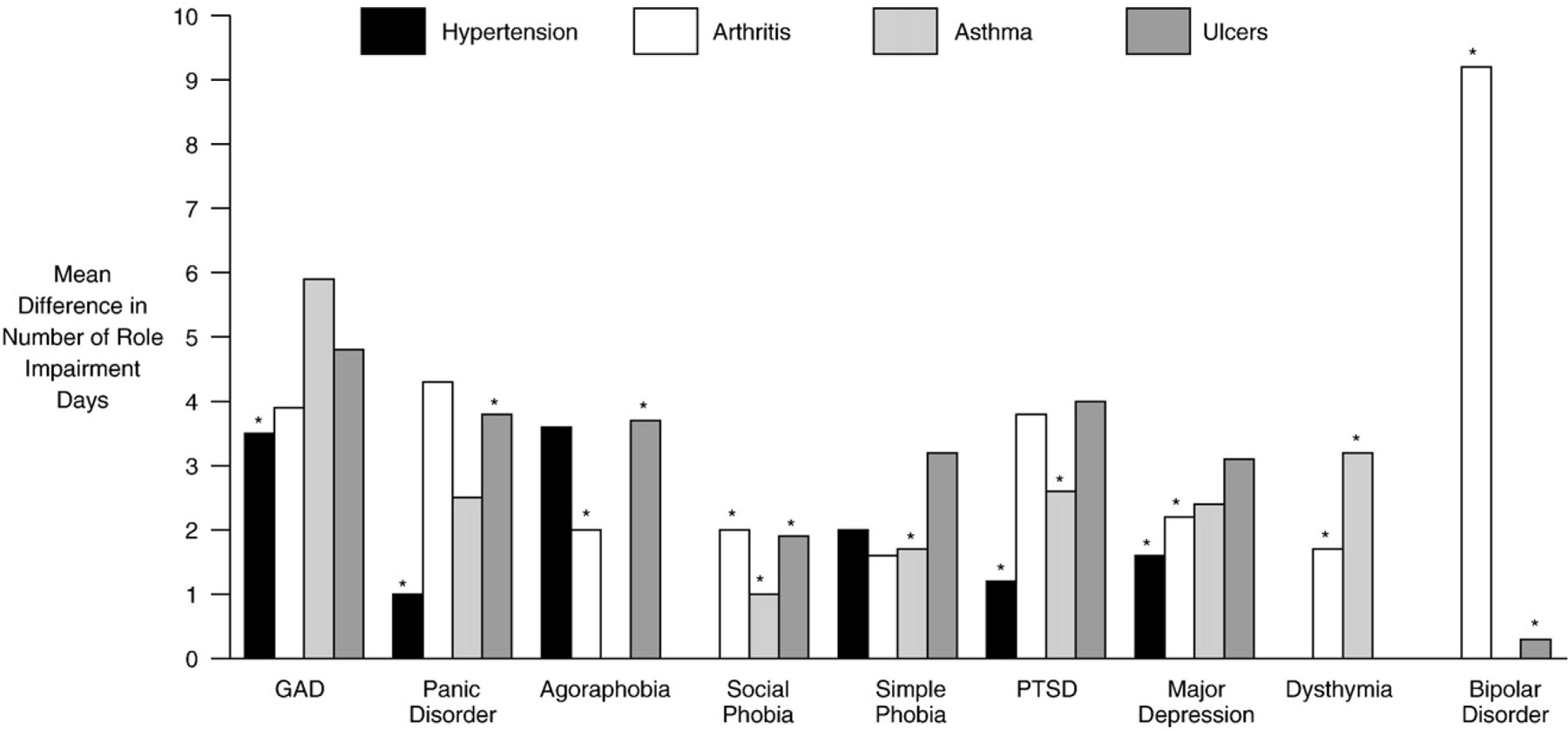

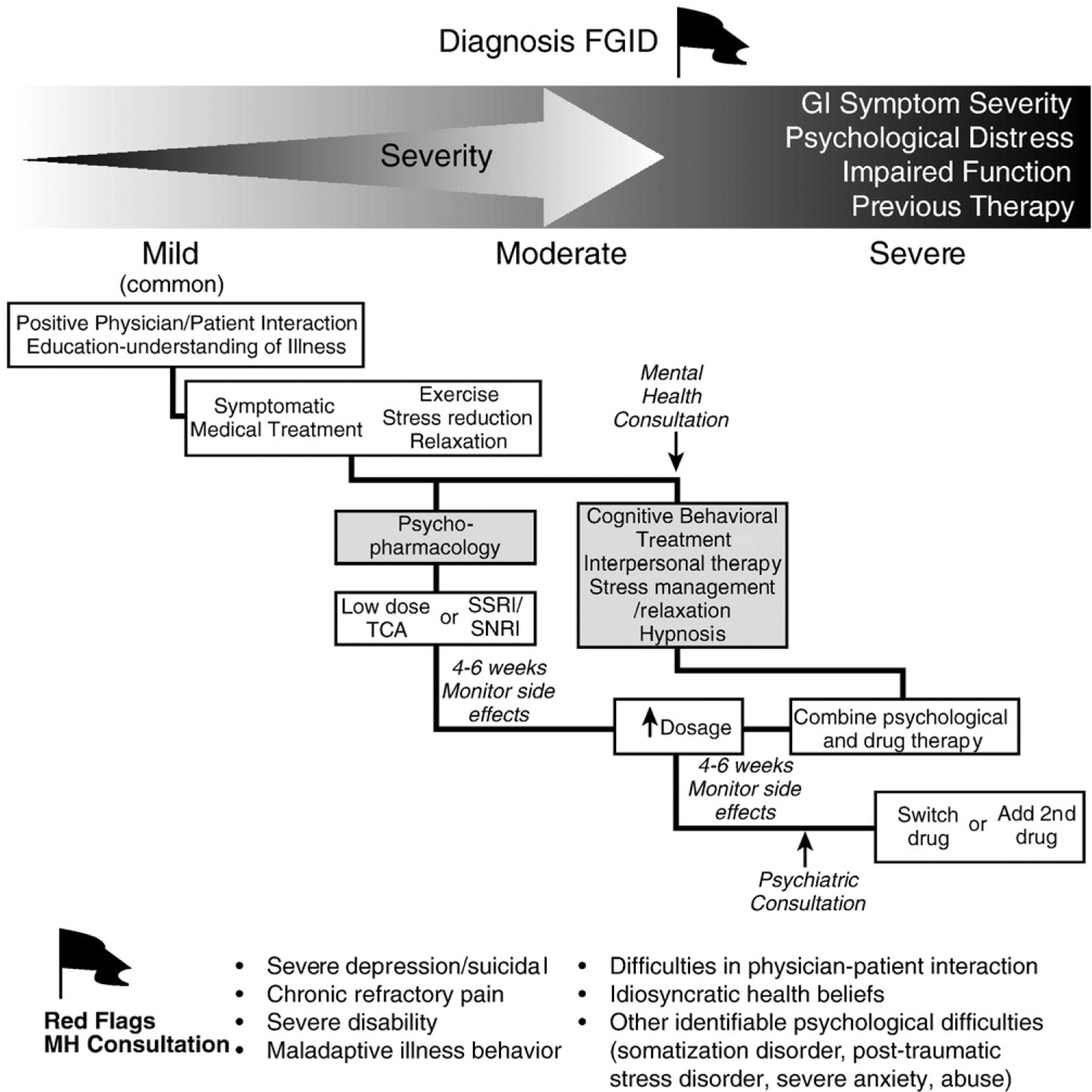

Nonetheless, poor asthma control, increased functional impairment, decreased quality of life, and utilization and cost of healthcare resources have been shown to be strongly associated with anxiety and mood disorders among persons with asthma (

80,

82). Patients with comorbid asthma plus anxiety or mood disorders are more likely to use bronchodilators in the previous week (

P<.02), have lower scores on asthma-control rating scales (

P<.001) (e.g., nocturnal waking, activity limitation, wheezing, increased use of asthma medications, pulmonary function tests) (

81) and lower quality of life as measured by activity limitation, asthma symptoms, environmental stimuli and emotional distress (

P<.001) (

81). Patients with asthma and a comorbid psychiatric diagnosis, including an anxiety disorder, are 4.9 times more likely to use an emergency room and 3.8 times more likely to be hospitalized (

76), but few patients are treated for their mental disorder (

81). Despite these robust data, comorbid anxiety and depressive disorders are only accurately diagnosed in approximately 40% of asthmatic patients in primary care (

83). There are also a number of clinical and community-based studies that have found links between asthma and suicidal ideation (

63,

84), suicide attempts and completed suicide (

84). As suicide behavior has also been linked with anxiety disorders (

85), further investigation into the risk of suicide behavior among individuals with asthma and anxiety disorders is needed.

Smoking is a particularly problematic health behavior in youth with asthma, leading to higher symptom burden and treatment resistance.

DSM-IV anxiety/depressive disorders in a sample of adolescent patients with asthma in one healthcare system have been found to be present in 14.5% of nonsmokers, 19.8% of susceptible nonsmokers and 37.8% of smokers. After controlling for several covariates, youth with comorbid anxiety and depressive disorders and asthma had a two-fold increased likelihood of smoking compared to those without. Youth with asthma who smoked reported significantly more asthma symptoms, reduced functioning due to asthma, less use of controller medication and more use of rescue medications compared to those who did not smoke (

86).

Pathophysiology.

The mechanisms underlying the association between asthma and anxiety disorders are not known. It may be that there is a causal link between asthma and anxiety disorders; yet, increasingly, evidence supports the possibility that one or more outside factors, either environmental or genetic, may influence the risk of both (

87). One longitudinal study that tracked children from ages 3 through 18 and assessed temperamental and illness factors found that a history of self-reported poor respiratory health at age 15 predicted panic disorder/agoraphobia at ages 18 to 21 compared to participants without a history of respiratory problems (

88). Another longitudinal, community-based study followed 591 young adults for 20 years, beginning at age 19, and examined the relationship between asthma and panic disorder (

65). A bidirectional relationship was observed in which asthma predicted onset of later panic disorder, and panic disorder was antecedent to active asthma. Childhood anxiety, parental smoking and a family history of allergy have been suggested as possible shared etiologic factors in both asthma (

65) and panic disorder (

89). Environmental factors including low socioeconomic status, exposure to pollutants, environmental stressors and childhood adversity may predispose youth to both asthma and anxiety and depressive disorders (

78). Potential factors that could play a role in causal mechanisms for the relationship between asthma and panic disorder include increased levels of anxiety associated with fear of the next asthma attack, the anxiogenic properties of asthma medications, hyperventilation associated with panic attacks, and poor adherence to asthma treatment in patients with psychiatric diagnoses (

65,

78).