Anxiety disorders are more common than any other major group of diagnoses, with the exception of substance use disorders. According to the National Comorbidity Survey, the overall lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders is 24.9%, including rates of 3.5%, 13.3%, 5.1%, for panic disorder with or without agoraphobia, social phobia, and generalized anxiety disorder, respectively (

1). The effects of these disorders on both physical health and occupational functioning have been well documented (

2–

6). In the WHO Collaborative Study on Psychological Problems in General Health Care, more than one-half of the patients with panic disorder without or with agoraphobia reported moderate to severe occupational dysfunction and physical disability (

3). The severity of disability reported was similar to that reported for depressive episodes and higher than that for alcohol dependence.

METHOD

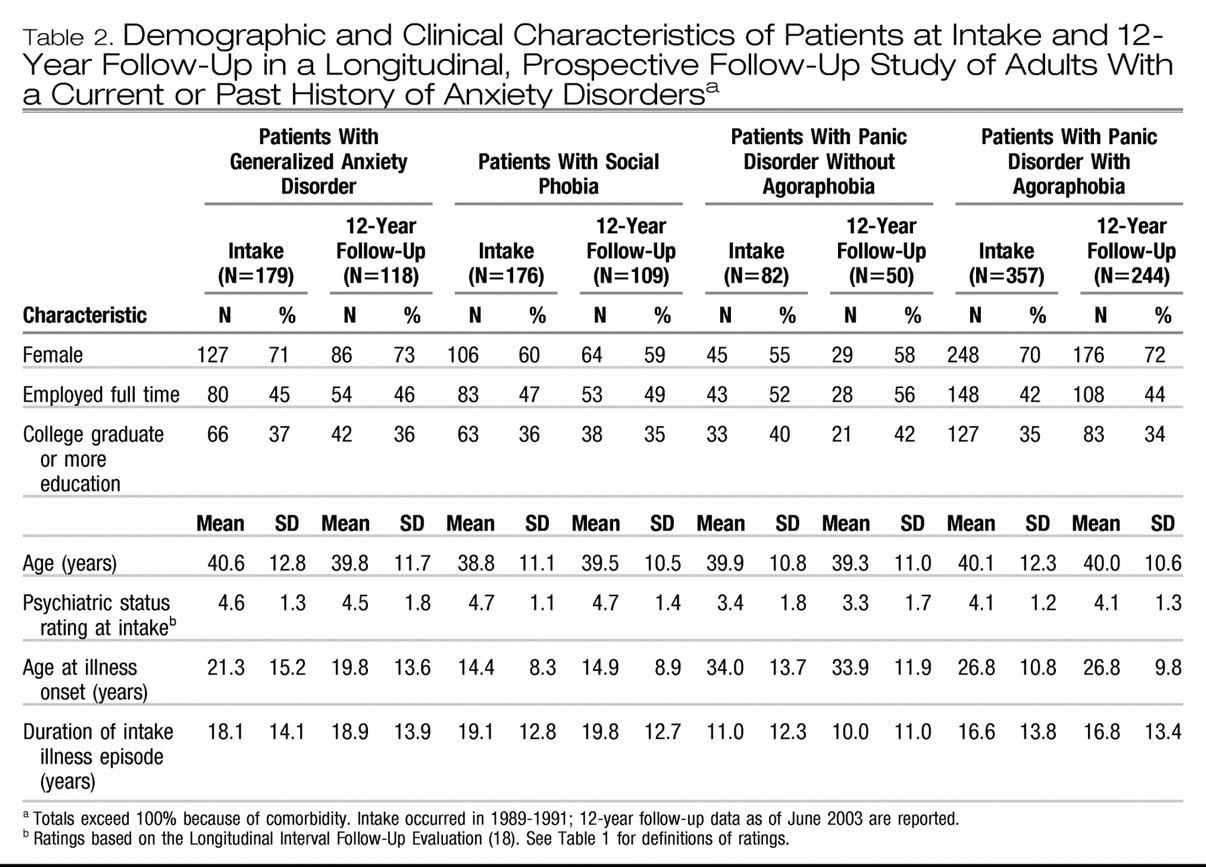

The Harvard/Brown Anxiety Disorders Research Program is a longitudinal, prospective, short-interval follow-up study of adults with a current or past history of anxiety disorders. In 1989-1991, 711 participants entered this study from more than 30 clinicians' practices at 11 clinical treatment facilities in the New England area. These methods are described in detail elsewhere (

17). The primary inclusion criterion was a past or current diagnosis of any of the following disorders at intake: panic disorder without agoraphobia, panic disorder with agoraphobia, social phobia, and generalized anxiety disorder.

Insufficient for inclusion, but frequently seen as comorbid conditions, were diagnoses of simple phobia, posttraumatic stress disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and anxiety disorder not otherwise specified. Participants were required to be at least age 18 years at intake, willing to voluntarily participate in the study, and willing to sign a written consent form. Exclusion criteria consisted of the presence of an organic brain syndrome, a history of schizophrenia, and current psychosis at intake; otherwise, any comorbidity was allowed.

PROCEDURES

The data for the study reported here were derived from the structured diagnostic interview administered at intake and from subsequent follow-up interviews over 12 years. In the initial comprehensive evaluation, lifetime history was assessed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Non-Affective Disorders, Patient Version, and the Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia—Lifetime Version (SADS-L) (

18). Items on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Non-Affective Disorders, Patient Version, and SADS-L were combined to create the SCALUP, a structured interview used to assess diagnoses at intake (available on request from Dr. Keller, Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, Brown University). The instrument yielded both present and past RDC diagnoses for affective disorders and DSM-III-R diagnoses for nonaffective (including anxiety) disorders. Interviews were conducted by trained, experienced bachelor's- and master's-level clinical interviewers and usually took place in single sessions lasting 2–4 hours.

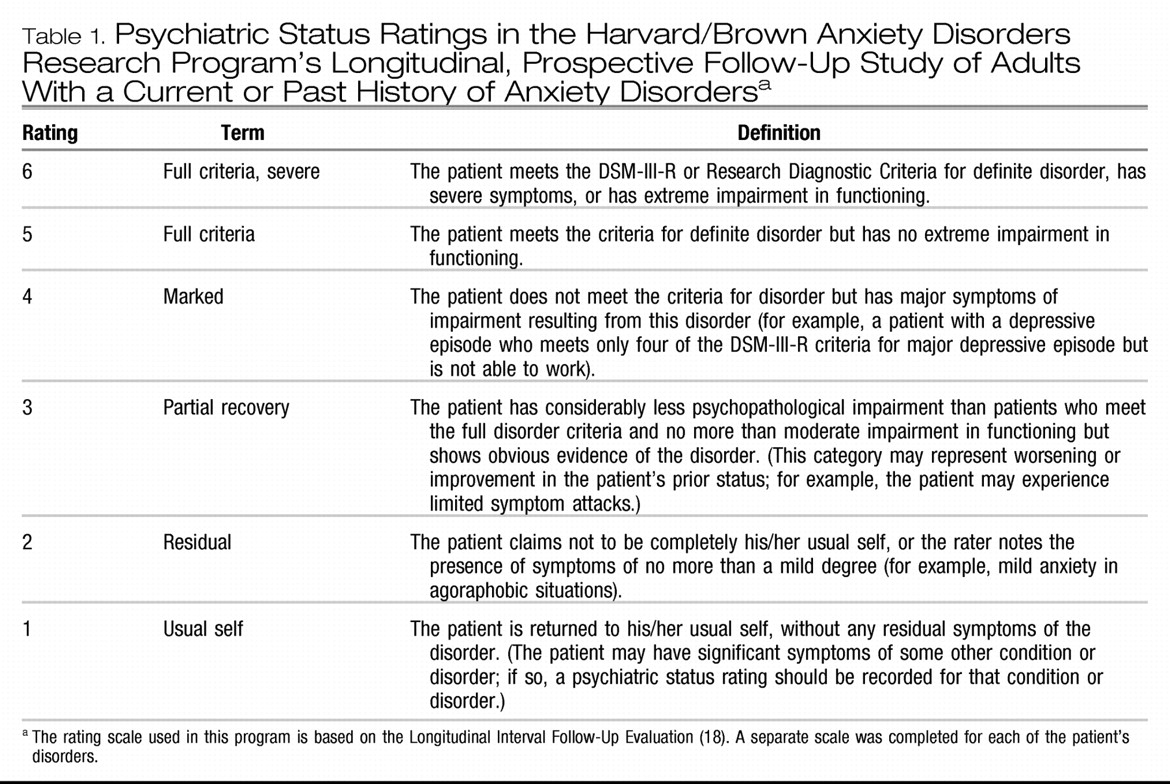

Follow-up interviews were conducted at 6-month intervals for the first 2 years, annually for years 3–6, and every 6 months in years 7–12. These interviews utilized the Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation (

19), which is used to assess the weekly course of disorders with psychiatric status ratings (

Table 1). For a rating of the greatest severity of illness (psychiatric status rating of 6), the respondent was required to meet the full DSM-III-R criteria for the disorder in addition to having severely disrupted functioning. A psychiatric status rating of 1 indicates an absence of symptoms. In addition, the Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation was used to collect information on pharmacological treatment for each week during the interval, including information on the type of medication and average daily dose.

Reliability and validity studies of the Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation found good to excellent agreement on psychiatric status rating scores. Interrater reliability was measured with intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs); ICCs for each of the disorders were as follows: 0.67–0.88 for panic disorder, 0.78–0.86 for generalized anxiety disorder, 0.75–0.86 for social phobia, and 0.73–0.74 for major depressive disorder (

20). Long-term test-retest reliability over 1 year was also found to be very good to excellent for the anxiety disorders and for major depressive disorder. A separate external validity assessment comparing psychiatric status ratings with other psychosocial measures found good concurrent and discriminant validity (

20).

DEFINITIONS OF RECOVERY AND RECURRENCE

Recovery and recurrence in this study were defined prospectively. A participant was considered to have recovered from anxiety disorder if he/she experienced 8 consecutive weeks at psychiatric status ratings of 2 or less (

Table 1). Subjects who met this condition were virtually asymptomatic for 2 consecutive months. This definition of recovery has been widely used in studies of affective disorders and other disorders. For each disorder besides generalized anxiety disorder, recurrence was defined as the onset of symptoms at a psychiatric status rating level of 5 or greater for 2 consecutive weeks following a recovery (

Table 1). For generalized anxiety disorder, recurrence was defined as the onset of symptoms at a psychiatric status rating of 5 or greater for 6 months following a recovery.

STATISTICAL ANALYSES

Statistical analyses were conducted with SAS Version 6.07 (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.). Probabilities of recovery and recurrence were calculated by using standard survival analysis methods. Kaplan-Meier life tables were constructed for time to recovery and time to recurrence. Data for patients who were lost to follow-up were censored at the time of dropping out of the study. Proportional hazards regression analyses with time-varying covariates were conducted to determine risk ratios for possible comorbid psychiatric predictors of recovery and recurrence.

DISCUSSION

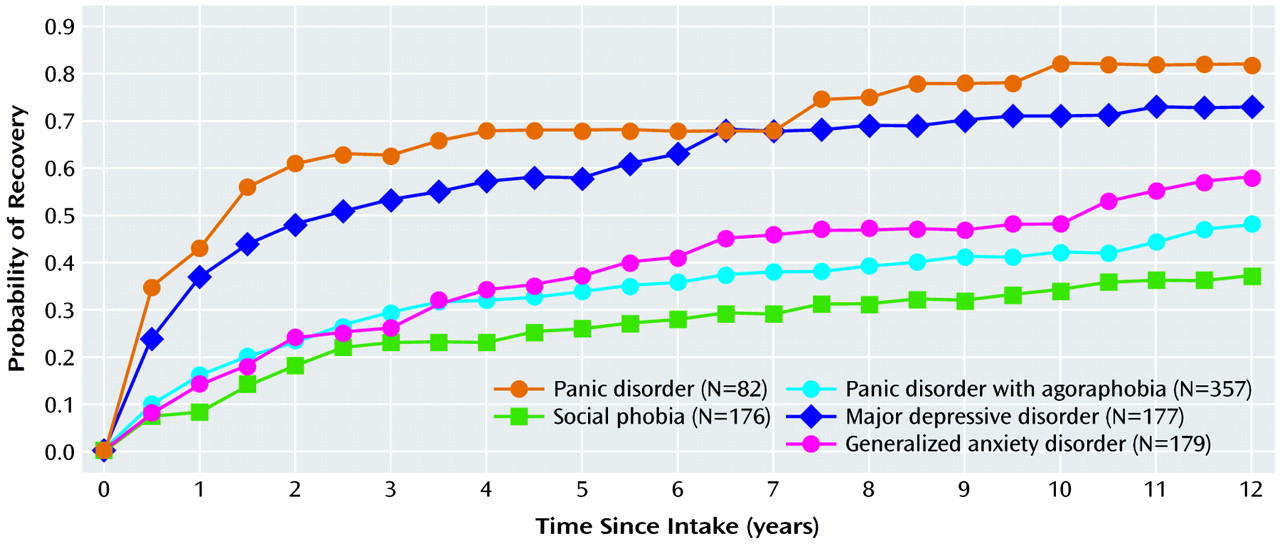

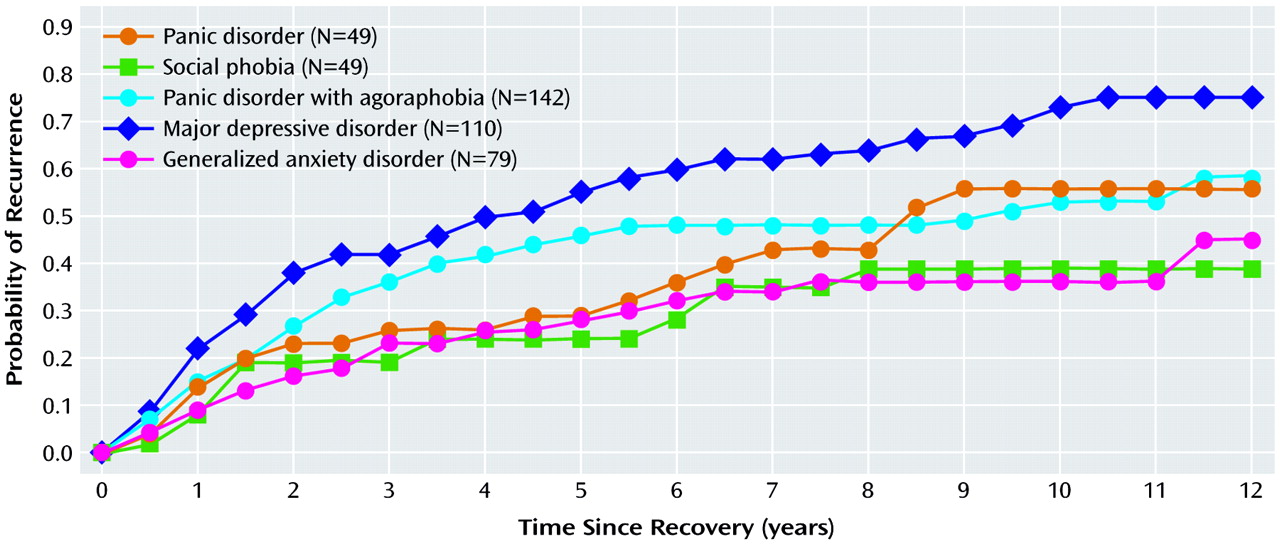

To our knowledge, this study is the first to present data from more than a decade of prospective follow-up of the clinical course of anxiety disorders. The data suggest that, with the exception of panic disorder without agoraphobia, the anxiety disorders examined in this study are insidious and are characterized by a chronic clinical course with low rates of recovery and relatively high probabilities of recurrence. Clinical course data on panic disorder without agoraphobia and panic disorder with agoraphobia indicated that although panic disorder without agoraphobia remits at a much faster rate than panic disorder with agoraphobia, the rates of recurrence for the two disorders over 12 years are nearly identical (0.56 and 0.58, respectively). Patients with panic disorder with agoraphobia had, on average, an earlier age at onset and a longer duration of their intake episode, compared with patients who had panic disorder without agoraphobia. This difference in recovery rates is consistent with findings of prior studies examining clinical course (

21–

24) and supports the hypothesis that the presence of agoraphobic avoidance unfavorably affects long-term outcome. Differences in clinical course also lend support to the premise that the presence of agoraphobia may be a severity factor for panic disorder. For example, Starcevic and colleagues (

25) found that patients with panic disorder with agoraphobia reported a greater number of panic symptoms and a more frequent occurrence of panic attacks than did patients with panic disorder without agoraphobia. They suggested that the severity of panic attacks, along with a variety of anticipatory fears about the consequences of the attacks, may contribute to the development of agoraphobia. In other studies, subjects with panic disorder with agoraphobia scored significantly higher on measures of perfectionism and anxious thoughts, compared with subjects with panic disorder without agoraphobia (

26,

27).

In our study, the patients with panic disorder without agoraphobia had higher recovery rates, spent considerably less time in illness episodes, and were less affected by comorbid conditions, compared with patients with any of the other anxiety disorders we considered. These findings lend support to the view that panic disorder without agoraphobia may be a distinct disorder that deserves more careful research scrutiny apart from panic disorder with agoraphobia.

Social phobia, the most common of the anxiety disorders, was found to be the most chronic; patients with social phobia had a 0.63 probability of remaining in the original intake episode even after 12 years of follow-up. However, patients who did recover from social phobia had a lower rate of recurrence (probability=0.39) over 12 years, compared with patients with panic disorder (with or without agoraphobia), generalized anxiety disorder, or major depressive disorder. These findings suggest that although social phobia is typically a chronic, unremitting disorder, patients with social phobia whose symptoms improve to the point of recovery tend to stay well, relative to patients with other anxiety disorders.

Other than the Harvard/Brown Anxiety Disorders Research Program, there exist very few studies examining the long-term clinical course of generalized anxiety disorder (

28–

30). A dozen years of follow-up in the project indicate that generalized anxiety disorder is a chronic anxiety disorder, with 42% of patients remaining in their intake episode after 12 years. Of those who did recover, nearly one-half subsequently had a recurrence. These results are clearly inconsistent with earlier assumptions, reflected in the DSM-III criteria, that generalized anxiety disorder is a residual and innocuous condition that usually does not lead to significant impairment. Rather, the long-term course appears to be chronic in nature, with more recent studies showing significant impairment across multiple domains (

31–

35).

Examination of the clinical course of comorbid depression in Harvard/Brown Anxiety Disorders Research Program patients indicates a relatively high recovery rate and substantial likelihood of recurrence. The recovery rate over 12 years was found to be substantially higher for major depressive disorder than for the anxiety disorders, except for panic disorder without agoraphobia. However, compared with the 0.93 rate of recovery from major depressive disorder for patients in the Collaborative Depression Study, a similar prospective study examining the course of mood disorders (

36), the 0.73 rate of recovery over 12 years in the Harvard/Brown Anxiety Disorders Research Program was much lower, suggesting that the presence of comorbid anxiety disorders reduces the overall likelihood of recovering from depression. Compared with survival estimates of recurrence of major depressive disorder from the Collaborative Depression Study (estimate of recurrence=0.80), the pattern of recurrence over 12 years for major depressive disorder patients in the Harvard/Brown Anxiety Disorders Research Program (who had major depressive disorder comorbid with anxiety disorders) appears to be very similar (rate of recurrence=0.75) (

Figure 2).

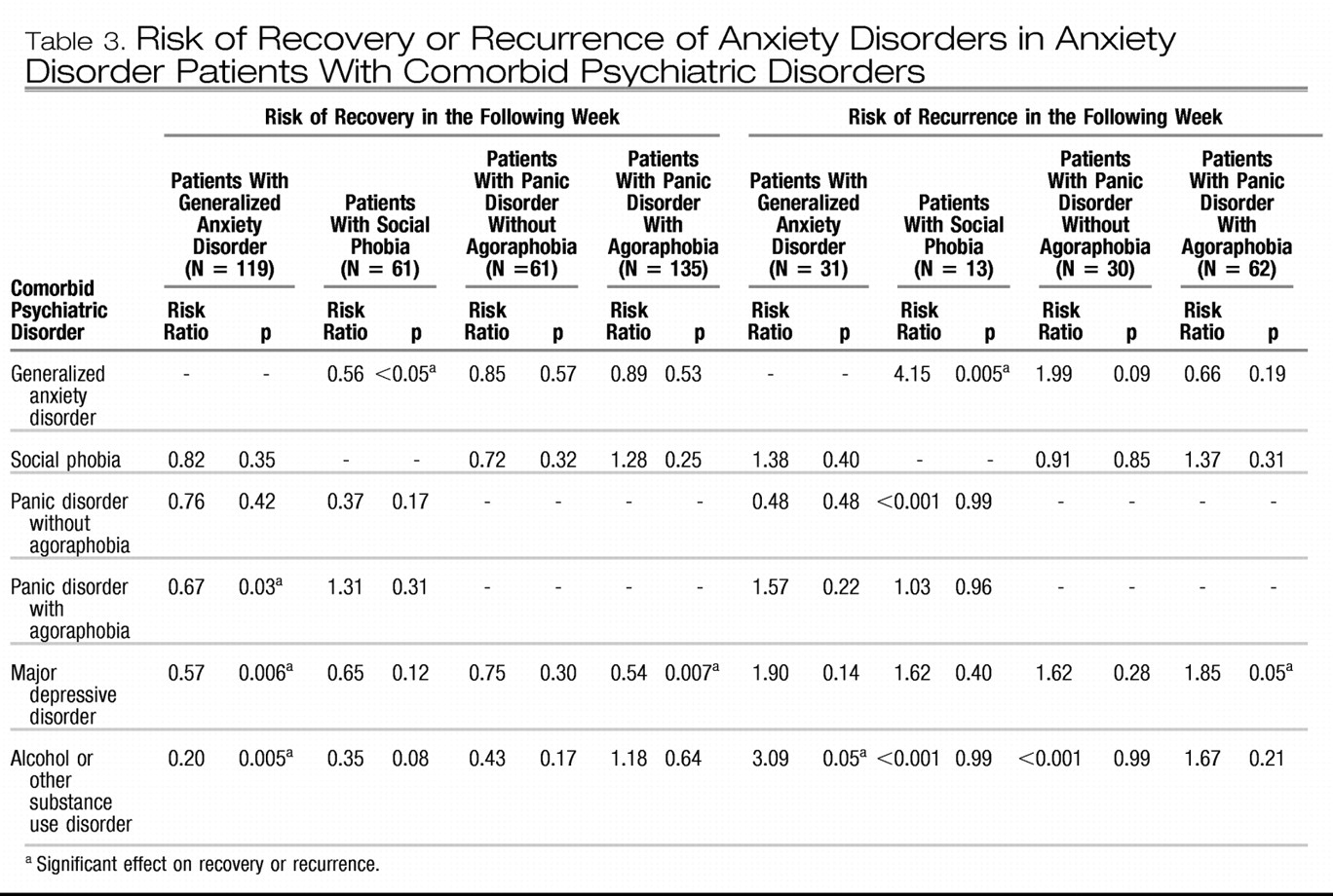

One of the strengths of this study is its examination of the differential effects of the various comorbid conditions on anxiety disorder course. Although previous studies indicated that comorbid axis I and II diagnoses complicate the course of generalized anxiety disorder, only a few have identified specific predictors of recovery and recurrence (

11,

37). Consistent with an earlier study in the Harvard/ Brown Anxiety Disorders Research Program (

38), the current study found a lower likelihood of recovery from generalized anxiety disorder in patients with comorbid major depressive disorder and in patients with comorbid panic disorder with agoraphobia. In addition, the presence of a comorbid alcohol or other substance use disorder significantly decreased the likelihood of recovery from generalized anxiety disorder and significantly increased the risk of recurrence of this disorder. These findings, combined with the findings of Compton and colleagues (

39), who reported that generalized anxiety disorder predicted the presence of additional substance dependence diagnoses, highlight the insidious reinforcing influence that generalized anxiety disorder and the alcohol and other substance use disorders have on each other.

One noteworthy predictor of clinical course was the influence of comorbid generalized anxiety disorder, which was associated with a significantly lower likelihood of recovery from social phobia and a higher likelihood of its subsequent recurrence. This finding is consistent with the finding of Mennin and colleagues (

40) that patients with social anxiety with comorbid generalized anxiety disorder demonstrated greater severity on measures of social anxiety, avoidance, functional impairment, and overall psychopathology, compared with patients without comorbid generalized anxiety disorder. Taken together, these previous findings and our current findings suggest that comorbid generalized anxiety disorder exacerbates the chronic course of social phobia, further impairing individuals with this disorder.

Patients with panic disorder with agoraphobia and comorbid depression were less likely to recover from their panic disorder and more likely to have a subsequent recurrence. This finding is consistent with findings of prior studies in which comorbid major depressive disorder negatively affected the outcome of panic disorder with agoraphobia (

22,

41,

42). Although comorbid major depressive disorder was not found to significantly affect the recurrence rates of generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, and panic disorder without agoraphobia, the risk ratios indicated that the presence of comorbid depression increased by 62%–90% the odds of the recurrence of generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, and panic disorder without agoraphobia. Thus, our lack of significant findings could have been due to the low number of recoveries observed for many of the anxiety disorders, thus reducing power to detect additional relationships.

The naturalistic design of this study can be viewed as both a strength and a limitation. Although it did not allow us to manipulate variables that might affect the course of anxiety disorders, it did provide a view of what is occurring in the real world in terms of the course of illness in clinical populations. This study is limited in its inclusion of clinical subjects only. Thus, results may not be generalizable to nonclinical populations. The subjects in our study may have been more severely impaired by their disorders than persons with disorders who do not seek treatment. In addition, because the subjects were recruited in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the results may not be indicative of patients who received a diagnosis more recently.

Although the treatment received by patients in the study was not found to be predictive of anxiety disorder course, the lack of a relationship was not unexpected and should be interpreted with caution. The Harvard/Brown Anxiety Disorders Research Program is an observational study of anxiety disorders, and, by design, the project observes but does not manipulate the treatment received by subjects. In naturalistic studies, adjustment for treatment effects is complex because of the well-known bias for patients with the most severe problems to receive the most treatment. Future studies in this project will employ newer statistical techniques (treatment propensity score analyses) that will help to minimize biases by matching treated and untreated subjects with regard to their estimated need for treatment.

A final limitation may exist in our definitions of recovery and recurrence. One of the major difficulties in comparing the course of anxiety disorders across studies is the lack of consensus definitions of recovery and recurrence. For example, recurrence of panic disorder is defined differently in almost all of the small number of studies of panic disorder course, which makes comparison of findings difficult. Shear and others (

43) noted that the characteristics of the clinical course of panic disorder are the primary reason for the difficulty of defining recurrence and stated that the mere presence or absence of panic attacks should not be the only factor in determining whether an individual has had a recurrence of panic disorder. Other factors such as level of phobic avoidance and persistence of the fear of future panic attacks should be carefully considered. During the consensus development conference on the treatment of panic disorder, a committee also noted the lack of consistency across researchers in defining how “responders” are characterized, as well as how recovery and recurrence are defined (

44). They recommended the establishment of procedures to ensure comparability of studies, stating that because the frequency of panic attacks is so variable, longer time frames for observation are preferable, with 1 month the optimal time to assess whether a patient with panic disorder is recovering or having a recurrence.

Our findings highlight the importance and need for longitudinal research to map the long-term clinical course of anxiety disorders. Moreover, examination of the potential negative influences of comorbid psychiatric diagnoses on overall clinical course can add a wealth of information to our understanding of the diagnosis and treatment of these disorders. These comorbid conditions should not be considered exclusion criteria for potential participants in future anxiety disorders research. On the contrary, inclusion of patients with comorbid conditions can provide clinicians and public policy makers with rich and much needed information about the effects of psychiatric comorbidity on the long-term outcome of anxiety disorders. Delineating the role that psychiatric comorbidity has on the course of anxiety disorders will help to facilitate the refinement of existing treatments, which should improve outcomes.