METHODS

A MEDLINE search of articles published in English from 1966 to 2006 was conducted, using the following search terms: randomized clinical trial, somatoform disorders, somatization disorder, undifferentiated somatoform disorder, hypochrondriasis, conversion disorder, pain disorder, and body dysmorphic disorder.

Potential studies were also identified from bibliographies of retrieved articles, as well as several recent reviews of selected treatments (

12,

14,

16,

17). Prepost studies (i.e., where outcomes were assessed in a single group of patients before and after an intervention) were excluded. Also excluded were studies that focused on specific symptoms (e.g., back pain, headache) or functional somatic syndromes (e.g., irritable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia).

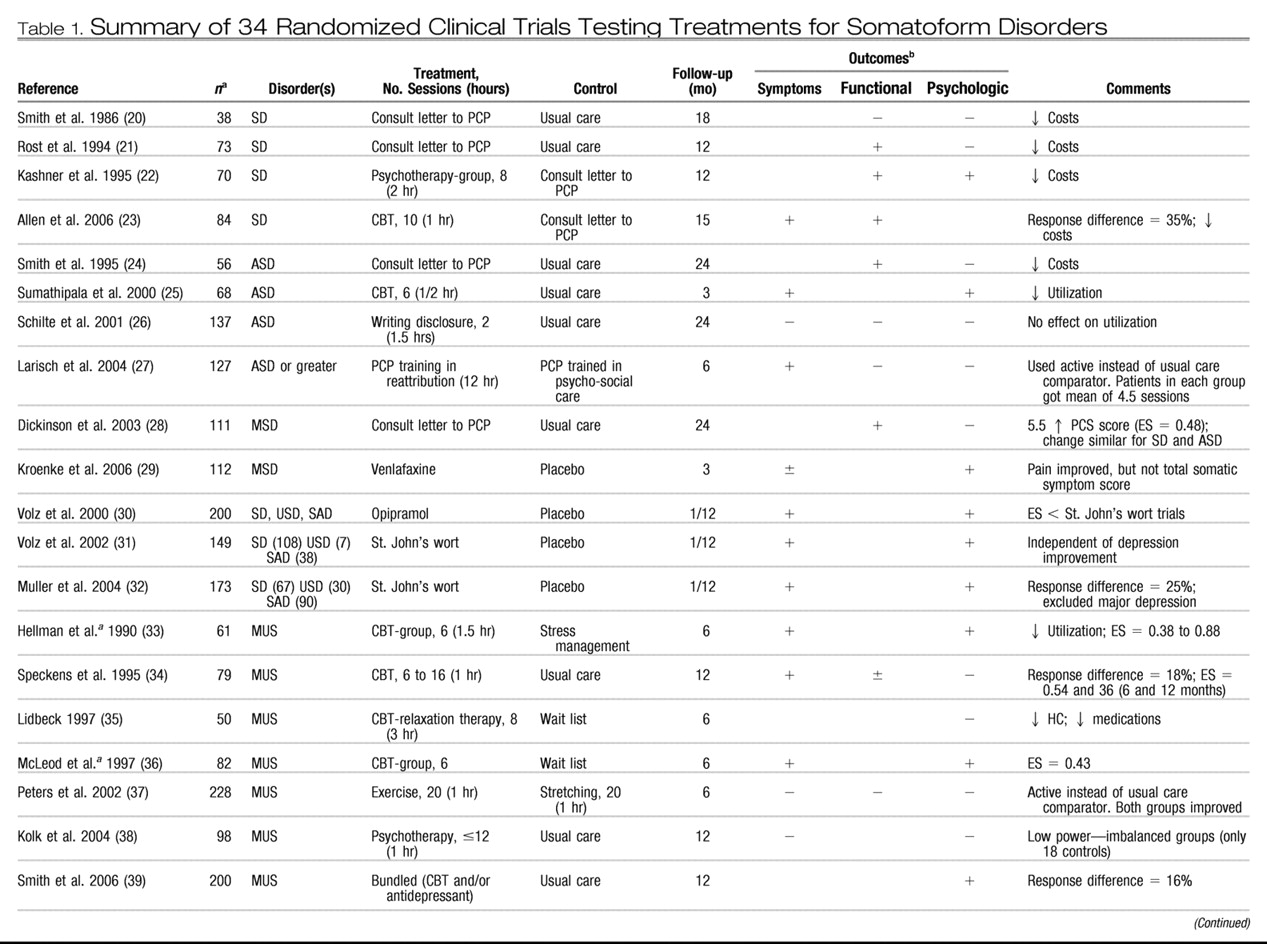

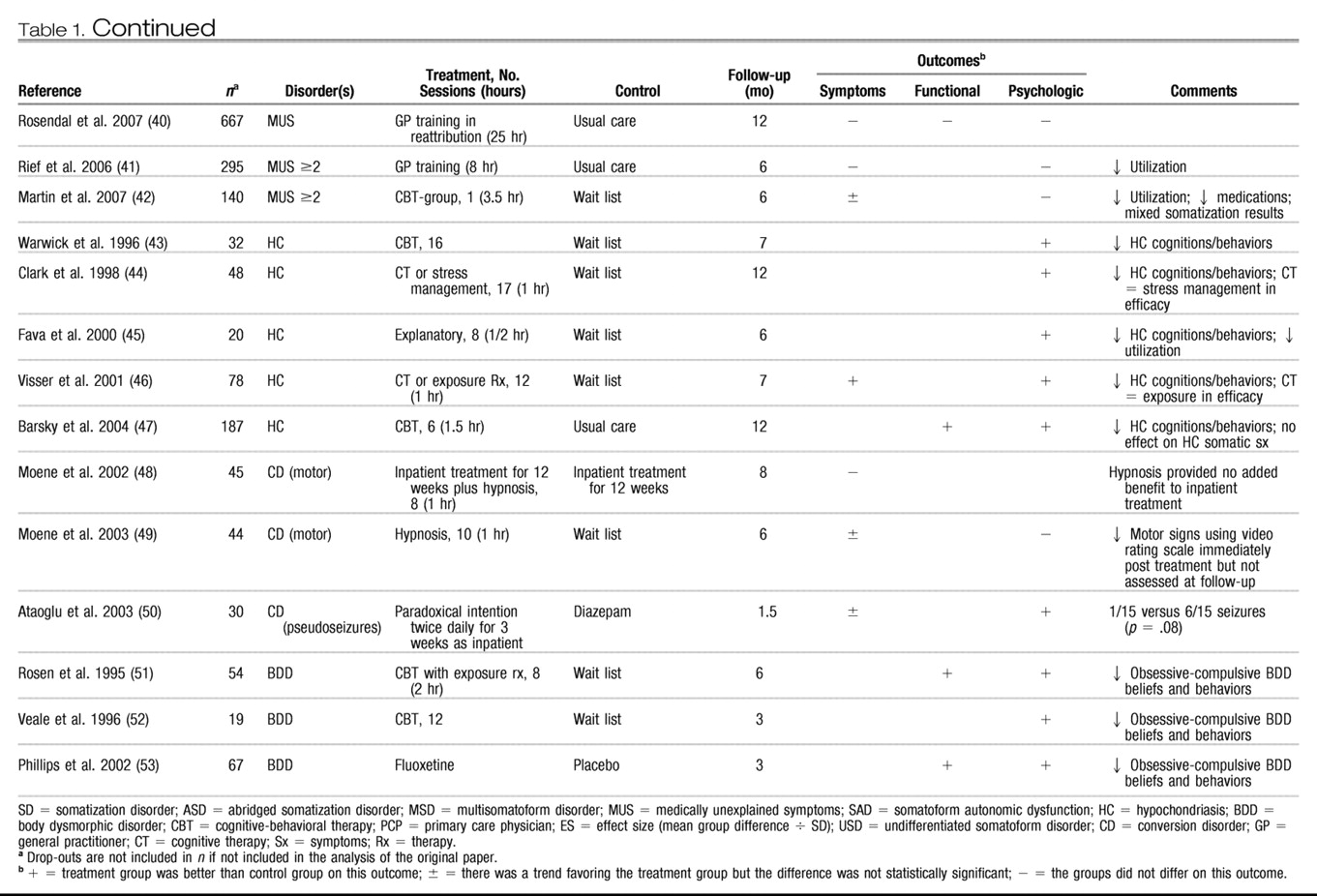

Data were abstracted on the following key variables: somatoform disorder category, sample size, type of intervention, number of and duration of sessions, type of control group, duration of follow-up, outcomes evaluated, and treatment effect. The following types of patient-centered outcomes were evaluated: a) symptoms (i.e., the study's main measure of somatic symptom count and/or severity); b) functional status (i.e., the study's main measure of functional impairment or quality of life); and c) psychological (i.e., either a domain specific to the disorder, such as hypochondriacal or body dysmorphic beliefs and behaviors, or a generic measure of depression, anxiety, or psychological distress). For each trial, these three outcomes were assessed as positive (outcome was better in the treatment group than the control group), equivocal (there was a trend favoring the treatment group but the group difference was not statistically significant), negative (the groups did not differ), or not assessed. Secondary variables for which data were abstracted include patient demographics (age, gender, educational level, race), and country as well as type of clinic in which the study was conducted.

A standard meta-analytic approach to aggregate the reported data on efficacy was not possible because of the small number of trials for a given intervention within broad treatment classes; substantial differences in the definition and types of reported outcomes; and considerable variation in the reporting of statistical details, such as exact

p values and standard deviations. Moreover, many studies neither stated what the primary outcome was nor prespecified the sample size needed to adequately test for a primary outcome. Therefore, similar to several previous literature syntheses of mental health interventions across multiple conditions (

12,

18), a vote-counting approach (

19) was used to classify each trial as positive or negative. Any trial that reported statistically significant improvement in at least one of the three patient-centered outcomes was operationally defined as a positive trial.

DISCUSSION

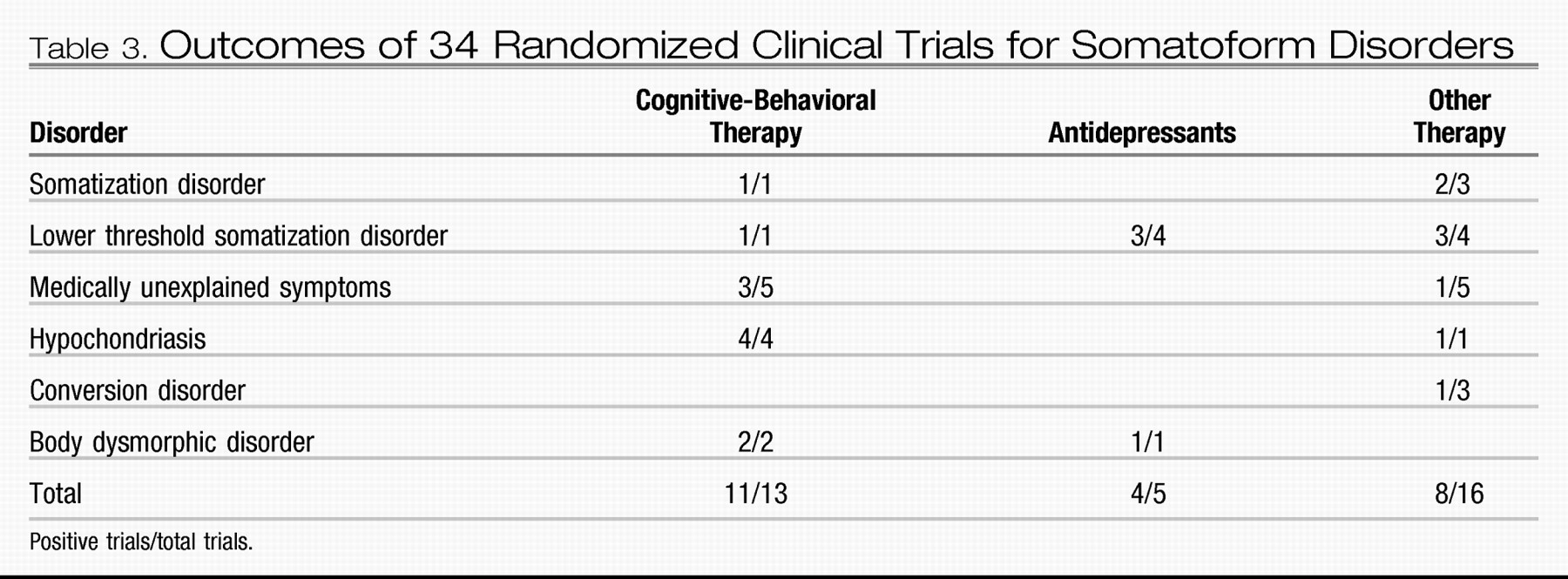

This literature synthesis allows one strong and several tentative conclusions regarding the efficacy of treatment for somatoform disorders. First, CBT is consistently effective (11 of 13 trials) across a spectrum of somatoform disorders including SD and its lower threshold variants, hypochondriasis and BDD. Second, a psychiatric consultation letter to the primary care physician about strategies for managing the somatizing patient seems to improve physical functioning (three of four trials) and reduce costs, although surprisingly the effect on somatic symptoms themselves has not been reported. Third, although there is preliminary evidence that antidepressants may be beneficial, the degree to which this is a general effect mediated through reduced depression and anxiety versus a specific effect on somatic symptoms needs to be better ascertained. A variety of other treatments have been evaluated for which the results have been either negative or inconclusive.

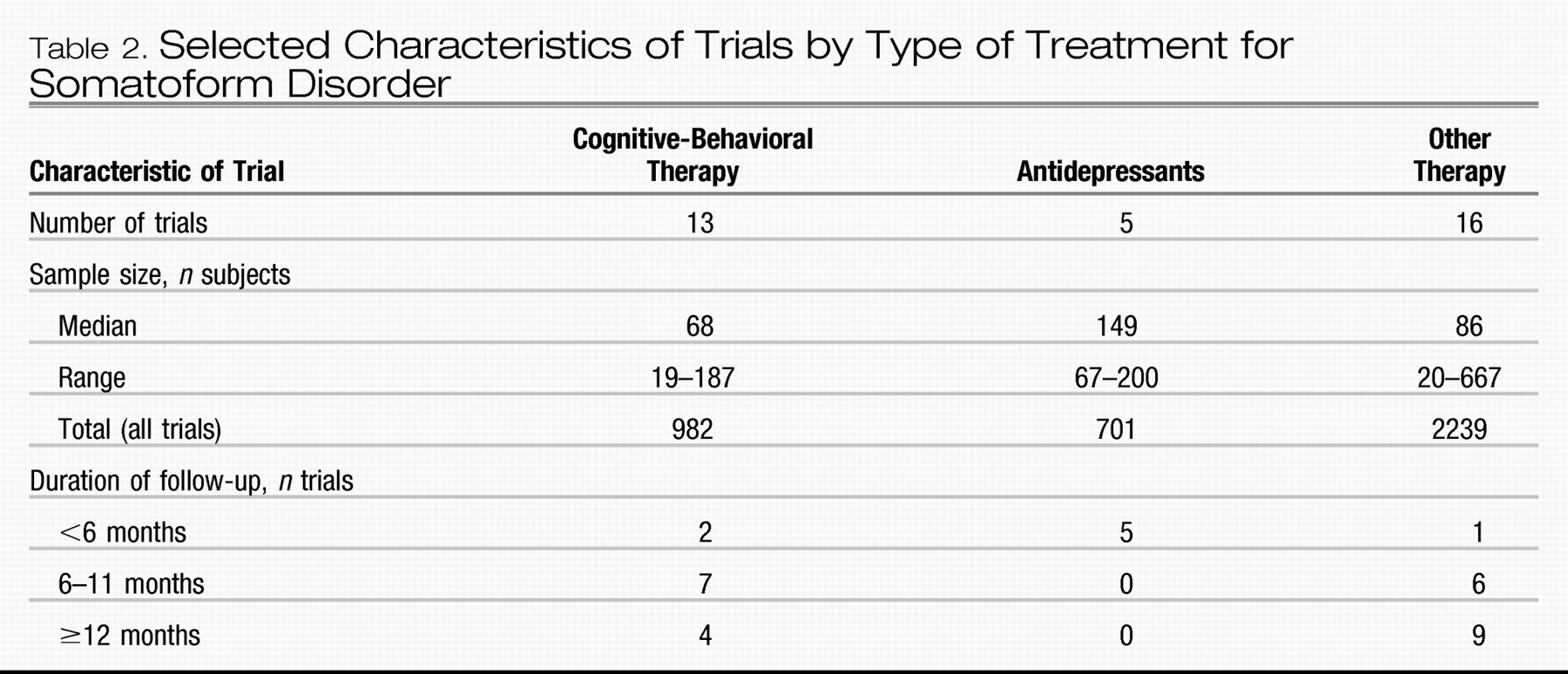

All trials except three were published in the past decade. This could be due to a number of factors ranging from substantial changes in classification, a paucity of interest in somatoform disorders, lack of clinical trial funding for these disorders, and the fact that most somatizing patients present in primary care and fewer are referred to mental health specialists than patients with other mental disorders. Although somatoform disorders are just as common as depression and anxiety in primary care, the number and quality of trials to inform our treatment of somatoform disorders are far less.

The literature reviewed has important limitations, which in turn weaken the conclusions we can draw, except for the likely efficacy of CBT. First, the heterogeneity of conditions, disease definitions, treatments, intervention type and intensity, outcomes, and duration of follow-up precluded quantitative pooling of study data. Thus, we had to resort to a crude vote-counting approach of characterizing studies as positive or negative, and a narrative synthesis rather than a formal meta-analysis. Second, most trials measured multiple outcomes and reported neither which outcome was primary nor a prespecified sample size. Therefore, our operational definition of a positive trial as needing to show benefit for only one of the three patient-centered outcomes could overestimate treatment benefits because multiple outcomes were often assessed and analyses were not typically adjusted for multiple hypothesis testing. On the other hand, many studies had small sample sizes meaning the differences that were found had to be of at least a moderate magnitude to be statistically significant. Third, the comparison arm for most studies was a usual care, wait list, or active comparator rather than placebo control. Consequently, blinding of the patient was impossible in many of these studies, and blinding of the outcome assessment was often not specified.

Functional somatic syndromes (e.g., irritable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome) and individual chronic symptoms (e.g., headache, low back pain) were not the subject of this review but exhibit considerable overlap with somatoform disorders (

54) as well as depression and anxiety (

55). It is therefore notable that evidence-based reviews have established the efficacy of both CBT and antidepressants for these somatic conditions (

11–

15,

56). Additionally, it seems the effect of CBT and antidepressants on somatic symptoms is not entirely mediated through reduction of depression and psychological distress (

11,

12). On the other hand, depression and anxiety frequently co-occur in patients with functional somatic syndromes as well as somatoform disorders (

4,

57), and some studies have suggested that somatic symptoms may improve to a lesser degree than emotional symptoms (

58,

59).

Regarding type of treatment, the strongest and most consistent evidence exists for CBT. In contrast, the number of antidepressant trials was small. Of these five trials, four were positive for the prespecified primary outcome, whereas the other was positive for one of the other patient-centered out-comes considered primary for this review. Compared with the nonpharmacological treatment studies, antidepressants had on average larger patient samples, had a prespecified primary outcome, and were placebo-controlled; the latter two factors would tend to increase the likelihood of a negative trial. On the other hand, antidepressant trials tended to have shorter follow-up periods, leaving unanswered questions about the persistence of benefits and the need for chronic therapy. Also, the three antidepressant trials, which showed benefits for SD-spectrum disorders, were all conducted in Germany and used either St. John's wort or opipramolol rather than antidepressants typically prescribed in the US. Much stronger evidence is needed regarding the efficacy of pharmacotherapy, including the magnitude and sustainability of its benefits for somatic symptoms as well as its independent effect not mediated by improvement of comorbid depression and anxiety.

Ironically, a psychiatric consultation letter provided to PCPs was effective in three of four trials, but specialized PCP training was effective in only one of three trials. Although substantial differences between trials make comparisons difficult, several points should be mentioned. First, although the consultation letter trials showed modest improvement in physical functioning, none of the trials reported on somatic symptom outcomes, which is notable in that all four trials were performed in SD or its lower threshold variants. Second, the consultation letter trials were all performed by the same group and had small sample sizes. Nonetheless, the fact that PCP training trials have not shown a convincing effect means further work is needed to determine the optimal balance between PCP care, collaborative care, or referral for CBT for improving outcomes of somatoform disorders in primary care.

In terms of type of somatoform disorder, the most evidence (23 of the 34 trials) (

Table 3) exists for the family of related disorders including SD, its abridged or subthreshold variants, and medically unexplained symptoms. Clinical trial evidence for the treatment for other somatoform disorders ranges from modest to limited. The evidence supporting CBT in hypochondriasis is consistent across four trials. Two trials of CBT and one trial of fluoxetine were beneficial in BDD. A meta-analysis of treatments for BDD (

60) included, in addition to the RCTs reported here, three case series and one crossover trial of antidepressants (three with SSRI, one with clomipramine) involving 89 patients, and eight case series of psychological treatments (four with behavioral therapy, three with CBT, and one with cognitive therapy) involving 85 patients. Including all studies where the effect size could be derived from the published date, the mean effect sizes were 0.92 for antidepressants (five studies), 1.43 for behavioral therapy (four studies), and 1.78 for CBT (five studies). Effect sizes of 0.8 or greater are considered large therapeutic effects (

61). Finally, the three small trials in conversion disorder were inconclusive, yet they are the only trials that qualified for inclusion in a recent Cochrane Collaboration review (

62). Although we found no trials focusing on DSM-IV Pain Disorder or Undifferentiated Pain Disorder per se, previous evidence-based reviews of antidepressants, CBT, and other psychological treatments for functional symptoms had patient samples where pain was often a cardinal symptom (

11–

15,

56). Also, many of the trials in our review that focused on patients with lower-threshold SD and/or medically unexplained symptoms likely included many patients with pain symptoms or undifferentiated SD.

Despite the evidence for some potentially effective treatments, many clinicians find somatoform disorders and medically unexplained symptoms among the most difficult conditions to treat, both in terms of outcomes as well as clinician-patient interactions (

10,

63). The reasons for this may be multifactorial including lack of clinician knowledge about evidence-based treatments, lack of access to or inadequate reimbursement for CBT and other psychotherapeutic interventions, concomitant personality disorders, and limited time in busy outpatient encounters with other competing demands. Also, there may be selection bias in published trials. For example, despite the consistent evidence supporting CBT, many such patients seen in clinical practice may refuse referral to mental health providers. Those with somatoform disorders who are convinced their problems are “physical” may be less likely to enroll in studies of “psychological” treatments.

In summary, there is strong evidence supporting the efficacy of CBT across several types of somatoform disorders, and moderate evidence supporting a psychiatric consultation letter in SD and its lower threshold variants. Antidepressants also seem promising, particularly for functional somatic syndromes, but require further study in somatoform disorders per se. The most prevalent type of somatoform disorder is the family of conditions that includes SD, its lower threshold variants including medically unexplained symptoms, USD, and pain disorder. The overlap along a continuum of these disorders with one another and with functional somatic syndromes has important implications for revised classification in DSM-V as well as common treatments (

54,

64). Also, psychotherapeutic interventions other than CBT (e.g., interpersonal therapy, problem-solving therapy, brief psychodynamic therapy) as well as treatments outside of what are traditionally considered “psychological” (e.g., optimizing analgesics, the use of pain self-management programs) merit further study for somatoform disorders. Finally, most trials have studied single treatments, whereas it is likely that combining treatments may be necessary in patients with chronic somatic conditions. Because somatoform disorders are as prevalent as depression and anxiety in primary care and account for considerable disability and costs, enhancing treatment outcomes for this often-neglected category of mental disorders should be a priority.