The three major classification systems used by clinicians and researchers for insomnia are the DSM-IV-TR, the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 2nd edition (ICSD-2) and the ICD-10.

The DSM-IV-TR organizes sleep disorders into four major sections according to presumed etiology (primary, related to another mental disorder, due to a general medical condition, and substance-induced). According to the DSM-IV-TR, the essential feature of primary insomnia is difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep or of nonrestorative sleep (i.e., sleep that is restless, light, or of poor quality), which lasts for at least 1 month and causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

The ICSD-2, which was developed by sleep specialists, organizes diagnoses according to the presumed pathophysiology underlying the sleep disturbance, including 11 diagnoses related to insomnia. The ICD-10 criteria differ from those of the DSM-IV-TR and ICSD-2 in that they include, for insomnia, specific frequency criteria, i.e., the sleep disturbance must occur at least 3 nights a week. The systems also differ in terms of requirements for symptom severity (DSM-IV-TR specifies that symptoms must cause significant distress or impairment) and duration (DSM-IV-TR specifies at least 4 weeks).

From a clinical standpoint, insomnia can be classified into the following categories.

Comorbid insomnia

This category includes insomnia disorders that are comorbid with other medical and psychiatric conditions and other sleep disorders. It represents the vast majority of insomnia. Historically, this has also been referred to as “secondary insomnia.” However, a recent National Institutes of Health State of the Science Conference statement recommended the use of term “comorbid insomnia,” noting that the limited understanding of mechanistic pathways in insomnia precludes drawing firm conclusions about the nature of the associations between insomnia and comorbid conditions or the direction of causality.

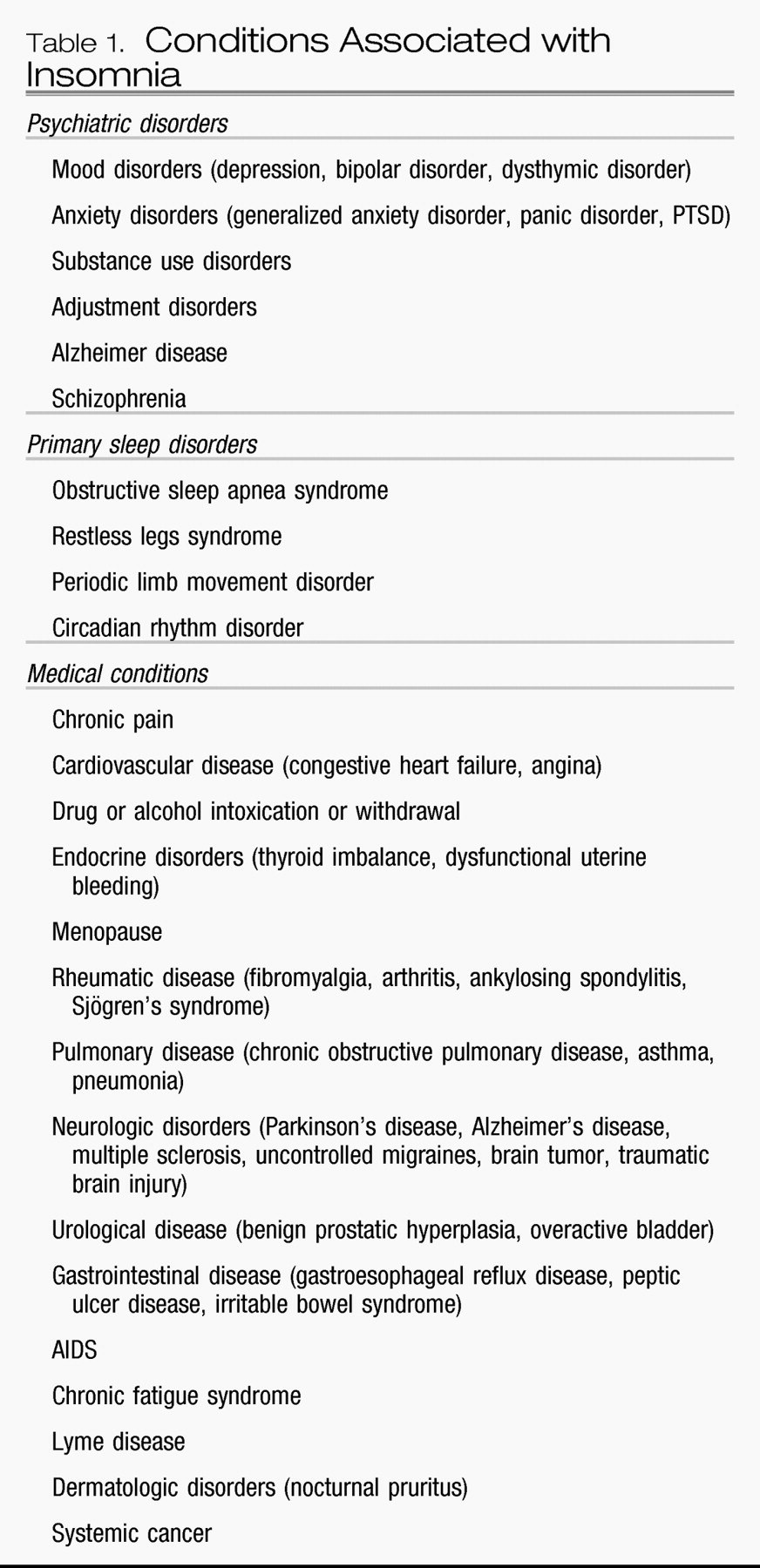

Insomnia can be associated with a host of medical, psychiatric, and sleep disorders. Some of these are listed in

Table 1 (

52).

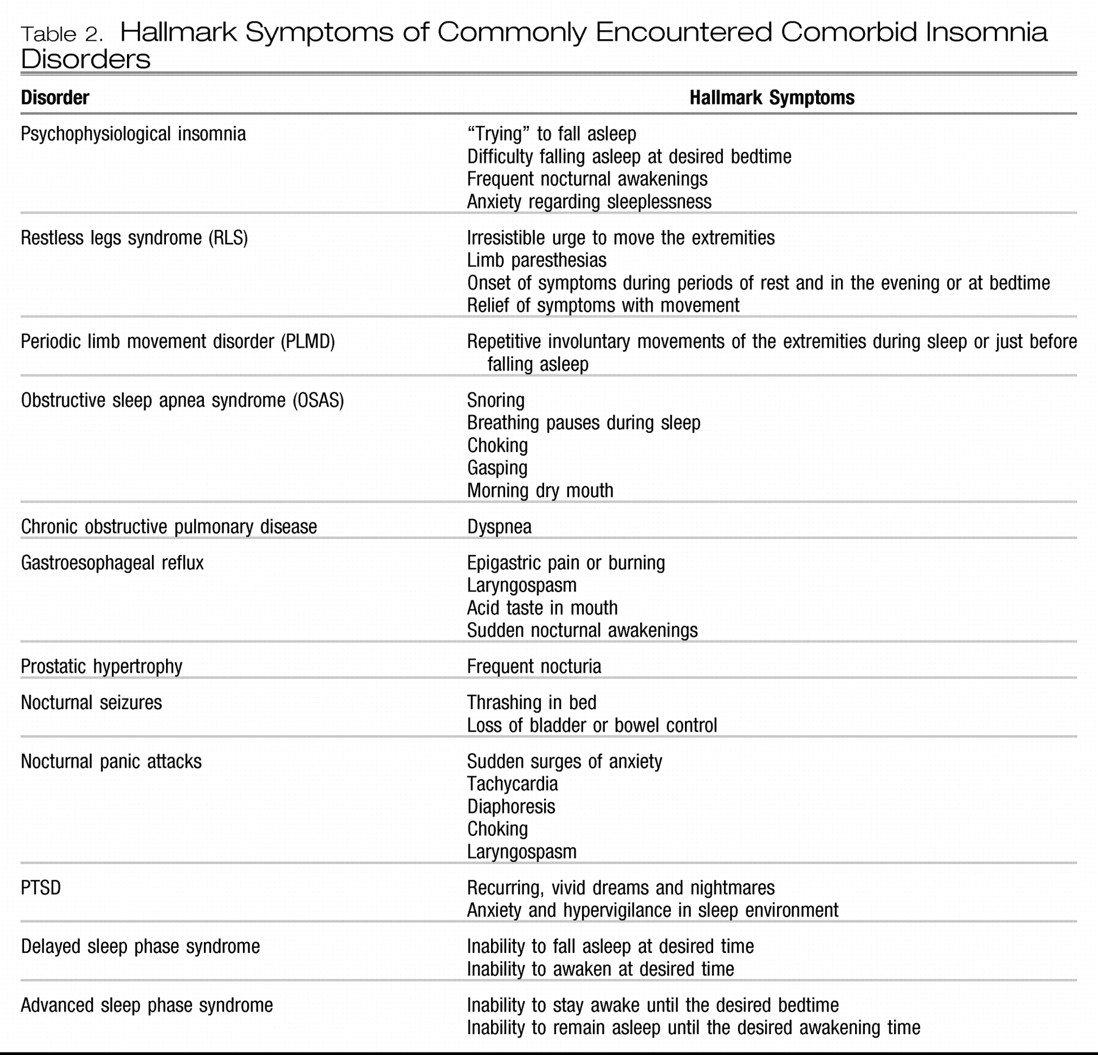

Table 2 lists some of the commonly encountered comorbid insomnia disorders and their defining symptoms (

53). A variety of medications can also cause the complaint of insomnia, including anticholinergic agents, antihypertensives, antineoplastics, CNS stimulants, hormones, antidepressants, and antipsychotics as well as withdrawal from sedating agents (

52). Anxiety and mood disorders represent some of the most commonly encountered disorders in psychiatric practice and are highly associated with insomnia.

Mood disorders

There is a strong association between insomnia and mood disorders. The complaint of insomnia is voiced by most patients with major depression. Sleep patterns include difficulty falling asleep, frequent nocturnal awakenings, early morning awakening, nonrestorative sleep, decreased total sleep, and disturbing dreams. Daytime fatigue is also common (

54). Insomnia is also a common complaint in bipolar patients in the depressed phase, yet hypersomnia is also a frequent complaint, with extended nocturnal sleep periods, difficulty awakening, and excessive daytime sleepiness (

55). Hypersomnia is also common in seasonal affective disorder during episodes of winter depression. During manic periods, however, patients usually report significantly reduced amounts of total sleep, often with a subjective sense of a decreased need for sleep.

Conversely, 14%–20% of individuals with significant complaints of insomnia show evidence of major depression, whereas rates of depression are less than 1% in those without sleep complaints (

8,

56). Although clinical wisdom suggests that insomnia is a consequence of mood disorders, longitudinal studies indicate that insomnia is more likely to emerge before rather than after the onset of the acute phase of a mood disorder (

57). Indeed, the complaint of insomnia also confers an increased risk for the development of new psychiatric disorders over the course of the ensuing year, a risk that diminishes if the insomnia resolves (

56). Other studies have noted an enhanced risk for mood disorders for a median of 34 years after the complaint of insomnia (

57). Thus, insomnia in early adulthood was associated with an increased risk of depression some 17–30 years later. Other studies have shown that the occurrence and persistence of insomnia confers an enhanced risk for the future occurrence of anxiety and substance use disorders (

36,

59). From a clinical standpoint, these data suggest that the presence of chronic insomnia should alert the clinician to the possibility of the future emergence of a mood, anxiety, or substance use disorder. In addition, the lack of sufficient response to the treatment of presumed primary insomnia should alert the clinician to the possibility of an underlying, disguised, mood, substance use, or anxiety disorder that may warrant independent management.

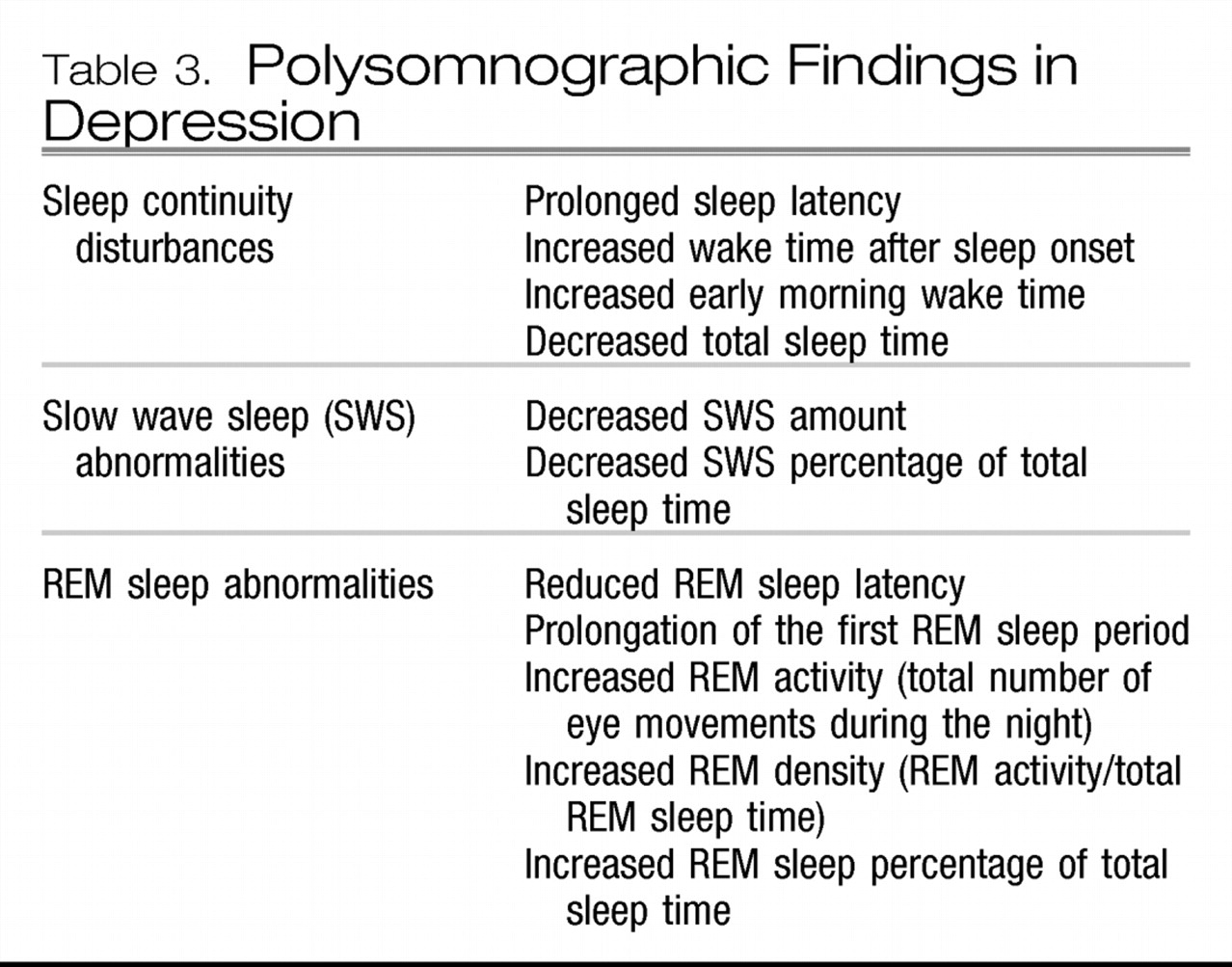

Polysomnographic studies have revealed a constellation of findings during major depressive episodes (

54,

59). These are listed in

Table 3.

The clinical relevance of these findings is not straightforward. They have, however, been used historically in research settings to establish a diagnosis of depression during the acute phase of a depressive episode, to identify individuals in the population who may be vulnerable for the future development of depression, to predict relapse, and to predict response to treatment. They have also been used to support various neurophysiological formulations regarding the pathophysiology of depression (

61).

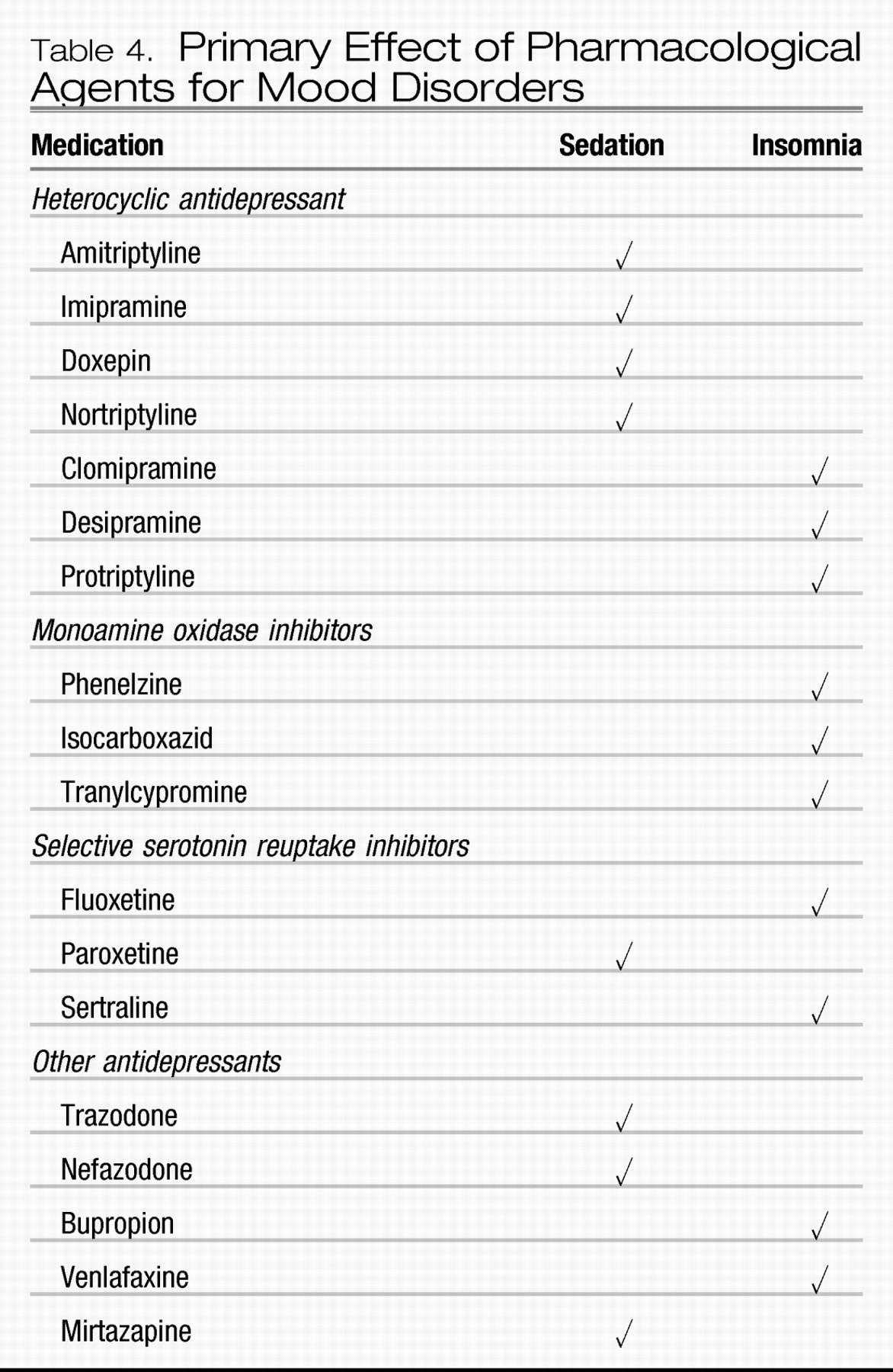

The treatment of disturbed sleep in mood disorders should start with the management of the underlying mood disorder. The short-term subjective effects of some of the more commonly used pharmacological agents are listed in

Table 4 (

61). It should be noted that antidepressant medications are not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of insomnia.

Nonpharmacological treatments directed primarily at the mood disorder can also diminish sleep disturbances, yet their effects may be more modest than those of antidepressants. Clinical wisdom suggests that effective management of the underlying mood disorder should provide relief from related sleep disturbances. However, pharmacological treatment studies indicate that less than 20% of full responders to antidepressant treatment are free of all major depressive disorder symptoms (

62) and nearly half of responders have persistent sleep disturbances. Therefore, it is often necessary to supplement antidepressants with sleep-specific treatments such as hypnotic medications and insomnia-specific cognitive behavior therapy, described in greater detail below.

Anxiety disorders

Insomnia and anxiety are closely related in a variety of ways. These symptoms coexist frequently in the clinical practice of medicine and may even involve common etiologies. Both can be symptomatic manifestations of other comorbid conditions. In addition, both can represent distinct primary conditions or syndromes in their own right. Anxiety disorders represent the most frequent psychiatric disorder in individuals with insomnia (

16). As noted above, insomnia often precedes the onset of an anxiety disorder. However, unlike the situation in mood disorders, insomnia is more likely to emerge at the same time (>38%) or after (>34%) the onset of the anxiety disorder (

57).

The comorbidity of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and insomnia is more frequent than that for all other anxiety disorders (

63). Objective studies in GAD reveal a longer sleep latency and an increase in the frequency of awakenings compared with those in control subjects. However, unlike in patients with major depression, patients with GAD appear to have normal REM latency (

64).

Insomnia is one of the core symptoms of PTSD and is thought to be a reflection of increased psychological and physiologic arousal (DSM-IV-TR) associated with the original experience of the traumatic event or its reexperiencing. Another core symptom of PTSD is distressing dreams and nightmares, reflections of the reexperiencing of the traumatic event. As with insomnia, their presence early in the aftermath of trauma is a strong predictor of the later development of PTSD itself (

65,

66). Nightmares may incorporate elements of or the entirety of the actual traumatic event and its affective correlates. However, the latent content of the dream (i.e., the traumatic event and its psychic correlates) may be disguised so that dreams may be affectively charged yet lack the factual recollection of the actual event or may not be remembered at all. Evidence is emerging to suggest that in the aftermath of trauma, the latter experience carries a more positive prognosis. Mellman et al. (

67) reported that within 6 weeks of traumatic events reports of dreams rated as “highly similar” to the traumatic experience and as distressing were associated with concurrent and subsequent PTSD severity. On the other hand, lack of dream recall or dreams that did not depict actual memories of the traumatic event were more characteristic of the group of individuals exposed to trauma who did not subsequently develop PTSD, although their dreams did contain some threatening scenarios. The authors theorized that dreams with highly replicative content represent a failure of adaptive emotional memory processing that is a normal function of REM sleep and dreaming.

Polysomnographic studies in PTSD have not revealed consistent findings in sleep initiation and maintenance, possibly because of the diversity in the nature of the populations examined and in the temporal relationship between the development of PTSD symptoms and the traumatic event itself. Some studies have shown an enhancement of phasic activity and eye movement density during REM sleep in those with PTSD as well as reports of nightmares and awakenings from REM sleep even early in the development of the disorder (

68).

Insomnia is not one of the diagnostic symptoms of panic disorder. However, insomnia, characterized by both impaired sleep initiation and maintenance, is more commonly reported in those with panic disorder than in normal individuals (

69). Insomnia can be related to episodes of panic, which can arise during sleep and result in the complaint of insomnia. The first awareness of panic in most people with this disorder is a somatic symptom such as racing heart or shortness of breath (

70), which results in sudden awakening with a feeling of physical intensity. Taylor et al. (

71) found that major spontaneous panic attacks clustered during the sleep period between 1:30 and 3:30 a.m. Contrary to popular belief, they generally do not occur in REM sleep. They have been observed to occur in slow-wave sleep and during the transition from stage 2 to slow-wave sleep (

66). Dreams are not commonly reported preceding panic episodes. Not all patients with panic disorder experience panic episodes during sleep.

Insomnia can also arise from recurrent sleep panic attacks, which, in turn, can create a state of anticipatory anxiety and apprehension over the prospect of yet another night of sleeplessness followed by another day of fatigue. A vicious cycle can then ensue in which excessive focus on sleep and trying to sleep causes greater tension and even greater impairment in sleep initiation and maintenance, thereby resulting in a second comorbid condition, i.e., psychophysiologic insomnia (see above).

Nonpharmacologic treatments for anxiety disorders include cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) and exposure therapy alone, in combination, or combined with relaxation training. These therapies share some similarities with the nonpharmacologic treatments for insomnia, described in greater detail below. Preliminary studies indicate that when used for the management of anxiety disorders, these therapies can also ameliorate insomnia. GAD-specific CBT can ameliorate insomnia when used for the treatment of GAD (

72), and imagery rehearsal for the nightmares of patients with PTSD can improve sleep, presumably as a secondary consequence of diminished nightmares (

73).

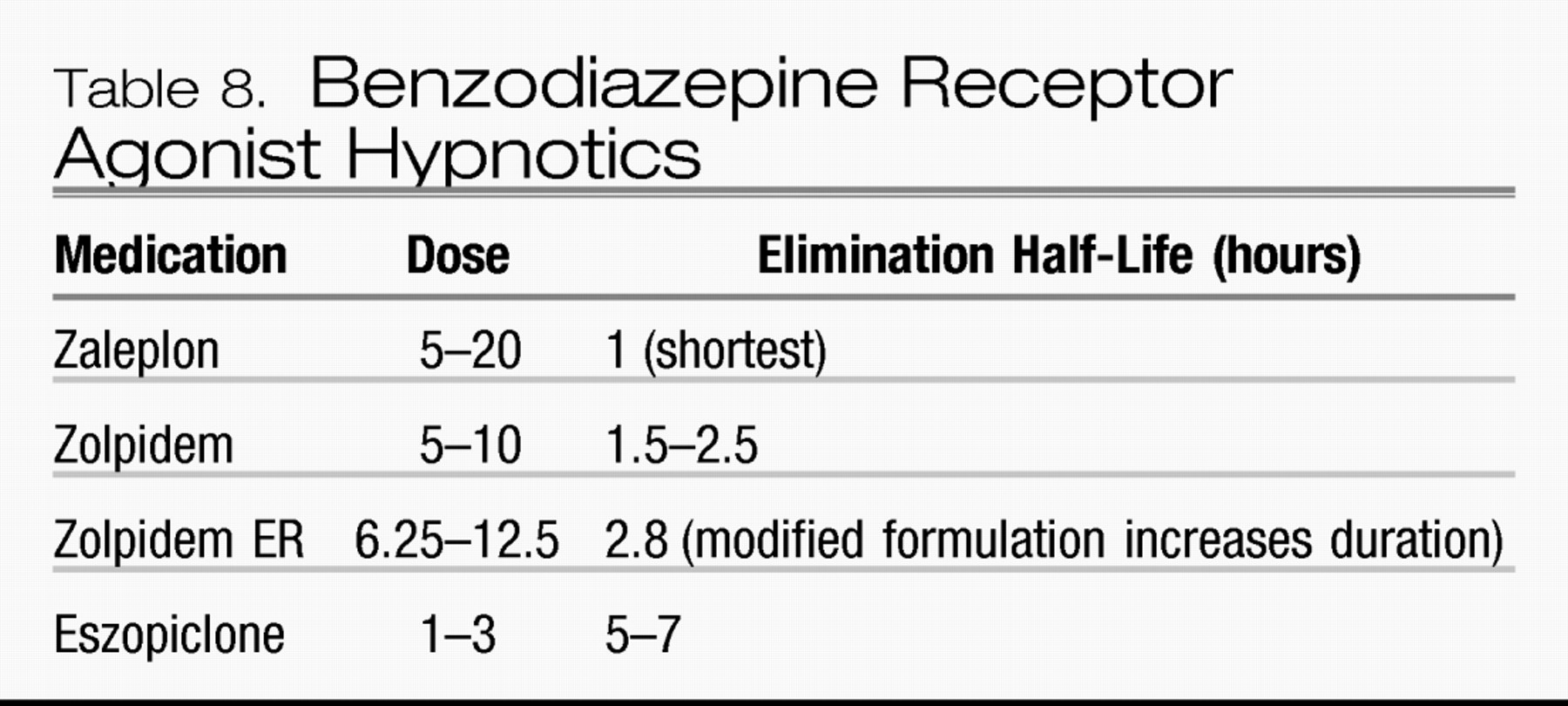

The benzodiazepine receptor agonists (GABAA receptor agonists) are effective for both anxiety and insomnia symptoms in patients with comorbid insomnia and anxiety disorders, although individual agents may not have an FDA-approved indication for both conditions. Antidepressants can also ameliorate insomnia in various anxiety disorders, as noted above, and, if insomnia persists after the management of the underlying anxiety disorder, the addition of hypnotic agents can be helpful.