INTRODUCTION

A number of studies have found that the risk of an overweight child or adolescent becoming an obese adult rises with both age and degree of obesity (

1–

6). In addition to its immediate negative effects on health, overweight in youth also increases the long-term risk of adult morbidity and mortality (

7), independent of adult obesity (

8,

9). Furthermore, overweight youth suffer from more social stigmatization and isolation (

10) and are at increased risk for psychological problems, such as greater depressive symptoms and anxiety, compared with their non-overweight peers (

11–

14).

Binge eating, marked by an individual ingesting large amounts of food while experiencing loss of control (LOC) over eating (

15), is the most commonly identified abnormal eating behavior among obese adults. Binge eating disorder (BED), a putative eating disorder in the DSM-IV-TR (

15), is characterized by recurrent episodes of binge eating accompanied by dysfunctional eating attitudes and marked distress (

15). Adults with BED suffer from higher levels of physical disabilities, poorer physical health, lower quality of life (

16,

17), and more psychiatric disturbance (

18–

20) than obese adults without an eating disorder, in addition to having disordered eating psychopathology at levels similar to those with bulimia nervosa (

18,

21). Moreover, BED has been associated with social impairment and poor interpersonal functioning (

17,

22–

24). Because individuals with BED do not regularly engage in inappropriate compensatory behaviors, BED and recurrent binge eating is often associated with excess body weight and obesity (

19,

25). Repeated binge eating has also been shown to predict the development of inappropriate weight gain and obesity in a community sample of adults (

26). Finally, some (

27–

29), but not all (

30–

32) studies have shown that persons with BED have poorer response to obesity treatment or more rapid regain of lost weight after treatment than those without an eating disorder.

The incidence of full-syndrome BED seems to be quite low in children. However, prevalence estimates should be considered with caution because developmentally appropriate techniques to measure binge eating among children have not yet been fully established. LOC eating episodes, which may consist of an objectively or subjectively large amount of food and occur with less frequency than required by the full DSM-IV-TR BED criteria (

15), seem to be more common in overweight youth than their non-overweight peers (

13,

33). Moreover, studies of non-treatment-seeking children have found that the experience of LOC during eating, regardless of the amount of food ingested, seems to be more salient in describing pathologic eating in children than classic binge episodes that require the consumption of a large amount of food (

13,

33–

35). This may, in part, be caused by difficulty in distinguishing what constitutes a “large amount of food” among growing children with varying nutritional needs (

36). Furthermore, rigorous interview methods used to assess aberrant eating patterns require conservative coding of an eating episode size (e.g., if an amount is ambiguously large, it is considered “not large”), often minimizing the distinction between binge eating and LOC eating in the absence of an unambiguously large amount of food (

36). Youth engaging in even limited numbers of LOC eating episodes suffer from increased depressive and anxiety symptoms, greater disturbed eating cognitions, more parent reported problems, and significantly higher adiposity compared with children who do not engage in LOC eating episodes (

13,

33,

34,

37).

The prevalence of subthreshold binge and LOC eating among overweight adolescents seems to be substantial; in weight loss treatment-seeking samples, the estimates range from 20% (38) to ∼30% (39). Even among school and community samples, estimates of subthreshold binge eating range from 6% to 40% among adolescents (

40–

44). Consistent with the adult BED literature, studies have found that adolescents who report binge eating at non-diagnostic levels have increased eating-related and general psychological distress and lower self-esteem compared with non-binge eaters. In samples of overweight, treatment-seeking adolescents, binge eating severity has been positively associated with depression and anxiety (

45) and negatively correlated with self-esteem and body esteem (

38,

39,

46).

Although a number of studies suggest a relationship between binge eating and obesity in children, they are limited by their cross-sectional nature and are not informative regarding causation. However, longitudinal studies have found binge eating episodes to prospectively predict increased weight gain. In a large study of boys and girls (9 to 14 years), Field et al. (

47) found that binge eating predicted increases in BMI in boys only, after accounting for baseline BMI. Binge eating predicted weight gain and the onset of obesity in samples of adolescent girls in two prospective studies (

48,

49). In a study of 146 boys and girls (6 to 12 years at baseline), all of whom were overweight or at high risk for overweight because of a family history of obesity, binge eating at baseline predicted an additional 15% increase in body fat mass 4 years later, adjusted for the contribution of baseline fat mass (

50). Given the excess energy intake associated with binge eating in the absence of compensatory behaviors, these data suggest a possible intervention point for preventing the development of continued inappropriate weight gain: treatment of binge and LOC eating behaviors.

OBESITY IN PREVENTION

Although family-based behavioral treatment of obesity in school-aged children has shown some long-term efficacy (

51), studies of adolescent and adult weight loss and maintenance have been less successful (

51–

53), further emphasizing the need for early intervention. Prevention has been suggested as the most important approach to decreasing the obesity epidemic (

54). However, trials of obesity prevention programs have been met with limited success. Prevention programs have targeted behaviors that have been associated with overweight (e.g., television watching, soft drink consumption), or youths who are already overweight (

55,

56). However, none have targeted youths who are at high risk for increased weight gain over time based on both current weight status and disturbed eating behaviors. Behavioral factors, such as LOC eating (subjectively or objectively large binge episodes), are attractive targets because they may be amenable to change. By reducing LOC eating episodes, inappropriate weight gain attributable to LOC eating may be prevented.

The Strategic Plan for the NIH Obesity Research (

57) supports the proposition that coordinating the treatment of obesity and eating disorders may serve as a promising form of intervention. The plan notes that factors underlying binge eating in children may offer effective strategies for the prevention of obesity in high-risk populations and recommends that “the impact of strategies that simultaneously address the prevention of eating disorders as well as obesity” be determined. To date, two randomized, controlled trials testing programs for the prevention of obesity in adolescents, but which did not specifically target disordered eating, have resulted in reductions in eating disorder pathology. The first program, which included dance classes and a family-based intervention to reduce television viewing for girls, reported that participants in the treatment group trended toward greater weight loss and reported less concern about weight compared with the control group (

58). Results from the second study, “Planet Health” (

59), a school-based intervention focused on reducing inactivity, increasing physical activity, and augmenting healthful food consumption, reported reductions in obesity among girls in the treatment group (

59). They also found that the treatment group reported fewer new cases of extreme compensatory behaviors such as self-induced vomiting and laxative use (

60). These findings help to mitigate the concerns that obesity prevention programs will increase the incidence of eating disorders.

Although the impact of obesity prevention and treatment programs on eating disorders has been studied, only one research team has tested the efficacy of an eating disorder intervention in preventing obesity. Stice et al. (

61) found that healthy weight adolescent girls who participated in a dissonance-based intervention designed to reduce thin-ideal internalization, body dissatisfaction, and eating disorder symptoms were less likely to become obese 1 year later compared with girls assigned to control conditions. However, to our knowledge, no study has specifically targeted a prospectively identified risk factor for the prevention of excessive weight gain in youth at high risk for adult obesity. Studies testing the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy alone (

62–

68) or augmented with behavioral weight loss (

69,

70), interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) (

64,

65), and other forms of specialized therapies (

68,

71) for the treatment of BED in overweight adults have reported reductions in binge eating episodes, with abstinence rates ranging from 33% to 77% at final assessment. An unexpected finding of psychological treatment for BED has been that individuals with BED who cease to binge eat tend to maintain their body weight during and/or after treatment. In ∼50% of studies including psychotherapy, participants who remained abstinent from binge eating lost modest amounts of weight by their last assessment (

64,

65,

69,

70,

72). In all but one study (

63), individuals who did not remain abstinent from binge eating continued to gain weight. Despite these data, recent reviews have indicated that appreciable weight loss does not occur with psychotherapy for BED and that clinical trials are needed to obtain better measures of weight loss and maintenance (

73).

Another potential limitation of targeting binge eating for weight gain prevention is cross-sectional data in children suggesting that many individuals with LOC eating report having become overweight before their first LOC episode (

34,

74). Furthermore, a history of childhood obesity is often recalled by adults with BED (

75). For such individuals, variables other than binge eating (e.g., genetics, family environment) are likely responsible for excessive weight gain and may be less responsive to a psychological treatment targeting binge eating. However, binge eating may serve as a maintaining factor for excess body weight in such persons. In contrast, one retrospective study of adults with BED found that most individuals reported being of normal weight before their first binge episode that generally occurred during adolescence (

76). Moreover, one prospective study found that 79% of adults with BED were not obese at baseline (

26), and Stice et al. (

48,

49) found binge eating among adolescent girls to predict obesity onset in two longitudinal studies. As such, decreasing weight gain attributable to binge eating patterns among growing individuals who are at high risk for accelerated weight gain, but not severely overweight, may serve as a promising form of intervention.

Interpersonal theory, developed from the teachings of Sullivan and Meyer, posits that psychiatry involves the scientific study of people and their environment rather than the exclusive study of either the mind or of society in isolation (

77,

78). Specifically, Sullivan speculated that individual interpersonal patterns may either foster self-esteem or result in hopelessness, anxiety, and psychopathology. Bowlby extended on Sullivan's work by acknowledging the influence of early relationships on subsequent interpersonal functioning and psychopathology (

79). Thus, IPT is derived from a theory in which interpersonal functioning is recognized as a critical component of psychological adjustment and well being (

80).

IPT, originally developed for the treatment of depression in adults, is a brief therapy that focuses on improving interpersonal functioning (and, in turn, depressive symptoms) by relating symptoms to interpersonal problem areas and developing strategies for dealing with these problems (

81). The primary aims of IPT are to identify and treat an individual's depressive symptoms and one or more of the associated problem areas. Specifically, the problem areas frequently associated with depression include grief (complicated bereavement after death), interpersonal role disputes (conflict with a parent, sibling, close friend, classmate, etc.), role transitions (e.g., moving to a new school, parents divorcing, other family changes), and interpersonal deficits (social isolation or chronically poor relationships) (

81,

82). IPT focuses on current as opposed to past relationships and, in concert with this approach, makes no assumptions about the etiology of depression.

Treatment is administered in three phases. In brief, the initial phase involves assessment of the psychiatric disturbance, psychoeducation about the nature of the illness, and an assessment of the individual's interpersonal relationships. During this phase, the “sick role” is assigned to identify patients as in need of help, to relieve them of additional social pressures, and to elicit their cooperation in the recovery process (

83). The middle phase focuses on the identified interpersonal problem areas and associates the psychiatric disturbance with these problems. The termination phase involves evaluation and consolidation of therapeutic gains, acknowledgment of feelings associated with the end of treatment, and plans to maintain improvements while remaining work is outlined (

83). IPT has shown efficacy in the treatment of various types of mood disorders and several non-mood disorders (

82). For a complete description of IPT, see Weissman et al. (

82).

Building on the work in depressed adults, IPT was modified for adolescent depression (

84). Given the similarities between adolescent and adult depression and the social impairment and interpersonal difficulties associated with teen depression (

84), it is not surprising that IPT for depressed adolescents has proven efficacious in randomized trials (

85–

87). IPT for adolescents is a 12-week, once-a-week therapy that, similar to IPT for adults, aims at reducing depressive symptoms and addresses interpersonal problems associated with the onset of depression. The problem areas remain the same across both treatments (

88). Modifications from IPT for adults include the adaptation of the “limited sick role,” a discussion about the specific role transition teens experience as a result of family structural change, and inclusion of a flexible parent component. Furthermore, the treatment objectives specifically “take into account developmental tasks, including individuation, establishment of autonomy, development of interpersonal relations with members of the opposite sex and with potential romantic partners, coping with initial experiences amid death and loss, and managing peer pressure” (

88). Therapeutic techniques are geared toward the developmental stage and, thus, include use of mood rating scales and work involving basic social skills, direct perspective-taking, and negotiation (

88).

More recently, Young and Mufson (

89,

90) have adapted IPT for depressed adolescents to a prevention program for teens at high risk for full-syndrome depression. IPT-adolescent skills training (IPT-AST) is an 8-week, once-a-week group program that emphasizes psychoeducation and skill development and focuses on interpersonal issues surrounding the types of difficulties that adolescents encounter on a day-to-day basis. IPT-AST broadly addresses conflicts and transitions that are common to teens and instructs participants to use interpersonal strategies that may be applied to a number of relationships. Preliminary findings suggest that IPT-AST is effective in reducing depressive symptoms and the likelihood of major depressive disorder development (

91).

In the late 1980s, IPT was successfully modified for patients with bulimia nervosa (

92) and shortly thereafter adapted into a group format for individuals with BED (

65,

93). Both adaptations strictly adhered to the original IPT manual with the exception that the interpersonal context focused on the maintenance of the eating disorder as opposed to depression (

65,

92). In concert with interpersonal theory, it is posited that binge eating occurs in response to difficult interpersonal interactions, feelings of loneliness, or other negative emotions (

94). Indeed, individuals with binge eating often struggle with social and interpersonal deficits (

24), and, thus, it is perhaps not surprising that IPT has been shown to be efficacious in reducing binge eating and its associated psychopathology among adults with BED (

64,

65). Specifically, IPT for BED is a 15- to 20-week, once-a-week treatment that targets binge eating by directly addressing the social and interpersonal deficits proposed to cause and maintain binge eating (

80). In all other respects, IPT for BED differs little from IPT for depression.

In adapting IPT for BED, Wilfley et al. (

93) successfully modified the treatment to be delivered in a group format. IPT is particularly suitable for a group modality because it offers an ideal setting for patients to address interpersonal skills and discuss and share their social difficulties within the safe confines of the therapeutic environment (

80,

95). Because the interpersonal group is a social entity, it provides members with an “interpersonal laboratory” where they can engage socially while therapists can directly observe each patient's interpersonal style (

80,

95). Therapists can provide direct feedback to members while encouraging them to attend to their own behaviors and recognize communication techniques that may be similar to those of other patients (

80,

95). The group also provides members with the opportunity to experiment with, and practice, newly acquired skills with peers in the group by role-playing different communication skills such as clarification of the problem, elicitation of another person's point of view, and expression of their own feelings. Ultimately, therapists and members use the group milieu to examine and correct interpersonal difficulties that perpetuate binge eating (

80) and other psychiatric disturbances.

Following the group modification of Wilfley et al. (

80,

93), Mufson et al. (

95) successfully adapted IPT to be delivered in a group format to depressed adolescents. A randomized effectiveness study of IPT for depressed adolescents in school-based health clinics is currently underway. Presently, in their ongoing prevention trial, Young and Mufson (

90) are administering IPT-AST in a group format.

Although IPT has shown efficacy in the treatment of bulimia nervosa and BED, it should be noted that, despite evidence that individuals with anorexia nervosa have impaired interpersonal relationships and dysfunctional communication patterns (

96), IPT was ineffective in the treatment of the disorder in one study (

97). In a study comparing IPT and cognitive behavior therapy to a control comparison (non-specific supportive clinical management), IPT was associated with either modest or no improvement, whereas the control treatment proved to be the most effective of the three psychotherapies (

97). Such findings may be the result of the contrasting nature of a restricting eating disorder and those involving binge eating. However, more studies are needed to test IPT for the treatment of anorexia nervosa.

IPT for LOC eating may serve to slow the trajectory of weight gain in overweight or at-risk-for-overweight adolescents who are susceptible to accelerated weight gain because of their disturbed eating patterns. It has been suggested that treatments for BED may offer a potential mechanism in slowing the increase of already epidemic rates of obesity in the United States (

98). Because many adults with BED are already obese (

19), targeting adolescents who are at high risk for overweight or only slightly overweight (BMI between the 75th and 97th percentiles) and treating them with IPT may serve to reduce inappropriate weight gain in individuals who are still physically developing and whose degree and duration of obesity is more amenable to a preventative intervention.

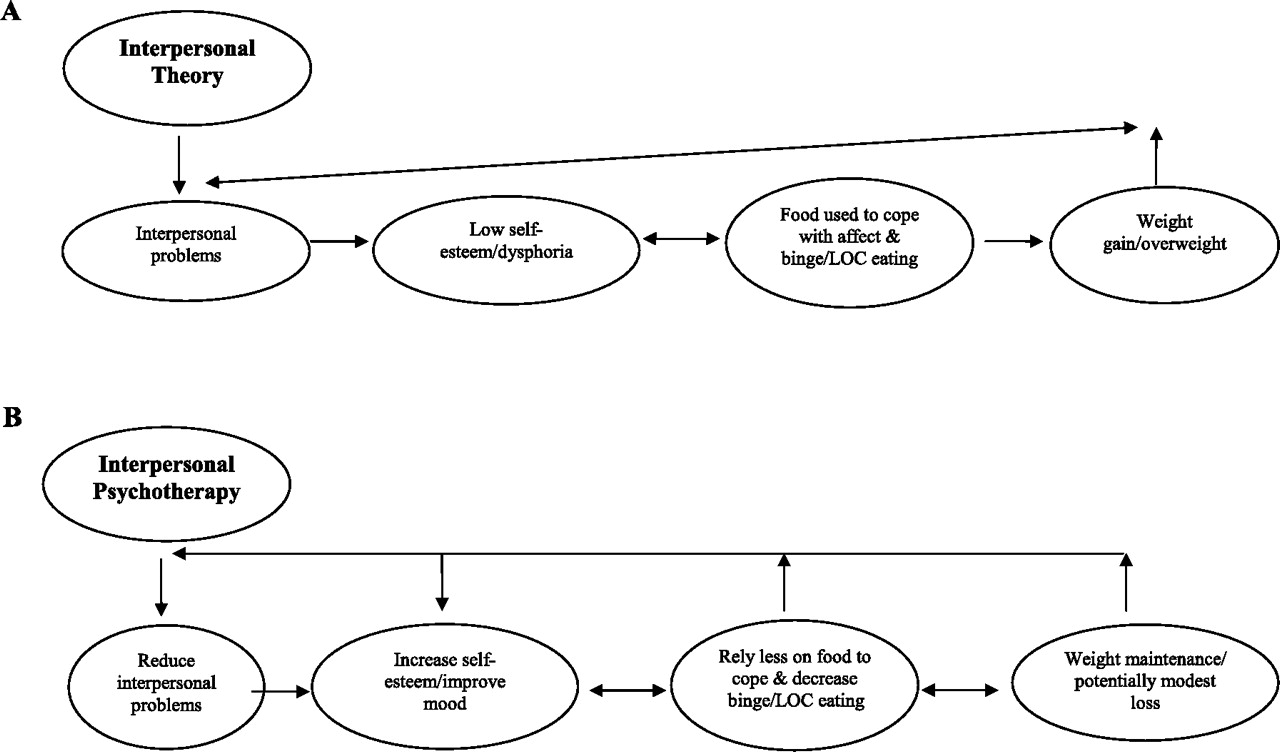

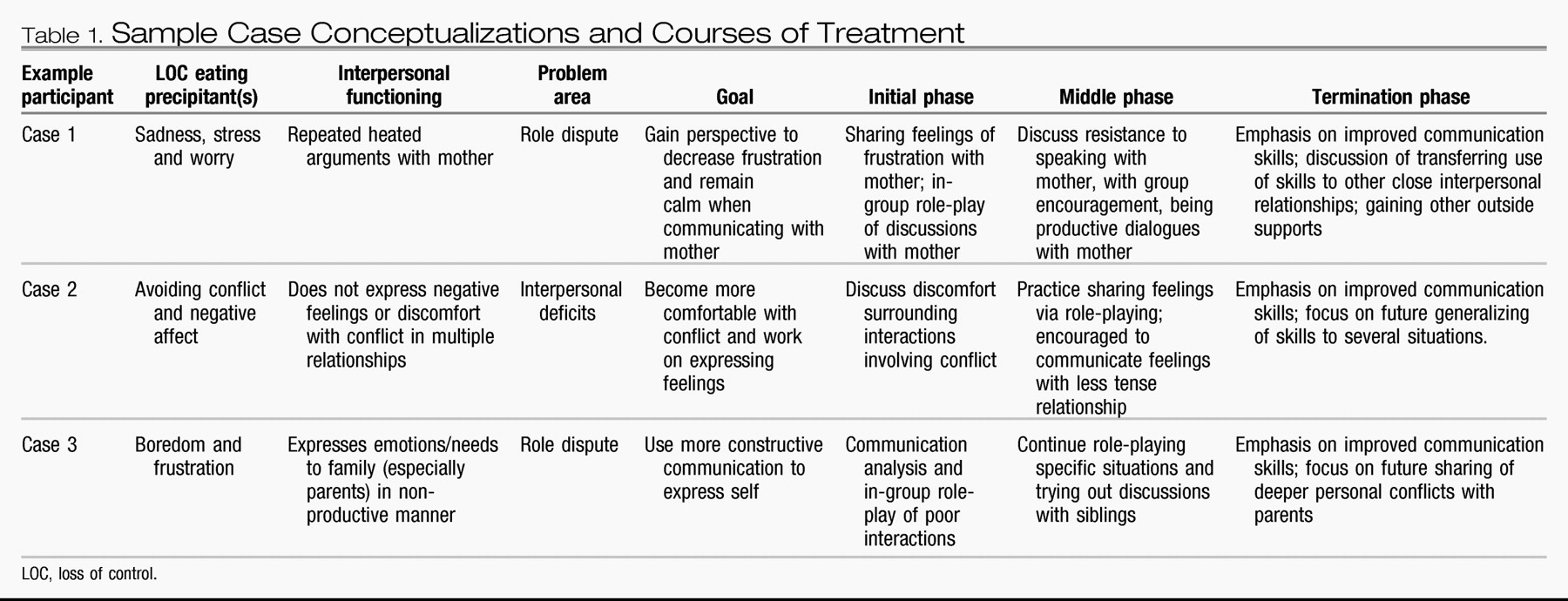

Figure 1 A and B shows the theoretical framework of the proposed intervention. In brief, interpersonal theory posits that interpersonal problems lead to low self-esteem and low mood. Food is used to cope with negative affect and LOC eating ensues. This causes excessive weight gain and overweight, which reinforces interpersonal problems (

Figure 1A).

Use of food for coping (emotional eating) may have a biological basis. There are some data to support a physiological role for food (either specific macronutrients, such as carbohydrate, or types of foods such as sweet/fat “dessert” foods) in ameliorating negative affective states (

99,

100). More recent studies are investigating the role of the opioid and dopaminergic systems in initiating or sustaining overeating episodes, particularly those caused by emotional eating (

101–

103). IPT is posited to reduce interpersonal problems, which may result in increases in self-esteem and less reliance on food to cope. As such, LOC eating decreases and the pattern of excessive weight gain is curbed (

Figure 1B). There is precedent for a psychotherapeutic approach to ameliorate abnormalities in brain function. Cognitive behavior therapy has been shown to induce changes in brain blood flow similar to that seen with the use of pharmacotherapy in patients with both phobias (

104,

105) and obsessive-compulsive disorders (

106), suggesting a convergence of pathways through which the impact of these treatments is mediated (

107). Changes in regional brain flow in patients treated for depressive disorders with both cognitive behavior therapy (

108) and IPT (

109,

110) have also been reported. In these cases, the findings are more complex, with drug treatment and psychotherapy activating different cerebral areas, suggesting that psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy may act through differing pathways (

107).

A number of factors suggest that IPT may be particularly appropriate for adolescents at high-risk for adult obesity. A primary reason is that youth frequently use peer relationships as a crucial measure of self-evaluation (

111). Because overweight teens are at risk for appearance-related teasing, rejection, and social isolation (

10), they are more likely to experience negative feelings about themselves, particularly regarding their body shape and weight, compared with healthy weight adolescents (

112–

114). Thus, the social isolation that overweight teens report may be directly targeted by IPT. Indeed, IPT has been shown to decrease negative affect and improve interpersonal and social functioning in depressed adolescents (

86). Moreover, recent studies suggest that LOC eating among youth is associated with eating in response to emotions (

37), including anger, anxiety, frustration, and depression (

115). In studies of adolescents, emotional eating is significantly correlated with constructs of disturbed eating (

116,

117) and symptoms of depression and anxiety (

117). Data also suggest that emotional eating may be associated with overweight among youth (

118) and predictive of overeating in cross-sectional structural models (

117). IPT for BED is efficacious at reducing eating in response to negative affect and disordered eating psychopathology in adults (

64,

65). Another psychotherapy targeting emotion regulation, namely dialectical behavior therapy, has also been effective in the treatment of BED (

71) and might be a reasonable approach for weight gain prevention. However, unlike dialectical behavior therapy, IPT approaches negative affect through addressing social interactions. Considerable literature exists implicating interpersonal sensitivity and difficulties as a common component among individuals with bulimic tendencies (

24,

119–

122). Measurable findings from two studies involving interactive paradigms suggest that interpersonal distress may trigger overeating (

24,

123) and potentially perpetuate binge eating. Furthermore, a number of longitudinal studies have found depressive symptoms to predict weight gain and obesity onset in children and adolescents (

124–

127). Thus, the proven efficacy of IPT in decreasing depression and depressive symptoms may serve to decrease an additional risk factor for inappropriate weight gain. Finally, IPT is posited to increase social support, which has been shown to increase weight loss and improve weight maintenance in overweight adults (

128). Thus, IPT may be a particularly suitable prevention approach for teens at high risk for adult obesity who endorse LOC eating patterns.