National concerns about pedophilia have grown because of recent high-profile child abuse and murder cases and congressional sex scandals. Recent media attention by television shows such as To Catch a Predator has fueled fears about children's vulnerability to sexual offenders. Such attention has exposed a side of pedophilia that many did not want to acknowledge existed. A pedophile is no longer seen as the isolated “dirty old man” in a raincoat preying on unsuspecting children at the local theaters or the rare flawed priest abusing an altar boy. To Catch a Predator has exposed pedophiles as our friends, neighbors, and, with the recent allegations from the House of Representatives that a US congressman engaged in “cybersex” and possibly physical sex with underage congressional pages, even political representatives. As a result of this increasing attention to sexual abuse of children, many Americans, both inside and outside the medical community, are trying to define pedophilia, the characteristics of offenders, the frequency and course of pedophilia, and the treatments for both offenders and abused children.

WHAT IS PEDOPHILIA?

Pedophilia is a clinical diagnosis usually made by a psychiatrist or psychologist. It is not a criminal or legal term, such as

forcible sexual offense, which is a legal term often used in criminal statistics (

1,

2). The Federal Bureau of Investigation's National Incident-Based Reporting System's (NIBRS) definition of forcible sexual offenses includes any sexual act directed against another person forcibly and/or against that person's will or not forcibly or against the person's will in which the injured party is incapable of giving consent (

2) By diagnostic criteria of the

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, a pedophile is an individual who fantasizes about, is sexually aroused by, or experiences sexual urges toward prepubescent children (generally <13 years) for a period of at least 6 months. Pedophiles are either severely distressed by these sexual urges, experience interpersonal difficulties because of them, or act on them (

3). Pedophiles usually come to medical or legal attention by committing an act against a child because most do not find their sexual fantasies distressing or ego-dystonic enough to voluntarily seek treatment (

3).

Generally, the individual must be at least 16 years of age and at least 5 years older than the juvenile of interest to meet criteria for pedophilia. In cases that involve adolescent offenders, factors such as emotional and sexual maturity may be taken into account before a diagnosis of pedophilia is made (

3). Pedophiles usually report that their attraction to children begins around the time of their puberty or adolescence, but this sexual attraction to children can also develop later in life (

3–

9). If the clinical diagnosis of pedophilia is based on a specific act, it usually is not solely the result of intoxication or caused by another state or condition that may affect judgment, such as mania (

3,

10–

12). These cases are distinguished from pedophilia by the act being contrary to the individual's usual sexual behaviors and fantasies (

3,

10–

12). Some studies have found that as many as 50% to 60% of pedophiles also have a substance abuse or dependence diagnosis, but what is important is that their attraction to children is present in both the sober and the intoxicated state (

12,

13).

The course of pedophilia is usually long term (

3,

5,

9,

14,

15). In a study that examined the relationship between age and types of sexual crimes, Dickey et al. (

14) found that up to 44% of pedophiles in their sample of 168 sex offenders were in the older adult age range (age, 40–70 years). When compared with rapists and sexual sadists, pedophiles comprise 60% of all older offenders, indicating that pedophiles offend in their later years at a greater rate than other sexual offenders (

14).

Technically, individuals who engage in sexual activities with pubescent teenagers under the legal age of consent (ages 13–16 years) are known as hebophiles (attracted to females) or ephebophiles (attracted to males) (

15–

17). The term

hebophilia (also spelled as

hebephilia) is becoming a generic term to describe sexual interest in either male or female pubescent children (

16–

19). Distinctions noted in the literature between hebophiles and pedophiles are that hebophiles tend to be more interested in having reciprocal sexual affairs or relationships with children, are more opportunistic when engaging in sexual acts, have better social functioning, and have a better posttreatment prognosis than pedophiles (

17,

18). The term

teleiophile applies to an adult who prefers physically mature partners (

16,

19). There is also a subclassification of pedophilia known as

infantophilia, which describes individuals interested in children younger than 5 years (

20). These distinctions are important in understanding current research about paraphilias, selection criteria for studies of sexual behavior, and tests that gauge sexual interest (eg, plethysmography).

Pedophiles may engage in a wide range of sexual acts with children. These activities range from exposing themselves to children (exhibitionism), undressing a child, looking at naked children (voyeurism), or masturbating in the presence of children to more intrusive physical contact, such as rubbing their genitalia against a child (frotteurism), fondling a child, engaging in oral sex, or penetration of the mouth, anus, and/or vagina (

3,

5,

7,

9). Generally, pedophiles do not use force to have children engage in these activities but instead rely on various forms of psychic manipulation and desensitization (eg, progression from innocuous touching to inappropriate touching, showing pornography to children) (

1,

5,

17,

21). When confronted about engaging in such activities, pedophiles commonly justify and minimize their actions by stating that the acts “had educational value,” that the child derived pleasure from the acts or attention, or that the child was provocative and encouraged the acts in some way (

1,

3,

9,

22–

24). A US Department of Justice manual for law enforcement officers identifies 5 common psychological defense patterns in pedophiles: (1) denial (eg, “Is it wrong to give a child a hug?”), (2) minimization (“It only happened once”), (3) justification (eg, “I am a boy lover, not a child molester”), (4) fabrication (activities were research for a scholarly project), and (5) attack (character attacks on child, prosecutors, or police, as well as potential for physical violence) (

1).

Fifty percent to 70% of pedophiles can be diagnosed as having another paraphilia, such as frotteurism, exhibitionism, voyeurism, or sadism (

7,

12,

25). Pedophiles are approximately 2.5 times more likely to engage in physical contact with a child than simply voyeuristic or exhibitionistic activities (

7). Typically, pedophiles engage in fondling and genital manipulation more than intercourse, with the exceptions occurring in cases of incest, of pedophiles with a preference for older children or adolescents, and when children are physically coerced (

5–

7).

Child molestation is not a medical diagnosis and is not necessarily a term synonymous with pedophilia (

5,

7,

15,

17,

26). A child molester is loosely defined as any individual who touches a child to obtain sexual gratification with the specifier that the offender is at least 4 to 5 years older than the child (

15,

26). The age qualifier is added to eliminate developmentally normal childhood sex play (eg, two 8-year-olds “playing doctor”) (

26). By this definition, a 13-year-old who touches an 8-year-old would be considered a child molester but would not meet criteria to be a pedophile. The NIBRS data on juvenile sexual assaults found that 40% of assaults against children younger than 12 years were committed by juveniles, with the most frequent age of the offenders being 14 years old (

2). Data from the study by Abel and Harlow (

15) showed that 40% of child molesters, who were later diagnosed as having pedophilia, had molested a child by the time they were 15 years old. An estimated 88% of child molesters and 95% of molestations (one person, multiple acts) are committed by individuals who now or in the future will also meet criteria for pedophilia (

9,

15). Pedophilic child molesters on average commit 10 times more sexual acts against children than nonpedophilic child molesters (

15).

In general, most individuals who engage in pedophilia or paraphilias are male (

2–

7,

9,

10). There was a time when it was believed that females could not be pedophiles because of their lack of long-term sexual urges unless they had a primary psychotic disorder (

4,

22). When women were studied for sexually inappropriate behavior directed toward children, these behaviors were classified as “sexual abuse” or “molestation” but not pedophilia (

6,

7,

27). From federal data on sexual crimes, females were reported to be the “molester” in 6% of all juvenile cases (

2). The study by Abel and Harlow of 4007 “child molesters” found 1% to be female, but the authors believed this number was low because of the systematic underreporting of women for molestation (

15,

27). One reason why acts of pedophilia committed by women are underreported is that many acts are not recognized because they occur during the course of regular “nurturing or care-giving activities,” such as when bathing and dressing children (

22,

27). Another reason is that when adult women engage in sexual acts with adolescent boys, others do not perceive this activity as abuse but rather a fortunate rite of passage (

27). The law sees it otherwise.

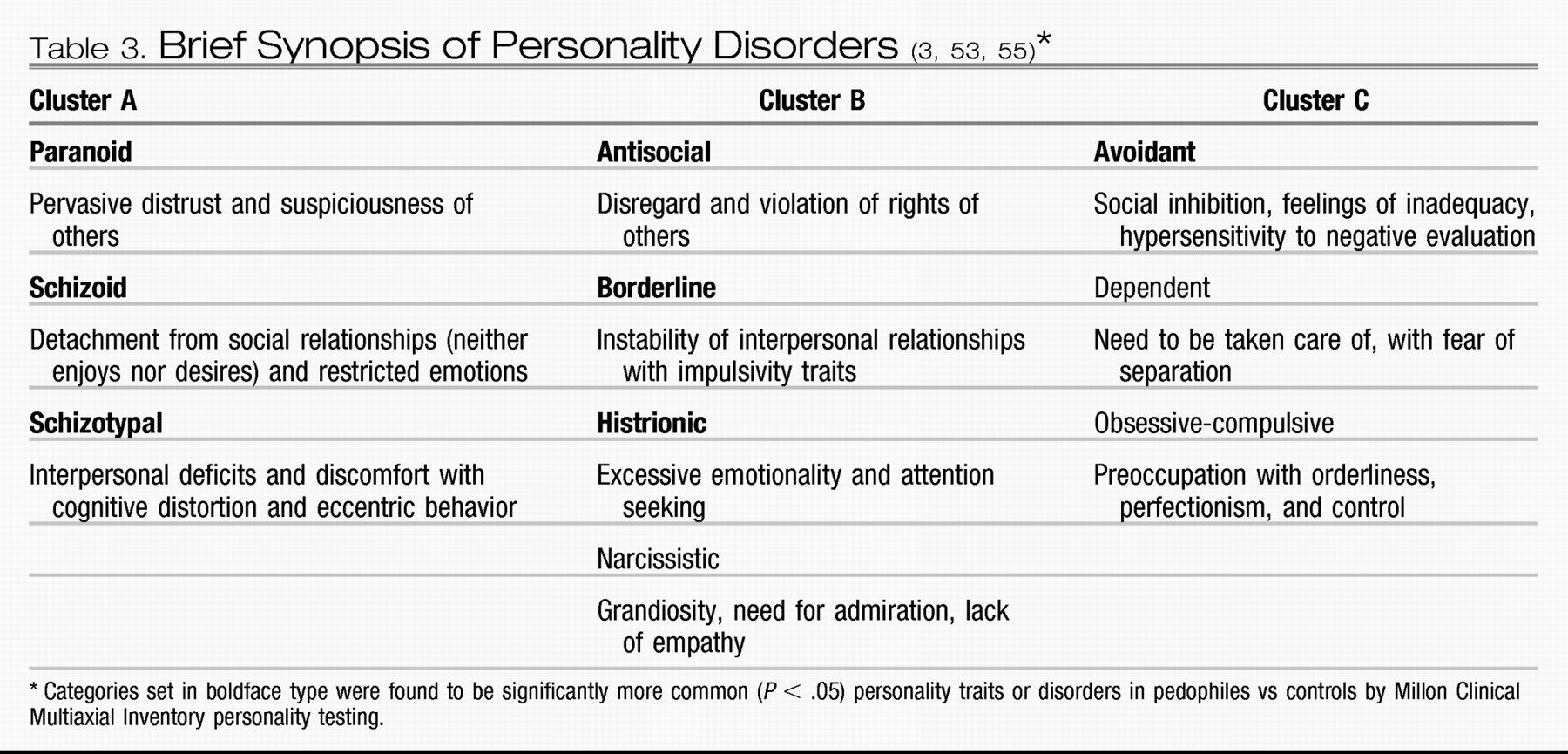

Pedophilic women tend to be young (22–33 years old); have poor coping skills; may meet criteria for the presence of a psychiatric disorder, particularly depression or substance abuse; and frequently also meet criteria for being personality disordered (antisocial, borderline, narcissistic, dependent) (

27) (

Table 1). In incidents in which women are identified as being involved in sexually inappropriate acts with children, there is an increased chance of a male pedophile being involved as well (

7). When a male co-offender is involved, usually more than 1 child is involved. Molested children tend to be both male and female and are more likely to be related to the offender. In these cases, the female offender is also likely to have committed a nonsexual offense and a sexual offense (

28). Cases that involve a male codefendant rightfully or wrongfully often do not result in the woman being charged (

27). Unless specifically stated, the rest of this article deals with male pedophiles because most studies are based on male offenders.

CATEGORIES OF PEDOPHILES

Pedophiles are subdivided into several classifications. One of the first distinctions made when classifying pedophiles is to determine whether they are “exclusively” attracted to children (exclusive pedophile) or attracted to adults as well as children (nonexclusive pedophile). In a study by Abel and Harlow (

15) of 2429 adult male pedophiles, only 7% identified themselves as exclusively sexually attracted to children, which confirms the general view that most pedophiles are part of the nonexclusive group.

Pedophiles are usually attracted to a particular age range and/or sex of child. Research categorizes male pedophiles by whether they are attracted to only male children (homosexual pedophilia), female children (heterosexual pedophilia), or children from both sexes (bisexual pedophilia) (

3,

6,

10,

29). The percentage of homosexual pedophiles ranges from 9% to 40%, which is approximately 4 to 20 times higher than the rate of adult men attracted to other adult men (using a prevalence rate of adult homosexuality of 2%–4%) (

5,

7,

10,

19,

29,

30). This finding does not imply that homosexuals are more likely to molest children, just that a larger percentage of pedophiles are homosexual or bisexual in orientation to children (

19). Individuals attracted to females usually prefer children between the ages of 8 and 10 years (

3,

5,

31). Individuals attracted to males usually prefer slightly older boys between the ages of 10 and 13 years (

3,

5). Heterosexual pedophiles, in self-report studies, have on average abused 5.2 children and committed an average of 34 sexual acts vs homosexual pedophiles who have on average abused 10.7 children and committed an average of 52 acts (

15). Bisexual offenders have on average abused 27.3 children and committed more than 120 acts (

15). A study by Abel et al. (

32) of 377 nonincarcerated, non-incest-related pedophiles, whose legal situations had been resolved and who were surveyed using an anonymous self-report questionnaire, found that heterosexual pedophiles on average reported abusing 19.8 children and committing 23.2 acts, whereas homosexual pedophiles had abused 150.2 children and committed 281.7 acts. These studies confirm law enforcement reports about the serial nature of the crime, the large number of children abused by each pedophile, and the underreporting of assaults (

1). Studies that used self-reports and polygraphs show that pedophiles currently in treatment underreport their current interest in children and past behaviors (

33,

34).

Another common pedophilic specifier is whether the abused children are limited to family members (ie, incest) (

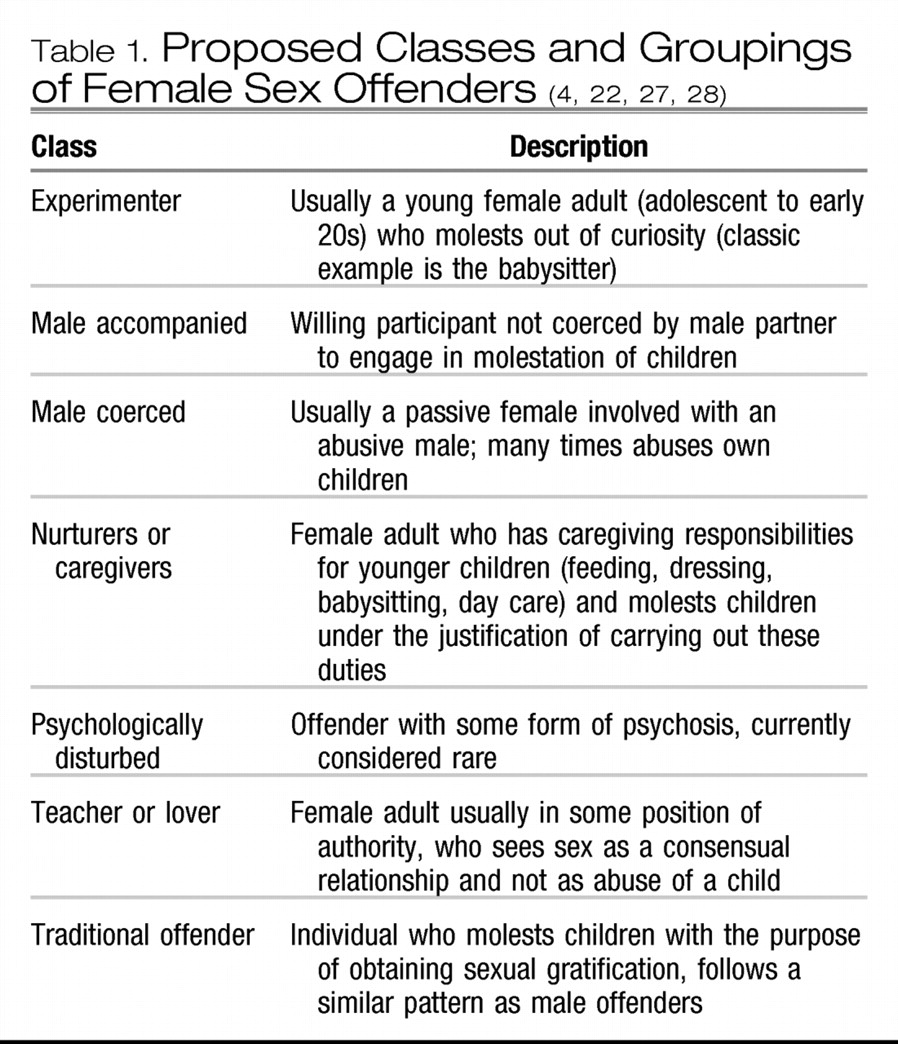

6). Federal data show that 27% of all sexual offenders assaulted family members. Fifty percent of offenses committed against children younger than 6 years were committed by a family member, as were 42% of acts committed against children 6 to 11 years old and 24% against children 12 to 17 years old (

2). The study by Abel and Harlow (

15) found that 68% of “child molesters” had molested a family member; 30% had molested a stepchild, a foster child, or an adopted child; 19% had molested 1 or more of their biologic children; 18% had molested a niece or nephew; and 5% had molested a grandchild. In the study by Abel et al. (

32) of anonymous nonincarcerated offenders, heterosexual incest pedophiles had abused 1.8 children and committed 81.3 acts, whereas homosexual incest pedophiles had abused 1.7 children and committed 62.3 acts.

Pedophiles are also classified as to whether child pornography and/or a computer was used to engage the child in sexual activity (

33). Individuals engaging in computer-based pedophilia are generally classified into 5 categories: (1) the stalkers, who try to gain physical access to children; (2) the cruisers, who use the Internet for direct reciprocated sexual pleasure without physical contact (eg, chat rooms); (3) the masturbators, who use the Internet for more passive gratification (viewing child pornography); (4) the networkers or swappers, who communicate with other pedophiles and trade information, pornography, and children; and (5) a combination of the previous 4 types (

35–

38). Deirmenjian (

38) further subdivides the stalking category into the “trust-based seductive approach” and the “direct approach,” in which sexually explicit themes are discussed from the beginning of the communication. There is a concern that the perceived anonymity of the Internet results in people being more disinhibited and therefore willing to engage in acts they would not otherwise consider (

1,

38). Studies and case reports indicate that 30% to 80% of individuals who viewed child pornography and 76% of individuals who were arrested for Internet child pornography had molested a child (

1,

21). It is difficult to know how many people progress from computerized pedophilia to physical acts against children and how many would have progressed to physical acts without the computer being involved (

39). It is interesting that the NIBRS data from 2000 show that most child pornography crimes reported did not involve a computer or the Internet but were related to photographs, magazines, and videos (

40). Recent studies have noted a decrease in Internet-related child pornography because of pressure from Internet “watchdog” groups and an increased police presence on the Internet (

41,

42).

GAINING ACCESS TO CHILDREN

For nonparental incest and nonviolent incidences of pedophilia, the child knows the offender (eg, neighbor, relative, family friend, or local individual with authority) an estimated 60% to 70% of the time (

2,

5,

7). Pedophiles often intentionally try to place themselves in a position where they can meet children and have the opportunity to interact with children in an unsupervised way, such as when babysitting, doing volunteer work, doing hobbies, or coaching sports (

5,

7,

9,

27,

36,

50). Pedophiles usually obtain access to children through means of persuasion, friendship, and behavior designed to gain the trust of the child and parent (

5). Individuals in the Canadian study by Bagley et al. (

46), who experienced long-term abuse, reported abuse starting at an earlier age (8.2 years on average compared with 11.5 years for single abuse) and were more likely to be abused by a parental figure such as a stepfather or neighbor. Female and younger children are often molested in their own home or the residence of the offender, whereas male and older children are most likely to be molested outside their home in locations such as roadways, fields or woods, schools, or motels or hotels (

2,

5). In cases of violent assaults (ie, requiring force), approximately 70% of the time the child does not know the pedophile (

7).

Pedophiles may target certain types of families when looking for children to abuse. The study by Bagley et al. (

46) noted that the parents of children who had been abused by pedophiles had notable characteristics, such as a lower overall education and a higher rate of absenteeism from home. The mothers of abused children had less education than control group mothers and were more likely to be single parents. A significant number of fathers in the molested group were absent for at least 3 years before the child turned 16 years old. The fathers themselves tended to be of lower socioeconomic and educational levels than controls, but this finding was not statistically significant probably because a substantial amount of data were missing concerning the absentee fathers (

46). Similar findings occurred in the study by Conte et al. (

51) (n = 20) in which pedophiles were interviewed about how they selected the children they abused. The pedophiles stated they would choose vulnerable individuals (eg, children living in a divorced home, emotionally needy or unhappy children) and/or children who were receptive to their advances, even if that child did not meet the pedophile's usual physical pattern of attraction (

51).

PERSONALITY TRAITS OF THE PEDOPHILE

It is difficult to present a classic personality pattern for pedophilia because of the various subgroups that exist (

53). Some individuals who have pedophilia are able to present themselves as psychologically normal during examination or superficial encounters, even though they have severe underlying personality disorders (

6,

46,

54). Studies have shown that people with pedophilia generally experience feelings of inferiority, isolation or loneliness, low self-esteem, internal dysphoria, and emotional immaturity. They have difficulty with mature age-appropriate interpersonal interactions, particularly because of their reduced assertiveness, elevated levels of passive-aggressivity, and increased anger or hostility (

5,

23,

27,

28,

55–

63). These traits lead to difficulty dealing with painful affect, which results in the excessive use of the major defense mechanisms of intellectualization, denial, cognitive distortion (eg, manipulation of fact), and rationalization (

6,

24,

46,

53,

56,

62). Even though pedophiles often have difficulty with interpersonal relationships, 50% or more will marry at some point in their lives (

15,

32,

53,

55,

56,

61,

64).

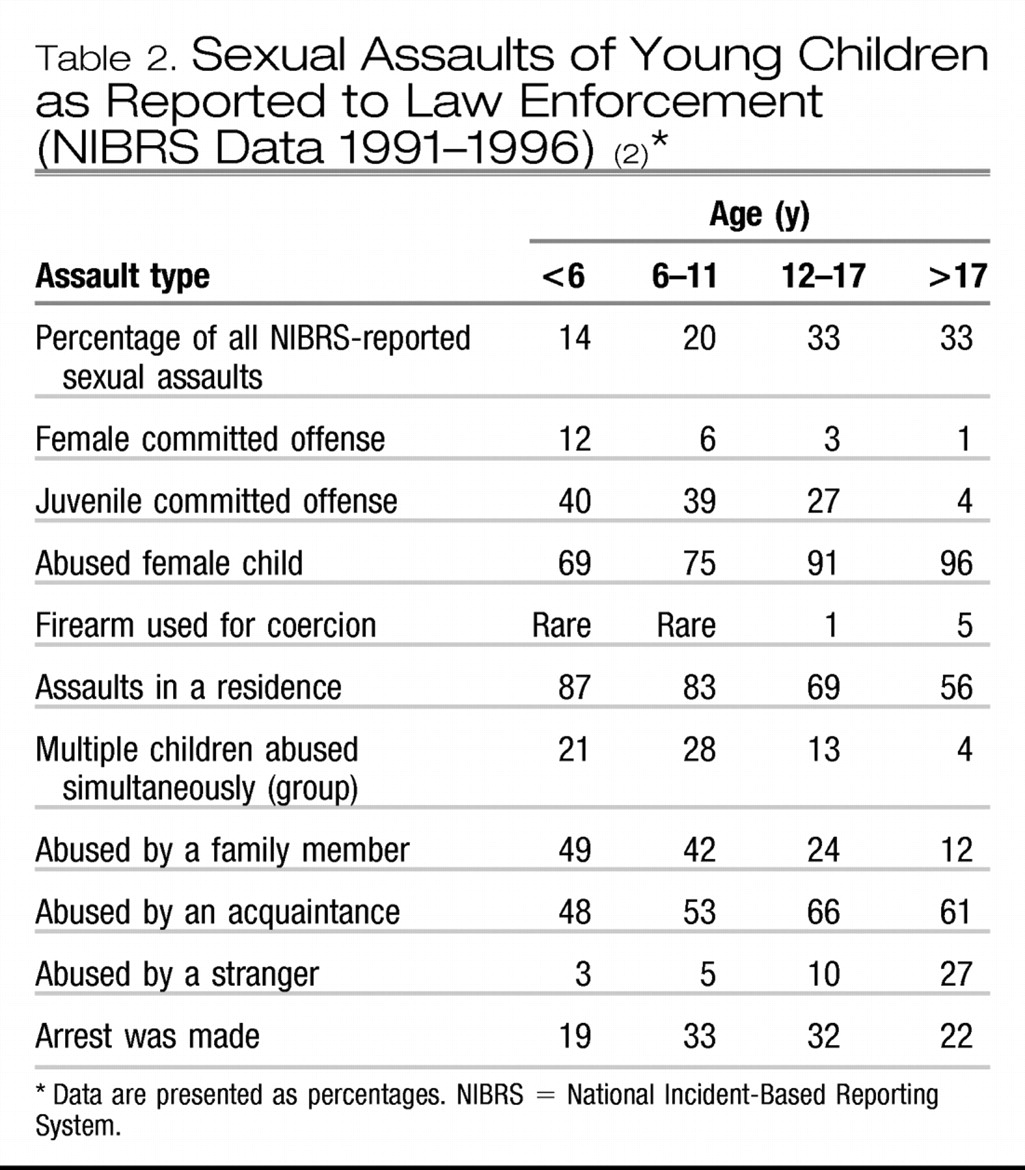

It is common for people who are diagnosed as having pedophilia to also experience another major psychiatric disorder (affective illness in 60%–80%, anxiety disorder in 50%–60%) and/or a diagnosable personality disorder (70%–80%) at some time in their life (

7,

12,

63). An estimated 43% of pedophiles have cluster C personality disorders, 33% have cluster B personality disorders, and 18% have cluster A personality disorders (

23,

31,

53,

55) (

Table 3). A study by Curnoe and Langevin (

65), using the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory with pedophiles and other “deviant fantasizers” (n = 186), showed significantly increased scores on the infrequency scale, the psychopathic deviance scale, the masculinity-femininity scale, the paranoia scale, and the schizophrenia scale. These results suggest that pedophiles are more socially alienated and less emotionally stable than most other people, traits commonly seen in patients with cluster A and B personality disorders (

65). Many pedophiles also demonstrate narcissistic, sociopathic, and antisocial personality traits. They lack remorse and an understanding of the harm their actions cause (

23,

53).

The notion of impulsivity as a personality factor in pedophiles is often debated. Pedophiles frequently report trouble controlling their behavior, although it is rare for them to spontaneously molest a child. The fact that 70% to 85% of offenses against children are premeditated speaks against a lack of perpetrator control (

23,

55). Cohen et al. (

55) compared 20 heterosexual pedophiles to a control group and found that pedophiles demonstrated elevated scores for harm avoidance, with no elevation for novelty seeking on the Temperament and Character Inventory. Cohen et al. suggest that, instead of viewing pedophilia as the result of an impulse-aggressive trait (eg, unplanned with no consideration for consequences), it should be viewed as the result of a compulsive-aggressive trait (planned with the intention of relieving internal pressures or urges) (

55).

DETECTING PEDOPHILES FOR RESEARCH PURPOSES

Historically, for research purposes, the most reliable mechanism for determining pedophilia is by use of phallometric or plethysmographic testing procedures (

78). These procedures involve presenting various types of stimuli (pictures, movies, audio tapes) to the subject and then measuring either blood volume changes or circumference changes of the penis (

11,

78). Volumetric changes in penile blood are generally thought to be more accurate in determining lower levels of sexual responses or arousal than circumference measurements (

11). The problems with plethysmography are that it is invasive and expensive, requires the presence of sexually explicit material, is not applicable to females, requires functioning male genitalia (medical cause of impotence, such as hypertension or diabetes, could affect results), and can potentially be tricked (eg, by looking at images but thinking about something else) (

5,

78). An additional limiting factor to the current use of plethysmography in pedophilic research in the United States is that the images of “sexually explicit material of children” needed to perform the test are themselves considered illegal by most state laws and under federal pornography guidelines. Possession of such material can lead to legal trouble for researchers.

A relatively new testing procedure known as the Abel Assessment for Sexual Interest (AASI) is beginning to be used in conjunction with or in lieu of traditional phallometric measurements (

34,

78). The AASI is based on a self-report questionnaire and computer-based visual reaction times, which measure how long a subject looks at various clothed photographs of a standardized sample of children and adults (

34,

78–

80). The AASI is reported to be able to discriminate 21 sexual interest categories and has been shown to be as valid as plethysmography for detecting homosexual pedophiles (

34,

78–

81). The AASI has better validity for detecting heterosexual hebophiles than plethysmography but is not accurate for pedophiles interested in young girls (

78). Although not foolproof, the advantages of the AASI are that it uses standardized nonpornographic photographs, requires only 1 to 2 hours to administer, requires no special equipment except a computer, can be performed almost anywhere, and is less invasive and intrusive to the subject than plethysmography.

EFFECTS OF ABUSE ON CHILDREN

Generally, abused children experience the greatest psychological damage when the abuse occurs from father figures (close neighbors, priests or ministers, coaches) or involves force and/or genital contact (

5,

45,

46). The specific long-term effects on abused children as they grow into adulthood are difficult to predict. Some individuals adapt and have a higher degree of resilience, whereas others are profoundly and negatively changed. Studies have found that the children abused by pedophiles have higher measures of trauma, depression, and neurosis on standardized psychometric testing (

45,

46). Individuals who experience long-term abuse are significantly more likely to have affective illness (eg, depression), anxiety disorders (eg, generalized anxiety disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder, panic attacks), eating disorders (anorexia in females), substance abuse, personality disorders, and/or adjustment disorders and to make suicidal gestures or actually engage in serious suicide attempts than those who are not abused (

43,

46,

82,

83). These children often have problems with long-term intimacy and feelings of guilt and shame over their role in the incident (

84). In addition, sexually abused children have lower levels of education and a higher frequency of unemployment (

46). It is difficult to determine whether the higher frequency of unemployment is because of the sexual abuse or whether the unemployment as an adult is a marker for a trait that led the abused child to be seen as vulnerable as a child (

46).

We have clinically treated 10 adult men who were molested by a priest or minister. Many of these men reported initially liking the relationship with the clergyman because of the attention they received and having a special relationship with a person of power and respect. Later, these men reported feeling rejected, abandoned, and betrayed. They all reported multiple sexual acts. Five were “passed around” to other pedophilic clergy, who also engaged in multiple sexual acts with them. Common features seen in the abused men included guilt, anger, and confusion about the abuse. Eight of the abused men had either treatment-refractory or recurrent depression, 7 had divorced at least twice, 6 had made serious suicide attempts, and 4 had alcohol or drug dependency issues. All reported fear of isolation from others, shame, and a fear of emotional dependency on others. Five reported they were gay or bisexual, whereas 3 of the remaining 5 had difficulty with both emotional and physical intimacy with their spouses.

TREATMENT OF SEXUAL OFFENDERS

No treatment for pedophilia is effective unless the pedophile is willing to engage in the treatment. Individuals can offend again while in active psychotherapy, while receiving pharmacologic treatment, and even after castration (

17). Currently, much of the focus of pedophilic treatment is on stopping further offenses against children rather than altering the pedophile's sexual orientation toward children. Schober et al. (

34) found that individuals still showed sexual interest in children, as measured by the AASI, even after a year of combined psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy, whereas the pedophiles' self-reported frequency of urges and masturbation had decreased. These findings indicate that the urges can be managed, but the core attraction does not change (

34,

64). Other interventions designed to manage these pedophilic urges include careful forensic and therapeutic monitoring and reporting, use of testosterone-lowering medications, use of SSRIs, and surgical castration (

34,

64).

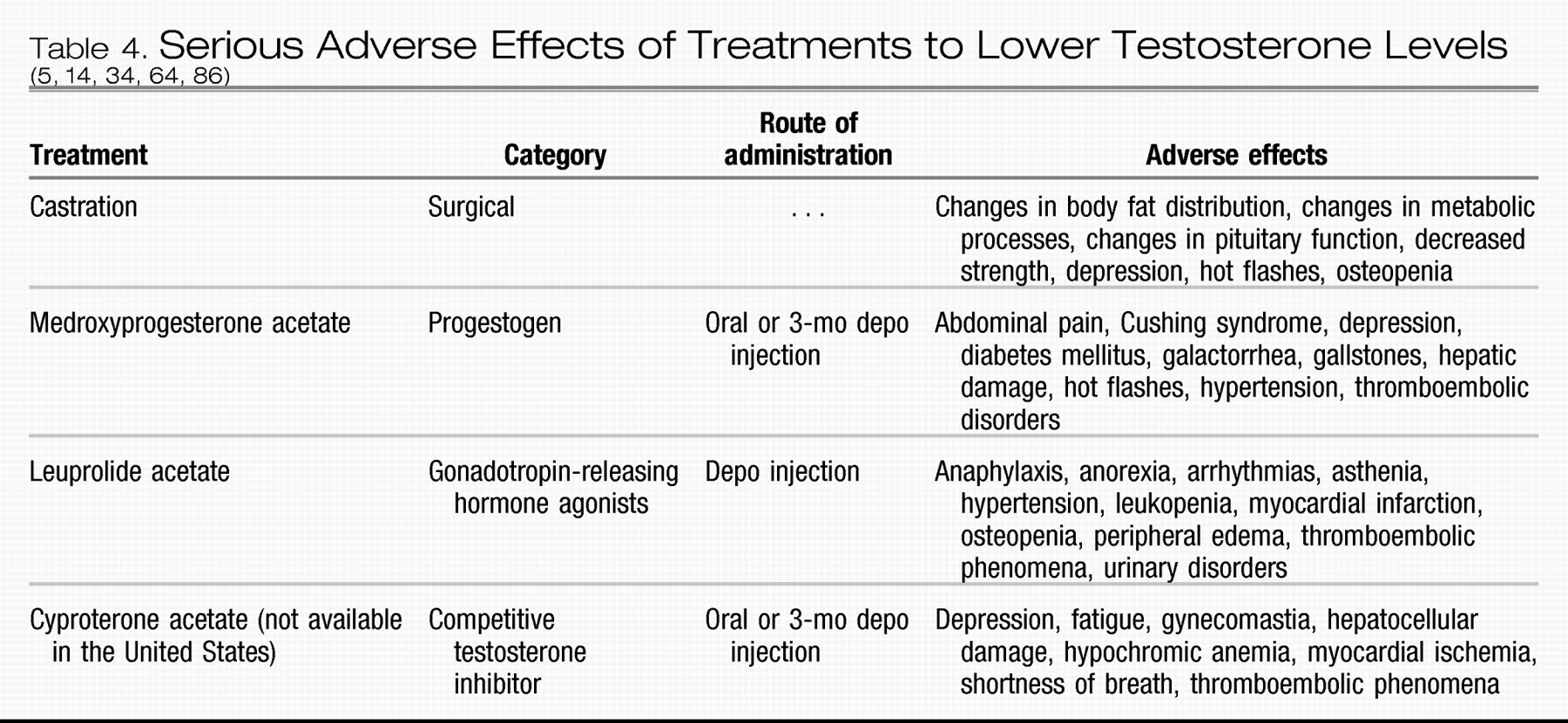

A popular treatment option is testosterone suppression by pharmacologic means (eg, antiandrogenic therapy or chemical castration). We are aware of only one state (Texas) that will pay for physical castration of sexual offenders but not for long-term chemical castration (

85). Although physical castration seems definitive in preventing repeated sexual offenses, some physically castrated pedophiles have restored their potency by taking exogenous testosterone and then abused again (

17). Chemical castration has many advantages over physical castration. It requires follow-up visits, continuous monitoring, and psychiatric reevaluation to continue the medication and is reversible for health reasons (

64). Agents such as medroxyprogesterone acetate, leuprolide acetate, cyproterone acetate, luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone, and gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists have all been studied as forms of treatment and all work by suppressing testosterone levels (

5,

14,

34,

64,

86) (

Table 4). Depending on the mechanism of action of the agent used, it can take from 3 to 10 months before one sees a decrease in sexual desire (

64). Medroxyprogesterone acetate, leuprolide acetate, and gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists have been shown to decrease both deviant and nondeviant sexual drives and behaviors in paraphilic individuals (

5,

14,

34,

64,

86). Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists are becoming the standard of treatment because they have fewer adverse effects and improved efficacy over the older treatments such as medroxyprogesterone acetate (

7,

34,

43,

64). Reduced libido also seems to make some offenders more responsive to psychotherapy (

5). A drawback to hormone therapy vs castration is its annual cost, which can range from $5000 to $20,000 a year (

34,

87).

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors represent a non-hormonal treatment that has been suggested for paraphilias in general and specifically for pedophilia (

7,

17,

22,

34,

64,

76,

86). Currently, no blinded placebo-controlled trials have shown that SSRIs are effective for the treatment of pedophilia; however, open-label trials and case reports suggest that SSRIs may be helpful for treating pedophilia (

7,

17,

22,

34). These medications can provide a helpful adjunct to structured regulated surveillance, psychotherapy, and hormonal treatment. Part of the basis for the use of an SSRI is the neuropsychiatric data that show serotonin abnormalities and impulse control problems in some pedophiles. These findings are similar to those found in patients with OCD, who respond to SSRIs (

22,

34,

44). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors seem to lessen the sexual ruminations and increased sexual urges that pedophiles report related to situational stress and internal discord (

7). The diminished sexual drive produced by SSRIs, which is usually perceived as an adverse effect of the medication, may be beneficial for pedophiles (

7).

Medications that may be used in the future to treat pedophiles include topiramate and other medications that modulate the voltage-dependent sodium or calcium channel potentiation of γ-aminobutyric acid neurotransmission and/or block kainite/α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionate glutamate receptors (

88–

90). Topiramate has been shown to be useful in treating addictions such as gambling, kleptomania, binge eating, and substance use (

88–

90). Although no prospective clinical trials have documented its effectiveness in pedophiles, several case reports have recently described topiramate's effectiveness in reducing or stopping unwanted sexual behaviors in paraphilic and nonparaphilic (eg, prostitutes, compulsive viewers of general pornography, patients with compulsive masturbation) patients. Dosing has ranged from 50 to 200 mg. Two to 6 weeks are required before decreases in driven sexual behavior occur (

88–

90). Although no clear mechanism of action has been identified, theories that have been proposed to explain topiramate's mechanism of action include a decrease of dopamine release in the midbrain and direct effects on the γ-aminobutyric activity in the nucleus accumbens (

88).

Psychotherapy is an important aspect of treatment, although debate exists concerning its overall effectiveness for long-term prevention of new offenses (

47,

91–

93). Psychotherapy can be individual, group based, or, most commonly, a combination of the two. The general strategy toward psychotherapy with pedophiles is a cognitive behavioral approach (addressing their distortions and denial) combined with empathy training, sexual impulse control training, relapse prevention, and biofeedback (

7,

17,

53,

94,

95). Several studies have demonstrated that the best outcomes in preventing repeat offenses against children occur when pharmacological agents and psychotherapy are used together (

34). A controversial approach is the use of aversion conditioning and masturbatory reconditioning to change the individual's sexual orientation away from children. Similar techniques were used with homosexual adults in the middle to late 20th century. Although some clinicians claimed to be able to reorient homosexual people to heterosexuality and to decrease the pleasure reward cycle of pedophiles with these techniques, such methods are no longer used at reputable treatment centers (

7,

43).

REPEATED OFFENSES

Just as the prevalence of pedophilia is not accurately known, the rate of recidivism against a child is also unknown. Recidivism is a term with many definitions, which affect reported rates of repeated offenses. For example, some studies look at additional arrests for any offense, others only look at arrests for sexual crimes, and some only look at convictions, whereas others analyze self-reported reoffenses (

31,

94,

96). The data on recidivism underestimate its rate because many treatment studies do not include treatment dropout figures, cannot calculate the number of repeated offenses that are not reported, and do not use polygraphs to confirm self-reports (

96). Another complicating factor is the period during which the data are collected. Some studies report low recidivism rates, but these numbers apply to individuals followed up during periods of active treatment only or for short periods after treatment is terminated (eg, 1–5 years) (

96,

97).

The published rates of recidivism are in the range of 10% to 50% for pedophiles depending on their grouping (

7,

16,

17,

31,

43,

94,

96–

98). Some studies have reported that certain classes of pedophiles (eg, homosexual, nonrelated) have the highest rate for repeated offending compared with other sex offenders (

17,

99). Generally, homosexual and bisexual pedophiles have higher recidivism rates than heterosexual pedophiles (

31,

94,

98,

100). Incest pedophiles generally have the lowest rate of reoffense (

98). The more deviant the sexual practices of the offender, the younger the abused child; the more sociopathic or antisocial personality traits displayed, the greater the treatment noncompliance; and the greater the number of paraphilic interests reported by the offender, the higher the likelihood of reoffense (

16,

91,

94,

99–

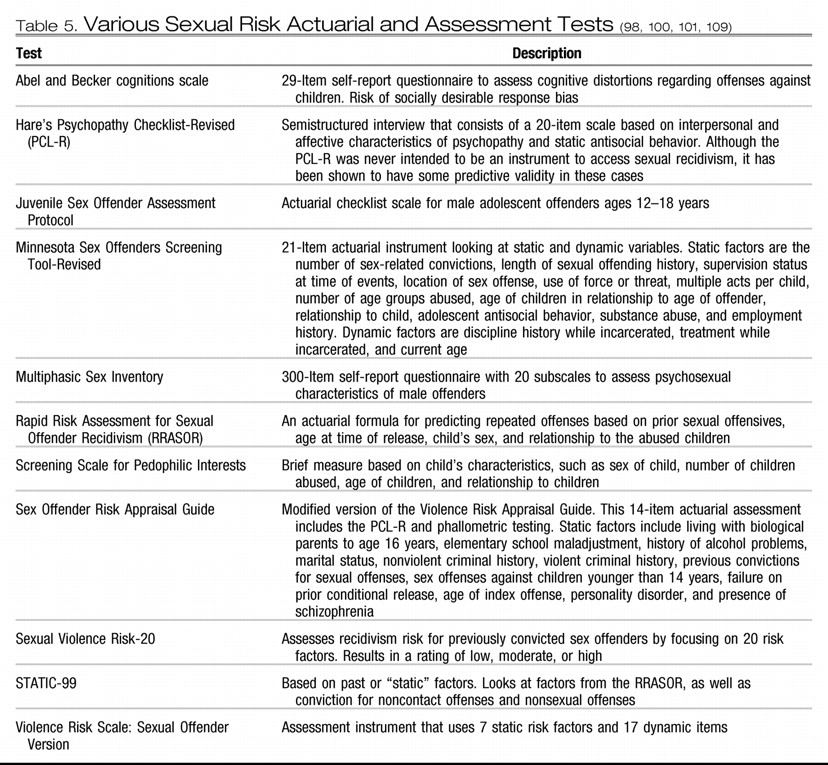

102). Several actuarial and self-report tests have been designed to help physicians and law enforcement officers predict which individuals are at higher risk for repeated offense, but currently no single test or combination of tests can accurately identify the future activity of an individual (

49,

91,

96,

100–

110) (

Table 5).

In a study of the characteristics of individuals who repeatedly offend, Beier (

31) found that one fourth of heterosexual pedophiles (n = 62) and half of homosexual and bisexual pedophiles (n = 59) repeated offenses (as evidenced by repeated arrests for a sexual violation or a self-reported violation) during a 25- to 32-year period. Beier noted the characteristics that predict repeated offenses for homosexual and bisexual pedophiles were (1) being exclusive pedophiles, (2) being of average to above average intelligence, (3) being middle-aged at the time of the primary offense, (4) abusing children aged 12 to 14 years, (5) engaging in coitus at an earlier age than non-repeat offenders, and (6) having a diagnosed personality disorder (

31). Repeat offending heterosexual pedophiles were characterized as (1) having poor family relationships and support, (2) having engaged in intercourse before the age of 19 years, (3) being middle-aged or older at the time of the index case, and (4) having initially abused young children (3–5 years old) who were unknown to them (

31). Most of the repeated offenses occurred 10 years after the initial offense. Whether this delay was initially due to successful treatment, incarceration, or other factors is unknown (

31).