A Person-Centered Approach to Clinical Practice

Abstract

A PERSON IS MORE THAN HIS OR HER SYMPTOMS

SO, WHAT IS PERSONALITY?

General definition of personality

Personality is a complex adaptive system

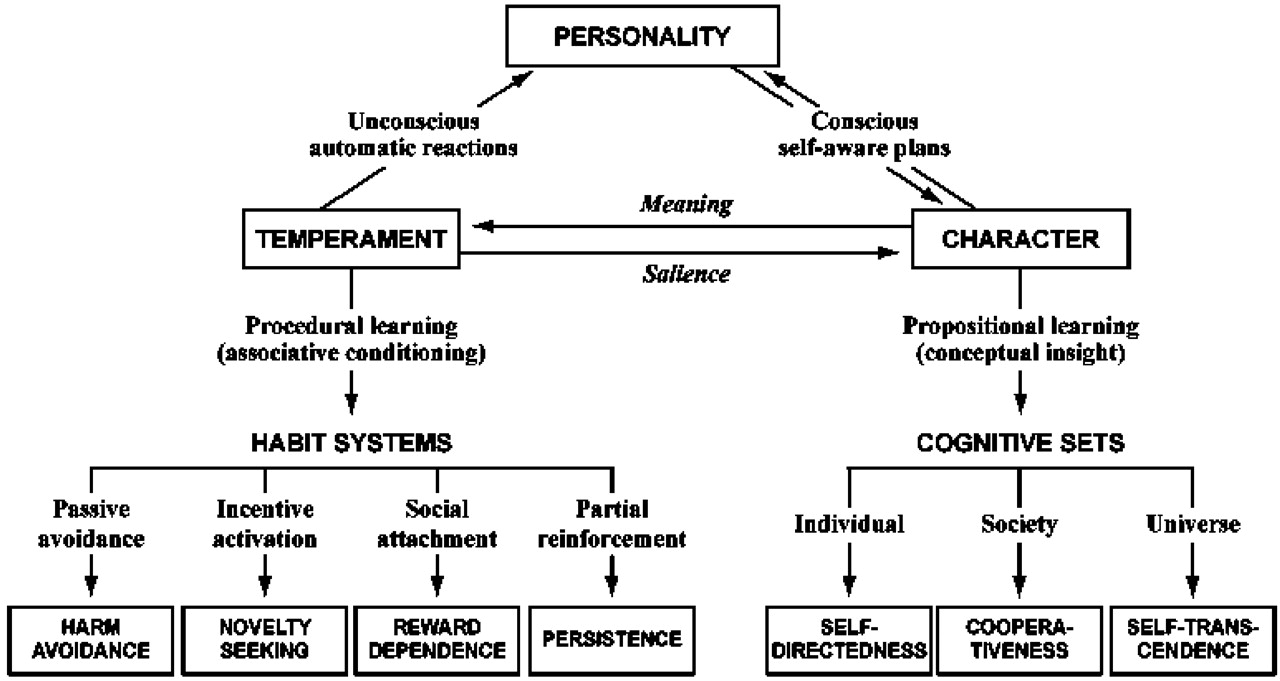

Distinguishing temperament and character

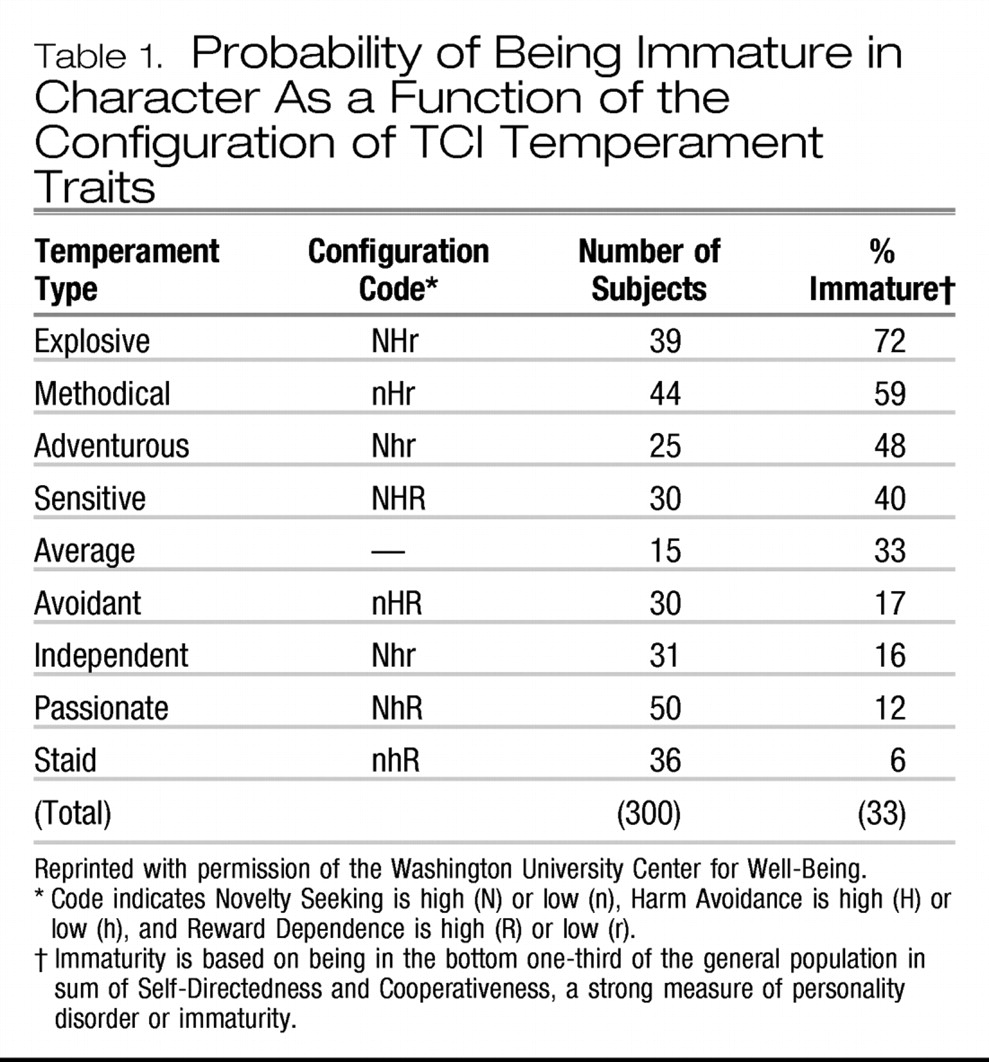

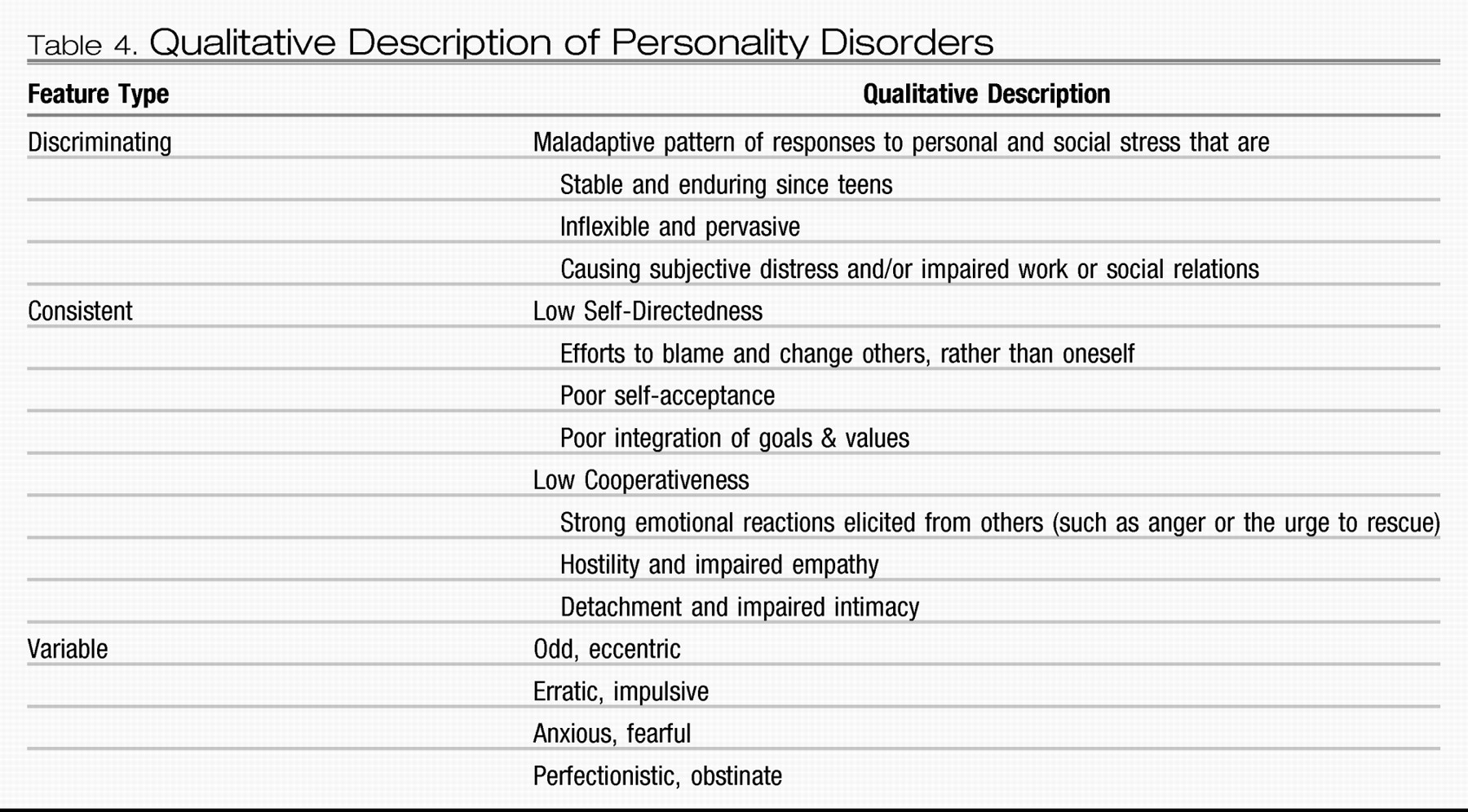

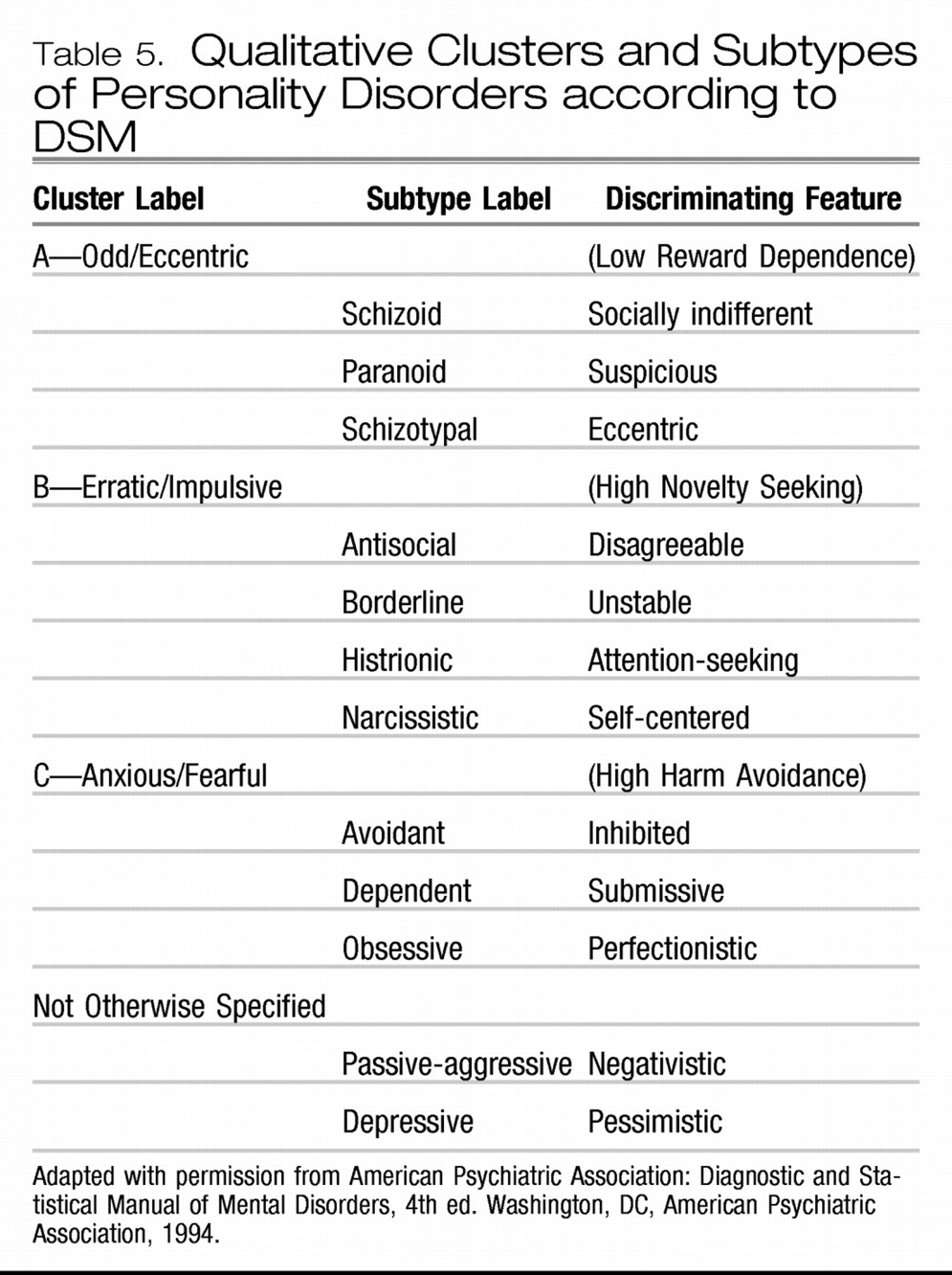

What is a personality disorder?

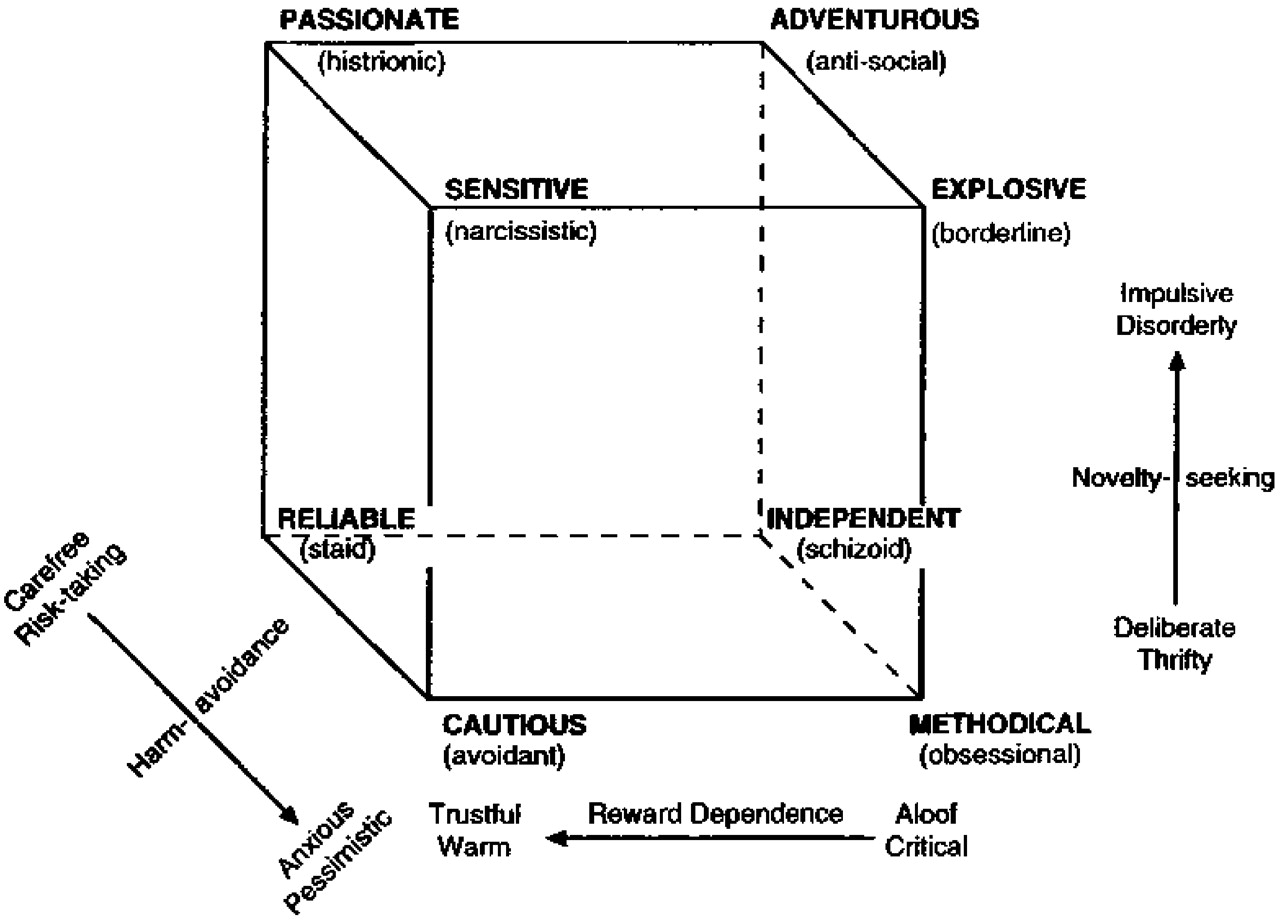

Describing temperaments and their interactions

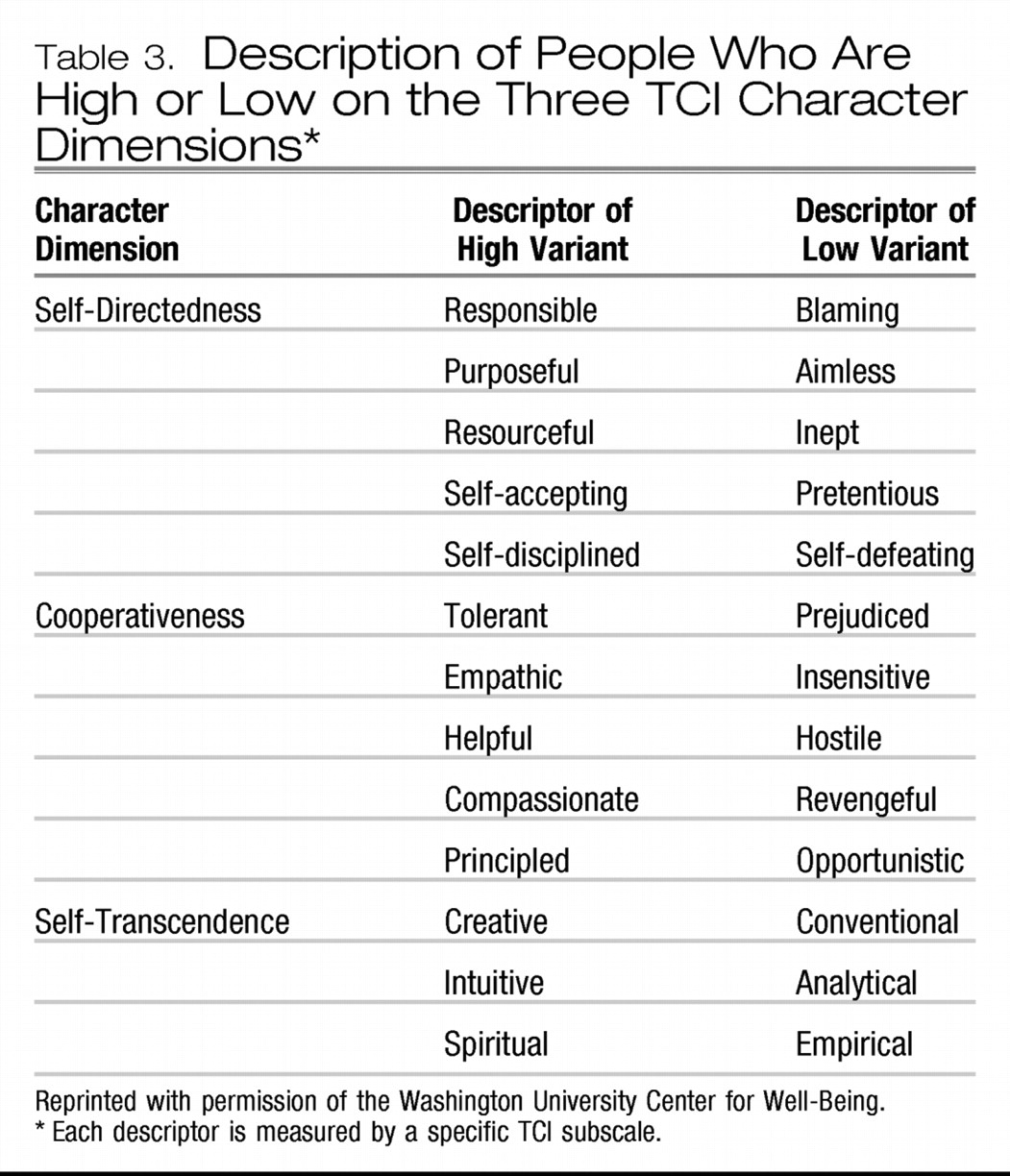

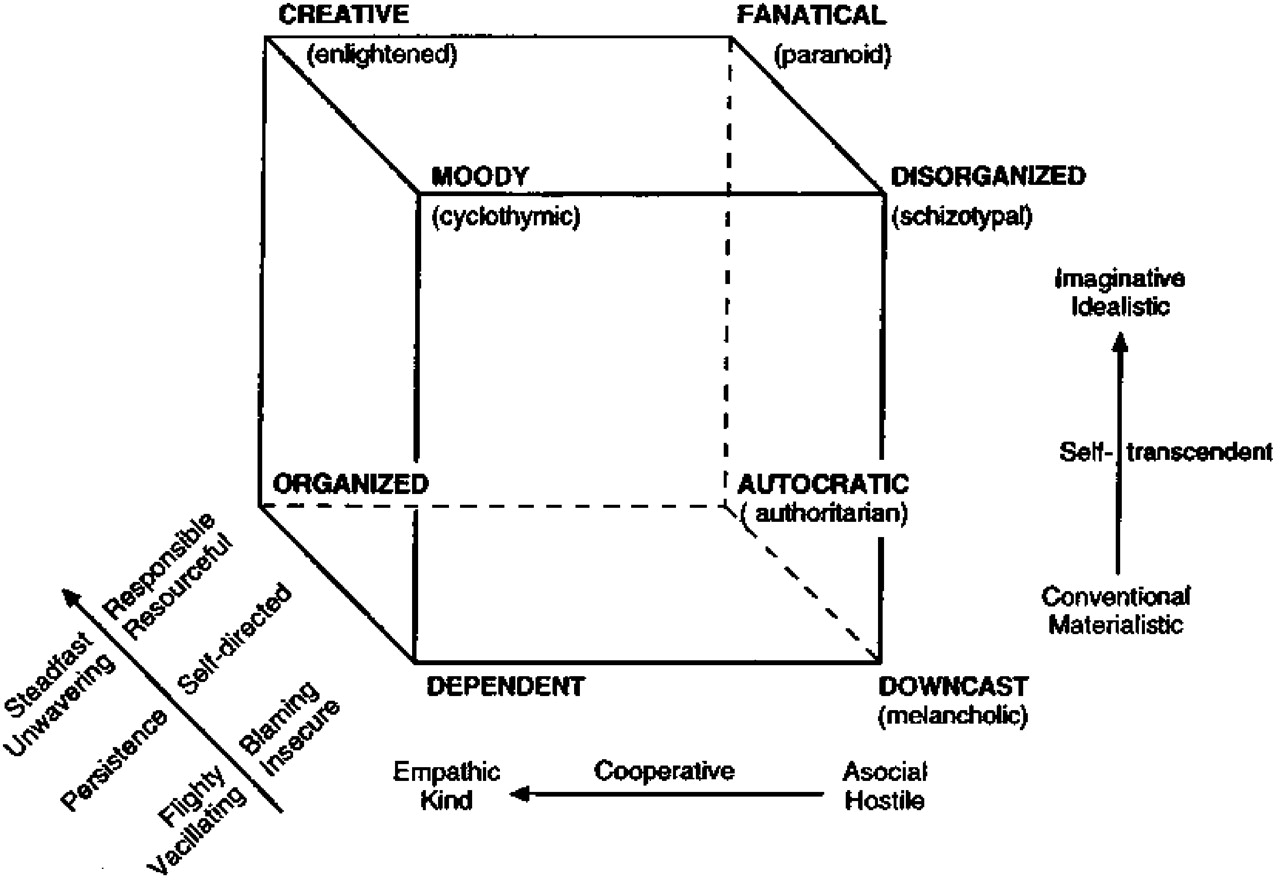

Describing character traits and their interactions

HOW DO WE MEASURE PERSONALITY?

Listening to personal narratives

Systematic observation and empathy

Recognition of the situational specificity

Assessing change over the lifespan

Clinical value of psychometric testing

Establishing a common language for dialogue

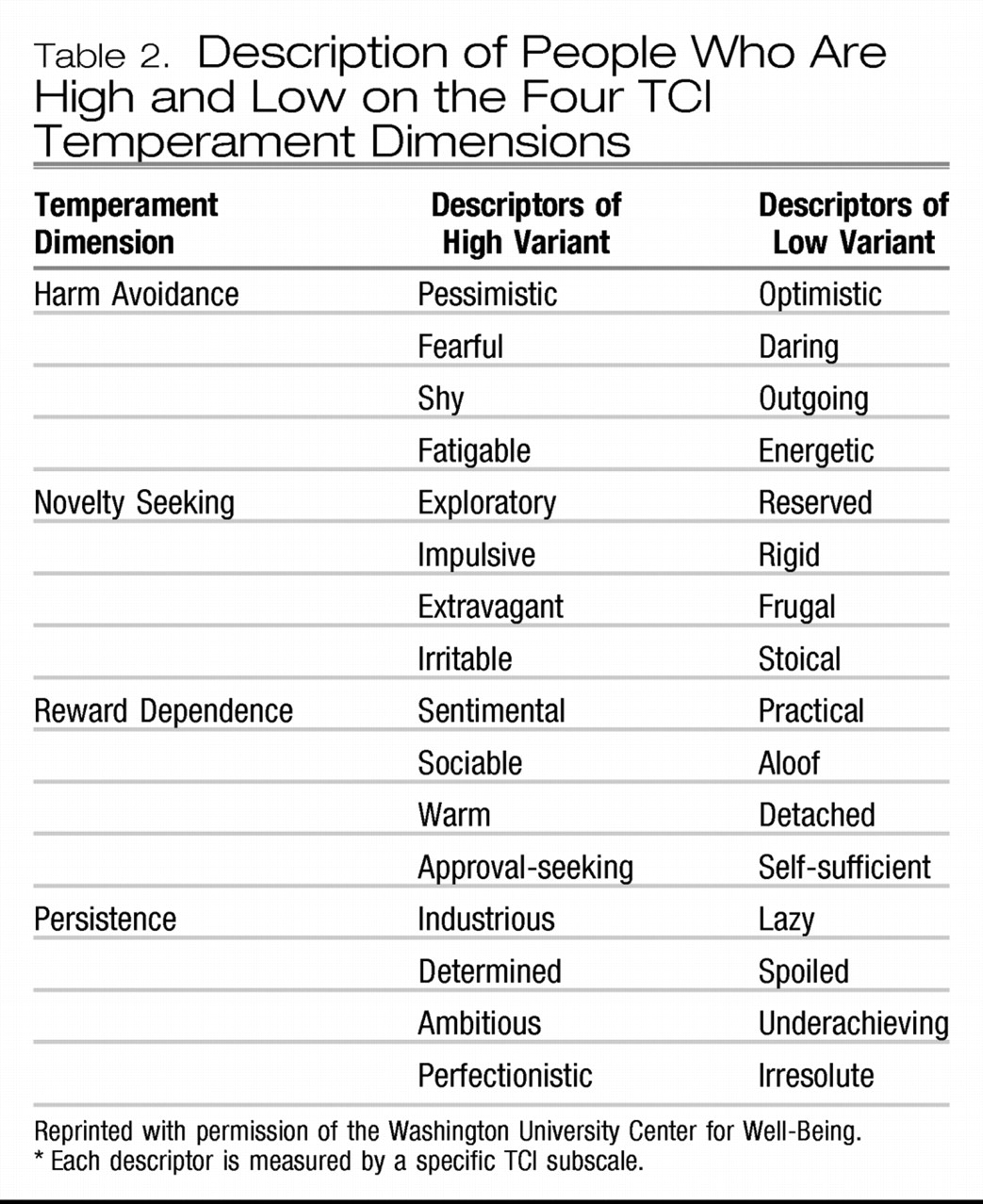

Now I'd like to talk to you about your results on the Temperament and Character Inventory. I'm sure you're familiar with lots of personality tests. I like this one particularly because I feel it offers a comprehensive and well-grounded system to understand how a personality is put together. It can provide us with a common language for discussing how your personality is related to your current problems. By better understanding who you are, you can set the stage for future changes to develop in a way that you can choose for yourself. The system divides personality into two components: temperament and character. Temperament describes your emotional style, which is partly unconscious or automatic reactions to things, like what makes you nervous or angry or excited. Temperament is moderately heritable. I think of it as your grandparents' personalities shining through you. Temperament is also fairly consistent over one's lifetime. Imagine someone who knew you in high school meeting you today. Something about you is still the same, something about how you function in the world or conduct yourself.In the TCI scoring, we are looking at percentile rankings: scores based on the distribution in a large population. Most people score close to the median or 50th percentile. People notice traits as prominent when they are in the top one-third (67% or higher) or bottom one-third (0%–33%). So if your scores are far from the 50th percentile, two things can be said about your personality: 1) that trait may be more prominent, for example, “she's the one who always is” (fearful, bored, seeking approval, etc.) and 2) that prominent factor may be more problematic for you in your interactions. That same trait might be advantageous to you in some other circumstances. Extreme scores can have both advantages and disadvantages, depending on the situation and your goals, so they are not necessarily “good” or “bad.” We will review the role all these traits play in your life in different situations. We'll explore ways to help modify whatever is causing you trouble in your day-to-day life. The encouraging news is that by understanding your personality you can shape how you develop and live your life in the future. No matter how our parents reared us or what childhood experiences we have had, we always have the opportunity to cultivate our own growth, by ourselves or in therapy as you are now.If we can't nurture our personality development, then we will have the “depressive” outlook of low Self-Directedness, low Cooperativeness, and low Self-Transcendence. People low in Self-Directedness blame their problems on other people or circumstances, lack clear goals in life, and feel powerless; their life seems hard to them. People who are low in Cooperativeness are prejudiced, hostile, and revengeful; they feel that people are mean and unfair. People who are low in Self-Transcendence feel little connection to anything beyond their own immediate experience; they may have difficulty appreciating and enjoying the beauty of nature or of a spiritual connection to others or even God. The depressive character configuration is evident in a person who grumbles: “Life is hard, people are mean, and then you die—so what's the value of living?” [The patient's scores on each character dimension should be discussed with give-and-take about whether the self-reported description corresponds to the patient's understanding of himself or herself, with give-and-take about its meaning and implication.]On the other hand, if we are able to promote our character development, then, we'll have a more creative or “enlightened” outlook of high Self-Directedness, high Cooperativeness, and high Self-Transcendence. Self-directed people are responsible, purposeful, and resourceful. Cooperative people are tolerant, helpful, and forgiving. Self-transcendent people are intuitive, joyful, and spiritual. The creative character configuration is expressed by feelings of acceptance, generativity, and integrity. When people are dying with integrity, even if it's “too young,” they are able to say that “I've done what I could, loved and been loved, and now I'm ready for whatever's next.”As a human being with intelligence and freedom of will, you are both free and responsible to make the choices that allow you to experience satisfaction and meaning in your life. The fact is that you are actively making choices all the time, so you might as well begin to understand what choices you really want to make—what you really value and find gives lasting satisfaction. Then we can explore together how to create congruence between what choices you make today and what you want to have happen in the next chapter of your life. You are always writing that next chapter in your life journey. You can cultivate goals and values in your character that will allow you to better regulate your emotional drives (that is, what is measured by the temperament traits in this test) and thereby bring more satisfaction and well-being into your life. Once you understand yourself better, you'll find that it is really possible to become healthier and happier, even if that seems impossible to you now.Temperament measures your emotional drives. The first dimension of temperament is called Harm Avoidance, a measure of anxiety proneness. [Discuss the patient's Harm Avoidance score.] It is higher in people who are prone to depression and anxiety and higher when they are in the throes of anxiety or depression. You can see here the related factors of anticipatory worry, fear of uncertainty, shyness, and fatigability. I can give you some tools to help you move away from being so susceptible to anxiety [here I might tell them of some cognitive behavior tools/paradigms to address the anxious mind], but we need to recognize that, if you are high in Harm Avoidance now, were we to meet 10 years from now, it is likely you'll be worrying about something!The second factor is Novelty Seeking. This is a measure of incentive activation, the appeal of the novel and the new, and also an indicator of anger proneness. [Discuss the patient's Novelty Seeking score.] The lower it is, the more structured and regimented you are and the more you prefer the usual routine. The higher it is, the more you demonstrate exploratory excitability, impulsiveness, extravagance, and disorderliness. The higher your Novelty Seeking, the more open you may be to taking a new route home from work today. Imagine I've given you plane tickets to an exotic location. If you have low Novelty Seeking, you'll prefer everything to be more structured and planned; maybe you'd want me to have provided tickets to the museum for Thursday, reservations at the best restaurant in town for Friday, seats for the ballgame Saturday…. If your Novelty Seeking is high, you might tell me “It will be fun to explore the city on my own and be surprised by all that's new or unexpected.” [People often laugh in agreement and begin to relax when they recognize how well they've been described, accepted, and understood by an ally!]The third factor is Reward Dependence. I think of this as social currency. It is a measure of sentimentality, attachment, and dependence (although I need to let you know that these words have been given a meaning different from our conventional definitions). [Discuss the patient's Reward Dependence.] Imagine a dinner party that you've hosted. You're in the kitchen with the dessert, which you've made. The person with Low Reward dependence knows that he's used an excellent recipe, superb ingredients. It's a great dessert—he could sit and admire it—in the kitchen, all night long. The person with higher Reward Dependence needs to go out and serve a portion, or even seconds, to everyone, and have someone ask for the recipe. “Did you see? Mrs. Jones, she never likes sweets! And she's asked me for my recipe!” The value of the experience is really the same in both instances, except in the first case the value is derived from the individual himself and in the second, the value comes from the social interactions. In other words, highly reward-dependent people need approval from others. As a result, they often have a hard time saying no when asked for favors.The fourth temperament is Persistence. This is a measure of how we deal in a situation that offers only intermittent success. It measures determination, ambition, and perfectionism. [Discuss the patient's Persistence score.] Think of the laboratory animal in the cage: Press the Lever. Get a Treat. Press the Lever. Get a Treat. Press the Lever. – – – No Treat (?!) Now the animal needs to decide how to apply its efforts. High Persistence would have the animal persevere in pressing the lever to obtain treats, even though there is no guarantee of any additional treats. An animal with lower Persistence might decide to put energy into playing on the exercise wheel, which offers more immediate and ensured feedback for the effort invested. Persistence might be considered an indicator of prudence, how one chooses to apply the resources one has. Consider the “Hold 'Em” and “Fold 'Em” scenarios at a poker table. Only that particular individual knows what cards she has in hand; only that particular individual can read how the other players seem to be viewing their cards. Only that particular individual can vote to put her resources in (Hold 'Em) or pull out of the hand (Fold 'Em). Persistence is a measure of the impact of obstacles in a path. Let's say you are planning to meet a friend in the afternoon for coffee. Stepping outside, you realize your vehicle has a flat tire. The person with low Persistence loses heart, is dismayed that his day is ruined, his week is ruined, and his friendship will be irreparably damaged. The person with high Persistence recognizes that he would very much like to visit with the friend, only the meeting will be later than originally planned. You can see how Persistence is a measure of ambition, because we will enjoy few successes if we don't stick with anything to see it to fruition. One can also appreciate how plain old tenacity is no assurance of success either and may be an unwise application of valuable resources. The example that comes to mind is an unrequited dating relationship: one person is very much invested in pursuit… but no amount of attention, messages, or small or large gestures will win a disinterested heart.

IMPLICATIONS FOR TREATMENT

The person-centered treatment process

Use of personality in medication management

One can read about an illness, and know something of it, but to live it is to truly know it. The highly individual nature of depression is fascinating. It can be caused, complicated, and evidenced by an astounding number of diverse factors. Antidepressants only treat the symptoms, and not the causes. I believe, like denial, they serve a short-term purpose.

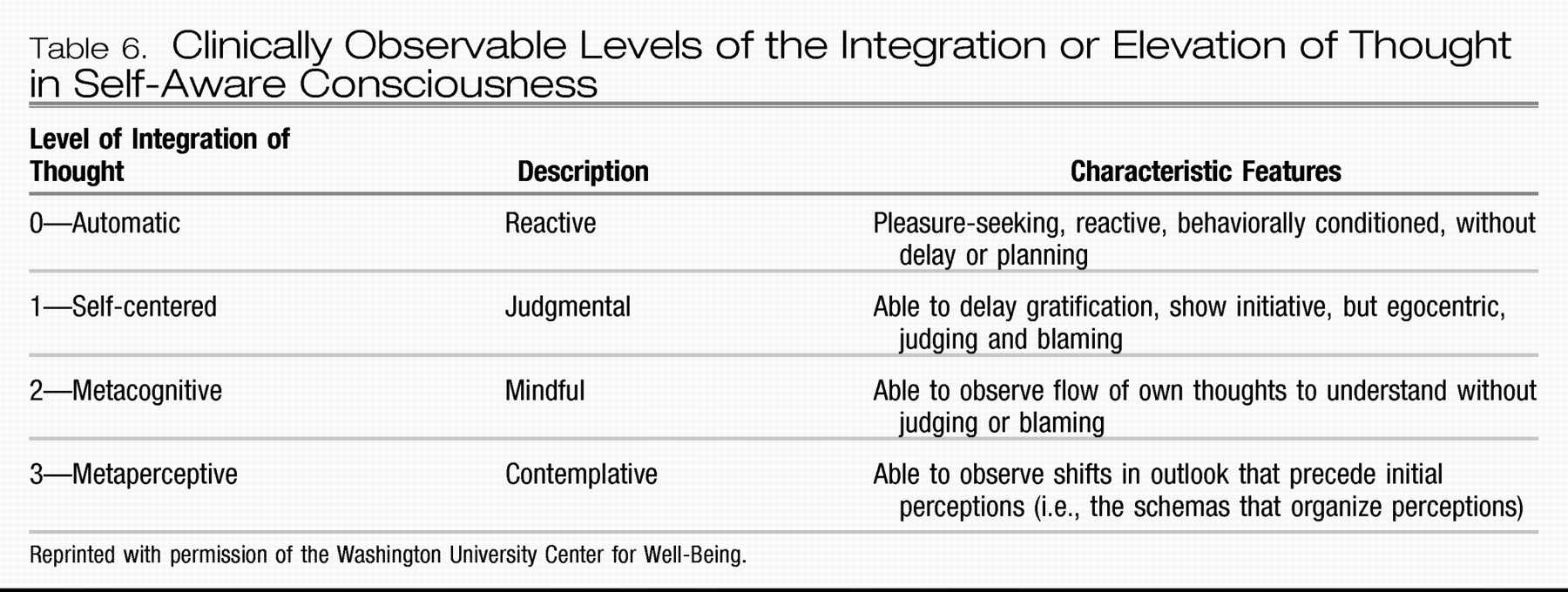

Awakening a perspective of well-being

QUESTIONS AND CONTROVERSY

SUMMARY

REFERENCES

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

History

Authors

Funding Information

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Citations

Export Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.

For more information or tips please see 'Downloading to a citation manager' in the Help menu.

View Options

View options

PDF/EPUB

View PDF/EPUBGet Access

Login options

Already a subscriber? Access your subscription through your login credentials or your institution for full access to this article.

Personal login Institutional Login Open Athens loginNot a subscriber?

PsychiatryOnline subscription options offer access to the DSM-5-TR® library, books, journals, CME, and patient resources. This all-in-one virtual library provides psychiatrists and mental health professionals with key resources for diagnosis, treatment, research, and professional development.

Need more help? PsychiatryOnline Customer Service may be reached by emailing [email protected] or by calling 800-368-5777 (in the U.S.) or 703-907-7322 (outside the U.S.).