Over the past decade, a wide range of reviews, reports, and practice guidelines addressing smoking cessation have been developed (

2,

4,

25–

30). The consistent recommendations emerging from these reports comprise a standard of care for the screening and treatment of nicotine dependence (

31,

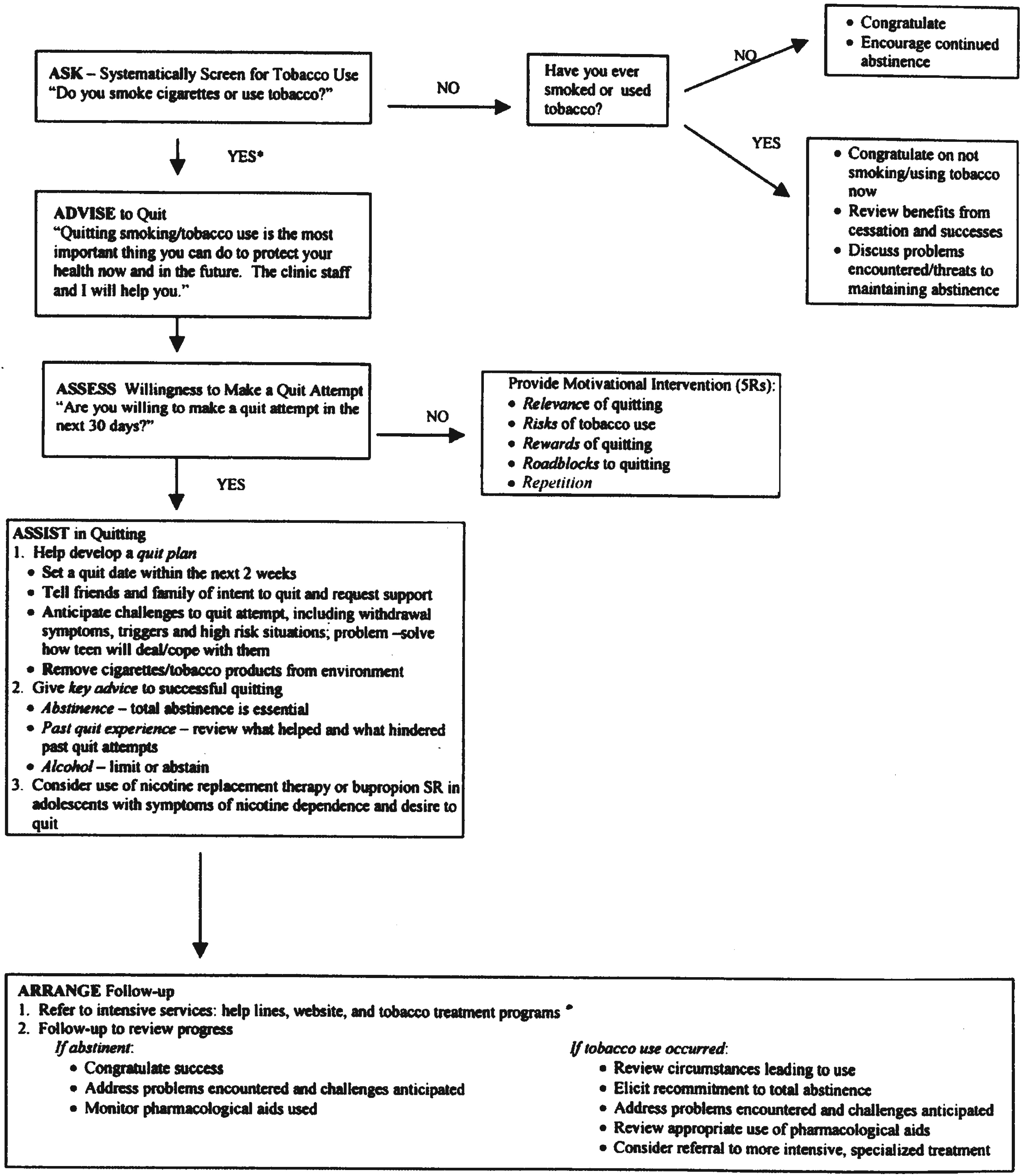

32). Among protocols, the 5 A's has been particularly influential; it stands on a robust evidence-based platform, as well as being simple, comprehensive, and easy to use (

Figure 1). For practice settings in which treatment interventions are not feasible, the AAR model (Ask, Advise, and Refer to a national quit-line) has been recommended as an alternative (

33). The central components common to clinical smoking cessation interventions are as follows.

Assessment

The first phase of any clinical smoking intervention is assessment. Assessment involves screening for tobacco use, determining the current level of nicotine dependence, assessing the current motivation to stop smoking, and evaluating patient-specific factors that affect selection of an intervention. Merely having a screening intervention in place is associated with increased odds of smoking cessation (

4).

Establishing a diagnosis of nicotine dependence can be done with a clinical interview eliciting DSM-IV-TR dependence criteria. Inquiring about “time to first cigarette” is particularly effective for determining severity of dependence (

34): in the morning, when nicotine has been largely eliminated from circulation during sleep, nicotinic cholinergic receptors are in a sensitized state, and highly dependent smokers experience intense craving (

35). The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence is a brief clinician-administered questionnaire with excellent reliability and validity for measuring nicotine dependence (

34). When definitive confirmation is sought, biological indicators such as breath carbon monoxide can detect smoking within the last few hours, and urine cotinine levels can detect smoking within the past 7 days (

30,

36).

Assessment of motivation to stop smoking can be done using the “stages of change” model. This model posits that for any volitional lifestyle modification, individuals go through phases of

precontemplation,

contemplation,

preparation,

action, and

maintenance (

37). Movement through these phases need not be linear; however, frequently assessing where on the continuum a patient lies facilitates a determination of how best to encourage and support him or her. For patients who are preparing to stop smoking, a targeted assessment of key areas facilitates individualization of smoking cessation interventions. These areas include experiences with past quit attempts, severity of nicotine dependence, vulnerability to withdrawal symptoms, social resources, cultural orientation, medical comorbidities, weight gain propensity, pregnancy status, potential drug interactions, and stability of any mental illness (

4,

30).

Education

Education is a central component of all smoking cessation interventions. Many smokers are misinformed about the health risks of nicotine and the safety and efficacy of smoking cessation interventions. For instance, in a study examining what subjects know about nicotine replacement, it was found that as many as half of smokers believed that nicotine itself was the cause of cancer (

38). Such beliefs may undermine adherence with nicotine replacement therapy. Likewise, whereas many smokers view cessation as overcoming the period of acute withdrawal, education about long-term relapse risk may facilitate engagement in an ongoing follow-up plan.

Smokers should understand that withdrawal symptoms peak in the first 1–2 weeks but may persist for months. Even a single puff increases the risk of relapse. In addition to reviewing common symptoms of withdrawal, clinicians should explore patient-specific obstacles to smoking cessation. Weight gain is a frequent concern. Nicotine suppresses appetite and increases metabolism (

39) such that on average, smokers gain 3–5 kg within the first 6 months of smoking cessation (

4,

40). Both behavioral weight reduction interventions and smoking cessation medications prevent weight gain while being used; however, neither has been shown to generate enduring reductions in weight (

41).

Results of studies regarding whether, in the absence of clinician assistance, the provision of self-help information alone reduces smoking have been inconsistent (

42). Provision of educational materials is always advisable, but there is a need for the development of more effective self-help materials and strategies.

Counseling

Counseling for smoking cessation should always occur within a supportive framework. The core features of any counseling approach include

1.

establishing a therapeutic alliance and treatment frame,

4.

eliciting patient preferences about treatment,

5.

determining timing and quit date,

6.

deciding method for smoking cessation,

8.

monitoring and follow-up (

30).

A number of distinct psychotherapies have been manualized and studied for smoking cessation. These include contingency management, relaxation techniques, aversive therapy, cue exposure, problem solving, skills training, motivation enhancement, supportive psychotherapy, and interventions to increase social support in the smoker's environment (

4). Studies of these approaches have rarely compared them with each other, making it difficult to infer superiority of any treatment over another. By and large, the therapies can be grouped into three overlapping classifications. Behavioral approaches focus on changing behaviors through techniques such as conditioning, desensitization, behavior modification, and reinforcement. Cognitive approaches attempt to modify dysfunctional thoughts and beliefs that underlie maladaptive behaviors, as well as using skill acquisition to deal with triggers and cravings. Supportive approaches emphasize patient-centered goal setting, empathy, establishment of intrinsic motivation, and problem solving. In practice, the above-stated counseling approaches may have substantial areas of overlap.

In the meta-analysis conducted for the U.S. Public Health Service (PHS) report, four therapy techniques provided significant increases in abstinence compared with untreated control conditions: practical counseling, intratreatment social support, extratreatment social support, and aversive smoking procedures (

29). The latter two treatments were dropped from PHS recommendations after analysis of subsequent Cochrane reviews (

4). The APA guideline recommends behavioral therapies as first-line treatment for smoking cessation because of the quantity of studies supporting their effectiveness (

30).

Cognitive behavior therapies may be particularly helpful in treating nicotine dependence among patients with co-occurring disorders (

30). Counseling can and should be integrated with medication management, because there are synergistic benefits (

4,

43). Group therapy doubles quit rates and is substantially more effective than self-help alone, although results of studies have been mixed with respect to how it compares with individual therapy (

44).

Telephone counseling, a widely available but underused resource, has also been shown to be effective. The U.S. national quit-line (1-800-QUIT NOW) uses a “proactive” model for intervention, whereby calls to smokers are initiated by cessation counselors based on a prearranged schedule (

45). A recent meta-analysis of 22 randomized controlled trials investigating computer-based programs found that such programs increased quit rates, but that effects dissipated 1 year out of treatment (

46).

Biological interventions

Three classes of medication are considered first-line for smoking cessation: nicotine replacement therapies (NRTs), of which there are five U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved agents, the atypical antidepressant bupropion, and the partial agonist varenicline. Each of these agents has been shown to be effective in multiple systematic meta-analyses (

4,

47–

52). Whereas the optimal duration of treatment with smoking cessation pharmacotherapies has not been determined, most medications are used for periods ranging from 6 weeks to 6 months, and studies generally reveal a dose-response relationship between duration of treatment and long-term abstinence (

54–

56).

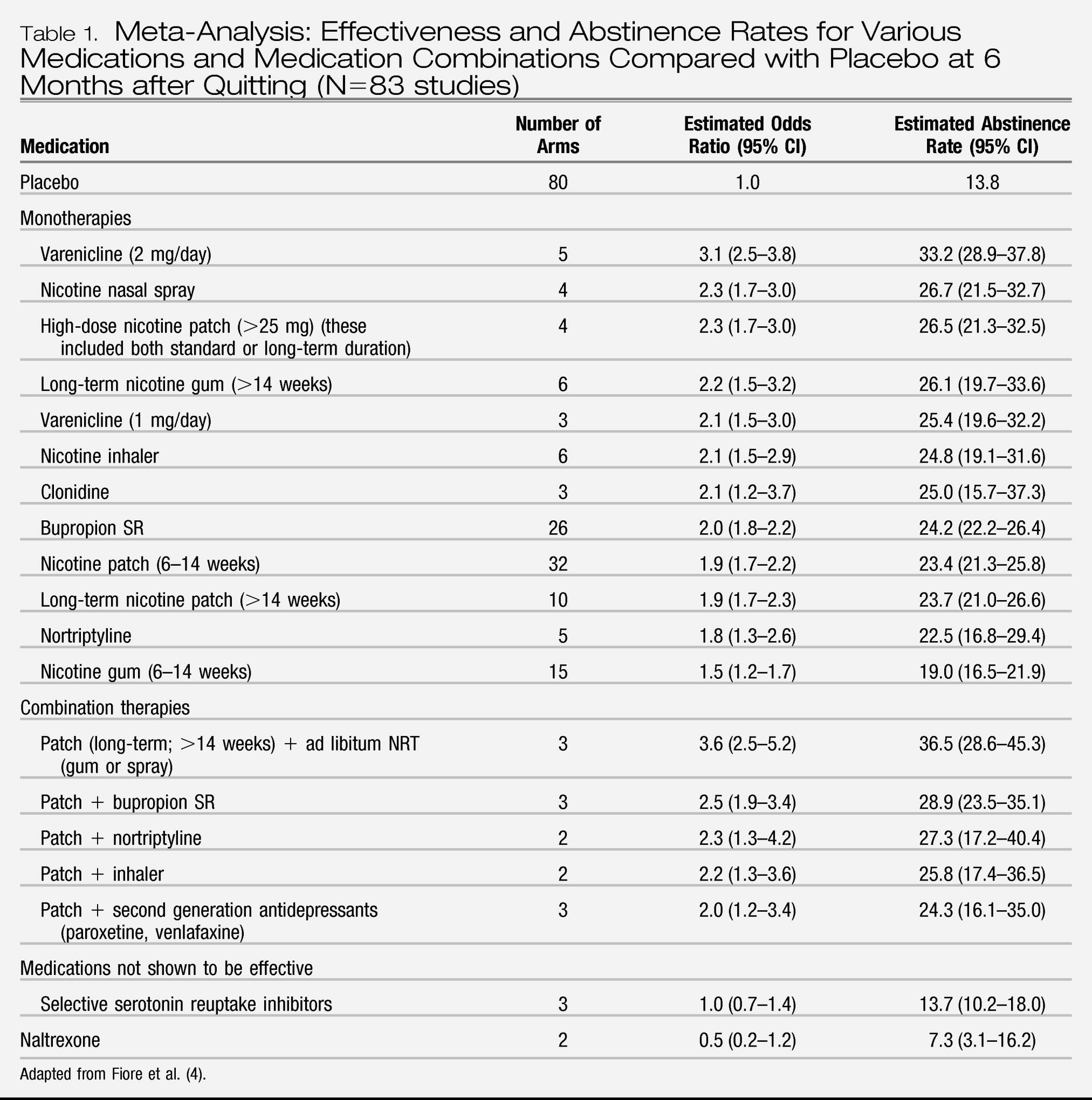

Table 1 summarizes the PHS meta-analyses on 6-month quit rates with various cessation medications compared with placebo.

NRTs function by alleviating nicotine withdrawal symptoms, as well as by interfering with the behavioral ritual of smoking. Short-acting agents, such as gum, inhaler, spray, or lozenge, simulate the periodic burst of nicotine associated with smoking. The nicotine patch produces much more constant nicotine levels, and its ease of administration facilitates high adherence. The combination of the patch with a short-acting agent (to attenuate breakthrough craving) is more effective than the patch alone (

56). NRTs should be initiated on the quit date and titrated upward to alleviate subjective craving, as higher doses have been associated with lower relapse (

57).

There are few contraindications to use of NRTs. Pregnancy is discussed below. Light smokers (<10 cigarettes/day) and adolescents may benefit from reductions in the dosing of NRTs, although overall, the evidence base for NRTs in this population is less strong, and an individualized risk-benefit analysis must be undertaken (

4,

58). Given the mild stimulant characteristics of nicotine, patients with unstable cardiac disease should also be carefully evaluated before initiation (

59). Most recently, electronic cigarettes have been developed to better mimic the pharmacokinetics of smoking; however, this method of nicotine administration has not been well studied (

60), and the FDA has issued warnings pertaining to safety and quality control (

61).

Sustained release bupropion, a dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, has been shown to double the likelihood of smoking cessation (

50). Bupropion can be used in combination with an NRT, as the two appear to have additive benefits (

62). Bupropion should be started 7 days before the quit date to enable stabilization of serum levels. Given the effectiveness of bupropion for depression, it is a reasonable choice for patients with nicotine dependence in the setting of depression. The dose-dependent effect of bupropion on seizure risk poses a relative contraindication among patients with conditions that lower seizure threshold.

Varenicline, a partial nicotinic cholinergic receptor agonist, is thought to work by blocking the reinforcing effects from smoking, while stimulating sufficient release of dopamine to reduce craving and withdrawal. Varenicline has consistently demonstrated efficacy in clinical trials, both in comparison with placebo and with the first-line agents nicotine patch and bupropion (

48). Notably, postmarketing surveillance data has revealed a correlation between varenicline and neuropsychiatric decompensation (

63). Although this correlation has not yet been demonstrated in randomized controlled trials, a black box warning has been placed, and it is prudent to ensure that psychiatric disorders are stabilized before initiation of varenicline and to monitor patients closely throughout treatment. As with bupropion, varenicline titration should be started 1 week before the quit date such that serum levels are sufficient before nicotine withdrawal develops. As with all smoking cessation pharmacotherapies, dose modification may be indicated to achieve an appropriate balance between tolerability and reduction in nicotine craving.

The tricyclic antidepressant nortriptyline appears to have efficacy similar to that of NRTs; however, the side effect profile of nortriptyline and its toxicity in overdose relegate it to second-line status (

4). Other antidepressants, such as the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, have not been found to increase smoking cessation (

50). Clonidine, a centrally acting α2 receptor agonist, has shown some efficacy compared with placebo. However, its relatively low efficacy and frequent side effects (dry mouth and sedation) limit its role in the treatment of smoking, primarily for individuals in whom multiple other pharmacotherapies have failed (

49).

Complementary interventions

A number of complementary alternative therapies have been used for smoking cessation, including acupuncture, acupressure, relaxation, hypnotherapy, yoga therapy, exercise therapy, laser therapy, and electrostimulation. There is a dearth of methodologically robust research on these interventions. Acupuncture is probably the best studied, and thus far meta-analyses have not revealed persisting benefits compared with placebo (sham acupuncture) (

64,

65). However, neither have existing studies shown any harm. Patients should be informed about the state of the evidence, but not discouraged from pursuing alternative therapies for smoking cessation (

66). Those who perceive or experience benefits from alternative therapies should receive encouragement and support (

4).