Suicide-related morbidity and mortality among psychiatric patients are ongoing concerns in providing good patient care (

1,

2). The vast majority of individuals who experience such morbidity or mortality will have an underlying psychiatric illness (

1,

3–

14). Population-based evidence has consistently demonstrated that fatal and nonfatal suicidal behaviors can be associated with mood disorders, psychotic disorders, substance use disorders, anxiety disorders, conduct disorder, and antisocial and borderline personality disorders (

4,

5,

13–

27). Psychiatric disorders represent potentially modifiable risk factors, and their identification and appropriate treatment are central components of efforts to reduce risk for suicide (

3,

7,

28).

Suicide fatalities are the 11th leading cause of death in the United States, accounting for 1.4% of all deaths (

29). In 2007, the most recent year for which final mortality data are available, the 34,598 suicide deaths in the United States represented a rate of 11.3 deaths per 100,000 individuals (

29). The 12-month prevalence of nonfatal suicidal self-injuries among U.S. adults ranges from 0.2% to 0.6% (

4,

5,

14–

15).

The national burden of injury associated with fatal and nonfatal suicidal behaviors is large and includes hospitalization, emergency department visits, reported events, unreported events that are not medically treated, and suicide mortality. The overall burden translates into nontrivial economic and societal costs, with 376,306 individuals treated in emergency departments and 163,489 hospitalized in 2008 (

30), direct costs estimated to be approximately $68 million (

31), indirect costs estimated to be $11.8 billion (

28), and devastating emotional consequences for families and friends of decedents.

Suicidal behaviors exist along a continuum from fleeting thoughts about suicide at one end to ending one's life at the other end (

28). The fundamental features that define suicidal thoughts and behaviors and that distinguish suicidal from nonsuicidal thoughts and behaviors are 1) the act must be self-inflicted, 2) the act must be intentional, and 3) the objective is death (

28). A useful nomenclature proposed by O'Carroll and colleagues (

2,

32) that reflects these fundamental features and defines a gradation in the continuum of suicide-related behaviors includes the following:

•.

Suicide: Self-inflicted death with explicit or implicit evidence that the person intended to die

•.

Suicide attempt: Self-injurious behavior with a nonfatal outcome accompanied by explicit or implicit evidence that the person intended to die

•.

Aborted suicide attempt: Potentially self-injurious behavior with explicit or implicit evidence that the person intended to die but stopped the attempt before physical damage occurred

•.

Suicidal ideation: Thought of serving as the agent of one's own death; seriousness may vary depending on the specificity of suicidal plans and the degree of suicidal intent

•.

Suicidal intent: Subjective expectation and desire for a self-destructive act to end in death

•.

Lethality of suicidal behavior: Objective danger to life associated with a suicide method or action. Note that lethality is distinct from, and may not always coincide with, an individual's expectation of what is medically dangerous.

•.

Deliberate self-harm: Willful self-inflicting of painful, destructive, or injurious acts without intent to die

More recent nomenclatures building on the works by O'Carroll and colleagues include the Institute of Medicine proposed nomenclature in their review

Reducing Suicide: A National Imperative (

28), and the Columbia Classification Algorithm of Suicide Assessment (C-CASA) (

33).

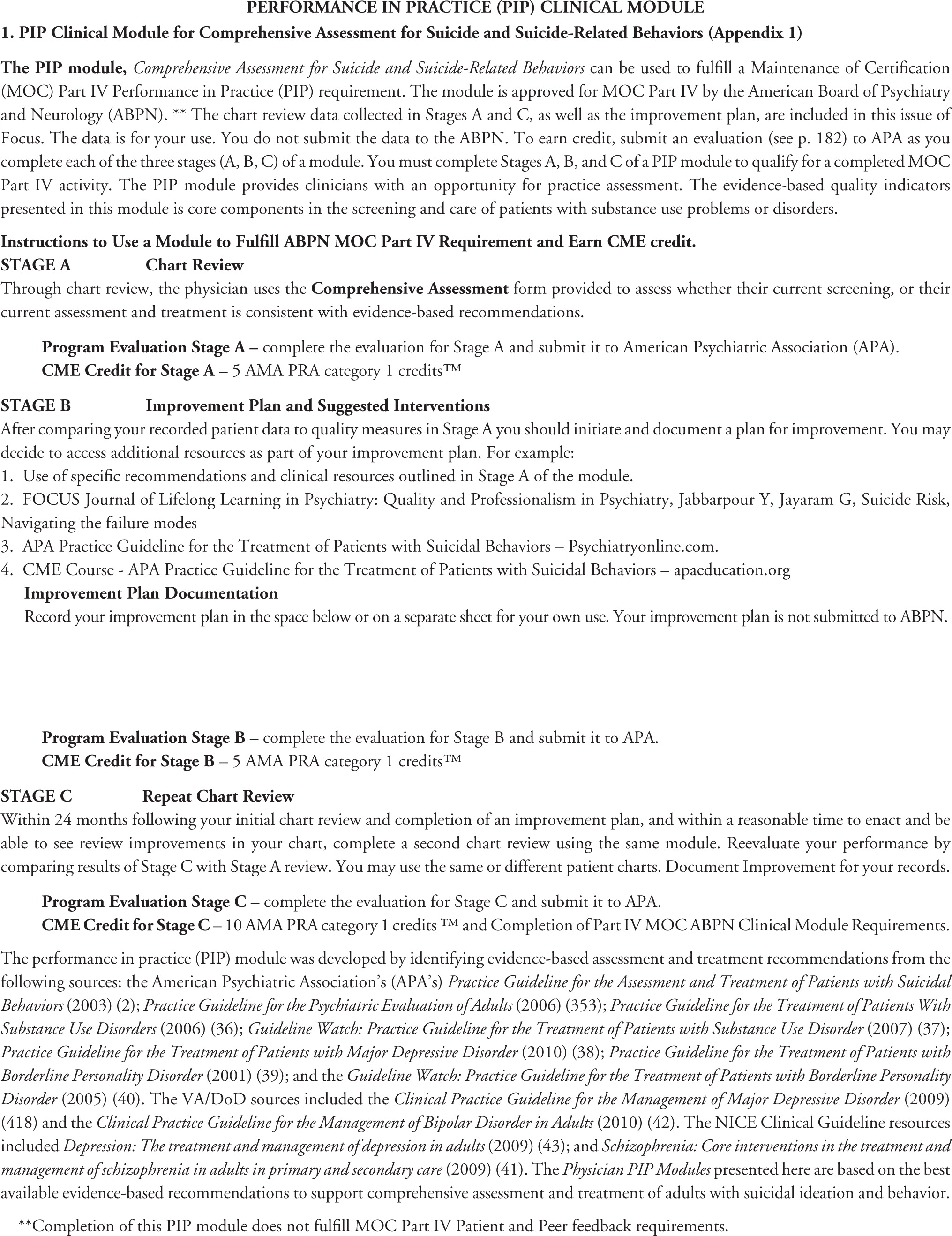

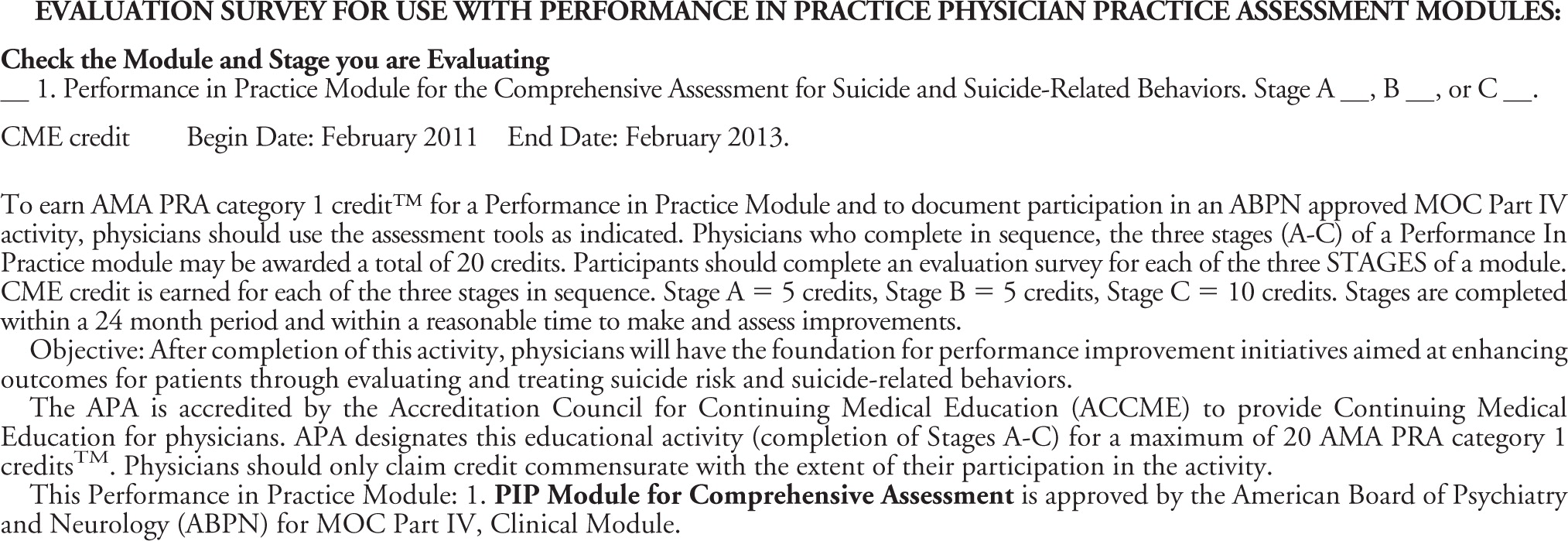

MAINTENANCE OF CERTIFICATION: PERFORMANCE IN PRACTICE (PIP) PHYSICIAN PRACTICE ASSESSMENT REQUIREMENTS

By 2014, the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) and the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology (ABPN) plan to implement multifaceted

Maintenance of Certification (MOC) requirements to enhance quality of patient care and assess competence of physicians over time (

34). The MOC process will include a practice assessment component, requiring physicians to compare their care for five or more patients “with published best practices, practice guidelines or peer-based standards of care.” Based on the results of this practice assessment, physicians are then asked to develop a practice improvement plan to enhance effectiveness and efficiency in delivery of clinical care and reevaluate their practice within 24 months after the initial evaluation (

34).

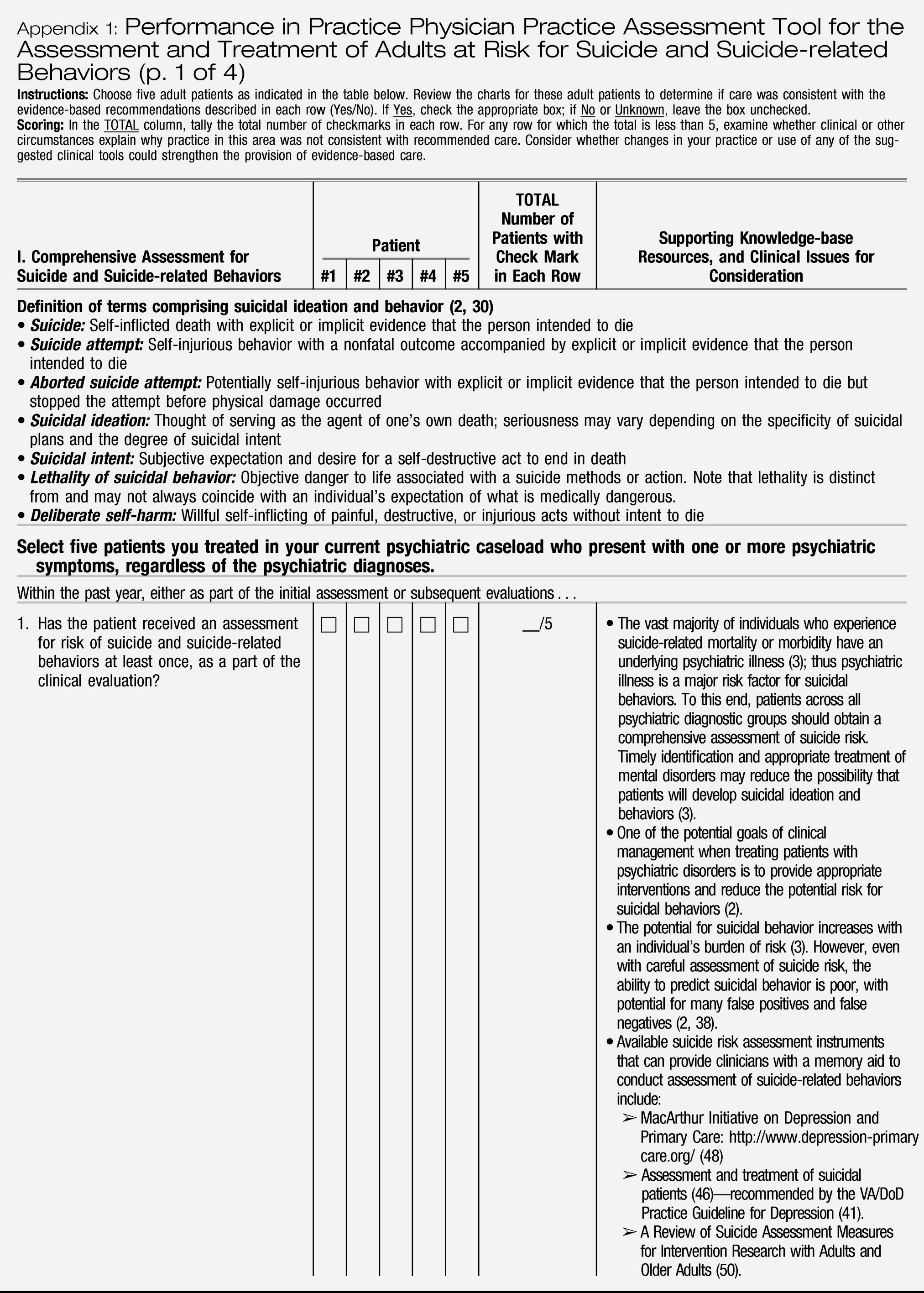

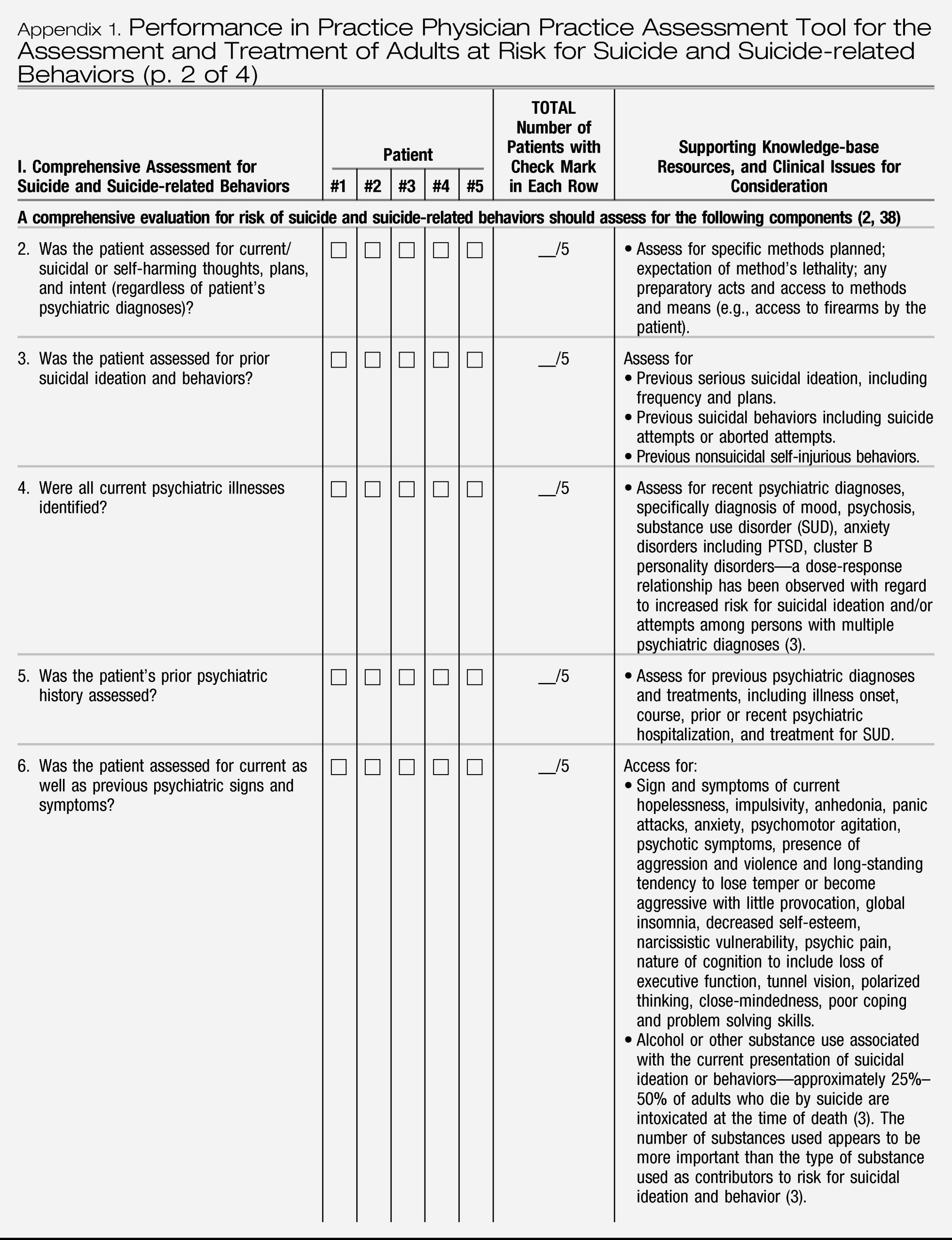

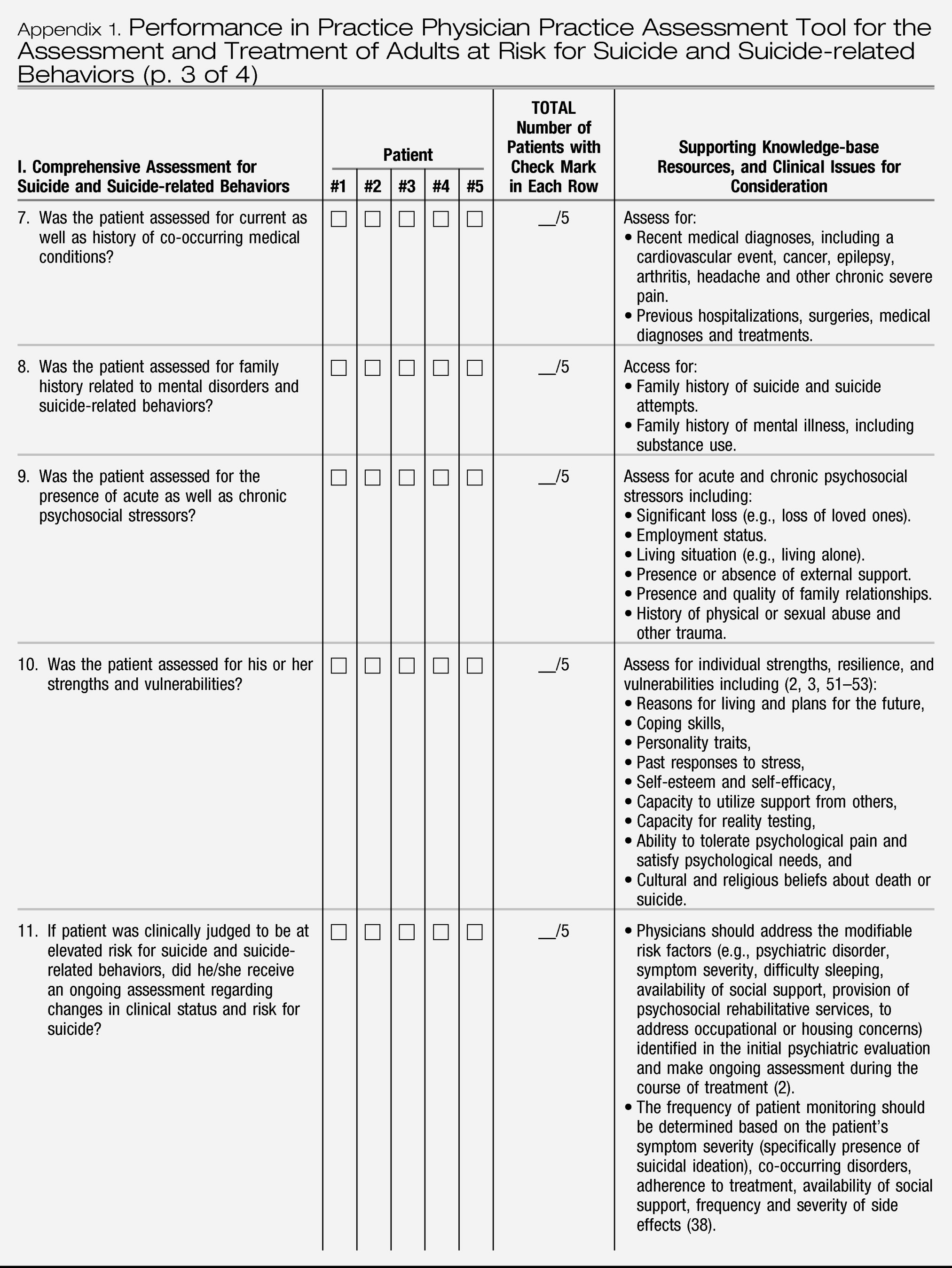

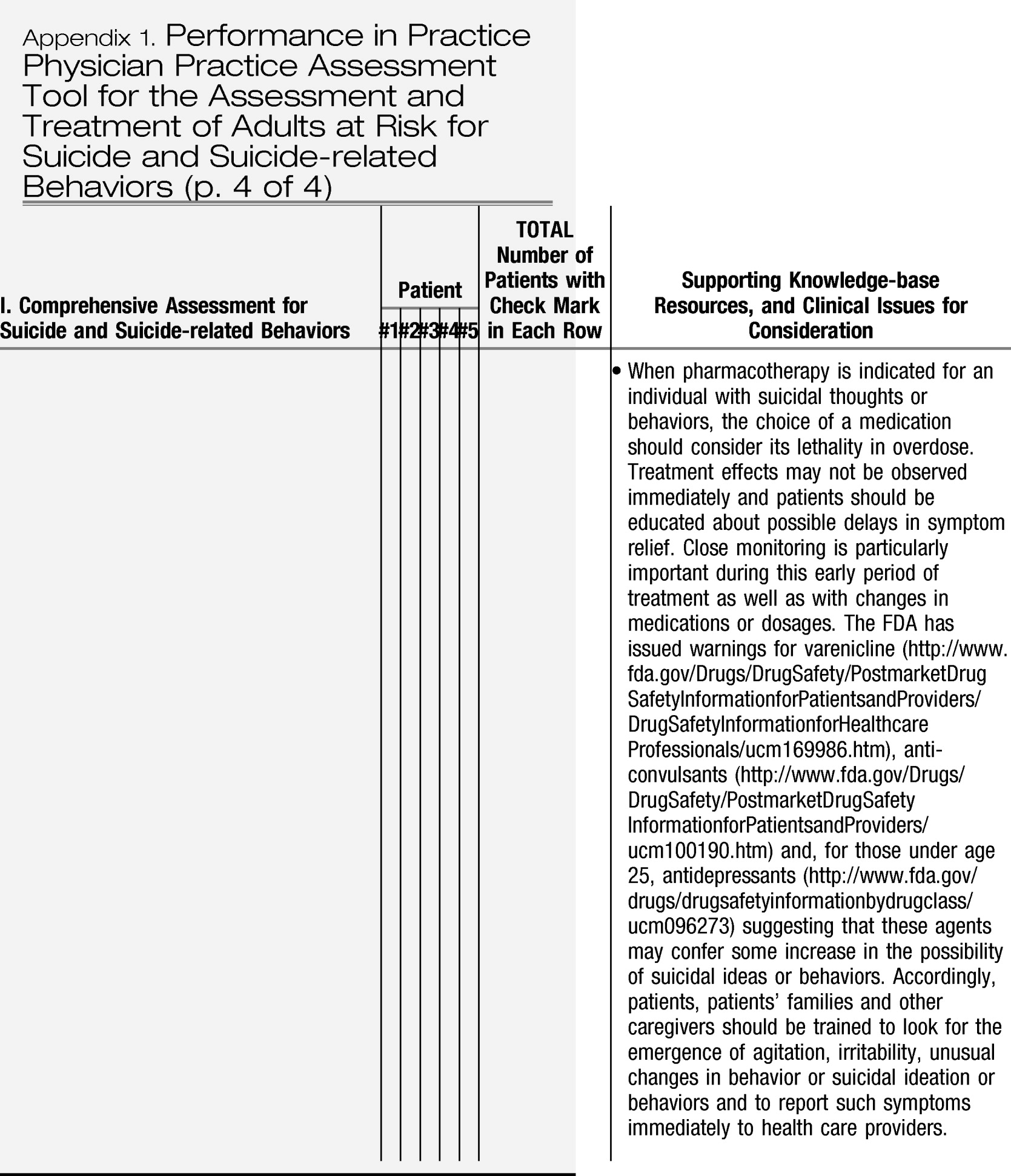

Suicide risk assessment is one of the core components of a comprehensive psychiatric evaluation (

35). Given the potential for suicidal ideation and behavior across the spectrum of psychiatric disorders, timely identification and appropriate treatment of mental disorders, which are considered potentially modifiable risk factors, may reduce the probability of patients developing suicidal ideation and behaviors (

3). Moreover, several evidence-based treatments are currently available to target suicide-related behaviors. The

Performance in Practice Physician Practice Assessment Tool for the Assessment and Treatment of Adults at Risk for Suicide and Suicide-related Behaviors presented in

Appendix 1, has been developed in response to new ABMS and ABPN maintenance of certification requirements. This tool provides psychiatrists with an opportunity for practice improvement in a clinical area that poses a substantial burden of injury, morbidity, and mortality across multiple psychiatric diagnoses.

This PIP tool was developed by first identifying key evidence-based assessment and treatment recommendations from practice guidelines of the APA, Veterans Administration and Department of Defense (VA/DoD), and the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). The APA sources included the

Practice Guideline for the Assessment and Treatment of Patients with Suicidal Behaviors (

2) (2003),

Practice Guideline for Psychiatric Evaluation of Adults (

35) (2006),

Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Substance Use Disorders (

36) (2006),

Guideline Watch: Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Substance Use Disorders (

37) (2007),

Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Major Depressive Disorder (

38) (2010),

Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Borderline Personality Disorder (

39) (2001), and the

Guideline Watch: Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Borderline Personality Disorder (

40) (2005). The VA/DoD sources included the

Clinical Practice Guideline: Management of Major Depressive Disorder (

41) (2009) and the

Clinical Practice Guideline: Management of Bipolar Disorder in Adults (

42) (2010). The NICE Clinical Guideline resources included

Depression: The Treatment and Management of Depression in Adults (

43) (2009) and

Schizophrenia: Core Interventions in the Treatment and Management of Schizophrenia in Adults in Primary and Secondary Care (

44) (2009).

These evidence-based practice guidelines were developed through systematic medical literature reviews and critical evaluation of scientific research by experts in the field of suicide as well as individuals with expertise in other areas of psychiatry, including depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia. Thus, the PIP tool presented here is based on the best available evidence for comprehensive assessment and treatment of adults with suicidal ideation and behavior. Although several of the practice guidelines that have been referenced are more than 5 years old, core recommendations that have been highlighted in the PIP tool are still considered best practice.

The

Performance in Practice Physician Practice Assessment Tool for Assessment and Treatment of Adults at Risk for Suicide and Suicide-related Behaviors presented in

Appendix 1 is designed to facilitate retrospective chart review of the core components of a comprehensive evaluation for risk of suicide and suicide-related behaviors, as a part of psychiatric evaluation for patients with any psychiatric diagnoses.

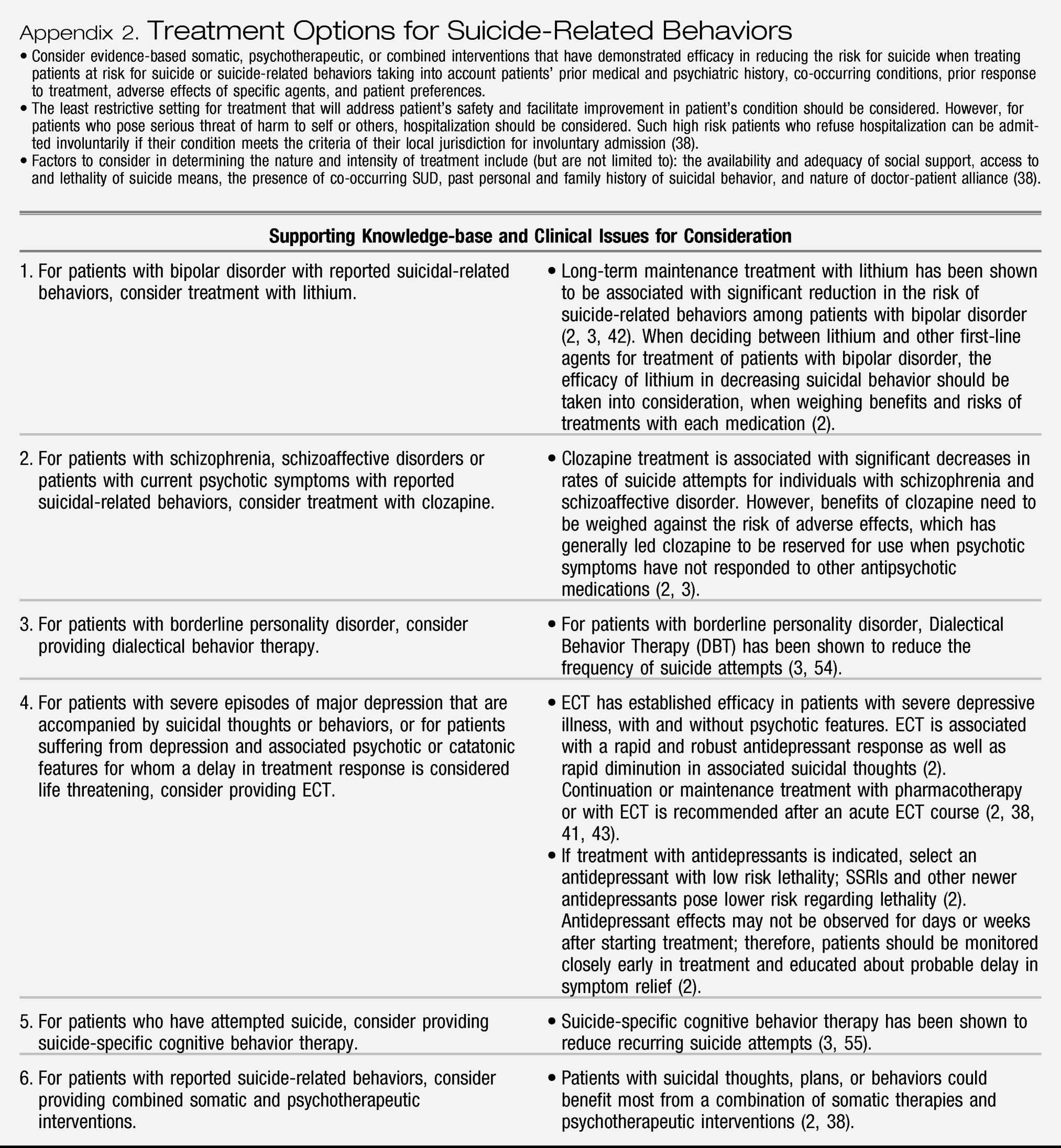

Appendix 2 provides a general review of evidence-based treatment(s) specifically targeting suicide-related behaviors. Each of the appendices attempts to highlight aspects of care that are evidence-based and have significant public health implications where gaps in guideline adherence are common. The last column of each appendix provides guideline-supported recommendations, knowledge-base and resources to assist in practice improvement efforts. Quality improvement opportunities that arise from using this tool can generally be managed by individual psychiatrists and applied as a part of their routine practice, rather than relying on other health care system resources.

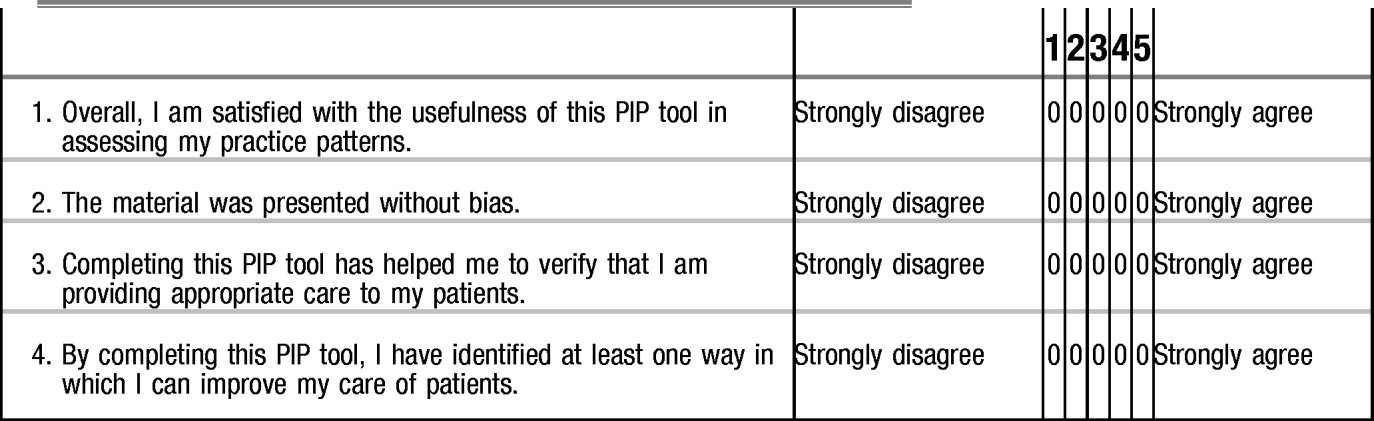

The PIP tool has been designed to be relevant across clinical settings (e.g., inpatient and outpatient), is straightforward to complete, and is usable in a pen-and-paper format to aid adoption. In addition to its value as a self-assessment tool, this form could be also used for MOC retrospective peer-reviewed initiatives. Although the ABPN MOC program requires review of at least five patients as part of each PIP unit, larger samples will provide more accurate estimates of quality of care within a practice.

After using the PIP tool to assess the pattern of care provided to patients, the psychiatrist should determine whether specific aspects of care need to be improved. Through such practice assessment, the psychiatrist may determine that deviations from the quality indicators are clinically appropriate and justified, or he or she may choose to acquire new knowledge and modify his or her practice to improve quality. For example, if patients in the psychiatrist's current psychiatric caseload are not adequately assessed for suicide-related behaviors, then an area for improvement could involve implementation of systematic assessment for suicidal ideation and behaviors across all patients.

It is important to note, however, that although this tool is intended to highlight current evidence-based assessment and treatment recommendations for patients at risk for suicide-related behaviors, justifiable variations from recommended care are expected. Assessment and treatment recommendations provided in the practice guidelines are generally intended to be relevant to the majority of individuals (

45,

46). However, practice guidelines and quality indicators are often derived from findings of efficacy and effectiveness trials where stringent enrollment criteria are used; thus individuals in clinical trials often differ in important ways from those seen in routine clinical practice (

47). Moreover, patients vary widely in their clinical presentations, presence of comorbid physical and psychiatric conditions, response to treatment, and other factors, thus influencing clinical decision making.