There is considerable clinical and empirical evidence regarding the common co-occurrence of chronic pain and the anxiety disorders. The primary purpose of this clinical synthesis is to describe the core features of clinically significant pain experiences and to introduce anxiety disorder practitioners to efficient assessment and management methods. To achieve this purpose, it is necessary to define pain and its clinically significant chronic manifestation that frequently co-occur with the anxiety disorders, present data on the prevalence of co-occurrence, describe biopsychosocial models posited to account for the co-occurrence, and provide recommendations for improving assessment and treatment of patients who present with an anxiety disorder accompanied by significant pain. We also discuss directions for advancing this growing field of inquiry.

BIOPSYCHOSOCIAL MECHANISMS

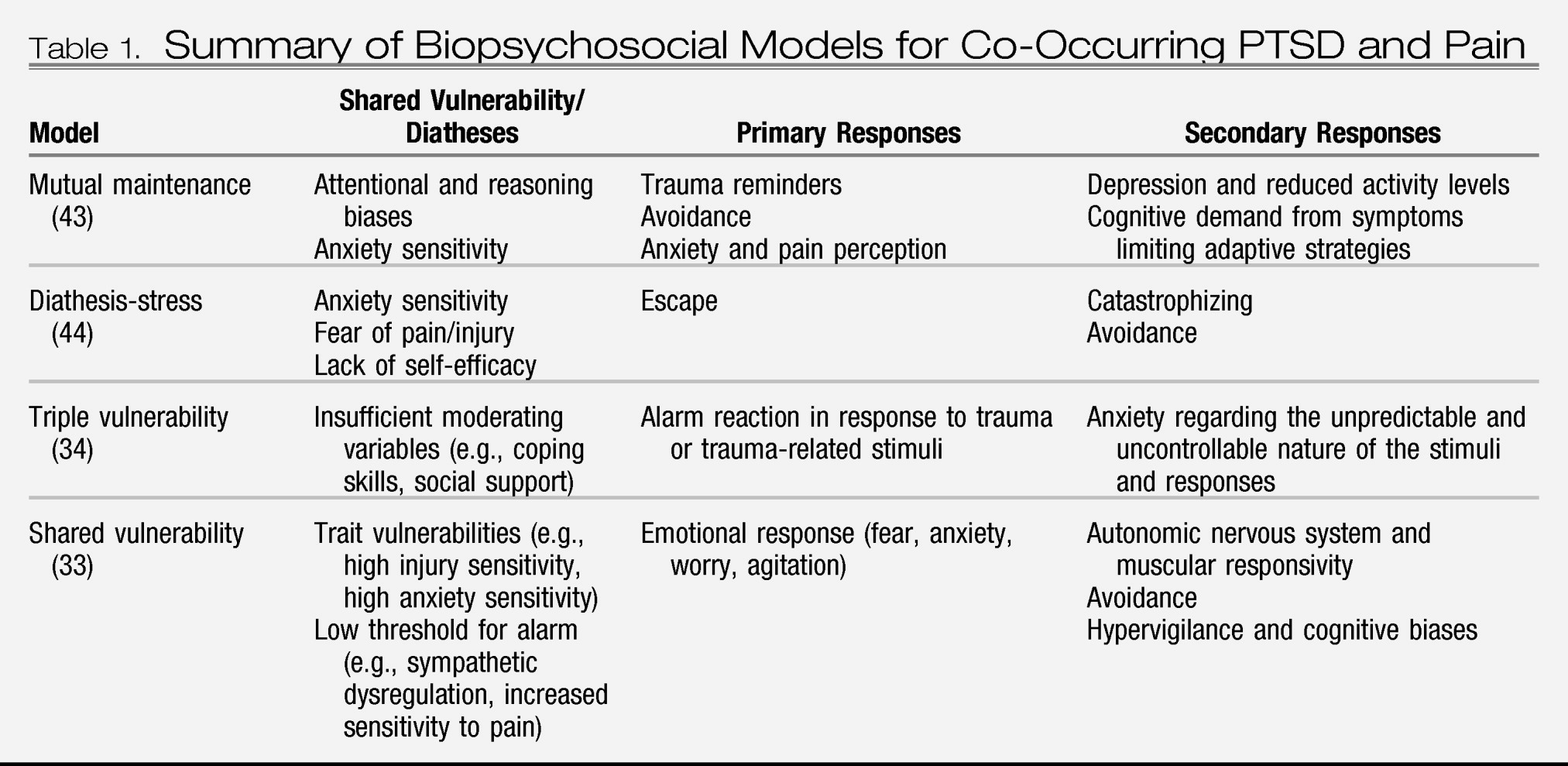

Beyond studies on prevalence and temporal relationships of co-occurring anxiety disorders and chronic pain, theoretical and empirical work has been limited primarily to PTSD. Several biopsychosocial models have been proposed to account for the substantial co-occurrence of PTSD and chronic pain and identify associated mechanisms. These models, each representing slightly different iterations of the self-perpetuating interplay between PTSD and chronic pain that sustains distress and functional disability, include the mutual maintenance model (

43), the shared vulnerability model (

33), and several related iterations thereof (

34,

44). It is beyond the scope of this clinical synthesis to comprehensively detail these models; instead, we provide a general overview of the key aspects of these models (

Table 1).

The mutual maintenance model (

43) posits that the physiological, emotional, and behavioral components of PTSD maintain or exacerbate chronic pain and, likewise, that the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral components of chronic pain maintain or exacerbate symptoms of PTSD. Seven specific mechanisms of mutual maintenance (see the Shared Vulnerability/Diatheses, Primary Responses, and Secondary Responses columns of

Table 1), each of which may have an impact along several bidirectional pathways, are posited in the model. The model predicts that pain sensations experienced by a person with chronic pain will be persistent and arousal-provoking reminders of the event that lead to the pain experience. Physiological arousal in response to recollection of the trauma will, in turn, promote avoidance of pain-related activities and (over time) physical deconditioning, which makes the experience of pain more likely.

The shared vulnerability model (

33) and related iterations (

34,

44) suggest that some of the maintenance factors proposed in the mutual maintenance model denote shared vulnerability, or diathesis, for developing both conditions (see Shared Vulnerability/Diathesis column of

Table 1); accordingly, co-occurring PTSD and chronic pain are most likely to develop when a vulnerable person experiences an event that is both traumatic and painful, wherein subsequent trauma reminders and pain sensations trigger further negative emotion and associated functional disability.

Comprehensive reviews of related empirical work are provided elsewhere (

7,

45). These reviews highlight a complex and emerging body of literature in which some mechanisms (i.e., anxiety sensitivity, depression, pain perception) have received more attention than others (i.e., trait variables beyond anxiety sensitivity, avoidance behavior, attentional biases, autonomic nervous system dysregulation). Asmundson and Katz (

7) have recently extended the shared vulnerability model to the other anxiety disorders; however, its utility beyond PTSD awaits empirical scrutiny.

ASSESSMENT OF PAIN

Assessment of patients with anxiety disorders does not typically focus on clinically significant chronic pain or pain disorder. The lack of focus on pain experiences makes intuitive sense, given that the patient is often presenting to one specialist for help with their anxiety and to another specialist, if at all, for help with their pain; however, clinically significant chronic pain can be a critically complicating factor for both assessment and treatment of anxiety disorders. Results from randomized controlled trials comparing collaborative care with treatment as usual for PD or GAD indicate that pain severe enough to interfere with activities of daily living also interferes substantially with treatment success for anxiety (

46). Accordingly, clinicians working with patients with anxiety disorders should consider incorporating pain assessments into their standard practice to facilitate case conceptualization and treatment planning for those patients who also experience clinically significant pain.

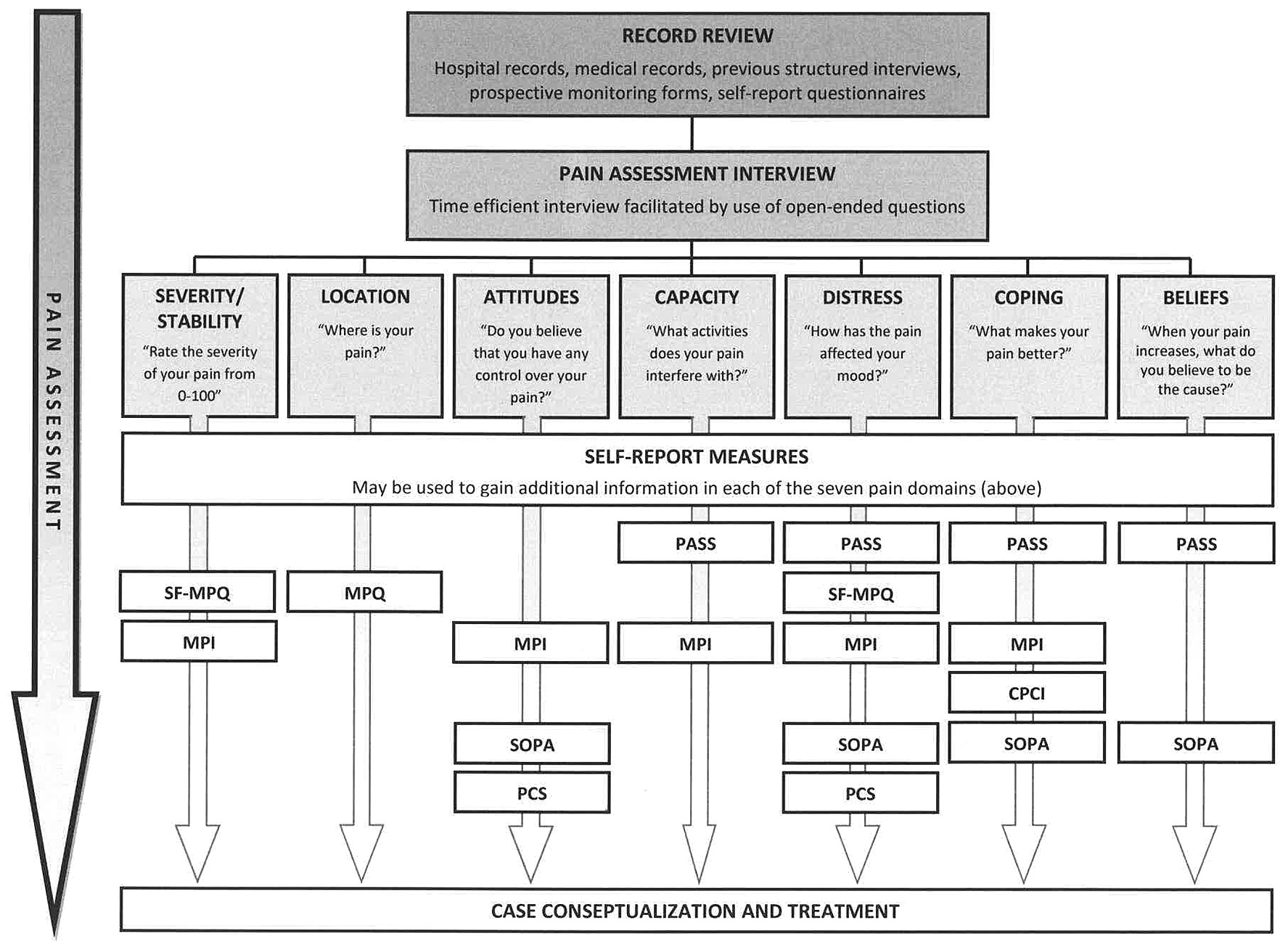

It is beyond the scope of this clinical synthesis to detail the complexities often associated with a comprehensive assessment of pain. Instead, we provide guidelines to facilitate a time-efficient yet reasonably comprehensive assessment (

47–

49). A time-efficient pain assessment focuses on seven key elements, including pain severity and stability, pain location(s), pain-related attitudes, pain-related beliefs, pain-specific emotional distress (i.e., fear, anxiety, and mood changes), pain-related coping styles, and pain-related functional capacity (

Figure 1). The latter is particularly important given that, as noted above, some patients with chronic pain function well despite their pain whereas others do not.

Assessment begins with an evaluation of patient records when available. These records might include hospital medical records, records from other health care providers (e.g., psychologists and physiotherapists), previous clinician-administered structured clinical interviews, previous clinician observation techniques (e.g., pain behaviors and facial action coding), prospective monitoring forms, and self-report questionnaires. Although the information obtained from patient records may provide essential information, particularly for those who have received services from a number of clinicians, a brief clinical interview is essential for determining current biopsychosocial functioning.

Key open-ended questions can be used to facilitate identification of pain characteristics (i.e., location, severity, and stability), pain triggers, patterns of avoidance, and treatment goals. These include, for example, “Where is your pain?”, “On a scale from 0 (

not at all) to 100 (

the worst possible), how bad is your pain right now? In general?”, “Is your pain always present?”, “What makes your pain worse?”, “What makes your pain better?”, “What entertaining activities does your pain interfere with?”, “What work activities does your pain interfere with?”, “What would you do tomorrow if you knew you'd have no pain just for that day?” These open-ended questions can be supplemented with a selection of brief self-report measures that serve to facilitate assessment and gauge treatment progress. Although we recommend a set of specific supplemental measures that correspond to the seven key elements of an efficient pain assessment, other options are available (for example, see

50).

The psychometric properties for the self-report measures listed below are described in detail elsewhere (

51,

52); as such, only the names and rationales for use are included here. The Short Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (

53) is used to describe the quality and intensity of the pain experience, using descriptors such as

throbbing and

cramping, with intensity indicated using a 4-point Likert scale (0 =

none to 3 =

severe). A visual analog scale and present pain intensity index also provide indices of current overall pain intensity. We also recommend that a body diagram, such as that included in the original long form of the McGill Pain Questionnaire (

54), be included as a means of assessing location of pain. The Multidimensional Pain Inventory (MPI) (

55) assesses physical, psychological, and social factors related to the pain experience and permits identification of subtypes of pain characterized, for example, by adaptive versus dysfunctional coping (

11). The Pain Anxiety Symptoms Scale (PASS) (

56) and its short form (

57) assess four theoretically distinct components of pain-related anxiety, providing useful information regarding pain-related cognition, emotion, and behavior. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) (

58) measures catastrophic beliefs regarding the consequences of anticipated or actual pain. The Survey of Pain Attitudes–Revised (SOPA) (

59) measures attitudes about the appropriate treatment of pain as well as the personal ability to control pain. The Chronic Pain Coping Inventory (CPCI) (

60) measures cognitive and behavioral strategies people might use in an attempt to prevent or relieve pain. Collectively, the PASS, PCS, SOPA, and CPCI provide a fairly comprehensive picture of cognitions and behaviors that may be contributing to the maintenance of pain and associated functional limitations. Finally, there is growing evidence that anxiety sensitivity—the fear of sensations related to anxiety (

61)—may denote a key mechanism in the co-occurrence of the anxiety disorders and clinically significant chronic pain. Accordingly, the Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3 (ASI-3) (

62), which assesses the dispositional tendency to fear anxiety-related sensations due to the belief such sensations signal harmful consequences, should also be considered for inclusion.

TREATMENT AND OUTCOMES

There are several evidence-based treatment options available for patients who present with an anxiety disorder accompanied by clinically significant chronic pain, including pharmacotherapy and several forms of psychotherapy. Combined pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy is also an option (

63), although additional research is needed to establish whether the combined approach produces better outcomes for pain and anxiety symptoms relative to monotherapy within the context of the various anxiety disorders.

Pharmacotherapy has been shown to be effective in alleviating chronic pain (

64,

65). The group of drugs known as the

adjuvant analgesics—drugs that have primary indications other than pain but contain analgesic properties—may be particularly useful for patients with an anxiety disorder who present with clinically significant chronic pain (

64). The adjuvant analgesics can be grouped according to the type of pain for which they are effective, including those for multiple pain types (e.g., tricyclic antidepressants, α

2-adrenergic agonists, corticosteroids, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors), those for neuropathic pain (e.g., anticonvulsants, γ-aminobutyric acid agonists, and neuroleptics), those for musculoskeletal pain (e.g., muscle relaxants and some benzodiazepines), and those for cancer pain (e.g., osteoclast inhibitors and anticholinergic agents). In the absence of systematic evidence on efficacies of specific drugs for patients presenting with both an anxiety disorder and clinically significant chronic pain, drug selection must be based on the evidence available from applications to patients with either an anxiety disorder or chronic pain, careful assessment of the patient, and good clinical judgment. To illustrate, given its effectiveness in alleviating headache (

66) and musculoskeletal pain (

64) as well as PD, PTSD, SAD, and GAD, the anticonvulsant gabapentin may be useful in treating patients presenting with one of these anxiety disorders and clinically significant chronic pain (

67–

69). Likewise, the large body of literature indicating effectiveness of tricyclic antidepressants for various anxiety disorders as well as clinically significant chronic pain suggests that these drugs may be useful for patients presenting with both. However, the decision to prescribe a particular drug, if any, needs to be placed in the context of the nature of the pain the patient is experiencing as well as his or her medication preferences and tolerance.

Cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) for chronic pain does not focus on reducing pain but, instead, on improving mood, reducing pain-related catastrophic thinking, and increasing functional ability despite pain. The intensity of CBT (i.e., number of sessions) varies as a function of the severity of functional disability, with 10 to 20 hours typically delivered in once or twice weekly hourly sessions. Comprehensive reviews of CBT for chronic pain indicate that it has modest positive effects that, at least in the case of improved mood and reduced catastrophic thinking, persist at 6 and 9 months follow-up (

70–

72). Dropout rates vary from study to study but are generally around 20% (

73). Because CBT has also been shown to be highly effective for the anxiety disorders (

74), it seems reasonable to assume that treatment of clinically significant chronic pain in patients with an anxiety disorder may effectively integrate elements of CBT for both the anxiety disorder and chronic pain. There have to date been no published systematic evaluations of such an integrated treatment approach, although findings from case studies appear promising (

75). Other promising options include provision of treatment as usual for a given anxiety disorder, or treatments that target putative shared mechanisms. As with the integrated treatment approach, there has been little systematic evaluation of these alternatives. Although results are preliminary, Shipherd et al. (

76) have demonstrated that treatment as usual for veterans seeking treatment for PTSD (i.e., a 16-week group-based outpatient CBT program, combined with pharmacotherapy for most patients) resulted in reductions in pain over the course of PTSD treatment for those reporting chronic pain before treatment.

Strategies for targeting putative shared mechanisms remain in developmental stages and, to date, have focused primarily on the reduction of elevated anxiety sensitivity. This approach is predicated on the assumption that targeting the shared vulnerability will reduce severity of symptoms of both clinically significant chronic pain and the anxiety disorder. Interoceptive exposure (i.e., exposure to anxiety-provoking bodily sensations), a common component of treatment for various anxiety disorders (

77), has recently been shown to be effective in reducing both PTSD symptoms (

78) and fear of pain (

79); consequently, it may have significant potential as treatment for patients who present with a co-occurring anxiety disorder and clinically significant chronic pain. Likewise, because exercise can serve the dual purpose of physical reconditioning in patients with chronic pain (

80) and exposure-related amelioration of anxiety symptoms, particularly panic-related symptoms (

81,

82), it is an attractive consideration for the patient with both clinically significant chronic pain and anxiety symptoms. It remains to be determined whether these and alternative methods for targeting putative shared mechanisms prove effective when systematically scrutinized.