Initial deliberations by the DSM-V Anxiety, Obsessive-Compulsive Spectrum, Post-traumatic, and Dissociative Disorders Work Group focused on the nosological structure of the anxiety and depressive disorders. These deliberations were spurred in part by structural modeling studies that highlight a shared internalizing factor (

1,

2) and recommendations from Watson (

3) for collapsing mood and anxiety disorders into an over-arching class of “internalizing” disorders, with three subclasses: bipolar disorders (bipolar I, bipolar II, and cyclothymia); distress or “anxious-misery” disorders (major depression (MD), dysthymia, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)); and the fear disorders (panic disorder (PD), agoraphobia, social phobia (SOP) and specific phobia (SP)). The Work Group recognized that deliberations would be aided by knowing whether the anxiety disorders share

features of responding that define them and distinguish them from mood disorders, and/or that differentiate between anxious-misery and fear disorders. The nosological recommendations by Watson and others derive from structural analyses of symptom self-report data, which represent estimation of past responding and prediction of future responding. In this review, such data were complemented with measures of “on-line” cognitive, behavioral, psychophysiological, and neural responding in the presence of aversive stimuli.

1This study represents the work of the authors for consideration by the DSM-V Anxiety, Obsessive-Compulsive Spectrum, Post-traumatic, and Dissociative Disorders Work Group. Recommendations provided in this study should be considered preliminary at this time; they do not necessarily reflect the final recommendations or decisions for DSM-V, as the DSM-V development process is still ongoing.

The method of review was based on computer database searches of PubMed and PsychINFO for English language articles from 1994 through 2009, combined with reviews of reference lists from identified manuscripts, as well as the proceedings and/or monographs of the preparatory conference series for DSM-V, particularly the Stress-Induced and Fear Circuitry Disorders. (

4) Given the vast number of references produced, this review presents representative rather than complete citations. However, meta-analyses were cited when available, and conclusions were drawn when published findings converged from multiple, independently conducted sources (vs. single and/or dependent sources). Also, whenever the literature was divided on a particular topic, representative citations are presented for each argument.

STRUCTURAL ANALYSES OF SYMPTOM SELF-REPORT DATA

Goals

Diagnosis is based on the self-report of symptoms, whether provided solely by the patient or with the aid of a clinician's appraisal. In this section, we explore the structure of symptom self-report data, to evaluate the degree to which symptom reports share features in common across the anxiety disorders, making them distinct from mood disorders, and whether features of symptom self-report distinguish fear disorders from anxious-misery disorders. Later, we address the behavioral, physiological, cognitive, and neural correlates of symptom reports and diagnoses.

We begin with conceptualizing the terms “fear” and “anxiety,” since these constructs underlie the symptoms of anxiety disorders. Then, we consider whether self-reported fear and anxiety distinctly differ from each other and from depression. Finally, the relationship between symptoms of fear, anxiety and depression and existing diagnostic categories of anxiety and mood disorder is reported.

Defining fear and anxiety

The definition of fear and anxiety varies greatly [for a review, see Reference (

5)]. In this review, we use Barlow's (

5) concepts, in which; anxiety is a future-oriented mood state associated with preparation for possible, upcoming negative events; and fear is an alarm response to present or imminent danger (real or perceived). This view of human fear and anxiety is comparable to the animal predatory imminence continuum (

6). That is, anxiety corresponds to an animal's state during a potential predatory attack and fear corresponds to an animal's state during predator contact or imminent contact.

Lang (

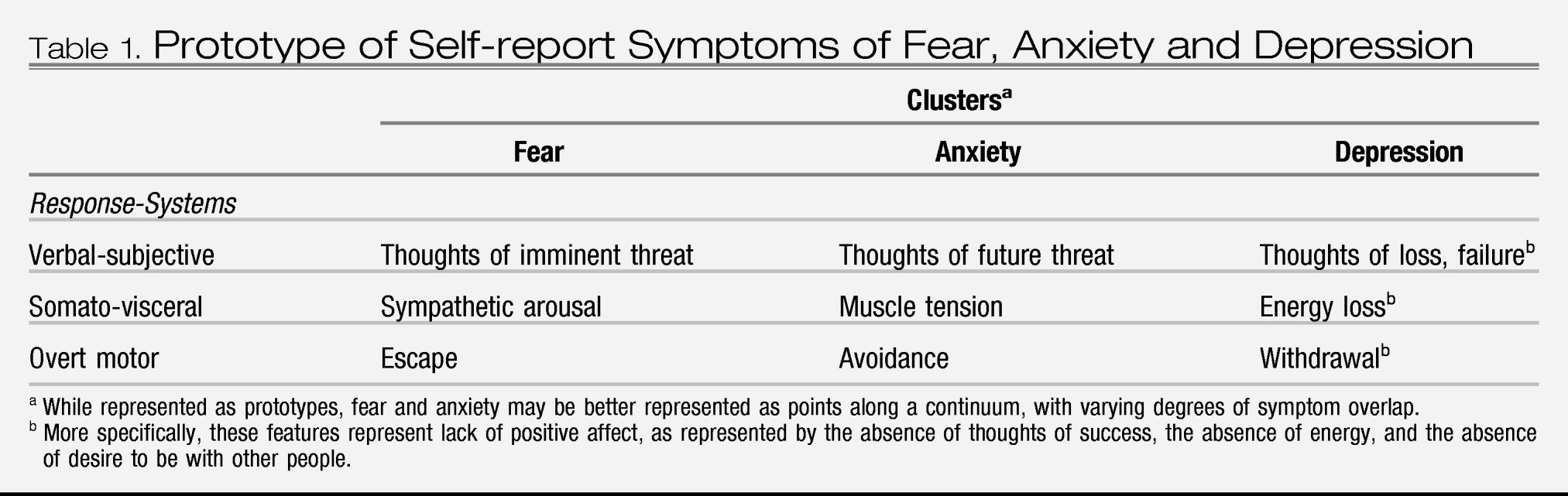

7) classified the symptoms of fear and anxiety into a system of three-responses: verbal-subjective, overt motor acts, and somato-visceral activity. In this system, and in accordance with the definitions of anxiety and fear, the symptoms of anxiety include worry (verbal-subjective), avoidance (overt motor acts), and muscle tension (somato-visceral activity). Fear symptoms include thoughts of imminent threat (verbal-subjective), escape (overt motor), and a strong autonomic surge resulting in physical symptoms such as sweating, trembling, heart palpitations, and nausea (somato-visceral) (

Table 1). Importantly, these descriptions represent prototypes of fear and anxiety that lie at different places upon a continuum of responding. Along such a continuum, symptoms of fear vs. anxiety are likely to diverge and converge to varying degrees. Zinbarg (

8) proposed a similar hierarchical model, with anxiety and fear as higher-order constructs that have effects on lower-order, partially-distinct response systems (i.e., verbal-subjective, overt motor actions, and somato-visceral activity).

Evidence for differentiating fear from anxiety

There is evidence to support the distinction between self-reported somato-visceral symptoms that are likely influenced by fear and self-reported subjective symptoms that are likely influenced by anxiety. For example, across four different samples of undergraduates, air force academy cadets, and psychiatric outpatients, a two-factor model was a better fit to the data than a one-factor model: the two factors represented physiological arousal (e.g., heart racing) and subjective anxiety (e.g., unable to relax and nervous) (

9). Similar findings have been demonstrated with other large community and undergraduate samples (

10) and with psychiatric out-patients, (

11) and in child and adolescent samples (e.g., (

12)). The factors are distinct but highly correlated. These data highlight a distinction between self-report of fear-linked physiological arousal and anxiety-linked subjective distress, but their linkages to the constructs of fear and anxiety, respectively, are only implied.

Differentiating fear, anxiety, and depression: evidence from the tripartite model

The large literature testing the tripartite model of fear, anxiety, and depression (

13) provides additional evidence for a distinction between self-reported somato-visceral symptoms of fear and verbal-subjective symptoms of anxiety. The tripartite model proposes that there are symptoms shared across “anxiety” and depression as well as symptoms unique to each. Shared symptoms typically are represented by a negative affect (NA) or general distress factor. Symptoms of anhedonia and the absence of positive affect are specific to depression whereas symptoms of physiological hyper-arousal are specific to “anxiety.”

Using the present terminology, the physiological hyperarousal items would be described as somato-visceral symptoms of fear. The subjective anxiety symptoms often are key markers of general distress. For example, when averaging factor loadings across five different samples (three student samples, an adult sample, and a patient sample), the item “worried a lot about things” had the second largest loading of any item on the general distress factor, (

14) and the same was true in a sample of child and adolescent psychiatric inpatients (

15).

Tests of the tripartite model demonstrate that somato-visceral symptoms of fear, symptoms of depression, and subjective symptoms of anxiety (along with other general distress symptoms) can be distinguished from each other. Such a distinction has been demonstrated in many samples, clinical and nonclinical, adult and child (e.g., (

14–

19)). As mentioned, although these factors can be distinguished from one another, they typically are moderately to highly correlated, albeit with some exceptions (e.g., (

15)).

Some studies have identified two rather than three factors (e.g., (

20)). The two-factor findings have been interpreted as symptoms of “anxiety” vs. symptoms of depression, without distinguishing fear from anxiety symptoms. However, these studies tend to rely on an insufficient number of items for independent measurement of fear and anxiety.

Relationship of DSM disorders to self-report symptoms of fear, anxiety, and depression

Only a handful of studies have examined whether different disorders load differentially on symptoms of fear and anxiety. One study with adult outpatients showed with zero-order correlations that autonomic arousal (somato-visceral symptoms of fear) was positively associated with constructs representing PD, GAD, SOP, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and MD, and that the correlation was significantly stronger with PD (0.89) than the other constructs (

18). Others also report greater correlations between somato-visceral symptoms of fear with PD than with GAD (

9,

21) or with MD (

9). Thus, whereas somato-visceral symptoms of fear seem to be associated with anxiety disorders in general, they may be of particular relevance to PD. In further support of this premise, when Brown et al. (

18) examined unique associations using all disorder constructs and negative affect as covariates, the PD construct was the only one to retain a significant, positive association with autonomic arousal. Also, the unique relationship between GAD and autonomic arousal was significant, but in the negative direction, suggesting a possible division between PD and GAD.

A similar specificity has been found between positive affect and both MD and SOP. That is, when structural models including multiple disorders and symptom constructs are considered, positive affect only displays significant associations with MD and SOP (

9,

18). Notably, the similarity between MD and SOP in this regard is at odds with the separation of SOP as a fear disorder from depression as an anxious-misery disorder.

Furthermore, in clinically referred children and adolescents, after controlling for the variance in physiological hyperarousal associated with negative affect, the somato-visceral symptoms of fear were significantly associated with clinical severity ratings for PD only and no other disorders of anxiety or depression (

22). Positive affect showed significant, negative associations with MD and SOP, whereas negative affect demonstrated significant, positive relations with PD, GAD, and OCD.

Limitations and future directions

The psychometric distinction between symptoms of fear and anxiety is potentially confounded by the measurement of different response systems, since most studies assess only somato-visceral symptoms of fear and only subjective symptoms of anxiety. For example, studies of SP stimuli typically measure how much fear is expected if a specific stimulus was encountered in the coming week, without any indicators of anxiety about the stimulus (e.g., worry about encountering, or avoidance of situations involving the stimulus). Thus, it is unclear whether symptoms load on different factors because they represent differences between symptoms of fear and anxiety or because they represent differences among response systems (i.e., verbal-subjective, overt motor, and somato-visceral).

Another limitation is that most studies employ nonstimulus-specific items. For example, physiological hyperarousal (e.g., heart pounding) items usually refer to the frequency or intensity of symptoms over a specified period (past week or two), without reference to an eliciting stimulus. Individuals who experience fear symptoms in the presence of circumscribed stimuli (e.g., air travel) may not encounter such stimuli over the specified period of time, and thus would score low on fear items. Similarly, even though they may worry about particular circumscribed stimuli as they become more probable (e.g., days before air travel), such individuals may not typically worry about those stimuli and hence would score low on symptoms of anxiety. In contrast, individuals with PD would be more likely to score high on items of fear, as would individuals with GAD be more likely to score high on items of anxiety, because they experience fear and anxiety, respectively, more frequently. In other words, nonstimulus-specific measures appear to represent frequency of fear and anxiety. However, frequency does not take into account the magnitude of response in the presence of specific stimuli or the frequency of exposure to specific triggering stimuli.

Hence, non-stimulus-specific items (as a measure of frequency) may be best complemented by stimulus-specific symptom items (as a measure of magnitude). For example, social anxiety symptom items might include: “I avoid parties” (overt motor acts), “when alone I worry about meeting new people” (verbal-subjective), and “I get tense and irritable from worrying about social situations” (somato-visceral). Social fear items could include: “I try to leave social situations as soon as possible” (overt motor acts), “when speaking in public, I think I look like a fool” (verbal-subjective), and “my palms get sweaty when eating in front of others” (somato-visceral). Patterns of covariation among such items would reveal whether or not a future-oriented social anxiety factor, indicated by avoidance of and worry about potential social situations, was separable from a present-focused social fear factor, indicated by escape from social situations as well as fearful thoughts and physiological arousal during social situations. With this kind of measurement, the extent to which each disorder is marked by symptoms of fear vs. symptoms of anxiety could be determined.

Summary and implications for DSM

The existing literature reveals that self-reported somato-visceral symptoms of fear (e.g., breathlessness) are separable from, yet related to, verbal-subjective symptoms of anxiety (e.g., worry a lot). Although verbal-subjective symptoms of anxiety are not always separable from other general distress symptoms, anxiety symptoms and fear symptoms generally are separable from, yet related to, symptoms representing anhedonia or the absence of positive affect (i.e., depression). The extent of the relationship between factors of fear, anxiety, and depression tends to be moderate-to-large, but can be quite modest depending on item content. While there is some evidence to indicate that several anxiety disorders are significantly, positively related to somato-visceral symptoms of fear, the relationship of these symptoms to PD seems to be stronger than with GAD. These findings lend support to a distinction between fear-based disorders and anxious-misery disorders. Symptoms of anhedonia are especially linked to both MD and SOP, thereby at odds with the proposed categorization of SOP as a fear disorder vs. anxious-misery disorder.

However, as noted, the limitations to existing self-report methodologies weaken the implications for DSM. That is, most studies are limited by the measurement of different response systems to assess fear (i.e., somato-visceral) vs. anxiety (i.e., verbal-subjective) symptoms as well as by restriction to nonstimulus-specific symptoms of fear and anxiety. Even when studies employ stimulus-specific items, they tend to address either fear or anxiety symptoms, but not both. Therefore, it is recommended that self-report items are developed that would better assess fear and anxiety symptoms across all three response modalities as well as in response to a range of stimuli.

CONCLUSION

The goal of this review has been to evaluate commonalities across anxiety disorders in features of responding in self-report estimation/prediction and in on-line responding to aversive stimuli across behavioral, psychophysiological, cognitive domains as well as functional systems at the neural level. We addressed whether a category of fear disorders (i.e., PD, PTSD, SOP, and SP) is distinctly identifiable from anxious-misery disorders (i.e., GAD and depression), and more broadly whether anxiety disorders are distinct from depression.

In terms of symptom self-report, the anxiety disorders are characterized by prototypical fear, com-prised of escape behaviors, physiological arousal, and thoughts of imminent threat, and prototypical anxiety, comprised of avoidant behaviors, tension, and thoughts of future threat. These symptoms are related to, but also distinct from, symptoms of depression. There is some indication that self-reported symptoms of physiological arousal, as a measure of the construct of fear, relate more positively to PD and more negatively to GAD than other anxiety disorders, thereby supporting a distinction between fear and anxious misery disorders. On the other hand, lack of positive affect appears to be strongly associated with both depression and SOP, which is at odds with the proposed subdivision of disorders. However, limitations to self-report methodologies render these findings preliminary and in need of further development.

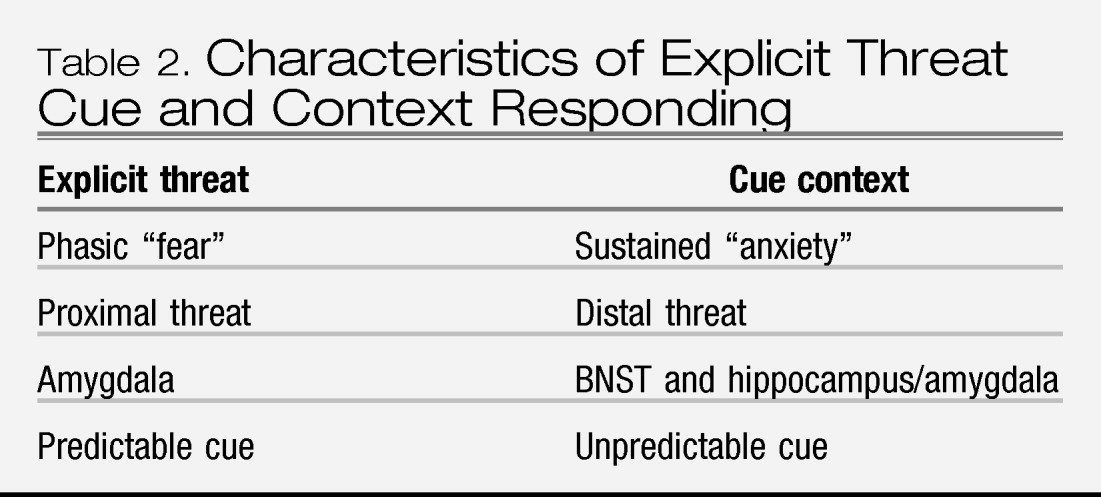

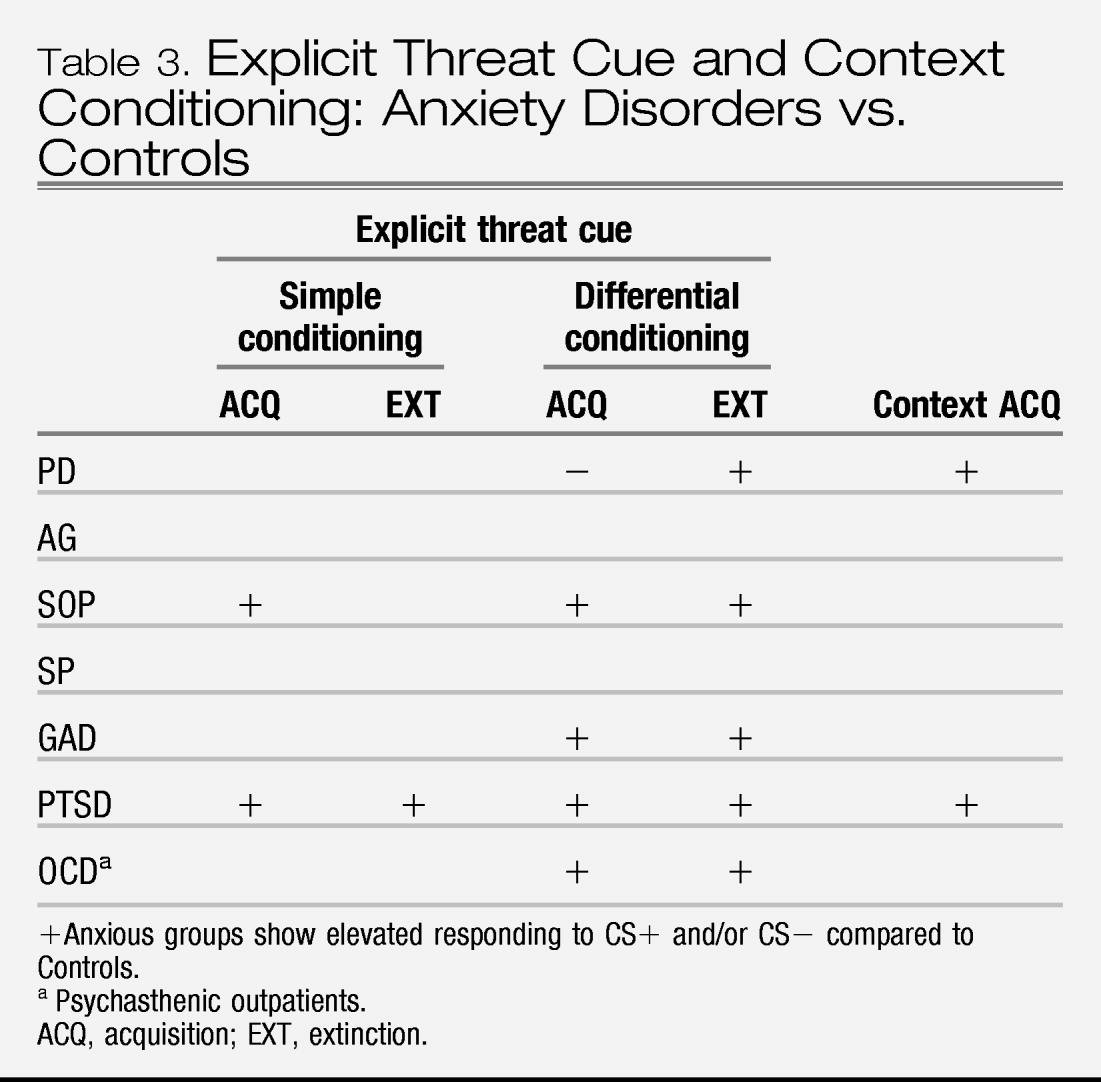

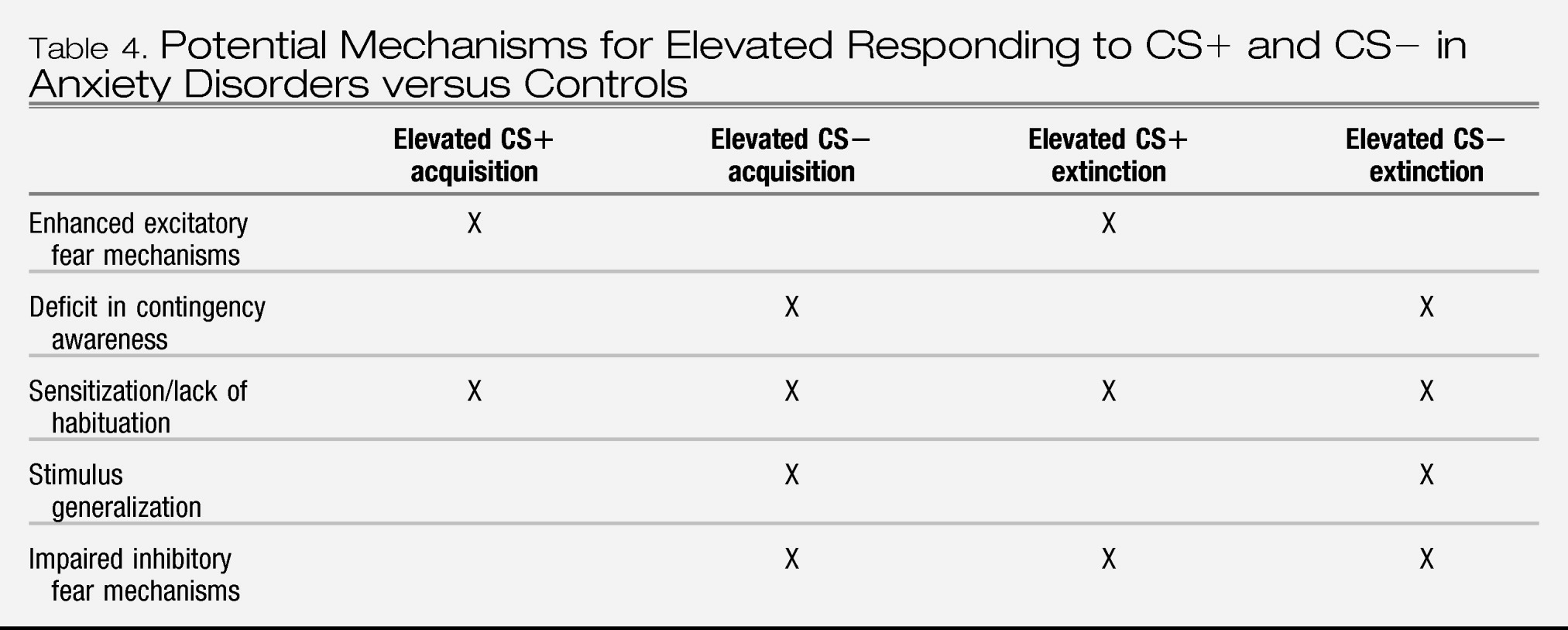

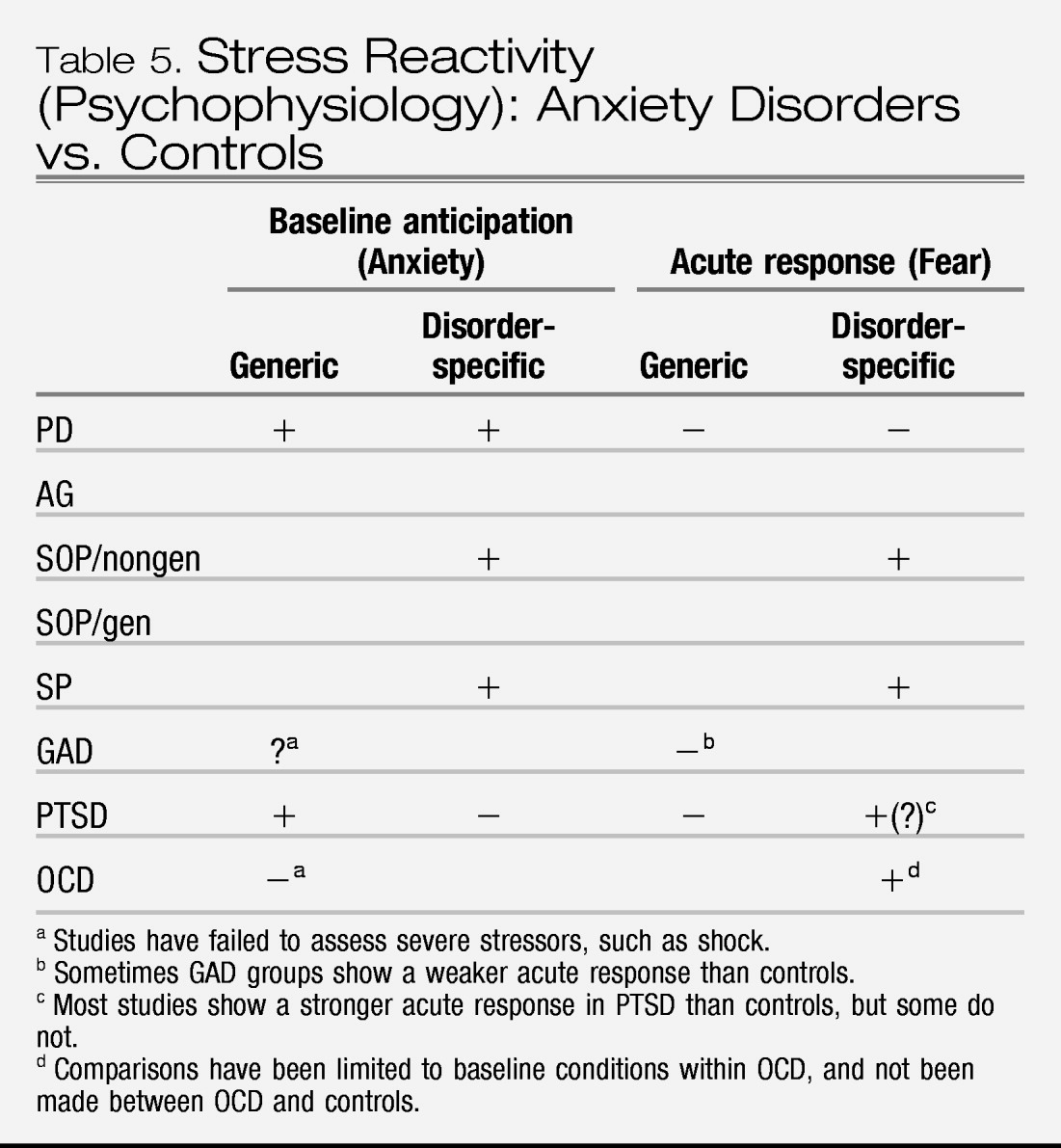

Together, the bodies of research on Pavlovian conditioning and stress reactivity indicate that, compared to controls, individuals with anxiety disorders show a sensitivity to threat that is expressed in terms of both fear and anxiety responding. More specifically, anxiety disorders are associated with (1) elevated fear responding to cues that signal threat (CS+), (2) elevated fear responding to cues that signal no threat (CS−) when presented in the context of threat, and to cues that formerly signaled threat (i.e., extinction trials), (3) elevated contextual anxiety in contexts and waiting periods (baselines) in which sufficiently aversive stimuli are anticipated, (4) equivalent acute responses to generic stressors, and (5) elevated responses to disorder-specific (personally relevant) stressors. However, these findings have not been fully evaluated across all anxiety disorders and/or are not entirely consistent across all the anxiety disorders that have been tested; only preliminary data suggest greater baseline anticipatory and acute fear responding to disorder-specific stressors in SOP and SP relative to PTSD and PD, and greater baseline anticipatory responding to generic stressors in PTSD and PD.

With respect to our question of “what is an anxiety disorder” these findings imply that anxiety disorders are characterized by elevated sensitivity to threat. However, the nuances of that sensitivity, and whether it discriminates anxiety disorders from depression or fear disorders from anxious misery disorders is undetermined. For these reasons, data from studies of Pavlovian conditioning and stress reactivity do not justify revisions to the DSM nosology for anxiety disorders. Also for these reasons, there is a call for a great deal more research to address the gaps listed above.

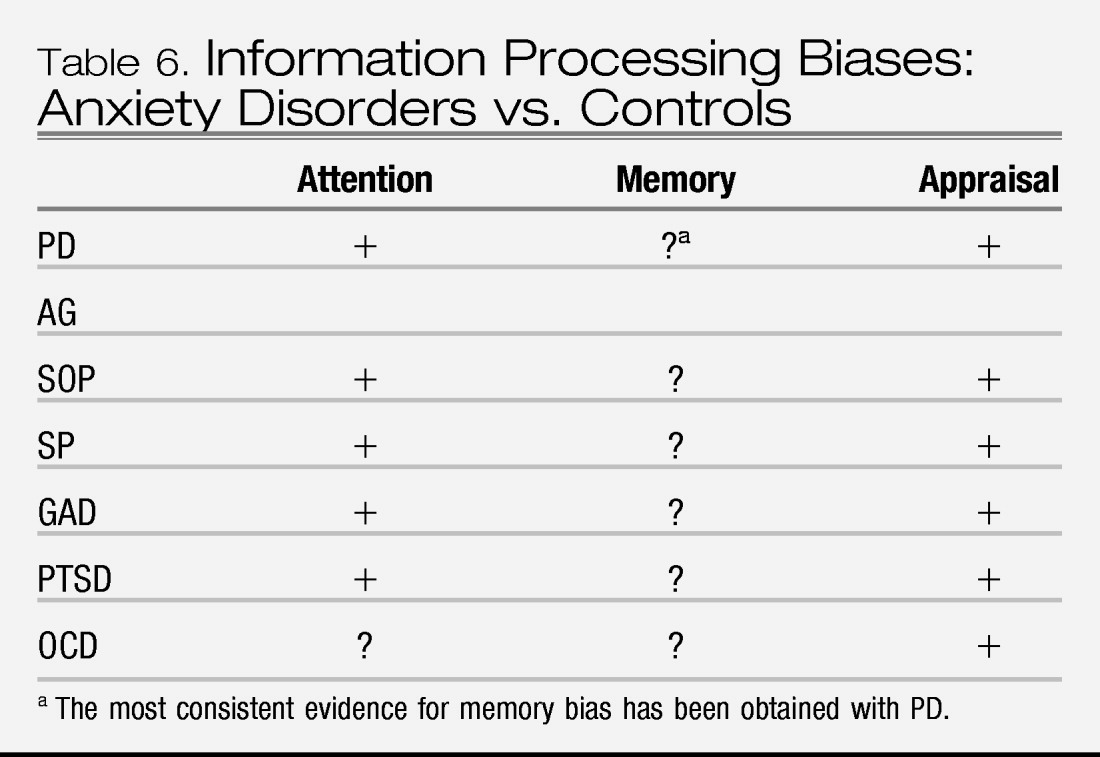

Data from measurement of cognitive biases indicates that the anxiety disorders are characterized by a preconscious attentional bias toward personally relevant threat stimuli, and a bias to interpret ambiguous information in a threat-relevant manner. Comparisons across subtypes of anxiety disorders are lacking and thus it is not known whether features of cognitive bias differentiate fear disorders from anxious-misery disorders. However, the cognitive bias data support the nosological distinction between anxiety and depression, with the latter characterized by a slower attentional bias to threat and a stronger memory bias for negative information relative to anxiety. Still, very few studies directly compare cognitive biases in anxiety and depression, such that the data are insufficient at this time to have direct relevance to changes to the nosology of DSM.

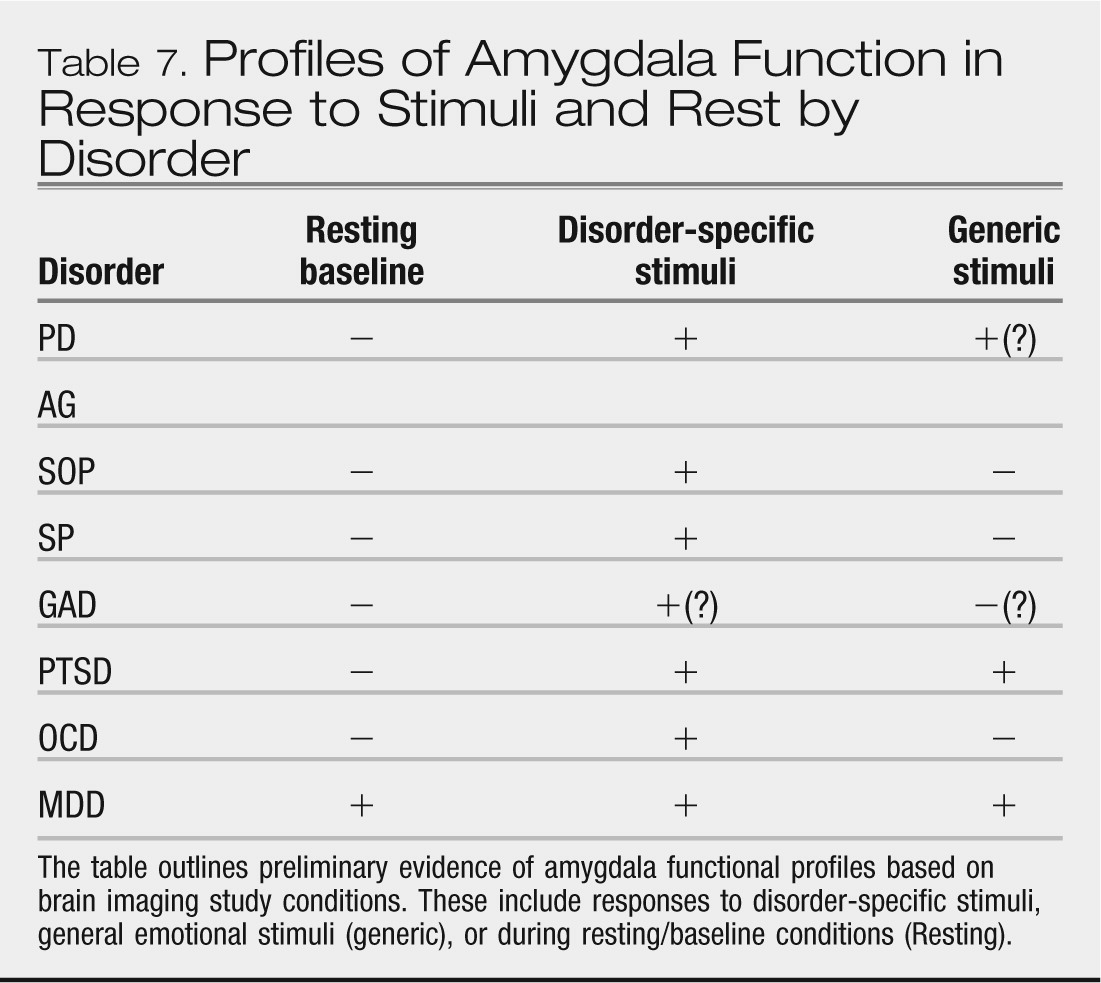

Data from neuroimaging studies indicate elevated amygdala responses to disorder-specific threat cues as a common characteristic across anxiety disorders. In contrast, amygdala responses to general threat cues may distinguish among anxiety disorders. However, the various profiles of amygdala response remain to be extended across development, to be well replicated, and to be sufficiently well studied in comparison groups to ascertain their specificity to anxiety vs. mood disorders. Similarly, while there is some indication that anxiety disorders are characterized by elevated insular, lateral OFC, and dorsal ACC responses as well as deficient responses within pgACC, vmPFC, and hippocampus, these profiles also remain to be thoroughly elaborated and replicated. Nevertheless, this implicated circuitry provides a heuristic model for the next step of research, whereby cognitive, behavioral, and physiological findings can be linked to mediating neuroanatomy and brain pathophysiology.

In summary, our review has helped to sharpen our knowledge of the features that characterize anxiety disorders. These features represent an elevated sensitivity to threat, as observed across symptom reporting, behavioral, cognitive and physiological responding, and underlying neural systems. However, the degree to which these features are differentiated between subtypes of anxiety disorders, or discriminate anxiety disorders from depression remain open to further investigation. One of the major barriers to such investigation is the high rate of co-morbidity within and across anxiety disorders and depression, and the associated overlap in diagnostic symptom criteria in some cases. Advances will most likely require dimensional approaches that evaluate both the shared as well as the unique contributions of fear, anxiety, and depression to the various facets of threat sensitivity.