Studies of the comorbidity of eating disorders and bipolar disorders in community populations

Seven studies have examined the co-occurrence of bipolar disorder and eating disorders in community populations (

9,

10,

15,

25–

31) (

Table 1). These studies differed in their inclusion of threshold versus subthreshold disorders and subject demographics.

Three community surveys included only adults (

10,

15,

25). Fogarty et al. (

25) evaluated 3,258 residents of Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, aged 18 years and older using the Diagnostic Interview Schedule and DSM-III criteria and found no overlap between the 22 (0.6%) persons with lifetime bipolar I disorder and the 4 persons (0.1%) with lifetime AN (

25). There was also no diagnostic overlap between persons with major depressive disorder and those with AN (

32). Other types of bipolar and eating disorders, including subthreshold forms, were not assessed.

Angst (

15)evaluated 4,547 adult residents of Zurich, Switzerland, for the co-occurrence of binge eating (defined as ≥4 binge eating attacks/year) with hypomania (defined according to several thresholds) (

15). Compared with individuals with depression and healthy control subjects, individuals with hypomania, regardless of threshold definition, had higher rates of binge eating. Thus, for individuals with hypomania according to DSM-IV criteria, the rate of binge eating was 13%; for individuals with brief (<4 days) recurrent hypomania, the binge eating rate was 22%; for individuals with sporadic brief hypomania, it was 15%; and for individuals with mania, it was 14%, compared with 11% for individuals with depression and 5% for healthy control subjects. There was a trend for binge eating to be more common in people with hypomania than in those with depression (p=0.06).

In the third study, 2,980 respondents aged 18 years and older from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication were evaluated with the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) by Hudson et al. (

9). Bipolar disorder (defined as DSM-IV bipolar I and II disorder) was significantly more common in adults with BN (odds ratio 4.7, 95% confidence interval 2.1–10.8), BED (3.6, 2.1–6.3), and any binge eating (defined as binge eating episodes occurring twice a week for at least 3 months) (3.5, 2.0–6.1) but not in adults with AN (0.8, 0.2–3.7) or in subthreshold BED (3.0, 0.9–9.8). Specifically, bipolar disorder was present in 17.7% of those with BN, 12.5% of those with BED, and 12% of those with any binge eating compared with 3% of those with AN and 10.5% of those with subthreshold BED.

Of note, CIDI questions closely paralleled DSM-IV BED criteria, except that DSM-IV requires a minimum duration of 6 months of regular binge eating episodes and the CIDI asks whether the individual experienced symptoms for 3 months. However, proposed BED criteria for DSM-5 include binge eating episodes for 3 months rather than 6 months (

20). Overlap of eating disorders with subthreshold forms of bipolar disorder was not assessed.

The other four surveys of community populations included pediatric or young adult samples (

10,

26–

31). Evaluating 2,548 individuals aged 14–24 years using DSM-IV criteria, Wittchen et al. (

26) reported that 9% of individuals with hypomania or major depressive disorder and 8% of individuals with mania had a lifetime history of an eating disorder. The odds of having an eating disorder were significantly higher than those in the general sample for the individuals with hypomania (1.8) or major depressive disorder (2.7) but not mania (2.1). Specific types of bipolar disorder and eating disorders were not provided.

Lewinsohn et al. (

27–

30) assessed 1,710 randomly selected high school seniors in Oregon aged 14–18 years for DSM-III-R bipolar and eating disorders using the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children. There was no significant overlap between bipolar and eating disorders when full DSM-III-R threshold criteria were used to define syndromes (

27). However, subthreshold bipolar disorder was significantly associated with subthreshold and threshold eating disorders (

30). The authors followed a subset of 810 female subjects for 1 year and 534 subjects until their 24th year of age, separating the group according to three eating disorder categories: subjects with full syndrome eating disorders (N=19, 7 with AN), subjects with partial syndrome eating disorders (N=23, 9 with AN), and subjects with no eating disorder (N=768) (

29). As in the overall sample, there were no significant differences in the rates of syndromal bipolar disorder between the groups with full (0%) or partial syndrome (4%) eating disorders and the group with no eating disorders (5%). However, when subthreshold bipolar disorders were included, significantly higher co-occurrence rates were found in the full syndrome (26%) and partial syndrome (22%) eating disorder groups compared with the no eating disorder (4%) group.

Lewinsohn et al. (

29) introduced two other female comparison groups at the 24 years of age evaluation based on psychopathology identified at age 18 years: individuals with depression (N=207) and those without a mood disorder (N=83). At age 24 years, the full syndrome and partial syndrome eating disorder groups had significantly higher period prevalence rates of bipolar disorder (11% and 8%, respectively) compared with the depressed (0.5%) and no disorder (0%) groups.

In the third study, an analysis of interview data from 2,363 people aged 14 years or older randomly selected from central Italy, subjects with subthreshold bipolar disorder (bipolar disorder that failed to fulfill DSM-IV criteria for bipolar I or II disorder, 4.7% of the population) had significantly greater comorbidity with AN (4.3%) than those with unipolar depression (0.7%) (

31). Rates of AN did not differ significantly among subjects with bipolar disorder (4.0%) and those with unipolar depression, nor did they differ among subjects in the three different mood disorder groups for bulimia nervosa, in which rates were low, ranging from none for full-spectrum bipolar disorder to 1.3% for unipolar depression. Rates of eating disorders were not compared with those in the group without mood disorders.

In the final study, a nationally representative sample of 10,123 adolescents aged 13–18 years from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement were evaluated with the CIDI by Swanson et al. (

10). AN and BN were evaluated by DSM-IV criteria and BED by the proposed DSM-5 criteria (

20). Bipolar disorder (defined as bipolar I and II disorder by DSM-IV criteria) was significantly more common in adolescents with BN (adjusted odds ratio 7.3, 95% confidence interval 3.1–17.2) and BED (3.0, 1.5–5.7), but not in adolescents with AN (0.7, 0.1–4.9), subthreshold AN (2.5, 0.7–8.2), or subthreshold BED (0.8, 0.5–1.5). Criteria for subthreshold AN included lowest body weight less than 90% of the adolescent's ideal body weight, intense fear of weight gain at the time of the lowest weight, and no history of another threshold-level eating disorder. Criteria for subthreshold BED included binge eating at least twice a week for several months, perceived loss of control, and no history of another threshold-level eating disorder or subthreshold AN.

Taken together, six of these seven community surveys found that bipolar disorder and eating disorders significantly co-occurred in adolescents or adults, at least when subthreshold definitions of the disorders were considered (

9,

10,

15,

26,

29–

31). The pattern of comorbidity differed by age group. In the studies of adults only, bipolar disorder was associated with BN, BED, and binge eating, but not with AN (

9). Studies including pediatric populations similarly found links between bipolar disorder and BN and BED (

10). Associations that included AN were also found, but only when subthreshold definitions of bipolar disorder were used (

29–

31).

The finding of elevated comorbidity between eating disorders and subthreshold forms of bipolar disorder in female adolescents is particularly noteworthy, given the frequent presentation of eating disorders in this population, the early onset of bipolar disorder, and the increasing reorganization of subthreshold forms of bipolar disorder, including in pediatric populations (

33–

36). These data underscore the need to include the full spectra of bipolar and eating disorders in evaluating patients for the co-occurrence of these syndromes (

13,

14).

Co-occurrence, psychopharmacology, and pathogenesis

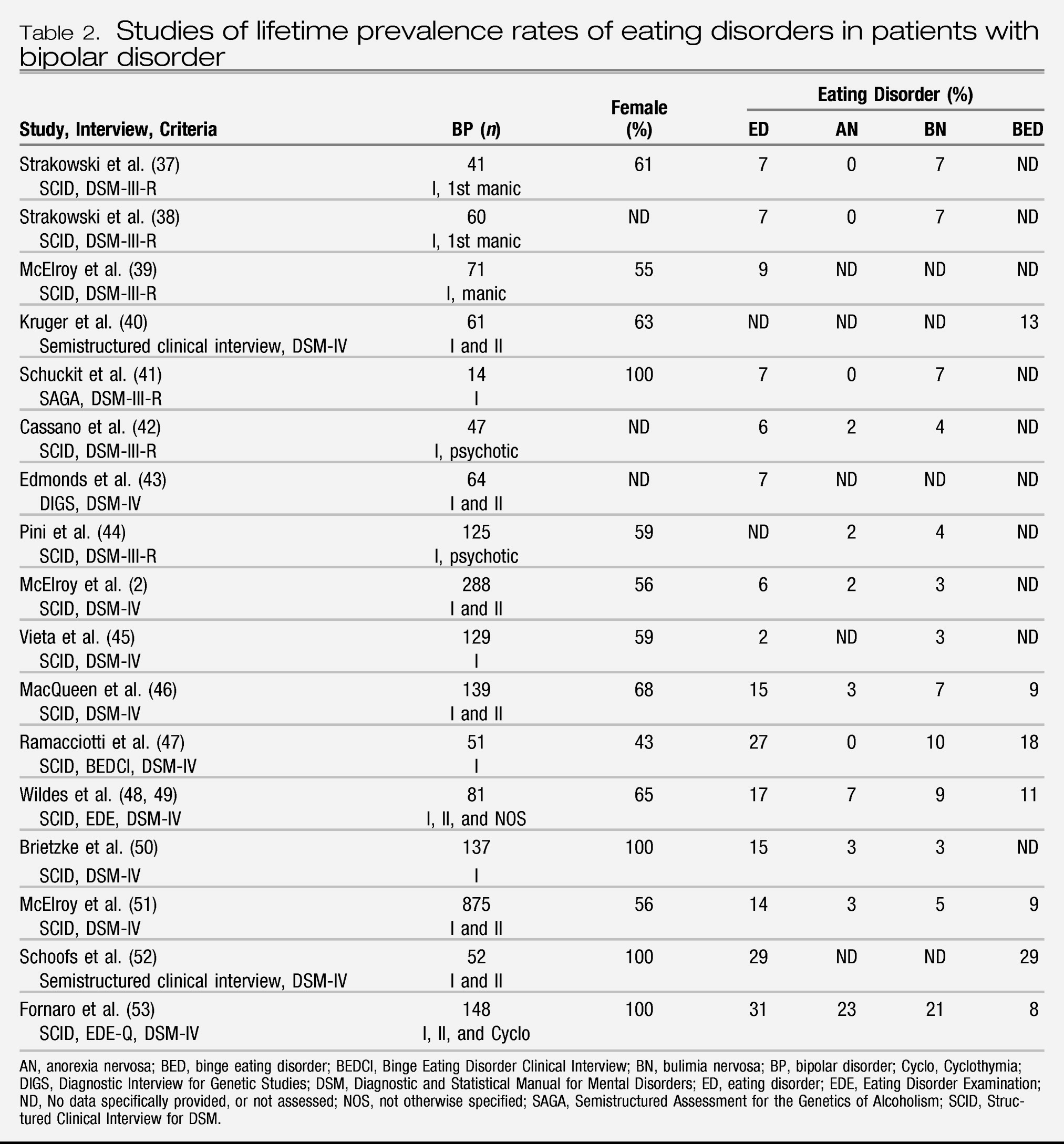

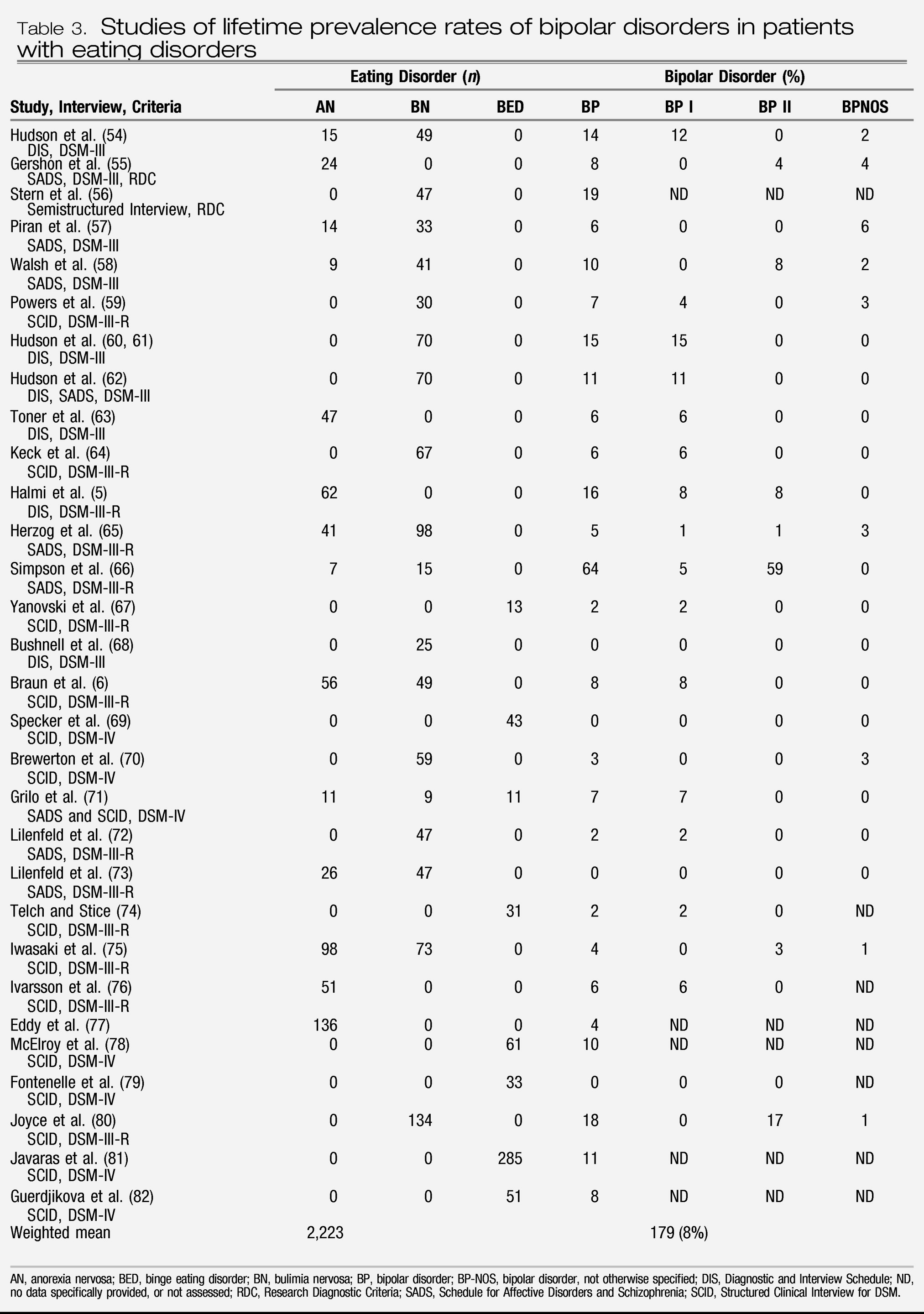

The data reviewed in this article indicate that bipolar disorder and eating disorders are frequently comorbid and may have some similar pharmacotherapy responses. Community studies indicate that bipolar disorder and eating disorders overlap significantly more often than their independent occurrence rates, especially when subthreshold or spectrum presentations are considered. Clinical studies indicate that patients with bipolar disorder have elevated rates of eating disorders compared with rates in the general population, whereas patients with eating disorders have elevated rates of bipolar disorder. Similar pharmacotherapy responses include response of mania and possibly AN to lithium and second-generation antipsychotics, response of BN, BED, and possibly bipolar depression to antidepressants, and lack of response of mania and AN to antidepressants, as well as reports of the emergence of hypomania or mania with antidepressant monotherapy in patients with both bipolar disorder and eating disorders.

In earlier articles, we discussed how these observations, along with others, such as similarly elevated comorbidity with anxiety and substance use disorders, suggest that bipolar disorder and eating disorders may be related by sharing a fundamental dysregulation of mood, eating behavior, and impulse control (

13,

14). Indeed, several authorities have hypothesized that impulsive behaviors, including overeating, may have mood-stabilizing effects (

155). Thus, just as persons with addictions may “self-medicate” with drugs of abuse and those with eating disorders may engage in eating disorder behaviors to reduce uncomfortable affect, some patients with bipolar disorder might self-medicate their affective instability with eating disorder symptoms such as binge eating, purging, or excessive exercise. Providing preliminary support for common biological underpinnings linking both conditions, investigators have found abnormalities in brain-derived neurotrophic factor, which is involved in the regulation of mood and appetite, in persons with bipolar disorder and those with eating disorders (

156–

158). Likewise, variants of the neurotrophic tyrosine kinase receptor 3 gene (

NTRK3) have been associated with early onset bipolar disorder and with eating disorders (

159,

160).

There are several therapeutic goals of the pharmacological treatment of patients with bipolar disorder and a co-occurring eating disorder. First, ideally the most parsimonious treatment would be with an agent effective in treating both syndromes. For example, a second-generation antipsychotic drug might be considered in a patient with bipolar disorder and AN. Second, consideration of agents for the treatment of one illness needs to be done in light of the potential for that agent to at least not exacerbate the other, either by therapeutic action or side effects. Thus, as comorbid BED or BN may be important correlates of obesity in bipolar disorder and certain mood-stabilizing and second-generation antipsychotic agents may be more likely than others to worsen binge eating, the exacerbation of unrecognized binge eating by such agents could be a cause of weight gain in some patients with bipolar disorder. Likewise, unrecognized bipolar disorder in patients with eating disorders could lead to treatment nonresponse and/or to manic symptoms if antidepressant monotherapy was being used to manage the eating disorder.

Third, the types of co-occurring bipolar disorder and eating disorders may differentially affect treatment options. Whereas a patient with bipolar I disorder and AN might respond optimally to a second-generation antipsychotic, a patient with bipolar II disorder and BED might do well with a serotonin reuptake inhibitor given alone or in combination with lithium, lamotrigine, or even topiramate. Last, and most significant, there are no randomized, controlled trials of any pharmacological agent specifically in the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder and a co-occurring eating disorder. Moreover, although a growing number of clinical trials have established the efficacy of a range of agents in the treatment of bipolar disorder, there are relatively few options for the psychopharmacological treatment of eating disorders. Thus, a familiarity with the growing field of eating disorder pharmacotherapy would be helpful for managing the patient with bipolar disorder with an eating disorder.