During symptomatic periods in bipolar outpatients undergoing treatment, depressive symptoms are three times as likely as manic symptoms to be present (

1–

3). This is notable both because most mood stabilizers are not as effective in treating the depressive phase of illness (they have an indication only in acute mania) and because many bipolar patients are treated with conventional antidepressants with or without the recommended mood stabilizers or atypical antipsychotics. Treatment with antidepressants in bipolar patients is common. A study of patients enrolled in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) (

4) found that 40% were on antidepressants. In a medical and pharmacy claims database study (

5), 50% of patients identified as having bipolar disorder were receiving antidepressant monotherapy (

5).

While antidepressants may be effective in some individuals with bipolar disorder (

6–

13), they can precipitate a rapid mood switch from depression to mania (

8,

14,

15), a phenomenon also known as treatment-emergent mania. More than 40% of patients enrolled in STEP-BD self-reported manic or hypomanic switch associated with antidepressant use (

16). In a retrospective study, Bottlender et al. (

17) evaluated clinical correlates of treatment-emergent mania in 158 bipolar I inpatients. Compared with patients who did not switch (N=119), those who developed treatment-emergent mania (N=39) had a significantly higher rate of tricyclic antidepressant use (80% versus 51%), a lower rate of lithium or anticonvulsant mood stabilizer use (59% versus 82%), and a higher number of mixed depressive symptoms (1.3 [SD=0.9] versus 0.8 [SD=0.7]). This small single-site retrospective study was not controlled, but it suggests that manic symptoms, in conjunction with use of tricyclic antidepressants and lack of mood stabilizers, may be associated with the switch process.

Although more recent controlled studies using newer agents and more conservative designs have reported reduced rates of treatment-emergent mania in comparison with the tricyclic antidepressant era, the percentage (5%– 20%) remains clinically significant (

6,

10,

14,

18,

19). While larger studies with longer-term follow-up and rigorous monitoring for manic symptoms are necessary to better delineate antidepressant causality versus natural course of illness, treatment-emergent mania is unequivocally an adverse outcome.

Mania is a volatile mood state characterized by poor judgment and marked impulsivity that can lead patients to engage in unsafe or personally damaging behaviors, often resulting in hospitalization, arrest, or incarceration (

20). Some studies have suggested that manic episodes may be associated with an episode-dependent neuroanatomic degeneration as measured by gray matter volume (

21) and

N-acetylaspartate (

22). Because even one manic episode can be potentially devastating, identifying risk factors can be clinically valuable.

In addition to tricyclic antidepressant liability (

23), a number of demographic and clinical risk factors have been reported in small or retrospective studies, including comorbid substance abuse (

24,

25), younger age (

26), decreased thyroid-stimulating hormone (

27), rapid cycling (

10), ss genotype at the serotonin transporter (

28,

29), bipolar I versus II subtype (

18,

19,

30), hyperthymic temperament (

31), mixed depressive symptoms (

17), past number of manic episodes (

32), absence of mood stabilizer (

33,

34), female gender (

32), and psychosis (

32). With the exception of the studies by Keck et al. (

32) and Altshuler et al. (

18), these studies were single site, retrospective, or small in sample size.

In this study, we evaluated clinical correlates of treatment-emergent mania in patients participating in the Bipolar Collaborative Network (formerly the Stanley Foundation Bipolar Network).

Method

Participating sites in this trial included the University of California, Los Angeles; University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas; University of Cincinnati; the National Institute of Mental Health; University of Utrecht, the Netherlands; and the Universities of Munich and Freiburg, Germany. Principal investigators at each site were responsible for obtaining approval from their respective institutional review boards. Patients 18–65 years old with bipolar disorder were recruited from academic settings, community mental health outpatient clinics, physician referral, and local advertisements. U.S. participants had to be able to read English. For the Dutch and German sites, the protocol and consent material were translated into Dutch and German, respectively. All participants provided written informed consent prior to evaluation and randomization. The overall study population and procedures have been described in detail elsewhere (

35,

36).

This study was a post hoc analysis focusing on demographic and clinical characteristics associated with antidepressant response and manic/hypomanic/mixed induction. We included data on all patients in the Stanley Foundation Bipolar Network with confirmed bipolar disorder who were depressed, were followed prospectively on a 10-week acute-treatment trial of an antidepressant, and were monitored with standard mood ratings. Our inclusion criteria were DSM-IV bipolar I or II depression, confirmed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (

37); current treatment with a mood stabilizer (lithium, valproate, carbamazepine, or lamotrigine) or treatment with an antipsychotic prior to antidepressant therapy; moderate depressive symptom severity, defined as a score ≥16 on the Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (

38); and a score of at least 3 (mildly ill) on the depression severity item of the Clinical Global Impression scale modified for use in bipolar disorder (CGI-BP) (

39). The SCID was administered by clinical research assistants who received training under the supervision of the principal investigator at their site; interrater reliability for the diagnosis of bipolar disorder was high, with an overall kappa score of 0.92 (

35). Patients were seen weekly for the first 2 weeks of the 10-week trial and then biweekly during the remaining 8 weeks. Symptom assessments were made with the Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) (

40), and the CGI-BP at each visit.

Based on these criteria, 184 patients had participated in at least one of the network's prospective 10-week acute adjunctive antidepressant trials. Details of the randomized, double-blind medication trial of adjunctive sertraline, venlafaxine, and bupropion have been reported elsewhere (

10,

19). Patients in this analysis took part in one to three different medication trials (mean=1.45, SD=0.71). When data from multiple trials were available for a single patient, we first evaluated whether the patient exhibited treatment-emergent mania in any of the trials; if so, then data from that trial were included in the analysis, and if not, then data from the first trial available were used.

The CGI-BP was used to classify participants in three groups: those with treatment-emergent mania or hypomania, those who did not respond to antidepressant treatment, and those who responded to antidepressant treatment. The CGI-BP severity of illness subscale allows separate ratings for severity of depression, mania, and overall illness. The scale ranges from 1 (not ill) to 7 (very severely ill). For the CGI-BP change score, the clinician is asked to rate, using all available information, the degree of change from the immediately preceding phase (in this case, the level of depression prior to randomization). The scale ranges from 1 (very much improved) to 7 (very much worse). The change from preceding phase on the CGI allows the clinician specifically to identify gradations of worsening of either depression or mania.

Treatment-emergent mania was defined as a CGI-BP manic severity score ≥4 (moderate) or a change score of 6 or 7 (much worse, very much worse) from the preceding phase at any time during the 10-week trial. Antidepressant nonresponse was defined as a CGI severity of depression score ≥4 (moderately ill or worse) or a change score ≥3 (minimally improved or worse response) from the preceding phase. Eight patients were identified as nonresponders solely as a result of side effects and were excluded from the analysis, leaving a sample of N=176. Antidepressant response was defined as completion of the acute trial with a CGI depression severity score of 1, 2, or 3 (not ill, minimally ill, or mildly ill) or a CGI change score of 1 or 2 (very much improved or much improved) from the preceding phase.

Because it was possible for some patients to meet criteria for more than one group, we used a hierarchical group assignment process. Assessments for assignment to the treatment-emergent mania group were done first. Patients who did not meet criteria for that group were then evaluated to determine whether they met criteria for the antidepressant nonresponse group, after which those remaining were assessed for eligibility for the antidepressant response group. In this design, the antidepressant response group not only met response criteria, they also did not meet any other group criteria. Likewise, the antidepressant nonresponse group not only met their own group criteria but also did not meet criteria for treatment-emergent mania.

Statistical analyses

Between-group differences in demographic or clinical characteristics were assessed using chi-square tests for categorical items and between-subjects analysis of variance for continuous variables. Because we have previously found that adjunctive venlafaxine was associated with a higher switch rate than sertraline or bupropion (

10,

19), we quantified the percentage of patients who were randomized to these antidepressants. A chi-square test for independence was done to determine whether there was a systematic relationship between treatment-emergent mania status and medications.

A second analysis evaluated between group differences in baseline symptom severity ratings on the Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology and the YMRS. For these analyses, four patients were excluded because baseline rating data were unavailable for them (N=172). Because the later YMRS data had a non-normal distribution (i.e., skew due to the large number of patients with no or mild manic symptoms), the analysis of variance and post hoc t tests were confirmed with generalized linear modeling based on a Poisson process.

Finally, an exploratory factor analysis was conducted defining facets of the overall constructs based on the four-factor solution suggested by the Kaiser criterion and using an orthogonal rotation using the varimax algorithm. We evaluated the relationship between the facets of the overall construct as defined by factor scores and the differences between the three groups.

Results

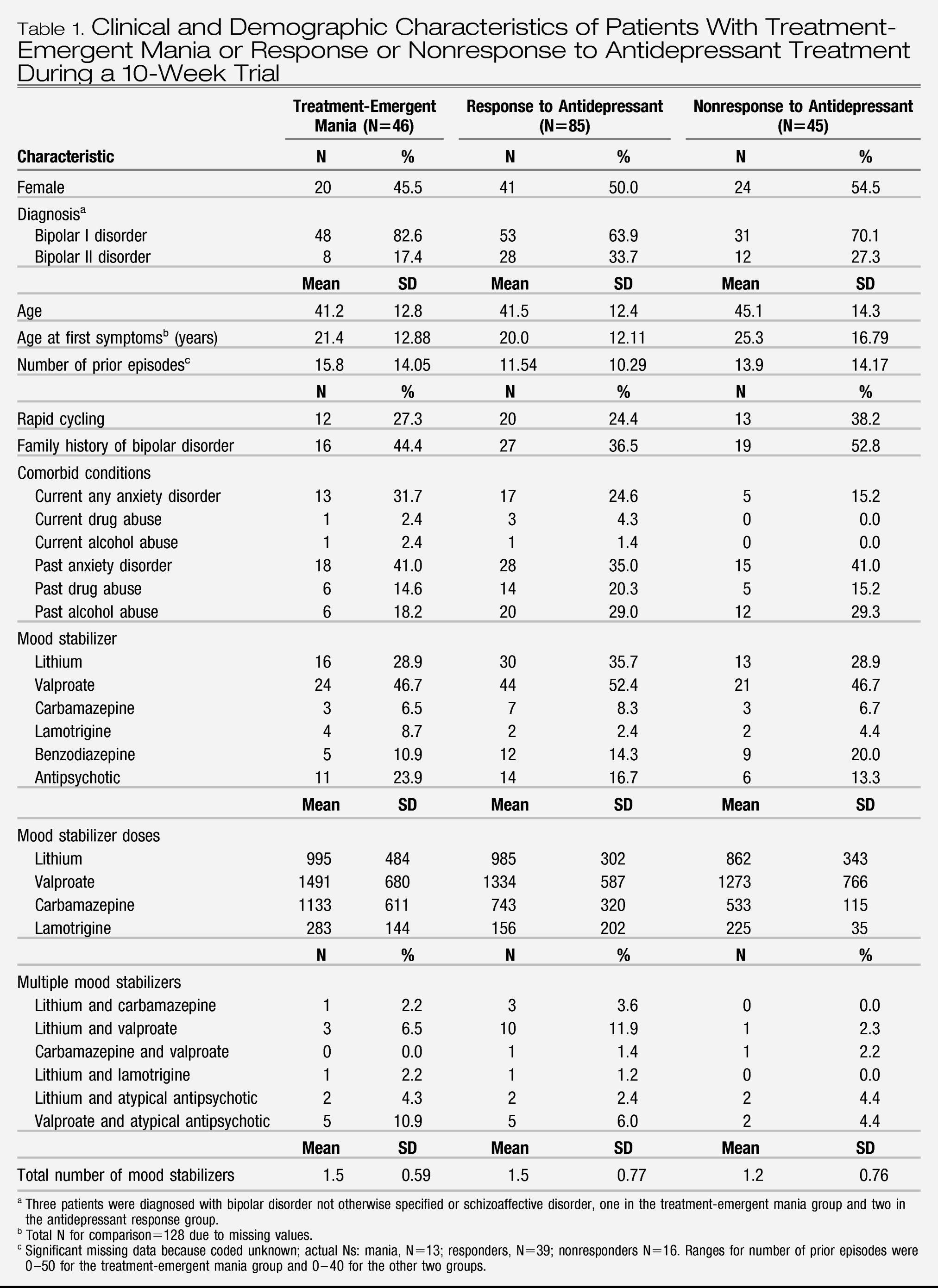

Table 1 summarizes the demographic and baseline clinical characteristics of the three groups; there were no significant differences between groups. There was no difference in the percentage of subjects who were treated with venlafaxine, sertraline, or bupropion in the three groups. Age, gender, age at first symptoms, number of prior episodes, percentage with rapid cycling, percentage with a family history of bipolar disorder, current or past comorbid disorders (alcohol, drug, or anxiety disorders), and use of mood stabilizers (dose and number of drugs used) did not distinguish the group with treatment-emergent mania from the antidepressant nonresponse and response groups.

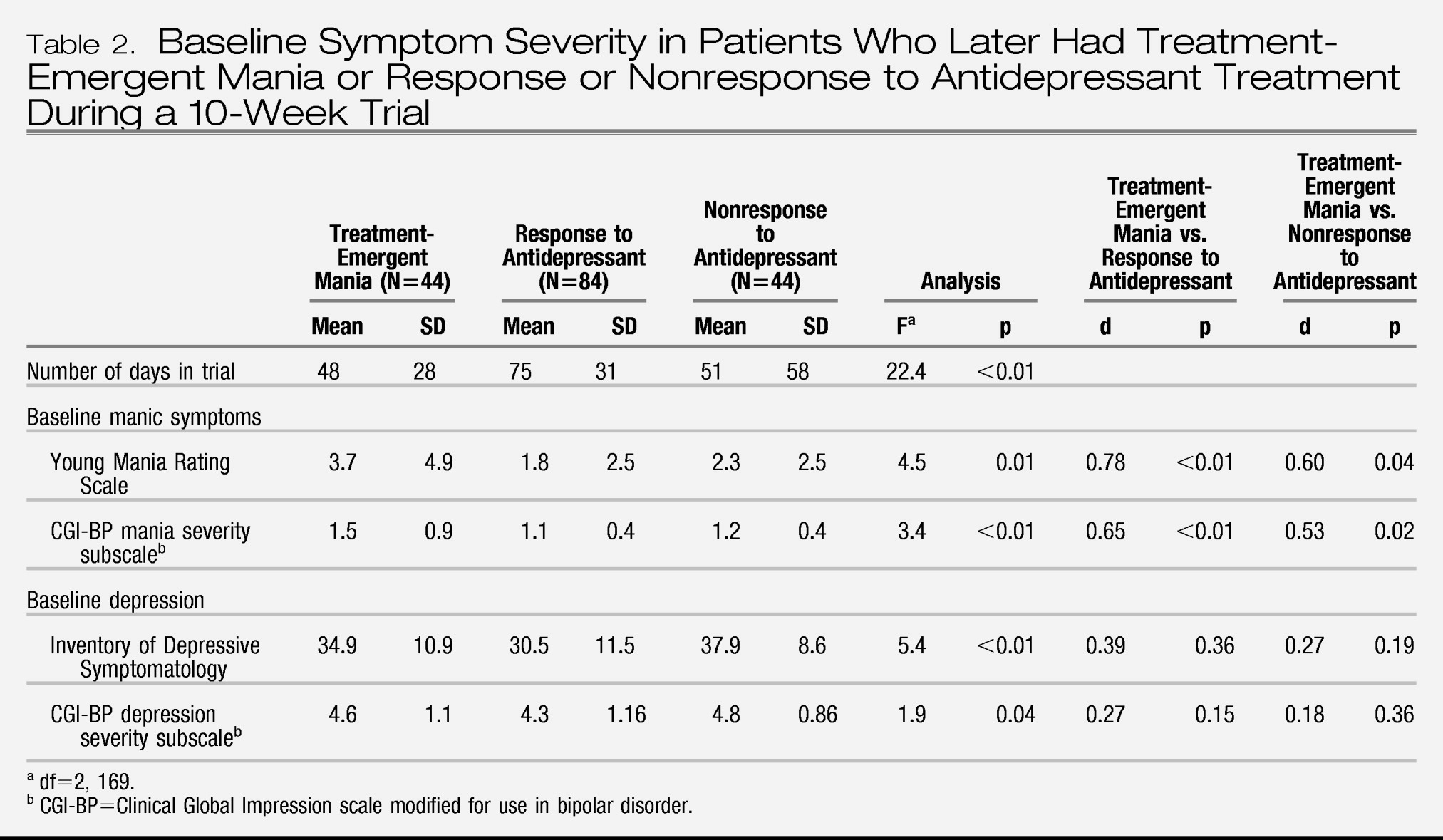

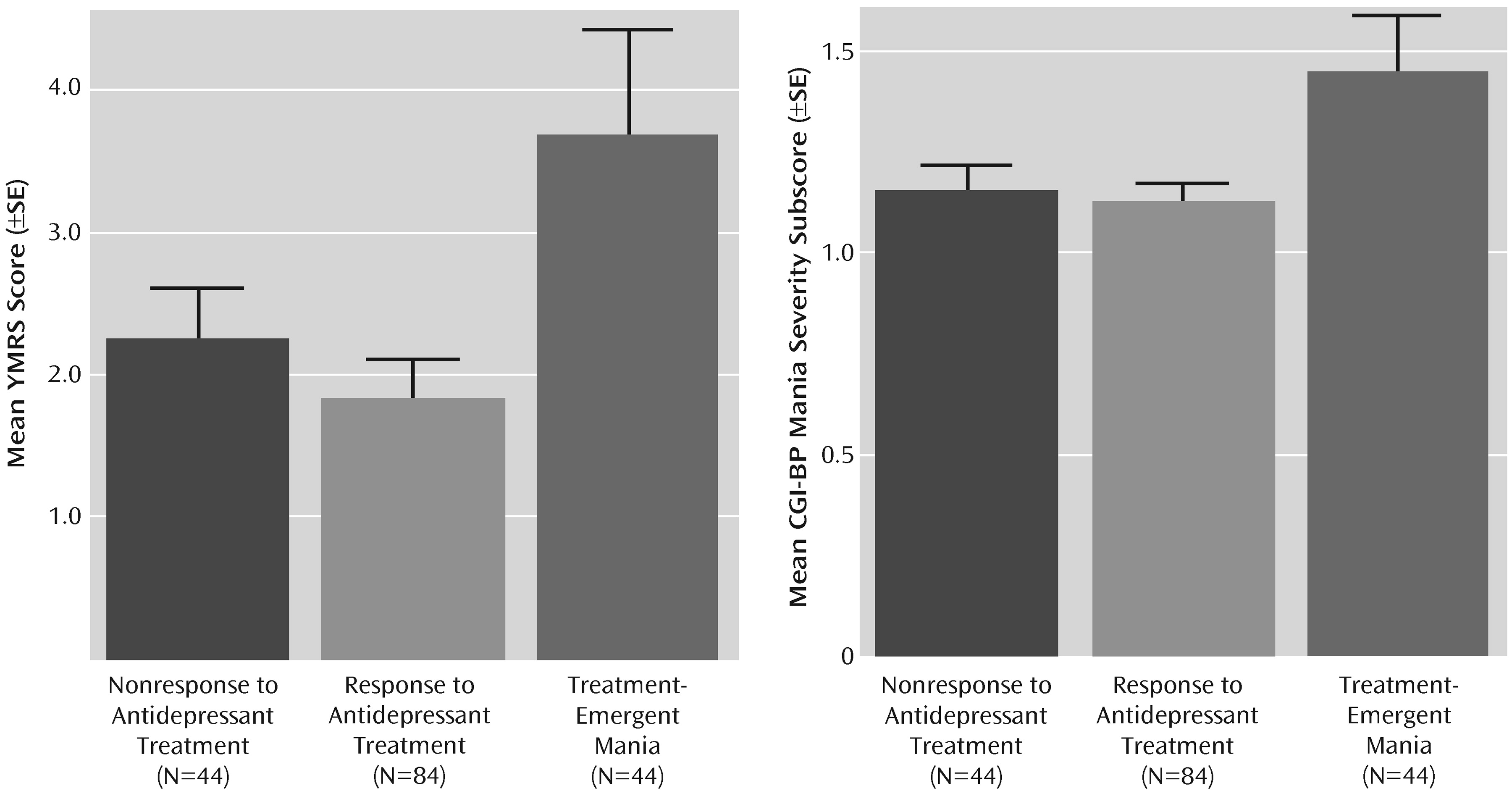

As shown in

Table 2, the mean number of days in the 10-week antidepressant trial was significantly lower in the group with treatment-emergent mania compared with the antidepressant nonresponse and response groups. Number of days in the trial was related to baseline manic symptoms; the severity of manic symptoms, as measured by both by YMRS score and CGI-BP mania severity score, was significantly higher in the group with treatment-emergent mania compared with the antidepressant nonresponse and response groups (

Figure 1). Baseline depressive symptoms, as measured by the Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology and the CGI-BP depression severity score, were significantly higher in the antidepressant nonresponse group compared with the treatment-emergent mania and antidepressant response groups.

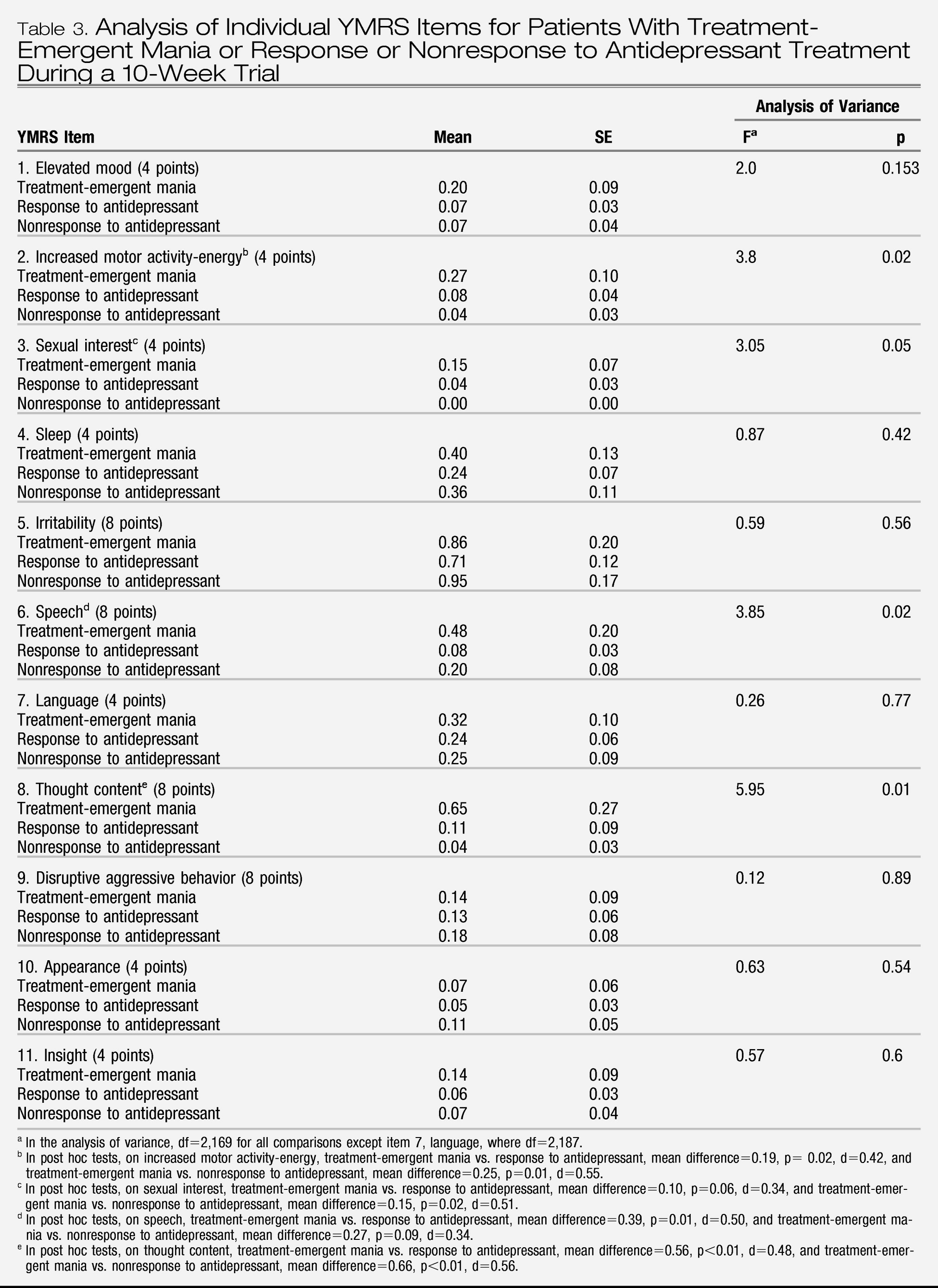

To further elucidate the relationship between YMRS items and treatment-emergent mania, analyses of variance and post hoc tests on items that showed group differences (treatment-emergent mania versus antidepressant nonresponse and treatment-emergent mania versus antidepressant response) were conducted. Scores on three YMRS items were significantly higher in the group with treatment-emergent mania: item 2, increased motor activity-energy; item 6, speech; and item 8, thought content (

Table 3). To verify that these results were not unduly biased by the slight non-normality of the YMRS scores (the distribution was skewed to the right because relatively few patients had high scores), we confirmed them using a generalized linear model based on a Poisson process (overall YMRS score: χ

2=39.36, df=2, p<0.001; item 2: χ

2=12.5, df=2, p<0.01; item 3: χ

2=9.5, df=2, p<0.01; item 6: χ

2=19.28, df=2, p<0.001; and item 8: χ

2=44.47, df=2, p<0.001).

To further explore the relationships between YMRS items and treatment-emergent mania, a maximum-likelihood factor analysis with varimax rotation of the YMRS item scores was used to identify clusters of items of YMRS that covaried. An analysis of variance based on the factor scores was then used to determine whether these facets of mania were also related to treatment-emergent mania. Based on the Kaiser criterion, we identified four factors of the YMRS: the motor/verbal activation factor was characterized by items 2, 6, and 7 (see

Table 3); the thought content/insight factor was characterized by items 8 and 11; the aggressivity factor was characterized by item 9; and the appearance factor was characterized by item 10. Items 1, 3, 4, and 5 did not load on any meaningful factor. Comparing groups on the basis of their factor scores showed that only motor/verbal activation was related to treatment-emergent mania (F=3.99, df=2, 169, p=0.02); all other factors showed no significant relationship.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first controlled study of antidepressant treatment in bipolar depression to suggest that the current phenomenological presentation (i.e., a confirmed DSM-IV episode of bipolar I or II depression with concurrent minimal manic symptoms) prior to the antidepressant treatment prescribed in the trial distinguishes the group of patients who develop treatment-emergent manic or hypomanic symptoms from those in either the antidepressant response or nonresponse group. Specifically, the co-occurrence of increased motor activity and speech predicted, in two different models, treatment-emergent manic or hypomanic symptoms. These two symptoms have also recently been shown to have the highest specificity and positive predictive value in distinguishing depressed bipolar outpatients with mixed episodes from those without (

41). In our study, thought disorder (such as distractibility and racing thoughts) was associated with treatment-emergent manic or hypomanic analysis of variance.

Our findings complement recent work from the STEP-BD program reported by Goldberg et al. (

42), who found that 3-month adjunctive antidepressant treatment not only did not speed time to recovery from an index episode of bipolar depression compared with no antidepressant treatment but also was associated with significant manic symptoms at study endpoint (

42). Goldberg and colleagues used a semistructured interview that assessed the number of manic symptoms in each categorical group (adjunctive antidepressants versus none). While they did not analyze treatment-emergent switch, our study and theirs highlight the finding that short-term use of antidepressants may have liabilities—induction of mania or hypomania or persistence of manic or hypomanic symptoms—in bipolar depressed patients who have minimal manic symptoms at baseline.

Unlike previous studies in which a number of clinical variables were linked to treatment-emergent mania, in this study we found no past clinical variable to be associated with treatment-emergent mania. These results are similar to those of a recent study by Carlson et al. (

43), who were unable to identify a clinical risk factor associated with antidepressant-associated switch from depression to mania; furthermore, the time to and the duration of any subsequent manic episode were not significantly different in seven patients who received antidepressant treatment compared with 10 patients who did not. Our study did not assess or have an adequate sample size to evaluate treatment-emergent mania and serotonin transporter genotype (

28,

29), hyperthymic temperament (

31), psychosis (

32), or mixed depressive symptoms (

17). A retrospective study by Bottlender et al. (

17) that found tricyclic antidepressant use and lack of mood stabilizers to be associated with the switch process, along with recent data suggesting that the presence of a current mixed episode increases the risk of future mixed episodes, particularly in women (

44), suggests that phenomenological presentation, longitudinal course of illness, and treatment selection may have important interactions that may resolve some of the controversy surrounding antidepressant-induced mania.

Our study results are limited by the modest effect size and lack of a placebo control. The lack of a structured diagnostic assessment at the time of manic switch is also a limitation, although it is standard in the field to confirm diagnosis at study entry, prior to randomization, and to use a symptom severity scale, such as the YMRS or CGI, as an outcome measure of switch. The mood stabilization regimen and, to a lesser degree, the type of antidepressant treatment (more than 90% of our subjects in this study were also participants in our comparative study of sertraline, bupropion, and venlafaxine (

10)) were not standardized in this study; larger studies with standardized treatment would provide more information. It is clear from previous work that mood stabilizers reduce the risk of switch (

33), but there has been no comparative study of antidepressant switch prevention with differential mood stabilization treatment (i.e., lithium, valproate, carbamazepine, lamotrigine, or an atypical antipsychotic). Furthermore, this study is unable to answer the question of whether antidepressant treatment raises the risk of switch or not. The recent controlled data of STEP-BD would suggest that adjunctive antidepressants (paroxetine or bupropion) were no more likely than placebo to be associated with a switch from depression to mania or hypomania (

6).

While not confirmed by structured diagnostic assessments, the three distinct YMRS items identified in our study (psychomotor activation, pressured speech, and language/thought disorder) may be a surrogate marker for a depressive mixed state. Depressive mixed state is not operationalized in DSM-IV or ICD-10, but there is increasing recognition of its presentation and clinical characteristics (

41,

42,

45).

Several definitions of mixed depression have been proposed (

45–

48). In general, it is considered a syndromal episode of major depression plus several symptoms of mania or hypomania. Mixed depression as defined by manic or hypomanic symptoms (

41) occurring within a major depression is thus distinct from the traditional mixed episode, consisting of major depression plus four manic/mixed symptoms. This distinction is relevant because currently a full mixed episode is categorically classified as a manic episode subtype; in contrast, a mixed depression, while not yet fully operationalized, is conceptualized as a depressive episode. Further discussion of the categorical versus dimensional aspects of mixed symptoms may prove to be valuable in DSM-V and ICD-11 committee work.

Future research should focus on the pattern of manic symptoms in syndromal depression that is associated with treatment-emergent mania in both clinical and nonclinical samples. Furthermore, it is unclear whether this is a phenomenon unique to bipolar depression with minimal manic symptoms; while mixed symptoms are more common in bipolar than in unipolar disorder (

45), treatment-emergent mania is always reported as an adverse event in unipolar depression clinical trials. It would be valuable to reanalyze clinical trials of antidepressants in both bipolar and unipolar depression in which the YMRS was used as an outcome measure or for adverse event monitoring to establish the generalizability of this clinical phenomenon. Recent controlled monotherapy studies would suggest that the placebo switch rate, or course of illness switch rate, is 5%–10% (

6,

14); the placebo arms of these clinical trials may also shed light on whether the natural course of illness switch is also related to a baseline mixed depression presentation. It would be valuable to reassess these switch rates based on the presence or absence of mixed symptoms.

A careful examination for these specific symptoms of mania is warranted prior to antidepressant treatment for patients with bipolar depression. When considering adjunctive antidepressant treatment with unimodal antidepressants for bipolar depression, the risk of treatment-emergent mania or hypomania should be carefully weighed against the potential benefit of the antidepressant medication. In addition to type of antidepressant prescribed, our data suggest that the presence of manic symptoms in syndromal depression may be associated with a poor clinical outcome. The optimal treatment of mixed depression remains to be delineated.