Although researchers and clinicians are in agreement that agitation is a serious problem in persons with Alzheimer's disease (AD), estimates of the prevalence of agitation, especially in AD, differ greatly. Recent estimates include those of Reisberg et al.,

1 who found symptoms of agitation in 48% of the medical charts they reviewed from outpatients with probable AD. Devanand et al.

2 reported that 55% of the 106 outpatients with probable AD they studied exhibited motor agitation. Levy et al.

3 found agitation in 28% to 32% of 181 outpatients with probable AD; Mega et al.

4 reported that symptoms of agitation were observed in 60% of the 50 persons with probable AD in their study, and Devanand et al.

5 found “behavioral disturbance” in 51.9%, but “wandering or agitation” in 38.7% of their sample of 235 subjects with probable AD. Most recently, Lyketsos et al.

6 reported that 22% of 214 persons from the community with probable AD exhibited symptoms of agitation, whereas Haupt et al.

7 found agitation in 88% of outpatients with probable AD seen in their clinic.

Although agitation is only one type of behavioral disturbance, the symptoms typically associated with agitation by one author or instrument may be classified more or less specifically by another. An example is provided by the comparison of the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI)

10 and the Behavior Rating Scale for Dementia (BRSD),

11 where restlessness, uncooperativeness, and verbal aggression are all considered symptoms of agitation on the CMAI but are elements of subscores representing irritability/aggression, behavioral dysregulation, and inertia, respectively, on the BRSD. Although we use the terms “agitation” and “behavioral disturbance” somewhat interchangeably, our analyses are focused on clinically important behavioral disturbance that excludes, to the extent possible, significant psychopathology (e.g., delusions, depression, hallucinations) and which may comprise disruptive symptoms that are essentially unrelated to each other.

In spite of sometimes dramatic prevalence rates, the rate of medication prescriptions for the treatment of agitation or behavioral symptoms is quite low—less than 20% in all of the studies cited above in which this information was provided. It may therefore be the case that prevalence of agitation has been determined in a way that overstates (or understates) its true clinical impact. In this study we sought to define “normal” levels of behavioral symptomatology, in order to evaluate various estimates of the prevalence of agitation in persons with probable AD. By establishing a normal range for these behavioral symptoms, we hoped to 1) derive an estimate of their prevalence in AD that closely represents the subpopulation most likely to be treated or to seek intervention; and 2) establish criteria such that persons with AD who exhibit behavioral symptoms below this threshold will not be considered “agitated.”

RESULTS

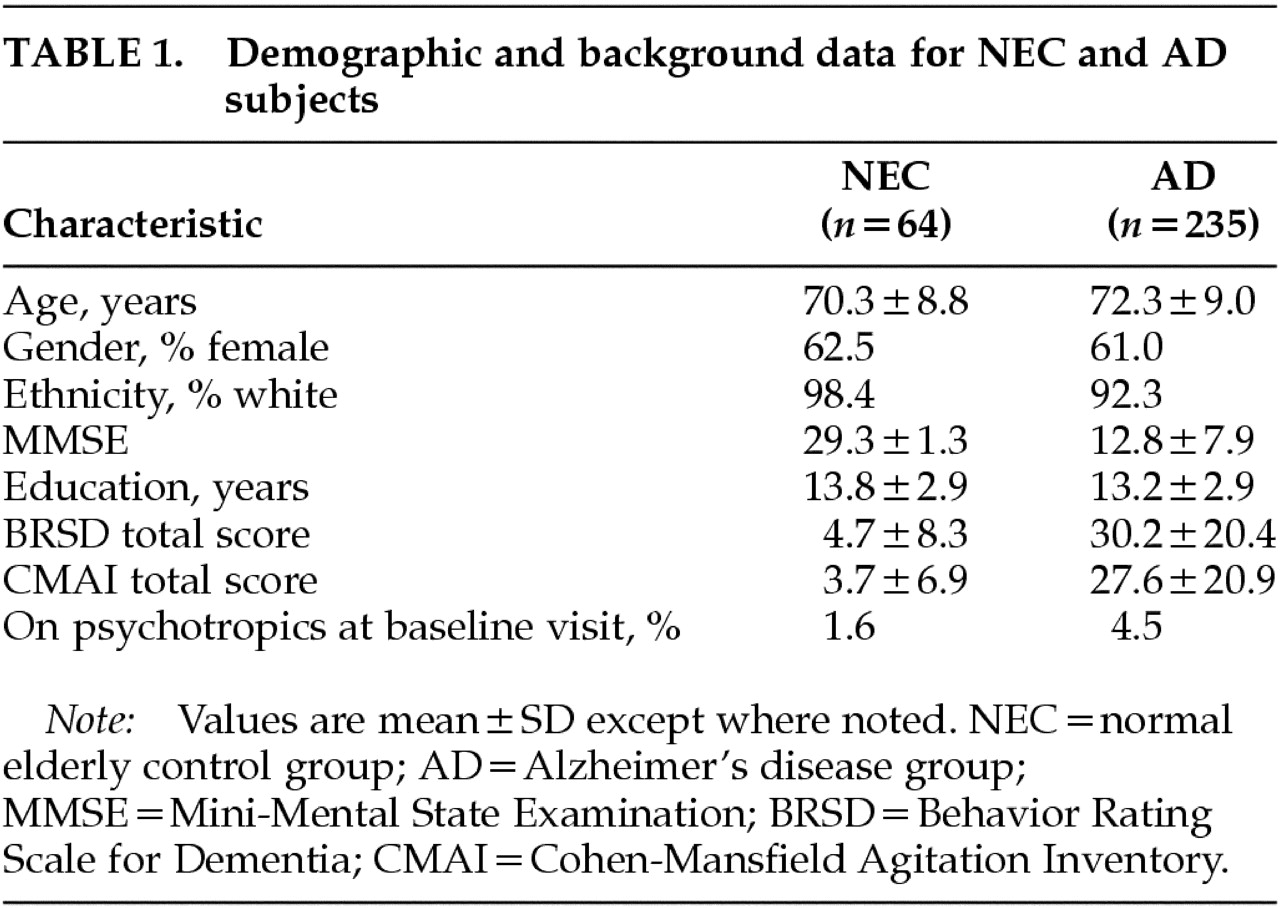

Under the ultraliberal criterion (any person with a CMAI score>0 was considered “agitated”), 56.2% of NEC were classified as “agitated,” compared with 99.1% of AD (all but 2 patients). One NEC had been prescribed a psychotropic at screening (imipramine, for bladder control); 18.2% of patients with AD having CMAI scores>0 had been prescribed psychotropics at screening.

The highest CMAI total score at baseline for a person in the NEC group was 48; however, the rest (98.4% of this group) scored at or below 14. Because of the wide difference between this NEC subject and the rest of the NEC cohort, the individual with the score of 48 was considered an outlier and was excluded from group comparisons. Therefore, we took CMAI=14 to be the cutoff score under the liberal criterion, so that any person with a CMAI total score ≥15 was considered “agitated.” Only 1 NEC (1.6% of this group), with the outlying CMAI score, would have qualified as “agitated” under this liberal criterion.

Under the liberal criterion, 68.2% of AD qualified as “agitated”; of these, 22.1% had been prescribed psychotropics at screening. Of the individuals with AD whose CMAI total scores were below the liberal cutoff (i.e., CMAI≤14), 9.6% (7 individuals with a total of 8 prescriptions) had also been prescribed psychotropics.

The conservative criterion, endorsement (frequency rating of 1 or more days in past month) of the single item “agitation” from the BRSD, resulted in 66.7% of AD patients being classified as “agitated.” This percentile was applied to the frequency listing of CMAI total scores for the AD patients and corresponded to a CMAI cutoff of 14, the same score as was identified by the “liberal” criterion.

Table 2 presents the results of the three criteria in terms of CMAI total score cutoff, prevalence estimate, specificity (with respect to NEC), and psychotropic prescription rates.

When we examined the proportion of NEC who endorsed item 19 from the BRSD, we found that 29.7% of NEC would have been classified as “agitated” if we had used item 19 by itself to estimate prevalence of agitation in NEC subjects (rather than using its endorsement to generate a prevalence estimate–derived CMAI score cutoff). When we applied the 66.7 percentile derived from the BRSD item-19 endorsement to the CMAI total scores, we found that one NEC subject (1.6%) would have been classified as “agitated,” the single NEC subject with the CMAI score of 48.

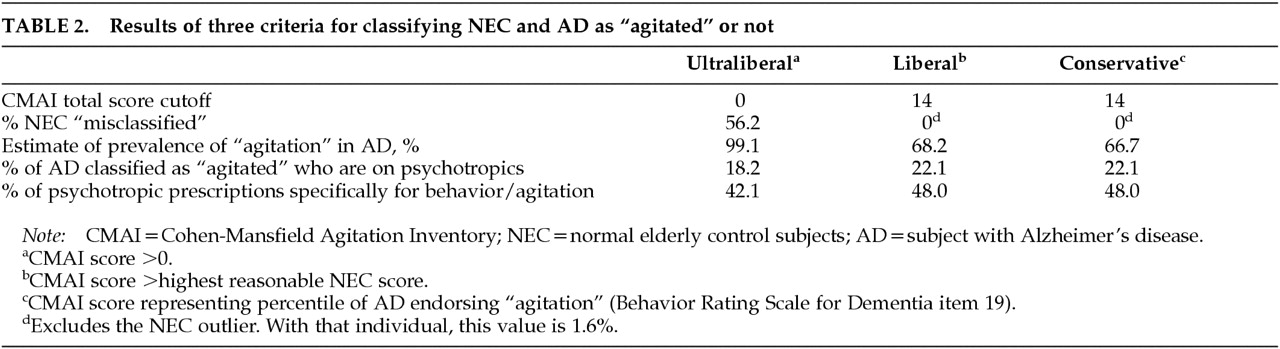

Among the 160 persons with AD whose CMAI total scores were characterized as representing excessive disturbance under the “liberal” and “conservative” definitions (i.e., ≥15), 48% of 50 psychotropic prescriptions were for behavioral disturbance, 28% were for sleeplessness, insomnia, or night restlessness; 22% were for anxiety or depressive symptoms; and 2% (n=1) were for other reasons (memory problems). Among persons with AD not classified as behaviorally disturbed (i.e., CMAI≤14), 6 of 7 psychotropic prescriptions were for depressive symptoms and sleep-related disturbances (3 prescriptions for each symptom); the remaining one was for nausea.

Psychotropic medications and their indications, reported at baseline by knowledgeable informants, for disturbed/nondisturbed persons with AD under the liberal and conservative criteria are listed in

Table 3.

Under the ultraliberal criterion, 42% of the 57 psychotropic prescriptions were specifically for behavioral disturbance; the seven prescriptions described above for individuals with CMAI scores ≤14 apply to individuals classified as “agitated” under this criterion.

Chi-square tests showed that none of the three criteria resulted in differential rates of classification of men and women with AD as “agitated” (conservative: men, 60.9%; women, 70.4%; χ

2=2.3, not significant; liberal: men, 97.8%; women, 100%; χ

2=3.1, not significant; ultraliberal: men, 64.1%; women, 70.9%; χ

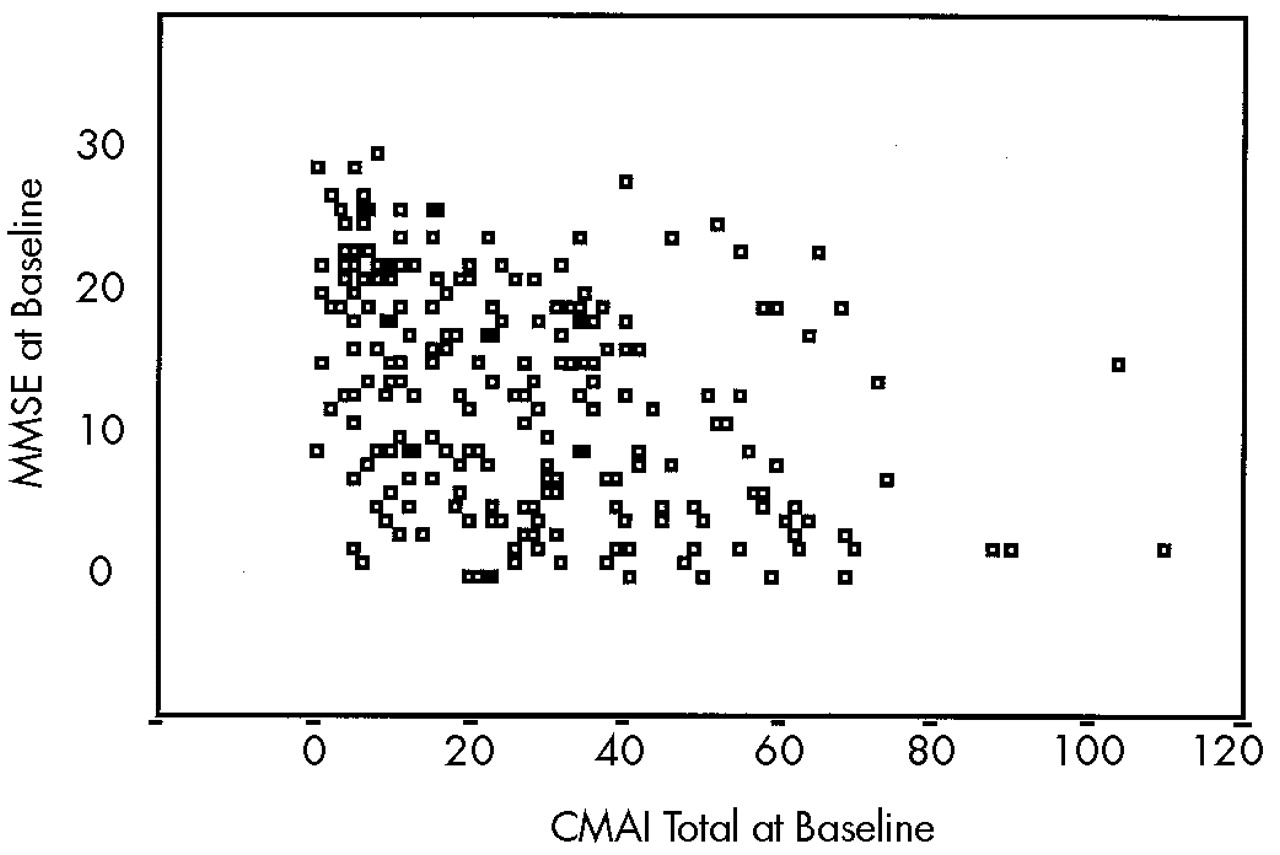

2=1.9, not significant). Although Mann-Whitney testing indicated that individuals classified as agitated by the “liberal” and “conservative” criteria had significantly lower MMSE scores (

Z=–5.3,

P<0.001),

Figure 1 suggests that individuals with MMSE scores across its range (0–30) fall into both agitated and nonagitated categories.

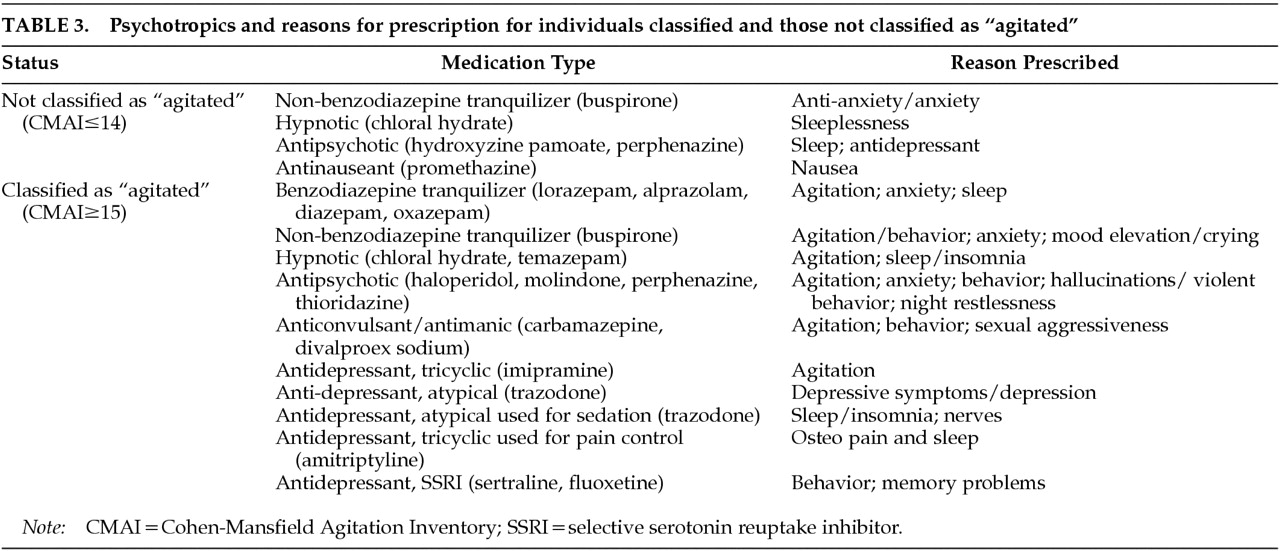

To compare the symptomatology exhibited by all NEC (except the outlier) and those persons with AD whose CMAI scores were 14 or less (i.e., not disturbed), we compared the rates of endorsement, as defined above, on the CMAI items. The comparisons of endorsement rates on only 8 of the 36 items had pre–Holm adjustment P-valued less than 0.05. More persons with AD than NEC endorsed 5 of these 8 items: repetitiveness, restlessness, pacing, handling things inappropriately, and temper outbursts (items 1, 14, 15, 19, and 24). The other 3 of these 8 items were endorsed by more NEC than persons with AD: verbally threatening or insulting, verbally bossy or pushy, and physical sexual advances (items 9, 11, 13). After Holm adjustment of the P-values, only one difference in endorsement rates, AD>NEC on repetitiveness (item 1), remained significant (data not shown).

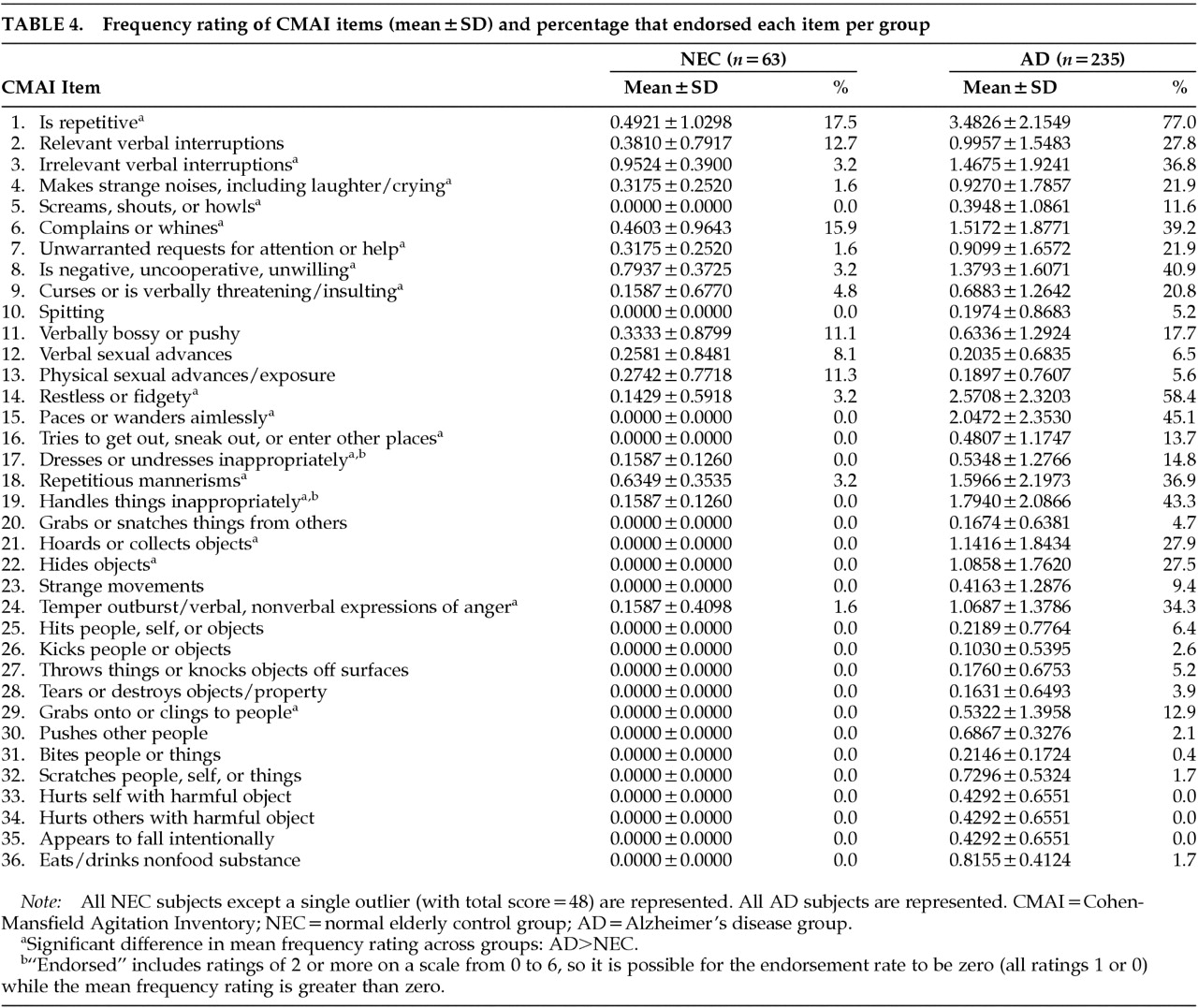

We then compared the mean frequency ratings for each item across the study groups (all AD vs. NEC) and calculated the endorsement rates in each group, for descriptive purposes.

Table 4 contains the mean frequency ratings, as well as the endorsement rates, per item for the NEC (except the single high-scoring outlier subject) and the entire AD group.

When we considered the entire sample of community-dwelling persons with AD, roughly 67.5% of whom we could classify as “behaviorally disturbed,” we found that frequency ratings were significantly higher for AD than for NEC for half of the 36 items: repetitiveness; irrelevant verbal interruptions; strange noises; screaming, shouting or howling; complaining; unwarranted requests for attention; uncooperativeness; verbal threatening/insulting; restlessness; pacing; trying to get outside; inappropriate dressing/undressing; repetitious mannerisms; inappropriate handling of objects; hoarding; hiding; temper outbursts; and grabbing/clinging to people (items 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 21, 22, 24, and 29; all Holm-adjusted P-values<0.05).

One of the 36 symptoms of agitation (repetitiveness) was rated by 17.5% of these NEC as occurring at least once or twice per week; more than 5% of this sample endorsed 6 of 36 items: repetitiveness, relevant verbal interruptions, complaining, verbal bossiness, and verbal and physical sexual advances (items 1, 2, 6, 11, 12, and 13).

DISCUSSION

Limitations of this study include the relatively high level of education of the participants and the relatively low percentage of minority representation. The very low level of behavioral disturbance, in general, in the patient population made this group ideal for investigating the lower limit of the range of agitated behaviors in AD.

Two independent criteria for classifying individuals as behaviorally disturbed were found to correspond to a CMAI total score of 15 or higher; we therefore conclude that for community-dwelling individuals with AD, CMAI total scores of 14 or lower should not be considered to fall into the behaviorally disturbed range.

Practically speaking, individuals with CMAI scores of 14 or less would not be good candidates for clinical studies of behavioral symptoms (and/or their treatment), although such individuals would be ideal subjects in clinical studies that monitor the emergence of new symptoms. Both a “conservative” and a “liberal” approach to defining “excessive” agitation resulted in the same CMAI total score cutoff, 14 points. When we compared persons with AD classified as “not disturbed” under this criterion against NEC in terms of the presence of symptoms of agitation that were endorsed, we found that a significantly greater proportion of persons with AD than NEC endorsed only 1 of 36 items. This suggests that persons with AD classified under this criterion as “not disturbed” are not different from normal control subjects in their behavioral symptomatology, and that excessive agitation is not present in this subsample of persons with AD.

Based on the results of these two approaches to classifying individuals as “behaviorally disturbed” or “agitated” (using the highest reasonable NEC score and using endorsement of BRSD item 19), we conclude that the prevalence rate of agitation in community-dwelling persons with AD is approximately 67.5%. This value is most consistent with the findings of Mega et al.,

4 is least consistent with the most recent estimates (22%;

6 88%

7), and is considerably higher than the prevalence estimate of 44% for global agitation

22 that represented the median across earlier studies.

Although the ultraliberal definition of agitation may have been highly sensitive, labeling all but two AD patients as “agitated” (99%), it had an unacceptable level of specificity, resulting in more than 56% of normal control subjects being classified as “agitated”; the ultraliberal prevalence figure may be unacceptably high given earlier published estimates. By contrast, the conservative and liberal criteria resulted in estimates of 66.7% and 68.2% (average: 67.5%) for the prevalence of behavioral disturbance in these AD patients, with very high specificity; only the NEC outlier would have been classified as “agitated.”

Psychotropics were prescribed in 18.2% of those individuals with AD who were classified by the ultraliberal criterion as having “excessive” levels of behavioral symptoms; this was slightly less than the rate in those classified as excessively disturbed under the liberal definition (22.1%). Additionally, 42.1% of psychotropic prescriptions in those classified as agitated under the ultraliberal criterion were specifically for behavioral symptoms, whereas under the liberal criterion, 48.0% of those psychotropics prescribed to AD patients who had agitation were specifically for behavioral symptoms.

The prescription rates (18% and 22%) are roughly comparable to those reported previously for populations of community-dwelling persons with AD. Much higher psychotropic prescription rates were reported by Reisberg et al.,

1 who found that 47.4% of 57 AD patients were being treated with thioridazine in their cross-sectional chart study, and by Haupt et al.,

7 who found 42% of 77 AD outpatients had neuroleptic prescriptions for motor disturbances at any time over 2 years. A much lower rate was observed by Levy et al.

3: only 9.4% of 181 AD patients initiated psychotropic medication during a 1-year period. Devanand et al.

2 reported that 27.6% of 106 AD patients were on psychotropic medications at first evaluation, and later, Devanand and co-workers

5 reported that 14.0% of their 235 subjects had prescriptions for psychotropic medications at the baseline visit.

We also found that 18 of the 36 symptoms on the CMAI may be the most descriptive for community-dwelling persons with AD in general, as compared with NEC: repetitiveness; irrelevant verbal interruptions; strange noises; screaming, shouting or howling; complaining; unwarranted requests for attention; uncooperativeness; verbal threatening/insulting; restlessness; pacing; trying to get outside; inappropriate dressing/undressing; repetitious mannerisms; inappropriate handling of objects; hoarding; hiding; temper outbursts; and grabbing/clinging to people. In an earlier study, we found that 10 of 36 CMAI items distinguish between persons with AD who had greater and lesser degrees of agitation;

9 all but one of these 10 items (verbally bossy or pushy) were among the 18 items that distinguish persons with AD from NEC. Thus, it may be possible to monitor the agitation of community-dwelling persons with AD using a subset of CMAI items that is most descriptive of this population in particular, as opposed to nondemented elders or persons in nursing homes.

Toward this end, we are currently examining the emergence of the behavioral symptoms included in the CMAI. We plan to use the CMAI total score cutoff of 14 to determine if there are items that are more likely to emerge given higher initial CMAI scores, or if more emergence can be expected in community-dwelling persons with AD who have higher or lower initial total scores.